How does a book come into the world?

First of all, the book was born out of love for the format, for the intimacy that a book creates. But if I think about it in depth, it began back when I was studying at the Bezalel Academy of Art in the early 2000s. I really liked rummaging in the big library, and at the same time I would go to Dizengoff Center, to the terrific fashion magazine stand there. I was obsessed with the narrative that happens when turning pages. I was very preoccupied with how to combine my love for different types of photography. As a kind of small rebellion against the academy, in my first year I shot only with a pocket Olympus Mju camera. There are no decisions about exposure with point and shoot cameras; you can’t change lenses. At most you can decide whether or not to use the flash.

A rebellion against the large, “artistic” format?

Yes, and perhaps also a bit of an escape from decision making. Shooting with a pocket camera was still considered “inferior.” When I graduated in 2004, negatives still dominated, though most people scanned and printed digitally. There were very few who were working with the first digital cameras, which were 8 megapixels and considered “inadequate.” The first project I remember that was shot with a digital camera was “Radius 500 meters” by Sharon Yaari in 2006. It was a project that Yaari photographed in the vicinity of his home in Tel Aviv, and it was very meaningful for me. I know many photography teachers who still assign their students his “500 meter exercise.” Now, with the coronavirus (and the lockdowns) we have all tried our hand at this exercise. I often try to imitate things I recognize in other photographers.

For years I had on a wall in my home Jim Jarmusch’s text on originality, which ends with the famous quote from Jean-Luc Goddard: “It is not where you take things from, it is where you take them to.” Do you too “take things from place to place”?

Completely. I can even find myself looking for a place I saw in a photograph, and trying to understand the angle the photographer I want to “take from” shot it. Almost at the level of a stalker. This always leads to different results than I imagined. I also copy the format. Every camera has a history of how it was used, even the rolls of film.

Exactly. I shoot with Kodak Tri 400-X 35mm film because of Robert Frank. Can you give us some examples?

A lot. If, for example, I want to imitate the slow and measured photography of Stephan Shore or one of the “New Topographer” photographers, Robert Adams or Nicholas Nixon, I will take a 6x7 medium format camera where the number of frames in a single roll of film drops to 10, as opposed to a regular roll of film that contains 36 frames. With large format, you shoot one plate at a time; the work becomes a much slower and more calculated process because of the cumbersomeness of the camera, and also the cost.

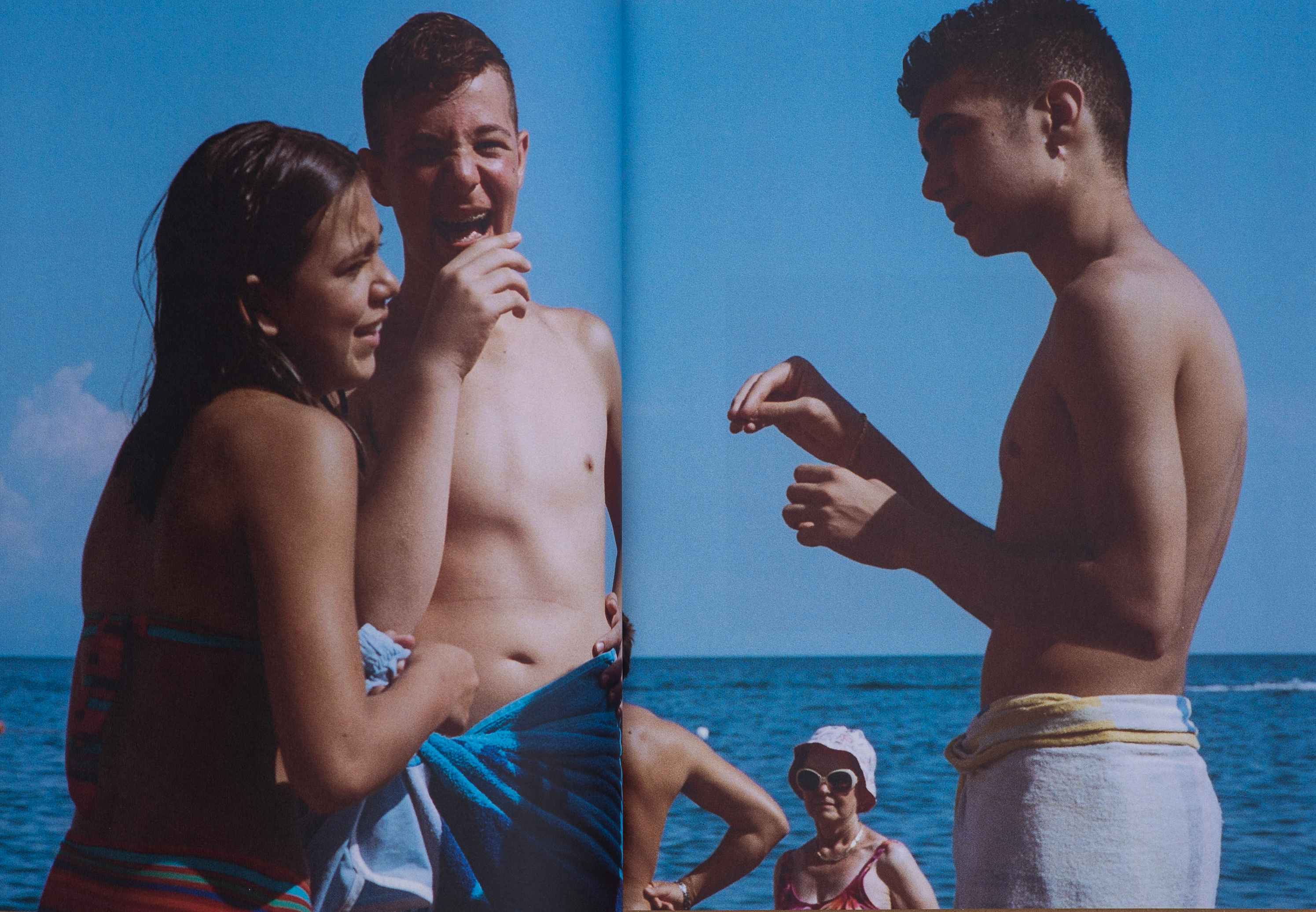

On the other hand, I connect to an Americana trash aesthetic like in the early book Son Of Bob by Terry Richardson, before he became famous as a fashion photographer and later (infamous) for serial sexual harassment. This forces me to shoot with a pocket camera or flash. The desire to photograph like William Eggelstone or Robert Frank led me to buy my first rangefinder camera, a Voightlander, which was regarded as a backup camera for those photographing with a Leica. The idea is that when there is no mirror there is less noise, and the camera is less intimidating. For me, shooting with a rangefinder is an attempt to produce an intimate photograph in an urban space. Here too I feel that I fit into a long tradition of street photography starting with Henri Cartier Bresson, through Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Bruce Gilden.

Video curtesy of Books Leafing

Course led by Adi Branda at the HIT School

When did you feel that things became “yours”?

In my fourth year I took a course with Yigal Shem-Tov. It was a one-on-one course, and at the end I presented an exhibition. Back then you would print relatively large contact sheets, and I played with them in a white sketchbook. I tried to translate the playfulness created in it onto the wall, into a sequence that takes you on a journey. It created a new language I felt was mine. Yossi Berger reviewed that exhibition, I’ll look for the Mini DV for you. I’m still scared to watch it.

After my studies, I started working in the studio of Goli Cohen who was one of the top fashion photographers at the time. The illusion of the glitter was quickly shattered for me, and I realized that I had to go back to school and I enrolled in Bezalel for an MFA. Around the same time, I had started going to a psychodrama therapist who insisted I get a professional diagnosis for my attention disorders. I always knew I had it, but in high school they called it dyslexia, and I only got five minutes extra on tests. I had a hard time in school. This therapist claimed that my need for advanced degrees was related to my need to prove that I wasn’t stupid.

Reproduction by Igal Felix

I went through a process with her of learning to find ways to work and to create a sense of continuity for myself. I started by using keywords for the things I photograph. One of the things that gave me “legitimacy” to work like this was an exhibition by Wolfgang Tillmans called If One Thing Matters, Everything Matters. Someone from class had brought in the exhibition catalogue. The book is built from thumbnails of works I knew from the late 1990s. The interesting discovery was a note in the back of the catalogue, in which Tillmans wrote the topics that preoccupy him. There was a kind of order to this whole photographic array. It was then that I began to understand how I actually operate.

This is an appropriate place to refer to the exhibition catalogue Lonely Planet (Ashdod Museum, 2021) curated by Anna Yam that you are currently participating in, along with five other photographers who deal with wandering and movement in the world. The catalogue consists of conversations about photography. Anna starts by reading a list of subject files from your computer. I’ll read examples from the catalogue: “Sculpture” “Tough,” “Just What I Need Right Now,” “Agrobank,” “Shapira,” “Pecan,” “Chairs,” “Grandmas,” “Climbing Plants,” “Palms,” “The International.” What can I say, it’s just what I need right now.

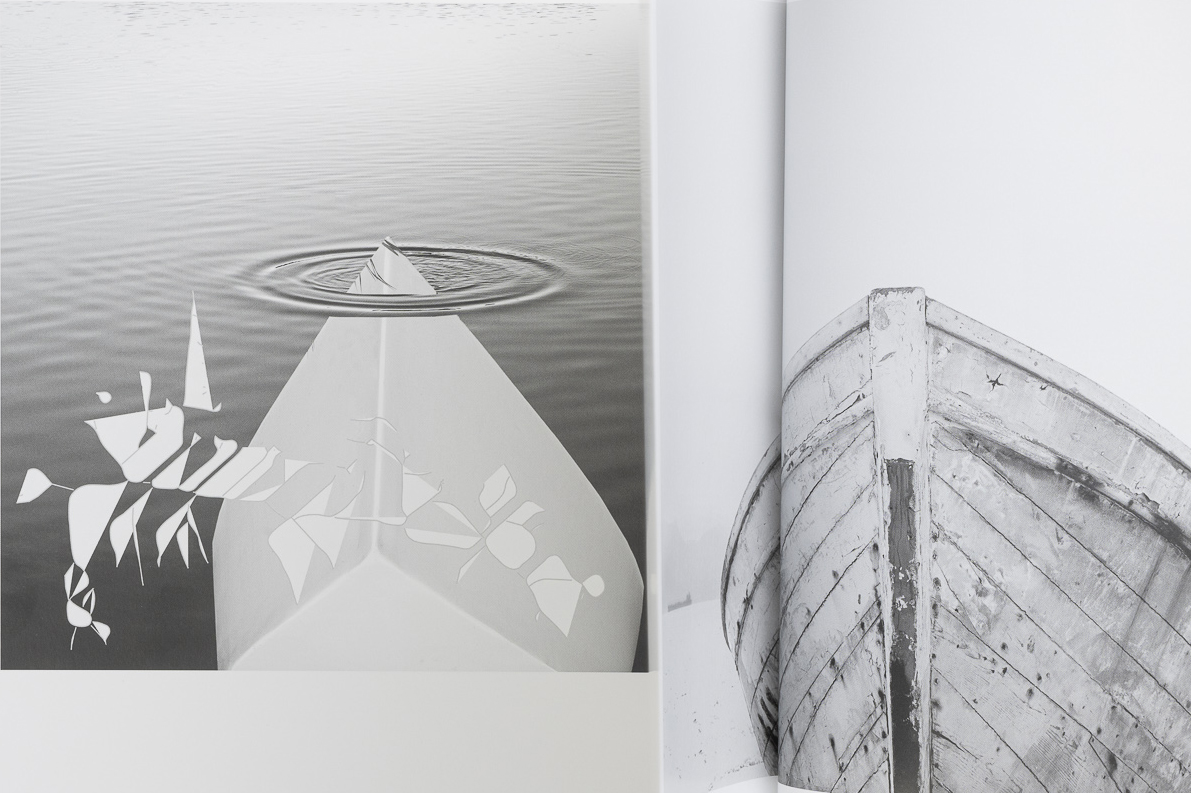

LOL. I will explain. For example, palms. I began to recognize that I had already photographed a palm tree with leaves that fall in a certain way, and then I researched and understood that there is a beetle that damages palm trees called the “red palm weevil.” So it became a subject. If I go back to the sequences I started creating, the files make it easy to pull out images. In the book I tried to produce a “broken” leafing, just as I produce “broken” sequences in the exhibition.

From the exhibition, If One Thing Matters, Everything Matters

You deal visually with the idea of the “patch.” The patch is meant to repair a hole in a garment, For example, it’s something that is sewn in when there’s no other choice, but it has the potential to completely change the meaning of the thing it is being added to. One might say that even in the editing of the book you used “patches,” whether in the form of differently sized “inserts,” or accordion fold-outs of series that open from the main sequence of the book. You also deal with the way in which aesthetic, textile, and architectural elements find themselves “glued,” transferred from place to place, in differing degrees of elegance.

The “patch” is interesting in the sense of a botched attempt to fix something. It’s funny that it’s also the name of a tool in Photoshop for correcting areas in an image, a tool that allows you to sample a certain area from another area. That’s a bit of what my eye looks for in photography, to take an element that I saw in Ashdod, let’s say, and that I then saw again in a neighborhood in Jerusalem. By the way, this reminds me of the name of the book—Dust & Scratches—which is also taken from a Photoshop tool. This is the name of the exhibition curated by Noga Davidson in 2017 that led to the book. Two months before the exhibition, we had agreed on 12 frames. Noga understood that I longed for my own book and suggested that in the time left until the opening, I make a book out of everything that was not included in the exhibition. That’s how the first version came to be created with a cardboard cover and “reference copy” sticker.

The name of the book is like a secret. Can you tell us how you got there?

One day I got caught up in a technical “guy’s” conversation about photography. Someone talked about a place where you scan and later apply an automatic filter in Photoshop called “dust & scratches.” It was a kind of a derisive poke at the photo not being airbrushed manually, as it should be. The poetics of the name stuck with me.

So what happened between 2017 and 2021?

I bound the first prototype of the book with the bookbinder, and presented it at the exhibition. Then I made a second version with a cover design by Racheli Kinorot, which I submitted to the competition of the photography book fair in Kassel in the unproduced books category (The Kassel Dummy Awards). It was shortlisted, so I went there to meet with the judges to get some feedback. One of them was Pierre Bessard, who has an independent publishing house for small edition photography books. That same year I applied to the Israel Lottery for Culture & the Arts, and I managed to raise a sufficient amount for printing, which was how the third and final version was created. There are several dozen copies for sale in Israel, the copies of the first edition in Europe is sold out. The publisher told me that today actually.

Wow! Amazing. What was it like to work with a French publishing house? What did you learn?

The designer Thibault Geoffray completely reduced all the white pages and made the edited version much more compact. He kept my inserts, and even added two of his own. Most of the books published by Pierre have a very tactile cover that makes you immediately want to hold them, he introduced the fabric and the shiny foil that he claims refers to the combination of color and black and white photographs that are in the book.

When the book came out in the summer of 2021, I traveled with Pierre’s publishing house to the photography festival in the city of Arles (Les Rencontres D'arles). What’s cute there is how everyone signs each other’s books. In Israel we are embarrassed by this, why would I ask someone for a signature? There everyone thinks for a few moments, writes dedications, small haiku poems. Students come for example, and the teachers sign a copy. It’s wonderful. By the way, at the festival they sold a reissue of an old book by Michael Schmidt, a photographer I discovered relatively late, who photographed mainly in East Germany in the 70s and 80s. They sold the book for 50 Euros, but when I went to buy it, the seller said there was also a copy of the first edition for sale for 700 Euros. I said “no thanks,” but it was really a glimpse into the world of books abroad.

Why are there no texts in the book?

I feel like the book is self-explanatory. For me, it’s also connected to the fact that today as a photographer I build the context of my work. When I finished my studies I wanted a gallery to take me on and make me an artist. Today, being part of the Indie Gallery (a cooperative photography gallery), I am responsible for creating the context of my work: with the gallery members, whoever I meet with, in the hope that the work will succeed in breaking through the boundaries of the specific context within which it was created. This is a very big challenge for art today, of any kind.

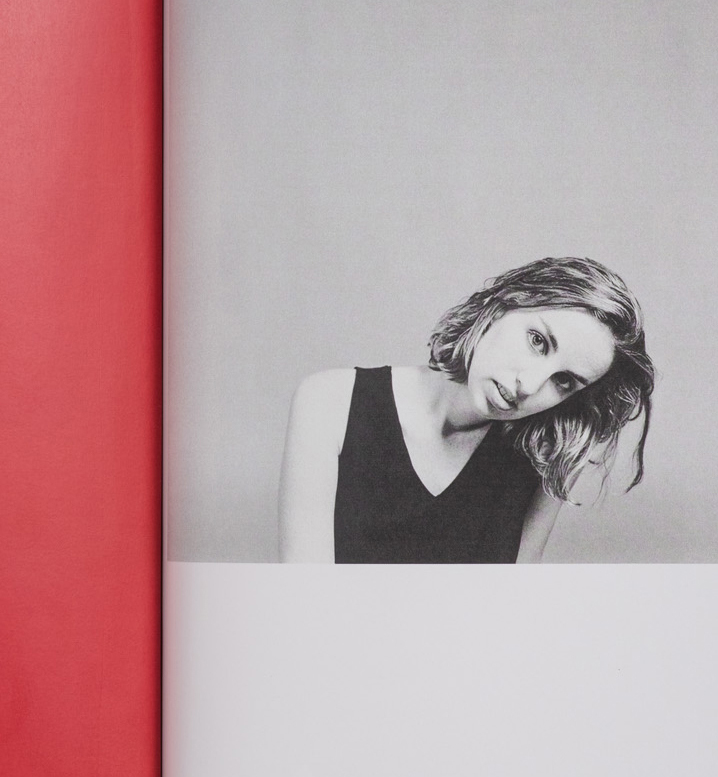

In the book, you combine typological series, then something that looks like a photograph of an American landscape, suddenly a family photo taken with flash, then a studio photo that looks like a fashion shoot. What do you think about the fact that the world of fashion and the world of conceptual art photography in Israel are still largely separate?

I’d like to hope that maybe this is finally changing here. I consciously try to challenge these hierarchies. Speaking of flash, which is seemingly associated with the world of fashion or PR photography, for me flash is an artistic action. For instance, when you experience a flower pot, and want to take a picture of it, you throw a flash on it. Essentially energy is thrown at the object that comes back to you. The flash is some kind of explosion between you and the thing you are photographing. It’s a kind of imprint of your gaze on the object.

Regarding what you’re saying, I’m thinking of Jürgen Teller and Tillmans, who do commercial work and at the same time art photography. I remember Teller’s book Go Sees from the Bezalel library, I remember being surprised that it was there. It’s a book that consists of photos of agency models who came to be photographed by him in a kind of audition, like quick look-books. He photographed in staircases, near a doorway or outside the studio. There is something in these photographs that’s so human, self-conscious, without makeup, mundane. I totally connect with this way of thinking.

Making a book is like…

If I compare it to the world of music, then it’s like making an album. In one of the conversations with my brother, who is a musician, we talked about the fact that today it’s possible to produce any kind of effects. So for example, you can use a keyboard and make it sound like a Fender Rhodes piano. That is, it sounds like, but is not the same as playing a Fender Rhodes. So it’s a bit like that with photography. There are all kinds of filters that make a “look,” but the experience of waiting or delaying the gratification of something that will or won’t come out changes the way you behave with the camera. Making a book feels like making an album. It’s something complete.

Which book should we add next to our library?

All of Hagar Ziegler’s books.

Where can we get the book?

On my Instagram, Magasin III Jaffa Books.

Youval Hai, born in Yafo in 1977, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. He received a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design’s Department of Photography and Computerized Imaging, as well as an MFA from Bezalel. Hai is a member of Indie Photography Group Gallery, a cooperative photography gallery in Tel Aviv. He has staged several solo exhibitions at Indie Gallery and other spaces.

"The idea is that when there is no mirror there is less noise, and the camera is less intimidating. For me, shooting with a rangefinder is an attempt to produce an intimate photograph in an urban space. Here too I feel that I fit into a long tradition of street photography starting with Henri Cartier Bresson, through Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Bruce Gilden."

"The “patch” is interesting in the sense of a botched attempt to fix something. It’s funny that it’s also the name of a tool in Photoshop for correcting areas in an image, a tool that allows you to sample a certain area from another area. That’s a bit of what my eye looks for in photography."