How does a book come into the world?

This book is like a short sentence from a project that I have been working on for the past seven years. It doesn’t summarize a process but rather is a sweet experiment that succeeded. Over the past seven years, I have been traveling the world and become a nomad of sorts. Every two hours I post a photograph on Instagram, and my social media accounts have become my personal gallery. Since I carry everything I own on my back, I try not to have too many physical objects. This book, in its independent and reduced form, has enabled me to produce a physical object in a modest way. It’s very exciting to change your method of work from time to time, to think about photographs and see them in a different way.

The title of a book is like an intimate secret shared by a few. Will you let us in on it?

Tara Nomada—Latin for “The land of nomads”—is an expression that aptly describes my lifestyle, and it’s also the name of one of the hostels I stayed in while taking the photographs that are featured in the book. The photographs were taken over a two-week period in the summer of 2019, while I was traveling in Maramureș County (a region in northwest Romania), one of my favorite areas in the whole world.

Who did you collaborate with on the book?

I worked on the book with Nana Ariel and Uri Yoeli from Home Press in Tel Aviv. It’s a private, underground, and subversive publishing house that operates from the couple's home in the southern neighborhood of Florentin. Everything is handmade; we did page layouts and hand-wrote the texts. We printed the book with a home printer using paper we bought at a local art store. We cut out the pages, sewed, stitched, and numbered them ourselves. Then we approached independent bookstores (Hamigdalor, Sipur Pashut, and Tolaat Sfarim) and hand-delivered the copies. We didn’t make any proceeds from this book but we also didn’t lose money. I deeply believe in this path.

How long did it take to make?

If I calculate it from the very first moment that we started discussing the idea to the moment the first copy arrived at the Sipur Pashut bookstore, in total it was six months. But in terms of actual work on the book itself, it took us about a month. I'm a firm believer in only doing things I enjoy and love. It’s a very privileged kind of thought, but I see it as a way of life. That’s why the simplicity of the process was important to me; had the process been difficult, this book would not have seen the light of day.

How did you decide on the size of the book?

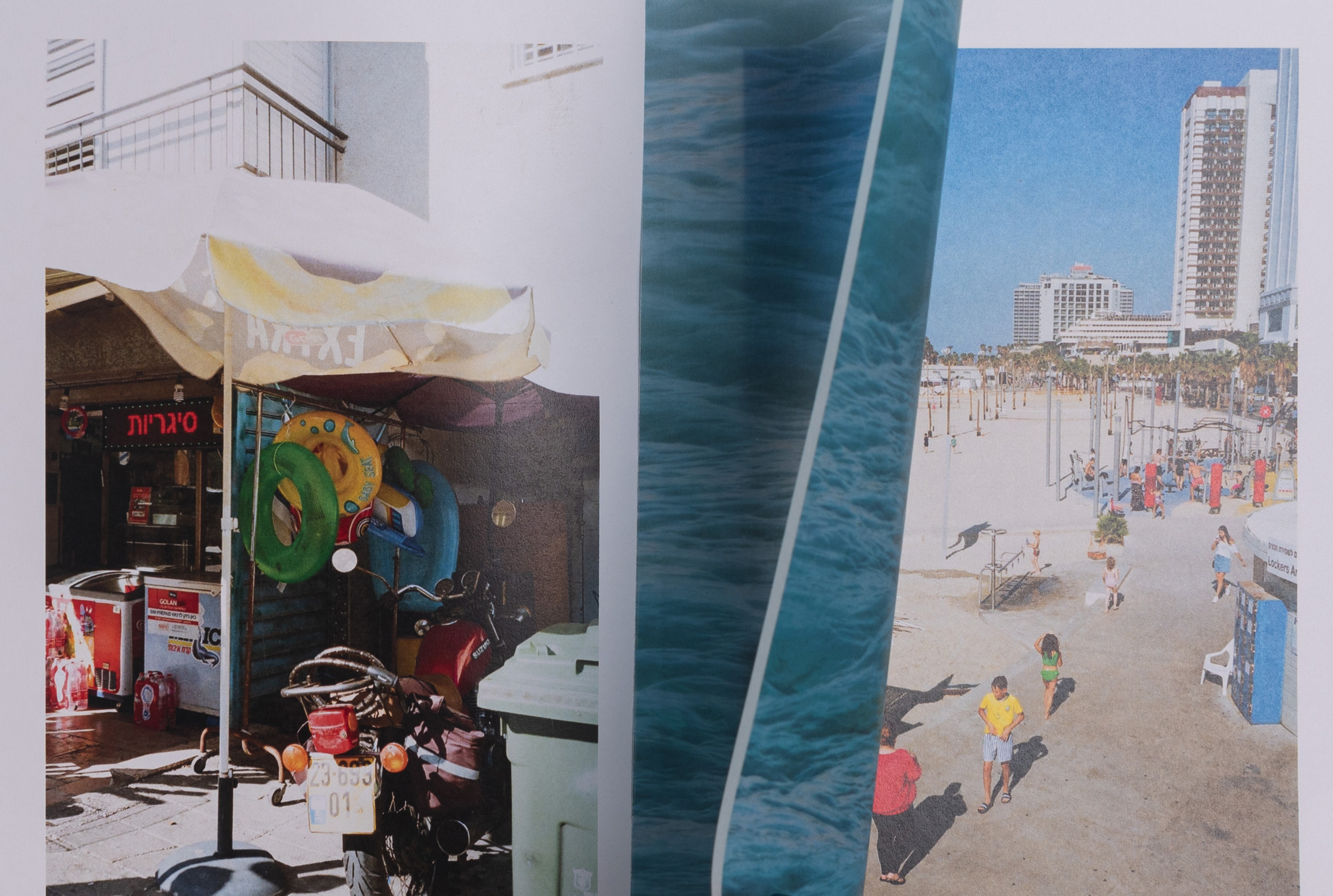

Everything was homemade, so it was clear from the very start that the pages had to be A4-sized at most, which gave us a lot of options. At first, we thought the book would be the size of a postcard—it seemed to fit so naturally with the story of my journey that this book conveys, and I also wanted the photographs to be large enough to give them the space they deserved. Unlike me, Uri is a pro at binding books and he suggested several options. Sewing the pages together was one of them, and this option allowed each photograph to have its own page. In order not to take unnecessary risks, we decided that each page of the book would feature a single photograph on one side, so that the paper wouldn’t absorb too much ink and rip.

I wanted to leave a classic, white passe-partout frame around the photos. In addition, we had to leave a clear area on the margins so we could sew the pages together. I guess I could say that reality dictated the size for us, but it’s also the size I’m used to working with because when I edit my photographs I do it with a home printer, I don’t really work with designers and I have no clue when it comes to design software. So I fold A4 papers, and sometimes I paste the images on the paper itself; it’s a very immediate kind of process.

How does this process correspond with your work in the virtual spaces online?

It’s a bit like posting a photo on Instagram and moving on with your life, in the sense that the book has already been made and now it’s in the past. Since then I have done two more books, both of which exist in single-copy editions. I really love to make books. Even when I work on my photographs for exhibitions, I edit them in pairs as I would for a book, and often I bind them together. It’s a good and convenient way to see if images work together in a specific space or on a wall.

It’s rare to come across a photography book that doesn’t feature a photograph on its cover.

I didn’t want to have an image on the cover, I wanted to have a clean slate. Tabula rasa. Maramureș is a hidden area, and I wanted the book to be a little bit like that. You have to be brave or curious to open a book without knowing anything about it.

The following is a question I have been meaning to ask you for years: Is the title of the project, Permanent Vacation, a nod to the Jim Jarmusch film of the same name?

Ha ha, no, not at all. I used to make lots of collages in the past, and in order to create them I would buy stacks of magazines at the Dizengoff Center shopping mall in Tel Aviv. One of my favorite magazines had published an issue that was titled “Permanent Vacation,” and the name was designed in a way so that the letters stood out from the page. This later inspired me to create a drawing with an engraving pencil. I have to say that I love everything related to this name. I love the Jarmusch film, and the rock band Aerosmith has an album called Permanent Vacation, and there’s also a great clothing brand for surfers in Australia that has the same name.

When was the dolphin image added to the logo of your project?

I created the logo in collaboration with the tattoo artist Glitter Not Tears; it was kind of a coincidence. I went to her to get a tattoo after four years of traveling. I had gone through an operation, and I knew then that I would have to undergo chemotherapy. I wanted a tattoo on the hand that was going to be injected during the chemotherapy. I wanted to have something that would break the ice when I got the treatments, something to talk about; something that would give me hope. I asked the artist to make me a tattoo that would include the words “Permanent Vacation,” and when she showed me the design, it felt like something was missing.

So we played around with it until we decided on the dolphin—which was mostly inspired by the cover of the album You Can’t Hide Your Love Forever by the British post-punk band Orange Juice, which I love. It also relates to my love for the sea. It turned out amazing so I decided to make it my logo, and I also created t-shirts with this logo.

Do you use this logo to sign your work?

I don’t sign anything, ever. I really try not to sign anything, unless I absolutely have to. It really stresses me out. When we finished working on the book, Uri and Nana asked me to number the copies and sign them. I had no clue how to go about it. It seems like such a permanent act. But it did make sense to put the logo on the cover of the book. I adore it.

Who would you dedicate this book to?

I would be glad if the people I met and photographed on my journey would get a copy of the book. These are very simple and generous people who opened up their homes and their lives to me.

What is it like after a book comes out?

It was truly fun to create this book and to see these photographs presented in another medium. The fact that it sold out within two or three weeks was incredible, unexpected, and deeply moving. It made me want to make more copies because suddenly it seemed that more people wanted it. I don’t even have my own copy. The copy that you borrowed from Uri and Nana is actually my copy, but I don’t really have anywhere to put it, there’s nothing I can do with it. I actually haven’t seen the book since the last time I went to the bookstores to deliver the copies.

Is there anything important you discovered about the process of book-making that you think everyone who wants to attempt it should know?

All you need is a printer, a pair of scissors, and some masking tape. Beyond that, I don’t really know. It can also serve as an amazing portfolio. It could be much nicer to hand in a portfolio that looks like that.

Do you already have any ideas in mind for your next book?

I have wanted for a while now to create an encyclopedia of the Permanent Vacation project, but for that you need a big budget. I have the perfect idea and concept, and it would be a lot of work, mostly dedicated to many hours of editing and sifting through my archive. Tara Nomada is an example of one volume or part of the volume dedicated to the subject of Maramureș, or craft; or maybe heaven. One day I’ll do it.

What was the first artist book you ever purchased?

After my military service, I traveled abroad with a friend. He already knew he wanted to study art at Bezalel, while I still didn’t know what I wanted to do next. In Paris, we hung out in various bookstores, where I first encountered Juergen Teller’s book. I knew his work through all kinds of magazines I loved in my teens. This book, the way it was edited, and the perspective it offered completely blew me away. Of course, I bought the book, and it remains my favorite book to this day.

What book should we add next to our library?

Wow, there are so many I would recommend. Hana by Hagar Cygler is stunningly beautiful and is a must-have in every household. Anna Yam’s new book, OLYMPUS, which binds together the works from her exhibition at the Ashdod Museum of Art, is wonderful. I would also recommend the book of Yuval Hai, who is my favorite photographer.

Where can readers get a copy of your book?

It’s sold out.

Dana Lev Levnat was born in Haifa, Israel in 1978. She obtained her MFA in Photography at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. In 2013, Lev Levnat left Israel and embarked on a global journey, during which she began her ongoing photographic project Permanent Vacation. This project was based on a single rule the artist determined for herself: every couple of hours she had to post an image to her social media networks; the published photographs had to be documentation dating back to the past 24 hours. Lev Levnat’s photographs document the places and the people she meets as she wanders through the world.