The book Maya and Me was published at the same time as your solo exhibition at the Petach Tikva Museum of Art. It all started with you uploading drawings from the last two years to Facebook, which gradually became an ongoing diary. I assume that the other things happened at the same time, but what came first – the chicken or the egg? The book or the exhibition? Or as we like to ask at Leafing: How does a book come into the world?

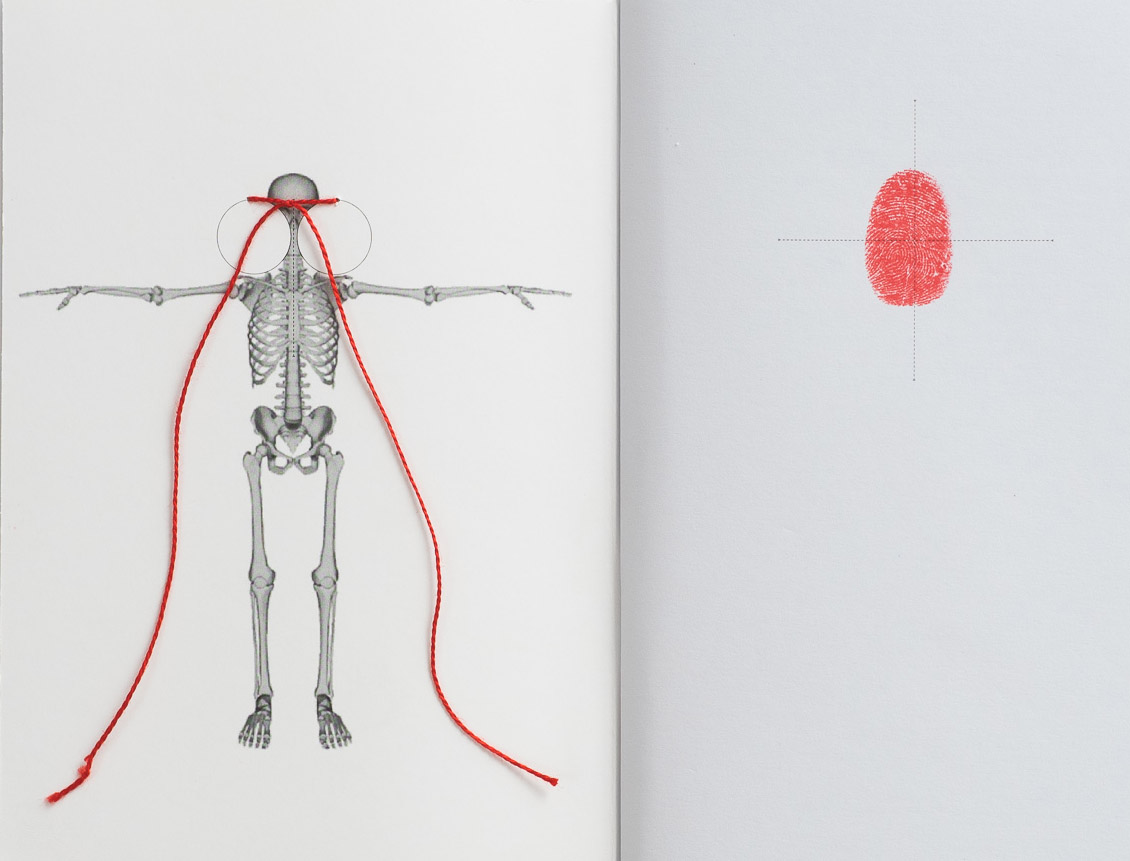

When the Coronavirus broke out in Israel in March 2020, it was two weeks after the close of my solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Artists’ House. I was still processing it all when the first lockdown happened. My daughter Maya and I hunkered down at home, while all around us was madness and uncertainty about where the world was heading. A sense of dread hung in the air. I made the first drawing in response to all that, not with Maya but by myself. I drew a human figure, and I also drew a pistol where her throat was.

Curator: Irena Gordon, installation photo: Tal Nissim.

Maya was a year and a half old then, and she drew a lot. I didn’t have a studio, but the need to draw was there, and it saved me. Every evening, after Maya went to sleep and I finished cleaning up the house, I had a pile of her drawings waiting for me. I was still new to parenting, and I was trying to figure out how to communicate with a little girl who was just forming her first syllables. At the same time, I had to try and hide from her the reasons why she couldn’t go outside or to her playgroup. I looked at the lines she drew and saw them as the most magical and purest moment of writing possible, free of all artistic criticism. It was a bit like looking at a plant that you know will bloom and watching it emerge.

But in practical terms, we were starting to run out of paper at home. I noticed that Maya didn’t use the whole page to draw on, so I had room for my own drawings, and that’s how the process began. The first drawing I did with her was of a gymnast. It stemmed from an attempt to animate the line she had drawn. At that time I felt isolated, I couldn’t go to work or out to see friends. I started posting our shared drawings on Facebook almost every day, and people started responding. And so, a dialogue was created with her and also with those who experienced the drawings online. It kept me sane. As time passed and the closures became more difficult, the drawings became more biographical, revealing what I had been trying to keep hidden.

How did the transition from such an intimate process to an exhibition and an artist’s book happen?

It wasn’t planned. I was at home drawing on an ever-dwindling supply of pages. I never imagined it would end up as an exhibition or a book. After a year, I realized that I had accumulated a lot of records and that they communicate with the world. People in Israel and overseas responded to the drawings, the New York Times wrote about the project, it had a resonance. I began to see a clear sequence and narrative; I understood that it was a diary on pages of paper that told a story, and from there creating the book was the next natural step. I wanted to create something that in its nature was somewhat timeless. Books can be timeless, like children’s books that accompany us from childhood to adulthood. In my experience, works of art have a life of their own and exist in a separate world from the world of books.

The longing to create something eternal is also reflected in the decisions you made regarding the book’s external appearance. It looks like a time capsule that records an elusive and fleeting moment in the lives of a mother and daughter. It comes across in things such as the pages of the book, which are not ordered numerically but instead give the ages you both were when you did each of the drawings. The pages of the book preserve the tactility of the plain paper. Tell me a little about the thought that went into these decisions, and about the experience of working with Avigail Reiner, the book’s designer. The drawings went through a process of double translation didn’t they, conversion into an exhibition and transformation into a book.

Yes, these are two different processes. The book came before the exhibition, and they developed separately. I tried to understand how I can translate the experience I had into a book. The first decision was that the book would only include Maya’s and my drawings, as opposed to the exhibition, which also contains drawings that I did on my own. In addition, I chose not to include all the drawings I did with Maya in the book, but to limit them and show only a part. When I got to the design stage and met Avigail, I already had a lot of accompanying texts. I decided to remove the dates that were on the drawings, to separate them from their proximity to the Corona period.

Working with Avigail, we thought of the book as a kind of hybrid between an artist’s book and a children’s book, a book that speaks in several languages and nods at several worlds. You are right that the materiality of the page was very important to me; I remember that at some point I came to her with an old copy I had of the book The Little Prince, and I said to her: “Look, I want that kind of page.” I wanted readers to feel the pencil on the paper. Throughout the process there was a lot of thinking about the material aspects. That’s why I didn’t look for a publisher, I wanted to have a say on everything.

And what about the cover? What’s the meaning of the drawing of the closed eyes on the cover? Are they the eyes of Maya asleep? Are they your eyes?

It’s interesting that you refer to sleep because the whole series of drawings referred many times to the experience of sleep and what happens at night. I wanted an image that could contain all of it, but not one that was already in the book. Toward the end of the process, Maya drew a lot of lines. It was a period when she didn’t sleep much, and as a result, I couldn’t sleep either. However, eyes are a recurring motif in my works. I deal a lot with eyes and crying. For example, for my master’s thesis at Hunter College in New York, I created a video installation in which you see a woman (my sister) with chains coming out of her eyes like tears.

The last double spread in the book is particularly interesting, because it’s clear that you made a number of bold decisions there. It’s different from the other double spreads, which consist of reproductions of your drawings. This double spread features a photograph of toddler Maya holding her drawing. You don't see Maya’s face, but clearly it’s her. This is a daring emotional and aesthetic choice, to expose your daughter to the eyes of readers.

Also your choice of text is raw and gut-wrenching. On the back of the photograph you printed the text: “You showed me the picture proudly and said: “'Mommy, wook, a smiwe,” and I understood that it was over.” I assumed this sober “over” refers to a number of things. It may symbolize the end of the joint creative process, the moment when you feel you can no longer correspond with Maya because she is starting to take autonomous ownership of her drawing. It is also possible that “it was over” alludes to the end of the period of childlike innocence that characterized the first two years of her childhood, before she realized that the world was asking her to record mimetic images, which imitate reality or communicate with it directly.

Yes, that’s what happened. One day Maya came back from nursery school and showed me a drawing she did, and presented it to me as a drawing of a smile. Even before it happened I knew the moent would come, because nursery school teachers have a tendency to teach children to draw the mimetic world, show them how to make images like a heart or flowers. I realized that the period in which I was her mediator of reality was over, that she already perceives things on her own. I also realized that the book is over.

The heartbreak was real. Regarding exposing her, I can say that before making the book I was (and still am) one of those parents who does not expose their children. For example, I don’t post photos of her on social media. But I made this decision because I thought about Maya who would one day read the book and look at her own hands, those little hands holding the page. It’s a kind of echo of the little girl she is now and a way to preserve her forever. A photograph is a moment frozen in time, and so is the book. There is something in the experience of parenthood that seeks to freeze moments, and this was a moment that I wanted to remain frozen and unprocessed.

If we are talking about exposure, I would like us to reflect on the moral issue that arises from your decisions. As artists, it is only natural that our biography will be a central building block in our work. And on the other hand, there is an instinct to protect memories and personal experiences and not turn them into an artistic product for all to see.

There was a moment, early in my life, when I realized that art is an indelible part of me. The ideas always came from life, it wasn’t a matter of choice. The first image I can remember as a child is of a watermelon in the bathtub at our house. We didn’t have room in the refrigerator at home, so my parents put the watermelon they had bought in the bathtub. I remember myself looking at the watermelon and thinking: “What a beautiful and strange image.” So I went and drew it. I had a lecturer at Hunter College who did abstract paintings. She once told me: “’I’m not like you. As soon as I close the studio door, I symbolically close the door on life.” I wish I could do that, but I’m not like her. I am always waiting for life’s door to open.

It is interesting to read Maya and Me as another chapter in an artistic story you’re telling, through which you share your own experiences on subjects such as physicality, femininity and pregnancy. The current project was preceded by the performance The Last Performance of the Fax Machine from 2018, in which you compared the process of the obsolescence and irrelevance of the fax machine to the situation of a pregnant woman. In 2019, at the Manofim Festival, in the exhibition Nurse, Nurse, you presented the sculptural installation Shaddai, where you created sculptures of women covering themselves up while nursing. In the same year you also created Full Hands, a work in which you drew on your stomach and documented the last week of your pregnancy. To these you have now you have added the experience of parenting.

Many female artists deal with motherhood as a strong core of their work. It makes me happy that female artists are not afraid to say “I am also a mother” or “I am a mother.” The flowering of motherhood as a source of creativity is positive, but nevertheless, I don’t want this framework to define all of my work because it’s not its only essence. The word “chapter” is very important in this context. I once said in an artist talk that if all my works were placed side by side like frames from a movie, they would tell the story of my life. Just like I cannot predict the sequel of a movie, I don’t know what the next chapter will be. Not knowing is exciting.

I did two degrees in art, I am an active artist and a great consumer of art. As one might expect, I am constantly engaged in the intellectualization of art and fight it at the same time. I think the success of the current project lies in the fact that I wasn’t trying to make art, I was just drawing with my daughter. It was mainly a joyful process. If Corona had not happened, I probably would not have created this project, because I would have told myself that it was a banal or kitschy idea. There was something about Maya's line that was full of authenticity which I missed in the creative experience. Looking at her reminded me of my desire to draw that had waned over time, the amazing moment of the joy of discovery and originality in the act.

While I am not a mother yet, but sometimes hope to be, I am most certainly a daughter. In your book I recognized the symbiotic emotion of concern that permeates between parents and children. It resonates in drawings like the one where you turn Maya’s red scribble into a spirit you’re trying to ward off while she’s engrossed in play; or in the drawing where a series of black circles that Maya drew one on top of another turned into a stormy picture where you drew wolves lurking for prey.

After reading the book, the first text that came to my mind is Natan Alterman’s poem Shir Mishmar, which he wrote for his daughter Tirza Atar in 1965. Alterman, like you, enumerates the real and imagined dangers that his daughter must protect herself from: “Protect your soul, your strength protect/ Protect your soul./ Protect your life/ Your consciousness/Protect your life./ A crumbling wall, a roof on fire, a shadowed hole/ A stone is slung, a nail is sharpened, or a knife” [translation: Achinoam Nini]. Tirza responded to this warning in Shir Hanishmeret: “I am cautious of falling things. / Of fire, wind, songs. / All sorts of winds strike the shutters. /All sorts of birds do speak. / But I guard my soul from them / Nor do I cry. / I remember that you asked me to be blessed / I am blessed.” Is this book to some extent a “guardian song” from you to Maya? Or is the warning a reminder for yourself about the challenges inherent in the parenting experience?

When the book was published, someone asked me if it was suitable for a five-year-old. I answered that the book is suitable for children who do not yet know how to read , because as you say, it is a book that deals with my anxieties regarding both of our existences and wondering how well I succeed or fail in maintaining them. Throughout the joint creative process, I kept asking myself: is Maya drawing because she wants to draw or is she drawing because she wants me to keep responding and being with her? In the mother-daughter experience, this is an important question that is asked – are you here for me or am I actually here for you? The book begins with me observing Maya, and a reversal takes place during which Maya is the one observing me.

There is a reference in the book to a poetic moment when Maya got glasses. When it happened in real life, I decided that I would also wear glasses so that she would feel comfortable. For a whole month, I walked around with glasses without lenses. My sister laughed at me and said: “Reut, she has to deal with it. You can’t always mediate everything for her.” And I said to her: “I think I’m doing it for me.” I wanted to understand how she sees the world.

A significant part of the book’s charm stems from the originality of the practice you formulated. In the beautiful text by Maria H. Loh, she calls the genre you created “maternal surrealism.” Do you resonate with this idea?

This is a fruitful notion because it sharpens the differences and the motivations. From a practical point of view, the process of the Surrealists was continuous; And when I worked with Maya it was a fragmented experience. Yes, there were moments in the journey that turned into an almost material and artistic dialogue. For example, there is a drawing where I am seen lifting my shirt. It was created because I was waiting for the moment when Maya would draw lines that would look to me like a torso , and that I could base myself on.

I couldn’t tell her: “Maya, draw me something that looks like a torso.” I was just waiting for this moment to happen, and the anticipation was exciting in itself. Maria greatly influenced me and the way I look at and feel art. I met her during my graduate studies, and she brought a depth that I hadn’t met before in people who look at art. She recognized things I hadn’t even told her. It’s a great honor that she wrote the text for the book.

You called the book Maya and Me. Is this a gesture that emphasizes the fact that her drawings became a platform for you?

The inspiration for the title was John Lennon’s song, God. There is a line in the song where he sings: “I just believe in me / Yoko and me / And that’s reality.” There is something in the sentence that captivated me. I listened to Lennon a lot when Maya was born. John Lennon and Yoko Ono were a kind of single capsule against the whole world, and when I was with Maya at home during the Corona period it felt like that. Just me and her, a capsule against the whole world. Lennon sang “that's reality,” and that was my reality. The reality is of course broader; Maya has a father, my partner, and we also have a dog. We do not live alone. But there was the feeling that the world was closing in and we were only seeing each other.

Making a book is like…

It’s like the children's game where you place blocks on top of each other and hope they don’t fall. Then comes the moment when there is a tower, it stands and has a life of its own, and then you have to maintain the balance.

What book should we add next to our library?

Vered Aharonovich’s book. It’s a magical pop-up book that is a work of art in itself.

Where can readers get buy your book?

Maya

Reut Asimini, born in Tirat Hacarmel, 1983, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. She completed her BFA at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem and her MFA at Hunter College, New York. She is a graduate of the Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia, PA. She is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work includes drawing, murals, video installation, and sculpture. A central part of her work is the constant response to daily life events, with the works a continuation of something that life started. Her work has been shown in solo exhibitions in Hanina Gallery, Tel Aviv Artists’ House and the Petach Tivka Museum of Art.

"Maya was a year and a half old then, and she drew a lot. I didn’t have a studio, but the need to draw was there, and it saved me. Every evening, after Maya went to sleep and I finished tidying the house, I had a pile of her drawings waiting for me. I was still new at parenting."

"I kept asking myself: is Maya drawing because she wants to draw or is she drawing because she wants me to keep responding and being with her? In the mother-daughter experience, this is an important question that is asked – are you here for me or am I actually here for you?"