How does a book come into the world?

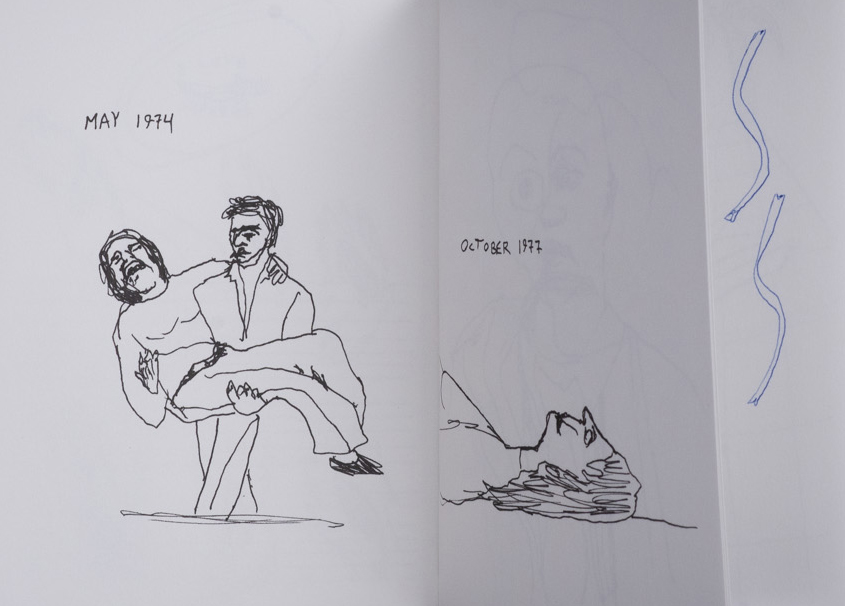

A thing is created from something. I started working on the project I called “Flora Palaestina” in 2003, while I was working on the “Aerial Photograph of Gaza” project, which I did after the death of my father, Yossi Karni. My father was stricken with Alzheimer’s at the age of 62. I drew him for about 14 years, until the day he died. He was an orchardist and entrepreneur, and while he was ill, they named the Karni crossing for him—the point where goods cross between Gaza and Israel (west of Kibbutz Nahal Oz).

I live near my childhood home, on the edge of orchards. I was physically close to the yard and my parents’ house. My father passed away in the summer, with a light blue pique blanket covering him. When he died, I said to myself, I’m taking this blanket and making a “blanket work” from it. I started drawing blue grids and inside I wrote sentences I had heard at the time on the news related to the Karni crossing: Karni crossing closed, opened, attack at Karni crossing. I was very preoccupied with this duality between the personal and the public. It was like taking a second look and seeing the same thing only differently; a mental space affected by my father’s illness and my mourning him.

A friend saw the drawings and said to me that they look like aerial photographs. I started searching for aerial photographs and found the office of Albatross, a private aerial photography company. Inside the Gaza folder was a fascinating slide that I couldn’t figure out what I was looking at. It had Xs and lines, and they explained to me that the big Xs are roads the army had cleared into the Jabalia refugee camp for control purposes; and the lines on the roofs are stones placed there so that the tin roofs don’t fly off in the wind. I walked out of there and said this was going to be an exhibition. All the large works in this series are based on an aerial photograph of Jabalia. I drew them during the second intifada. I said to myself, look at the photograph of the refugee camp, at the roofs and yards, and draw them. Don’t say: I didn’t see; instead, look at this scary, difficult, and dark thing. Like looking at my father during his ongoing illness.

It was a kind of journey of failure. All the experiments, the abstract, the concrete, in which I tried every possible material, on canvas, on tin, Plexiglas, and glass, became exhibitions. The first, at the Kibbutz Gallery Military Firing Area 2, curated by Tali Tamir in 2002 and the second, Aerial Photograph of Gaza, at the Ein Harod Museum, curated by Yaniv Shapira in 2005.

How does one go from drawing a refugee camp to drawing flowers?

During the process, Tamara Rickman, an artist I really like and respect, said to me, “I want you to draw me flowers.” I said, “Tamara, what’s going on?” And she replied, “In your bathroom, I saw a really beautiful watercolor of flowers. Draw flowers for the exhibition I’m going to curate, big, erotic flowers.” It was an exciting statement because Tamara saw something I hadn’t noticed. Maybe the passion in my flower drawings.

At that time, Tamara and I were reading Greek plays in a book club. I tried drawing flowers as she asked, and nothing worked. Then I came across a poster for Kew Gardens (the London botanical garden, one of the most famous in the world), and I understood that that was what I was going to do. Botany. Botanical drawing has its own rules: the image is in the center, with no background, and on the right are the details of where the flower was picked, the date, and its Latin name. I adopted the rules, but not really. I followed and went around them. Let’s say, I didn’t draw every single stamen.

The first thing you see on both sides of the book when you open it is the dedication to your mother. Would you say that Aerial Photograph of Gaza was a tribute to your father, and Flora Palaestina is a tribute to your mother?

Yes, but I only realized it in hindsight. My mother was born in Kfar Yehoshua, the daughter of pioneers who came with the Third Aliyah. She had a teacher who thought it was important to teach children about nature and culture, to connect them to the place, to raise “children of the land” as they called it then. He had taught them nature lovingly, and my mother developed a passion and deep love for wildflowers. It was pretty annoying for me as a kid. As children, we would joke that she was happier with the flowers than with us. When we would say something to her about it, she would say, “They don’t talk back.”

When I started painting wildflowers, it was from this almost childhood-like place. You hear the ancient voice, this love, and it annoys you, but it’s already absorbed in you. My “Eureka” moment was when I realized I was going to draw only flowers that I had a personal connection to, and I would bring them to the studio and draw from observation, not photographs, and write about them. These are diary works. I realized I would put the biography inside.

You’ve created a kind of flower “field guide” that’s a hybrid of the private and the public. When did you realize it was going to be a book?

I continued to draw flowers for a long time. I made engravings, plates, drawings, and paintings. In 2013, Arik Kilemnik, the director of the Jerusalem Print Workshop, suggested I do a series of engravings in the workshop, and I called the series “Flora Palaestina.” Every week, I drove to Jerusalem on Route 443, stopping on the way at places I had marked for myself, and picking wildflowers at the checkpoints. At the end of the process, I wanted to show them and turned to Ron Bartosh. He told me straight away this is the material for an artist’s book. He was the inventor. I don’t think I would have gone for it without him.

The book’s title is an enigma. Can you elaborate?

The name “Flora Palaestina” is the botanical term for the flora of the region (including the territory of Jordan). The interest in botany as a regional science began in the British Mandate period. In the 1960s, the Academy of Sciences published eight huge volumes called Flora Palaestina. They have amazing botanical paintings and texts about each weed. I bought them at a secondhand bookstore and they’re in my studio.

In 2013, in the midst of the project, there was an exhibition of botanical painters curated by Tali Tamir at Beit Uri and Rami Nehoshtan in Ashdot Yaakov. Among them, Bracha Avigad and Ruth Kopel. Kopel’s drawings were published in Flora Palaestina, but this was the first time I was seeing the originals. Their beauty astounded me. I wanted my book to be like a botanical book. Of course, the book’s title had a political charge that can’t be avoided, and that’s important to me.

It’s a complicated decision to call it that, and not, for example, Flora of the Land of Israel.

I touch delicately on the title of the book, and for me, it’s best to leave it that way. It’s a scientific term. Everyone can decide for themselves what it means to them. When Ron Bartosh presents the project, he presents it as completely political, but what matters to me is what Maya Bejarano writes in the poem at the beginning of the book, “First there was a wonder.”

What’s the origin of the poem?

In 2005, I showed two projects at the same time, Aerial Photograph of Gaza in a solo exhibition at the Mishkan Museum of Art in Ein Harod, and a series from Flora Palaestina, at the Bat Yam Museum in the exhibition The Flower in My Garden, Sayings in Flowers. I didn’t invite anyone to see the flowers because I thought people might not come to both of the exhibitions that were running at the same time. But I did ask Maya Bejarano to go and see it. Maya has a very deep ability for observation. After she saw it, she wrote the poem that’s at the beginning of the book, which captures in a deep way what I couldn’t even grasp then.

In the book, you work a lot with poetic texts. For example, with the calendars of Omanut La’am, the longstanding cultural enrichment program that brings art and culture to the periphery, and with other texts that you weave into “flower arrangements.” Can you give an example of the connections?

I really love poetry, and I loved the calendars with poems that Omanut La’am published. I would hang them on the wall in the kitchen next to the table so my kids would learn some poetry. At the time, it was also a daily planner for the house, and I would write on it stuff like “dentist,” “English class,” and “supermarket.” At some point, I decided to take the calendars that I had saved over the years and add a flower to each page and poet. I understood in hindsight that I had added another tier to the calendars: my family time and the flowers’ time, which also includes seasons, blossoming, and withering. And there are many other influences like the Greek plays I was reading with Tamara, which found their way in. For example, the words “Before the Odyssey” were included in a drawing of a poppy picked in a eucalyptus grove near a military camp on Tu B’shvat.

And there’s also Japanese influence, in the meter of the text, right?

Yes. I took classes with Prof. Yaakov Raz in the Department of East Asia Studies, in the 1990s, and you could say that there is some of my interpretation here in terms of Zen and Japanese aesthetics, as I understood them. Of presence, absence, emptiness, decay, and making room for old age, sickness, and flaws. In Japanese painting, the text appears on the side, like in a botanical drawing, and there’s a lot of importance to the blank, the white of the page. And also in the way the color is applied, these are applications of paint that emerge after long observation and searching for the precise color on the palette. Rawness and freshness, the way the paint is laid on the surface. Also, the encounter with Japanese poetry was influential.

So you “just” wandered around and picked flowers to study?

It was very important that I collect them myself. Look, when I started, these were just childhood flowers that I have a connection to. It was my vision of my mother’s generation, of “raising children connected to the place,” of the didactic games I grew up with—flower lotto, games for four players, “Who has a common poppy?” When my mother would go for a hike she always had a bucket and shovel in the car. She would dig up the flower she loved along with the soil and then re-plant them in our yard. Her connection to wildflowers was personal, passionate, and law-breaking. She’s over 95 years old, and in her garden, she has a tiny wild hyacinth given to her by Amnon Wentik in 1940. Every spring when the flower starts to bud, she tells the story about him and about how he died in the war in 1948. And suddenly, I find myself picking flowers. If any of the botanists I go on surveys with knew I did that, they would throw me over a cliff. But it’s important for me to capture that immediacy; you can’t get it from a photograph. There is a lot that is hidden in the book.

Such as?

I did the series of squills while drawing a project on Route 6. I enlarged an aerial photograph of the northern and southern parts of the road that were under construction. This was a map by landscape architect Dafna Greenstein, who shared her thoughts with me on how to preserve the wonderful landscape and flora of the Menashe hills and area as the road destroyed it. She said botanists were collecting seeds along the road, which will be replanted after the construction. I was moved and impressed by the thinking. The maps she gave me had a list of wildflowers that had been uprooted and were to be replanted. I was very excited by the list (p. 145), and made my own calligraphic interpretation of it for her. I called the work “Now These Are the Names.” This was during the Second Lebanon War, but I wasn’t fully aware of the connotations back then.

So, to draw on your last point, what about the politics of flower guides?

I’m not a fan of flower guides and I don’t have one at home. I play amateurishly with the names of the flowers in the book. For example, I call the entire group from page 60 gezer kipaḥ [Daucus carota subsp. Maximus], but they have other names, I don’t know which is which, gezer kipaḥ [daucus carota], nirit hakama [ridolfia segetum], amita kaitsit [ammi visnaga]. So, I scattered the names throughout the series, even if they aren’t the most accurate. Or, for example on page 64, amita kaitsit, it also says there “concrete barrier 443,” because it was growing alongside a concrete barricade that was blocking the access to Route 443. It was important to me to note the specific and harsh place where it was picked.

You created your own kind of hybrid for how to “define” a flower.

The names of the flowers are important to me. This is also my view of “Zionism,” to use that clichéd word. Finding names that would be “connected to the place” was a Zionist project par excellence. They went to intellectuals for names for flowers that will concretize Jewish history and the connections to the place. So I scattered names in a not-so-responsible way, but that’s right for me. And there are also mistakes. For example, Tali (the designer) gave a huge page to cyclamen that I forgot I had left in an acid bath. It was a plate that should have been thrown out, but she enlarged it. It has to do with the Japanese influence, to live with the mistakes and the erasures, to give space to the random within the meticulous book. Like walking down a path, and over here is a lizard passing by, and over there something that has fallen. Like walking down a road and seeing where it takes you.

In this context, something very interesting is happening in the connection between the index that appears in the book and the works. Going through the index one has to imagine the size of the works themselves in relation to the size of the flowers, compared to their size in the book. All these movements activate the imagination, a little like Alice in Wonderland.

That was the designer’s suggestion to give the whole index the same value, along with the Hebrew and Latin names of each flower, and basic details of the drawing. This is the opposite of the exhibition, and of course, nature.

And the yellow cover?

Telepathy! I wanted to tell you that the plan for the cover was a textbook. But then Larry Abramson’s book Botanica came out with a similar cover, and based on the same sources. I definitely wanted a canvas cover, like old science textbooks. When I saw the yellow color—that was it for me. There is something about it that is very non-didactic and eye-catching. I think the choice of cover is one of the book’s successes. Aya Maron, a curator in the Department of Israeli Art at the Israel Museum, wrote to me that it was “like receiving a bouquet of flowers and sunshine.” It was an emotional decision.

What’s the next book?

Now, I’m making a book that will be a sequel to this project, about inventories and scrolls. I’m going on botany tours that take me to places I would never have reached on my own. The large papers are inspired by a Dürer drawing I saw on Facebook. He scattered his botanical drawings over a wide piece of paper, and I said to myself so can I.

Is there something important you discovered about making books that everyone should know?

It’s jumping into a very deep ocean.

Who would you want to leaf through it?

I wasn’t sure who the recipient of the book or the flower paintings was. It was important for me to be precise, not to pay lip service. I was pretty panicked that I would get stuck with all the copies, but the first edition sold out completely. I was shocked that people were so excited. Someone wrote to me, “I’m bringing it as gift, instead of wine and flowers.” On the other hand, I brought some books to a botany group tour and it annoyed them that I’m not accurate. For me, the spirit of the flower is important, to give a reminder of it. Even wilted flowers, not just those at their peak. I’m glad people see the book as something more than “I like this, I don’t like that.”

What book should we add next to our library?

So many artists I really like have made wonderful books, it’s hard for me to choose; Frances Lebée, Nurit Yarden, Noa Ben-Nun, Ronit Shany, and Gary Goldstein, whom I met at meetings of Omanut La’am was my first encounter with artist books.

Where can readers buy a copy of your book?

On my website.