How did your book come into the world?

I’ve been photographing for many years, 16 or 17 years during which time I collected an infinite amount of materials without a specific purpose in mind. The act of sifting, the transformation into a story, and the organization around a theme were hard for me. I flew to the United States with my wife and children, and the trip gave me a framework from which the book emerged.

At the same time, I was attending a workshop with Sarah Filaire, which is something like a support group for working artists. Once every two weeks we’d sit together and go through our materials. It really motivated me during the process—to see that the materials are worthy of a book, which is something that isn’t easy to say about oneself. After the course, I continued with Noa Ben-Nun Melamed, and she really resolved big decisions with a simple yes or no. I photographed like crazy there. I could have made three books from the amount of material.

What’s it like to work with an editor?

Noa edited the content and the designer Ran Ben Ezra helped us with placement and flow. Noa is familiar with my work, and it was a very organic process. It was clear to me what her taste was, and we agreed on things very quickly. Sometimes it’s hard to let go of one image or another, but I could see why some photographs were more suitable for the book and why others needed to go. It was great for me to work with another pair of eyes, and we had the book ready in two months.

What process does the book embody for you?

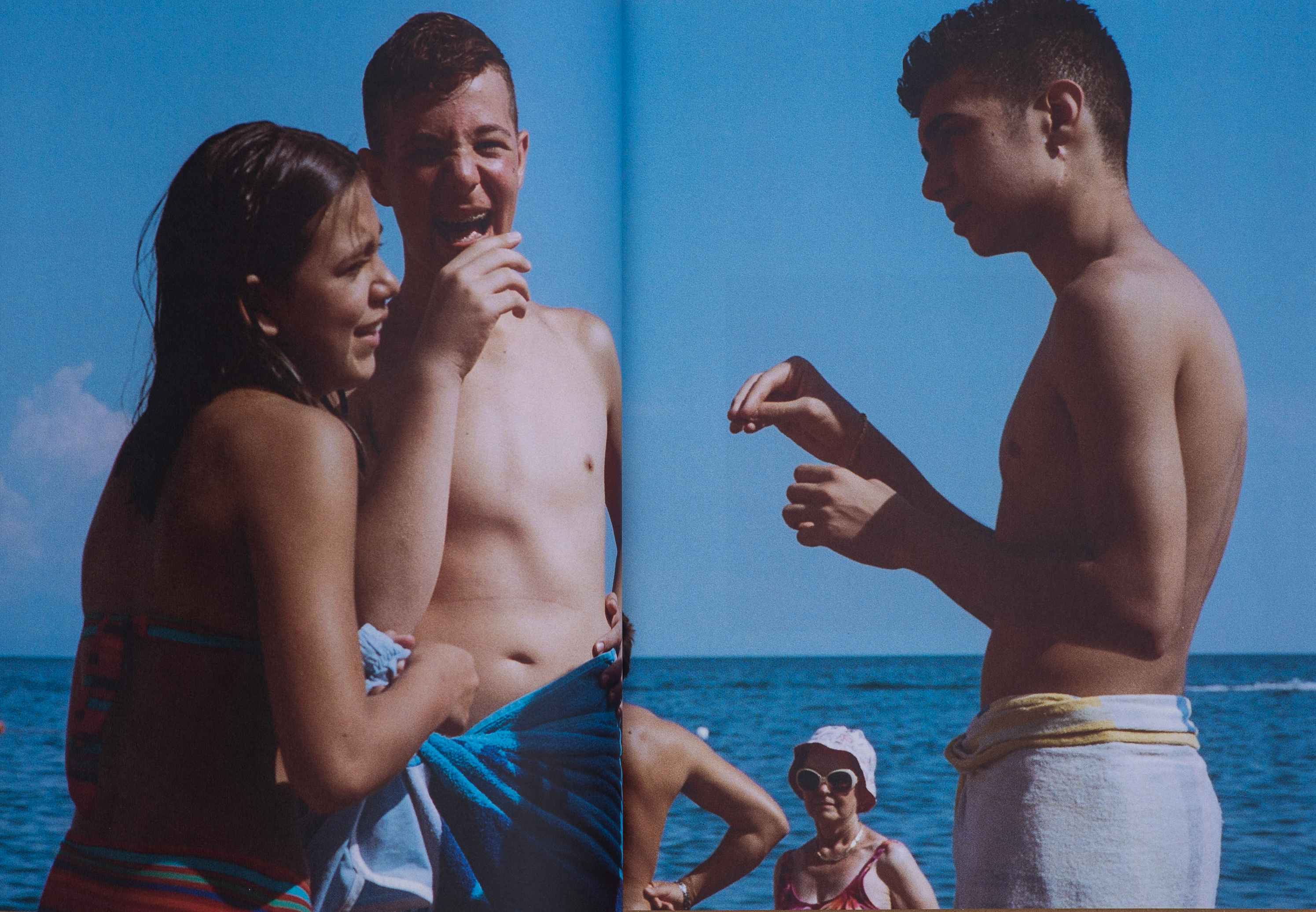

In a kind of self-declaration, I embarked on this journey in the tradition of American documentary photography, from Robert Frank through more contemporary photographers such as Alec Soth, and Joel Sternfall, who had the most direct influence on me. The central theme is the journey, but it wound up being photographs of people and less of places. What guides me in terms of photography has to do with William Eggleston’s idea of “democratic photography.” I want to photograph people in the same centered, direct, repetitive composition. It’s a measure of equality for me. The subject’s background and socio-economic status don’t matter. Everyone is positioned similarly, this is my guide.

And how does this relate to fashion?

I photograph fashion for a living, so my eye scans a person from head to toe. I think I choose pretty fashionable characters, in terms of their attire and attitude. My documentary photography is not fashion photography, but its degree of informativeness is catalog-like. It occurs to me naturally. People don’t usually know how to be photographed, so I direct them a little, where the light is. Minimal direction.

The title of a book is like a secret, will you let us in on it?

I called the book First Impressions, even though Noa strongly objected. She claimed that it was an apologetic name as if it were my first time photographing. I chose it because it’s really my first trip to the United States as a photographer who is expressing himself, a working photographer. These are first encounters for everyone, their first impressions of me, and vice versa. They have to decide in a second whether they trust me or not. Afterward, anyone who had asked for their picture and gave me their email was sent a photo, and there were quite a few who did that.

What would you like for the book to do out in the world?

First of all, I want to be a part of the tradition. I don’t know if I’m doing anything new, I’m exploring this tradition for myself. I want to convey goodness and understanding, something that connects people. The connection between the subject and me, that’s what I’d like people to feel.

What’s the connection between text and image in the book?

Everything moved quickly so we settled for minimal text. Photography is an exploitative field and I feel as though I managed not to exploit my subjects, the people I photographed. I’m not a photographer who asks for the names of people being photographed; even though I have a notebook I don’t open it, so I was left with the names of the places, and in hindsight, I think it reflects the connection of the people to where they live, to the spot where I met them.

What disappointments or difficulties were there along the way?

I always feel like I can photograph better, I have a never-ending need to improve. I don’t look back at my photos longingly; straightaway I want the next frame. I think it’s a photographer’s “thing.”

Is there anything important you discovered about bookmaking that everyone should know?

It was a lot less complex than I thought and that’s heartening. It took a week to do all the tests before printing. So it’s possible to make a book quickly and also be satisfied. And most importantly, you should feel like the people working with you understand you as a photographer and as an artist.

Who would you want to leaf through the book?

All the photographers I mentioned, although unfortunately, Frank is no longer with us. I’d be happy if photography teachers in Israel would show it to their students. When colleagues show your work, it’s extremely gratifying.

To whom would or did you dedicate the book?

I didn’t dedicate it to anyone, but a special thank you goes to my two uncles in the United States who helped me make the trip. One of them is also the uncle who gave me my first camera and hosted us there. I can say that it’s essentially dedicated to him.

What were the inspirations for the book?

Before I went on the trip I of course looked at The Americans. Many people mention August Sander in connection to the book, which is interesting because I didn’t do a “scientific” social mapping, but its visuals, and the directness of the compositions, were certainly on my mind.

Making a book is like...

Turning a new page.

What book should we add next to our library?

Sarah Filaire. She’s a legendary teacher at Hadassah Academic College, in Jerusalem and a walking encyclopedia of photography. She’s also a photographer of course, and I'm sure she has an amazing library.

Where can readers buy your book?

At HaMigdalor bookstore or via direct message on Instagram @Gilad Bar-Shalev.

Gilad Bar-Shalev was born in Jerusalem in 1981. He works in Tel Aviv-Yafo and the vicinity. He studied photography at the Hadassah Academic College in Jerusalem. Bar-Shalev is a member of the Indie Photography Group Gallery. His photographs, which draw from the tradition of 20th-century photography, strive to depict people in their natural environment and to maintain a balance between revealing them and preserving their inner world. In 2020 he presented a solo exhibition at the Indie Gallery, and participated in a number of group exhibitions including Local Testimony and the Photo IS:RAEL photography festival.