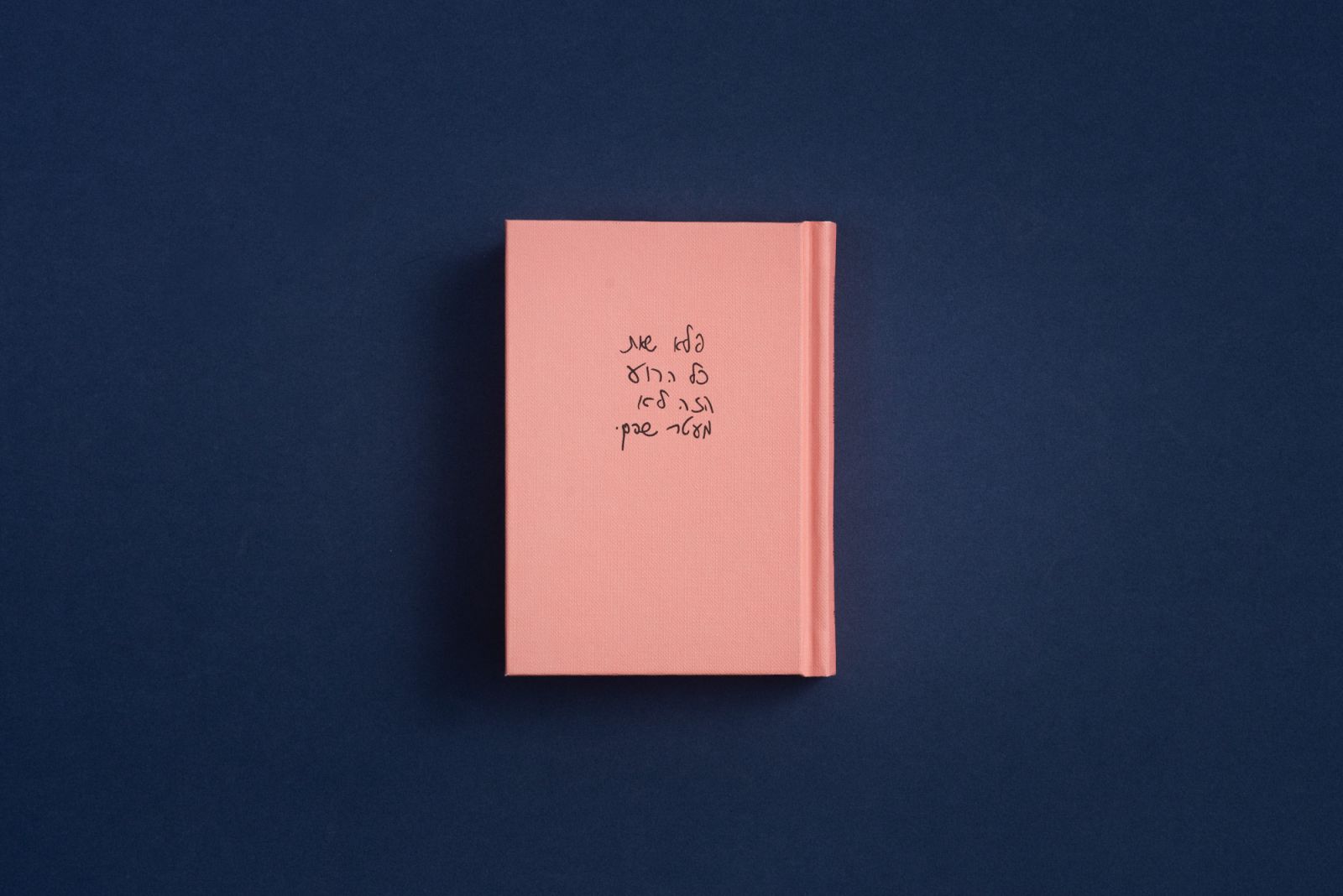

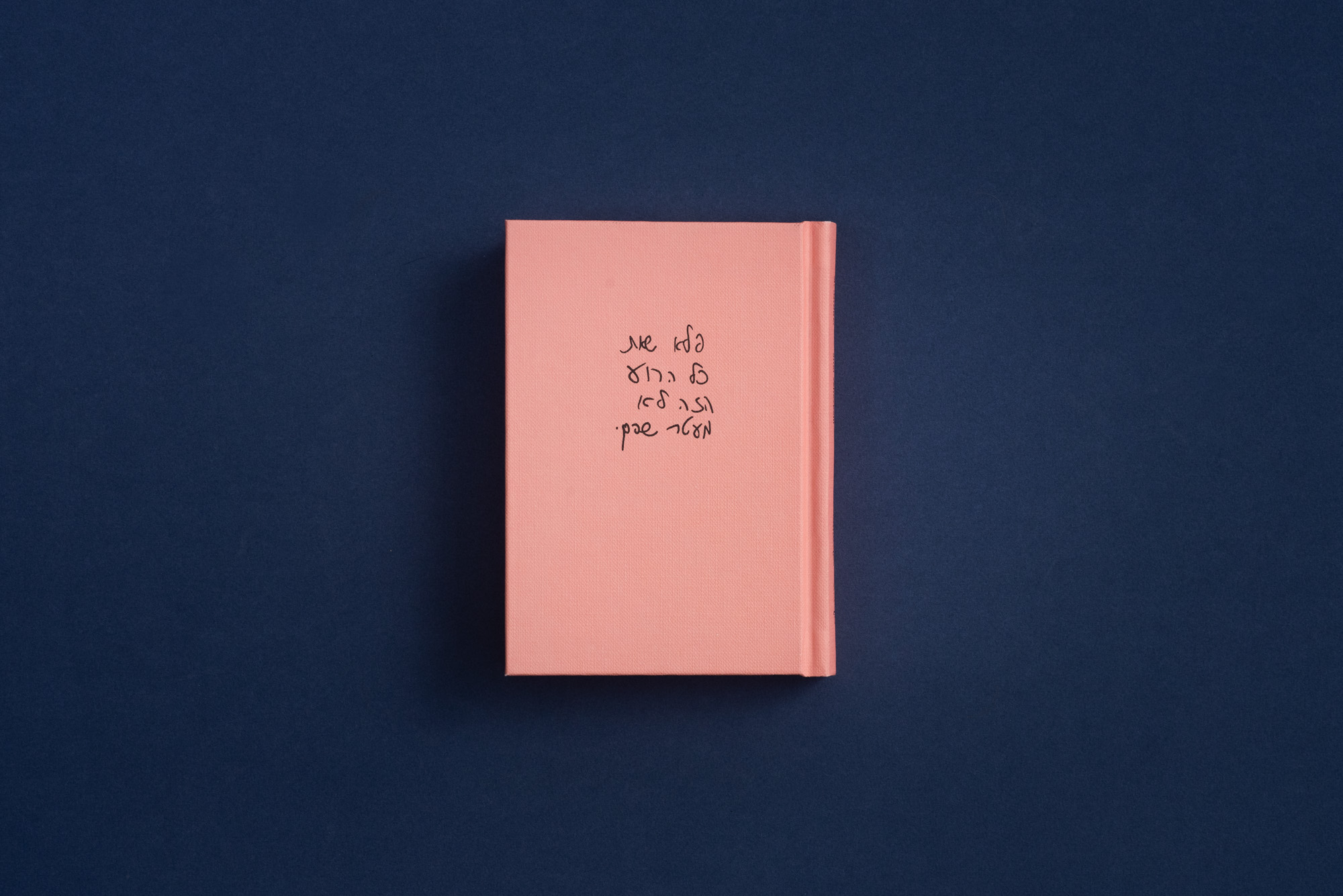

I thought we should probably begin our conversation with a discussion about the title of your book. The name of the book in Hebrew, which is not the same as in English, but more of that later, translates as follows: “It is a wonder that all this evil is not adorned with a mustache.”

In the wonderful text written by Doron Rabina, he makes a somewhat dramatic statement: “Evil, for that matter, will have a face, and it will wear a mustache ... It is an emblem of the unmatchable Hitlerian evil; the indescribable, immeasurable evil that has no proportion… Like a Hitler mustache on the face of evil, Yehezkelli’s drawings perform as an attempt to set a scale for reality; as a medium for begetting a self from the pathos (that went beyond measure) and for self-deprecating (that’s too small to measure).”

Do you find that Rabina’s observation correctly represents what you were seeking to express through the drawings that appear in your book?

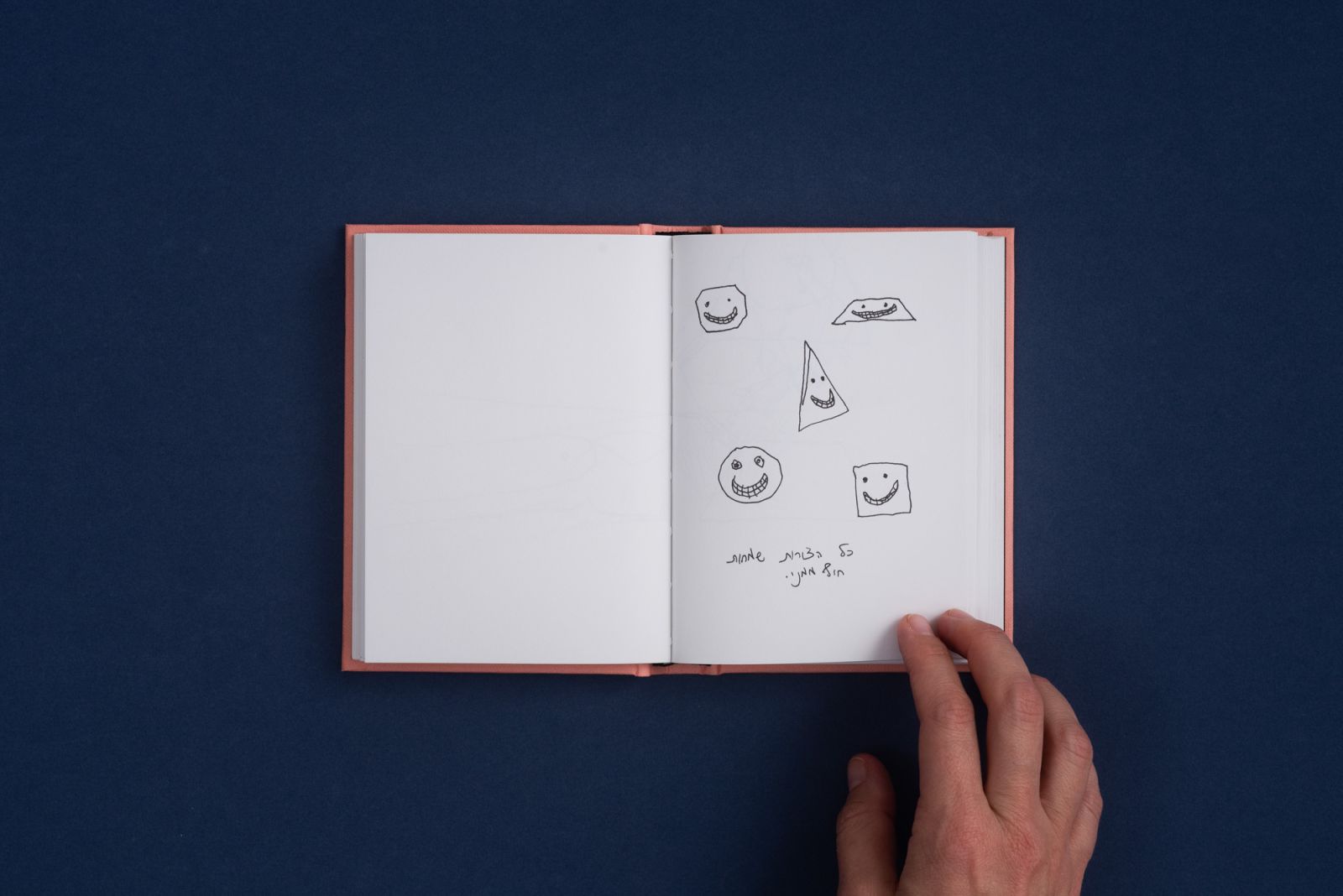

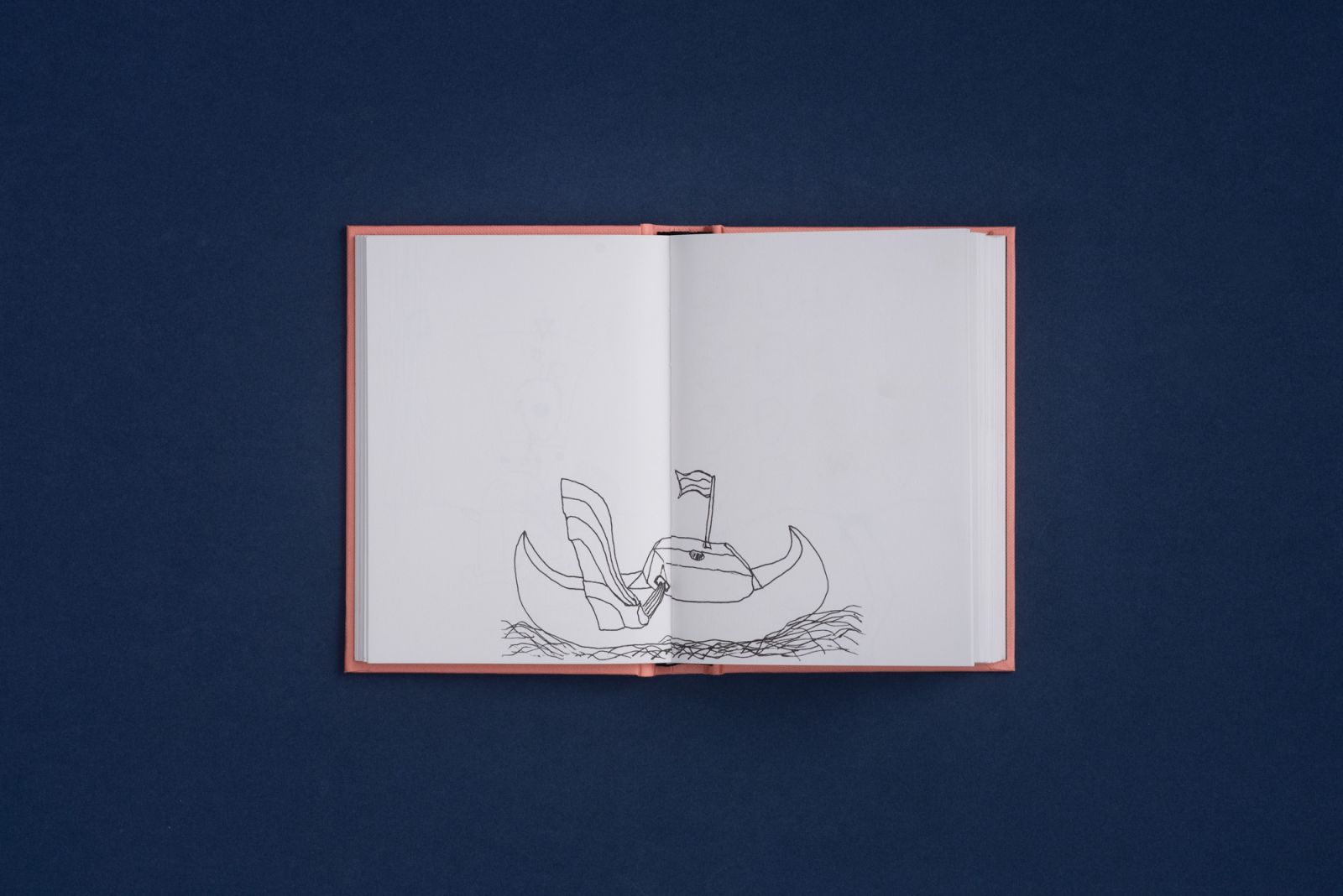

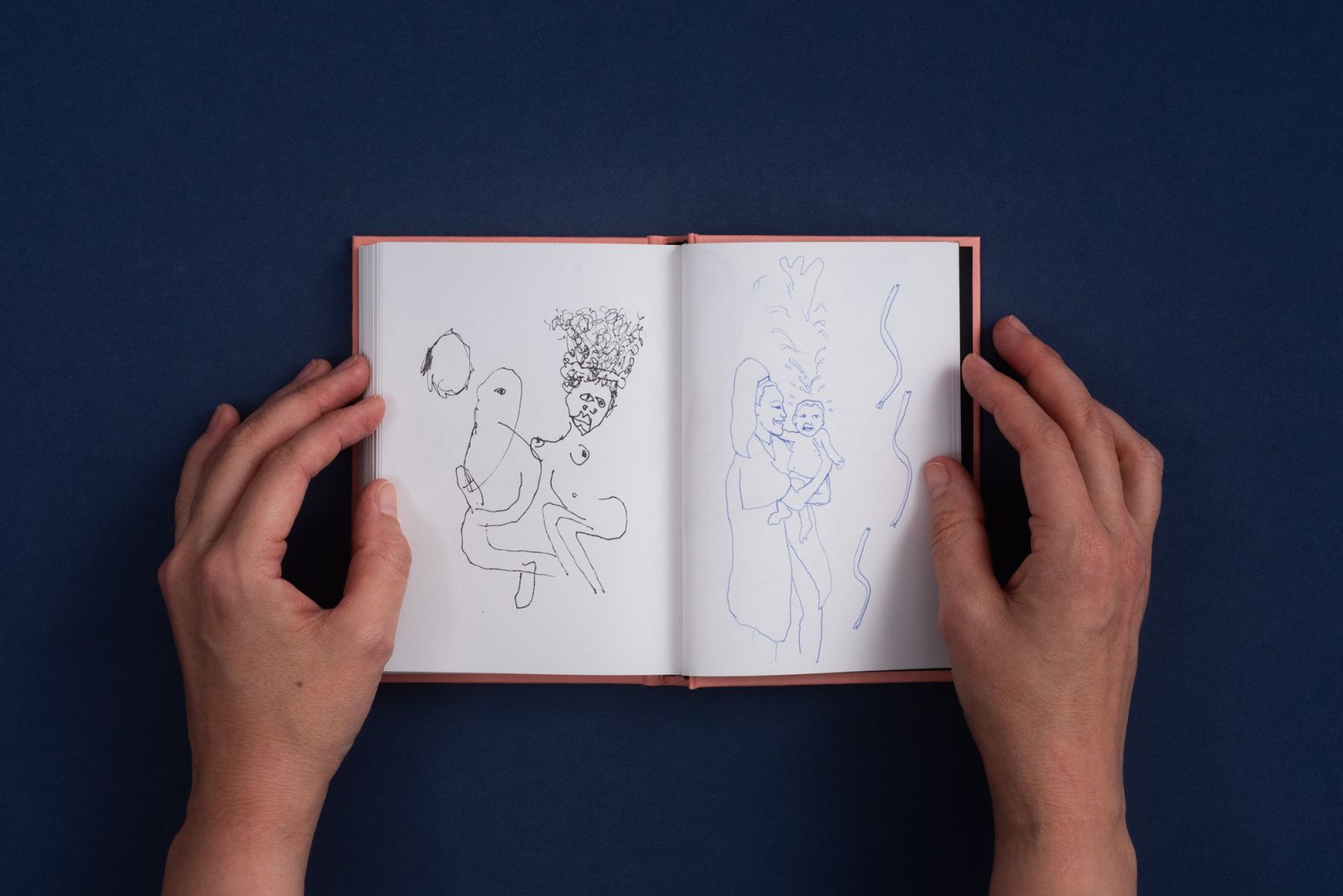

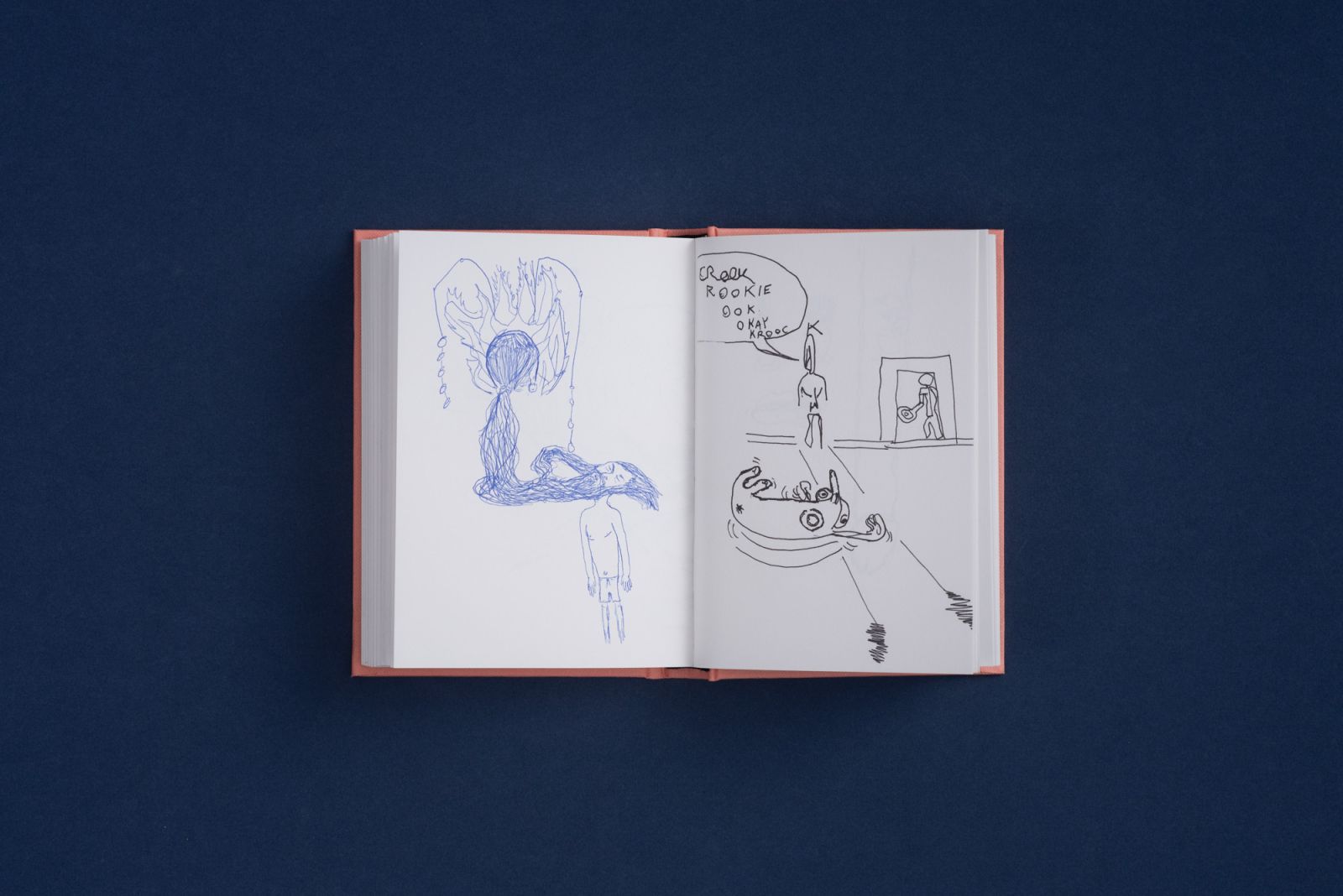

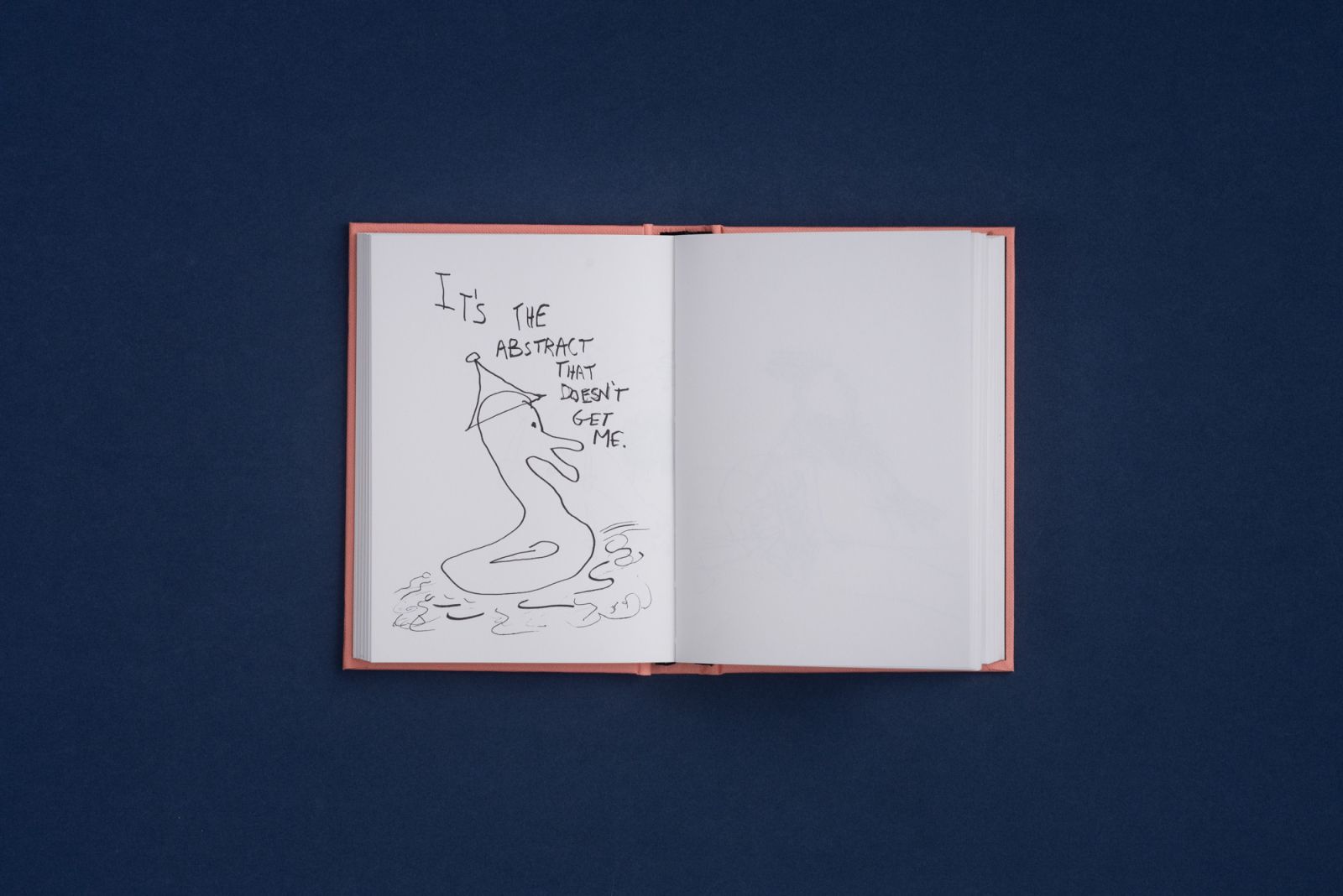

I’ll start by stating that Doron Rabina’s interpretation, which I really like, is a very subjective one. I think that he touched on many essential aspects of my book, which I couldn’t really see while I was creating the drawings. There is something quite prosaic about the book in terms of the everyday quality and the randomness of the themes and forms it presents; upon leafing through it, it might seem to the reader that the drawings were doodled almost as an afterthought. On the other hand, I wanted the overall contents of the book to create a stirring and explosive impression, or to offer a macro viewpoint of the world.

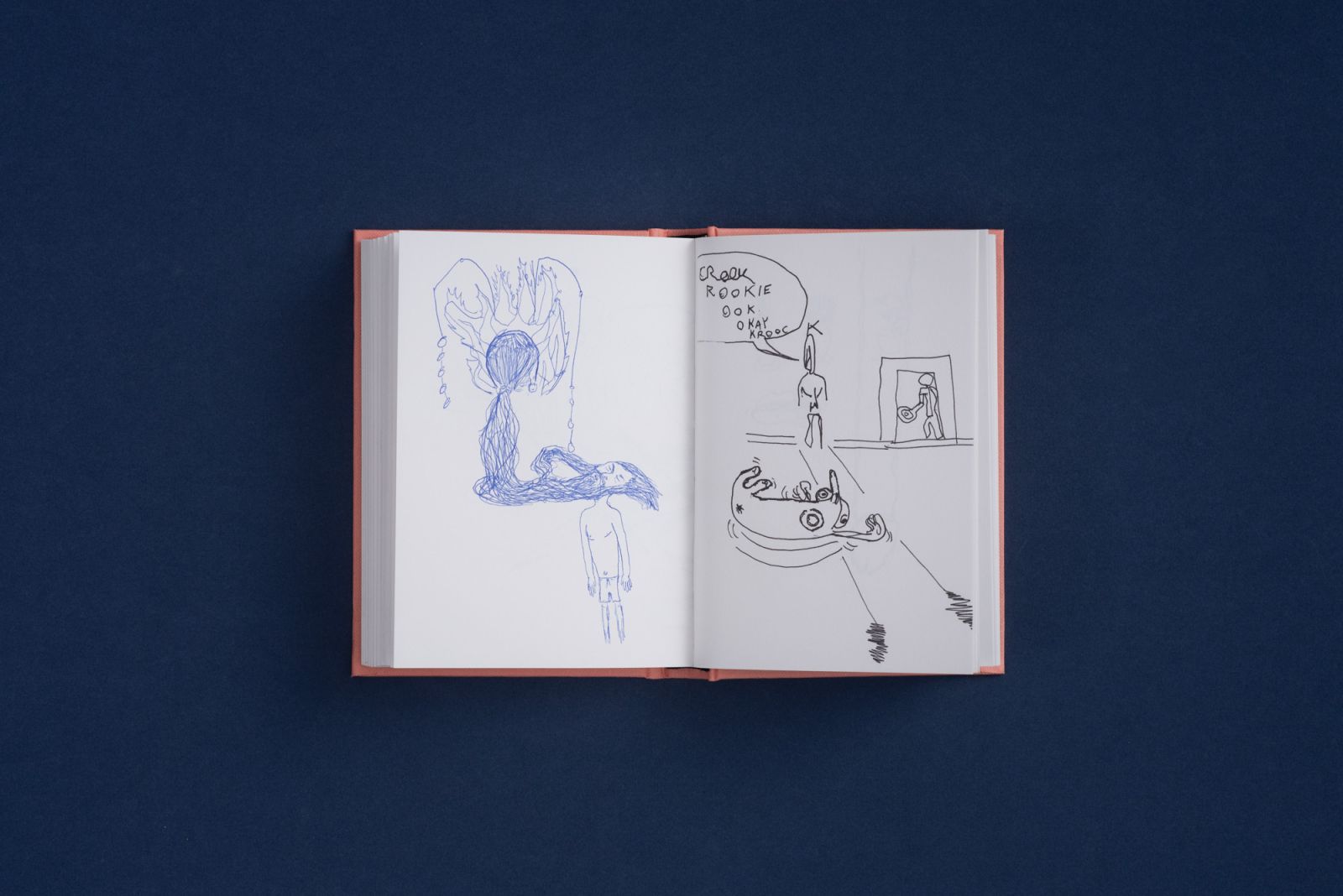

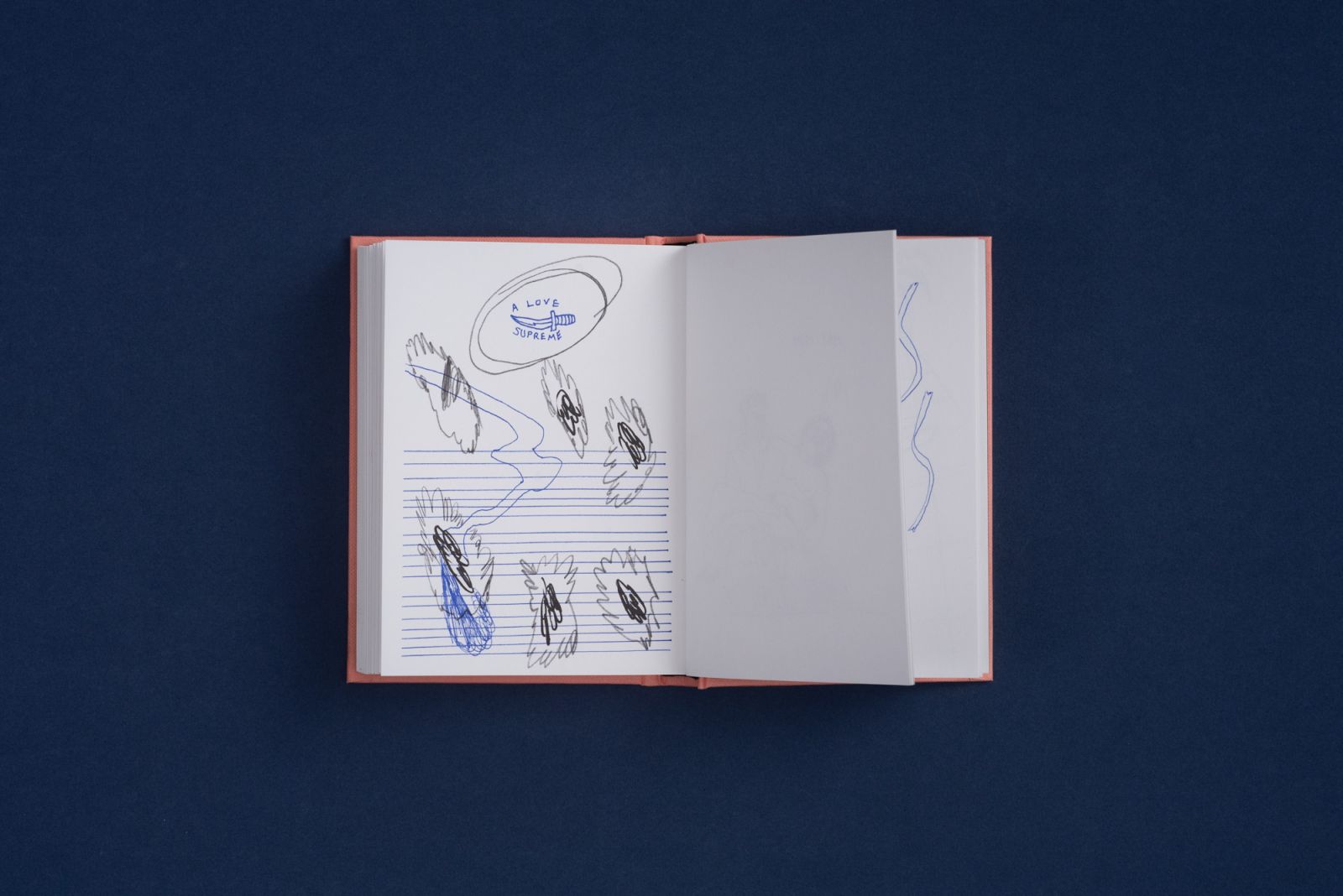

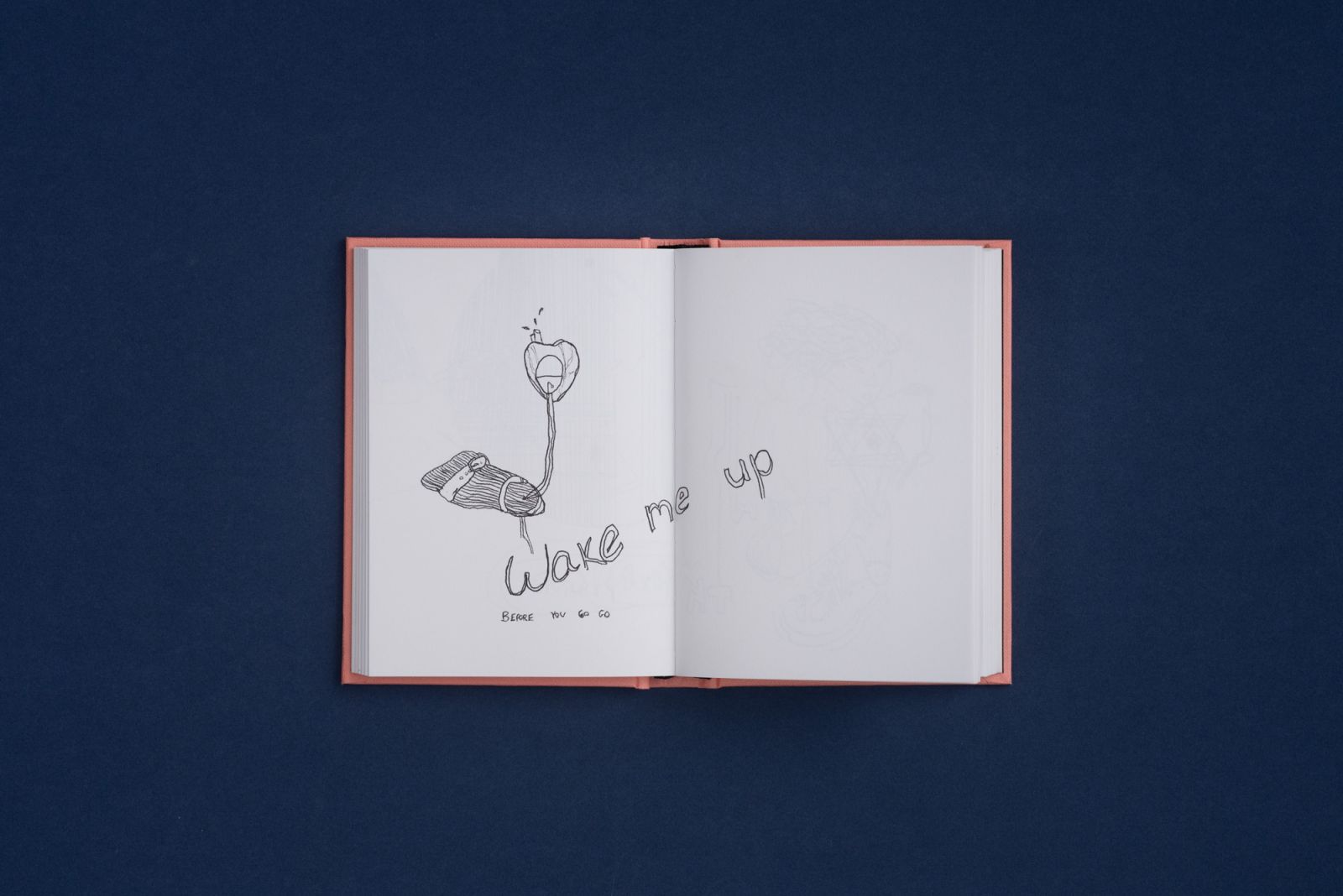

Each one of the drawings presented in the book touch on a personal, petty and lame aspect of life and my experience of it but the connecting tissue that holds them together is a sort of ugliness that offers a broader perspective on life. The title of the book is a sentence that originally appeared in a drawing I created that included a text. I have drawings that contain texts only, where it’s more important for me to envision how the words sit on the page. In the particular instance of the drawing that inspired the book’s title, its shape was deeply connected to the rhythm of the words and the physical appearance of the drawing on the page. More than anything it’s just a thought that popped into my head, a joke. I didn’t think it would become the title of the book, but eventually I realized it fit like a glove.

That’s the story behind the Hebrew title of the book. How did you come up with the English title? Did you feel that the Hebrew title would simply get lost in translation?

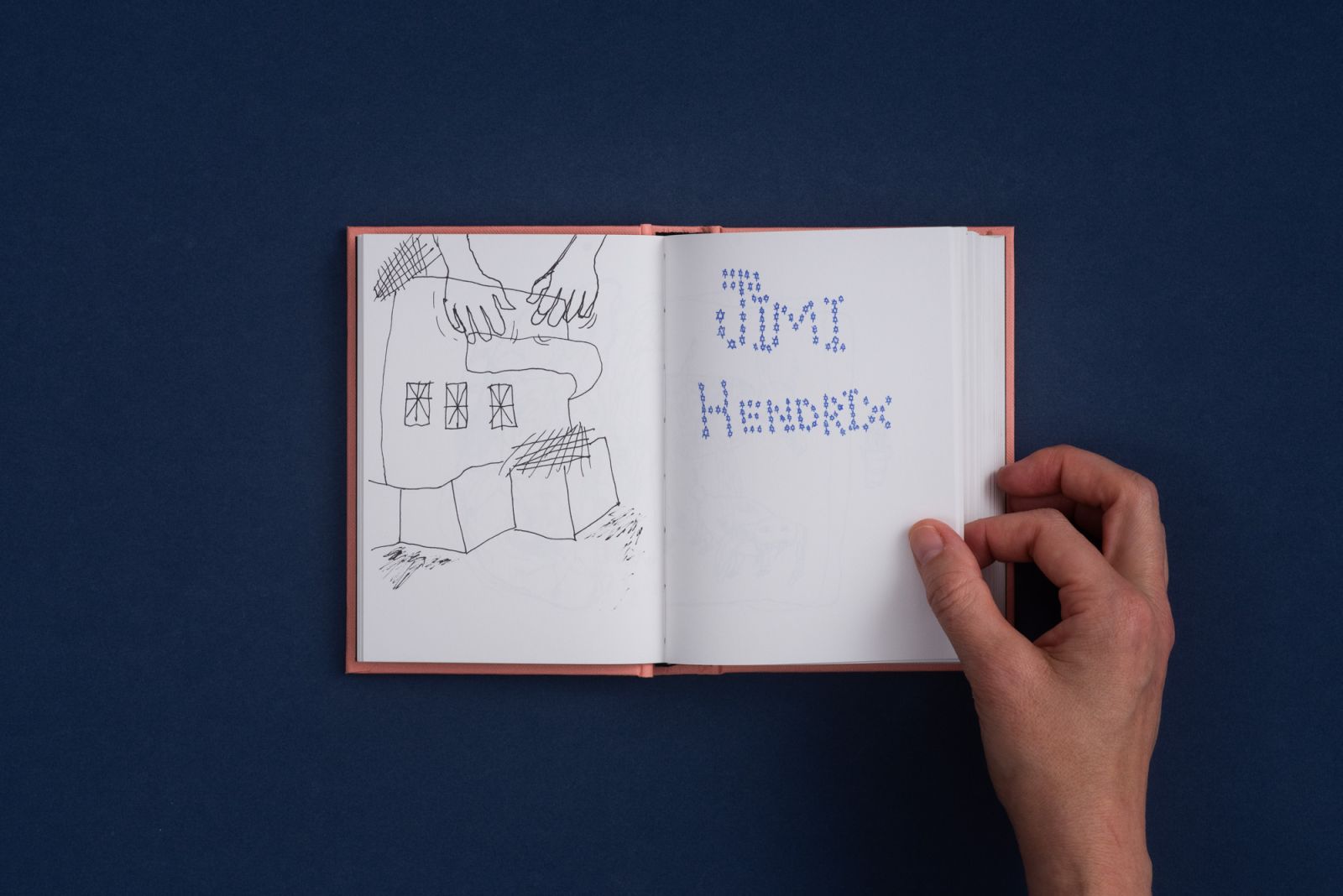

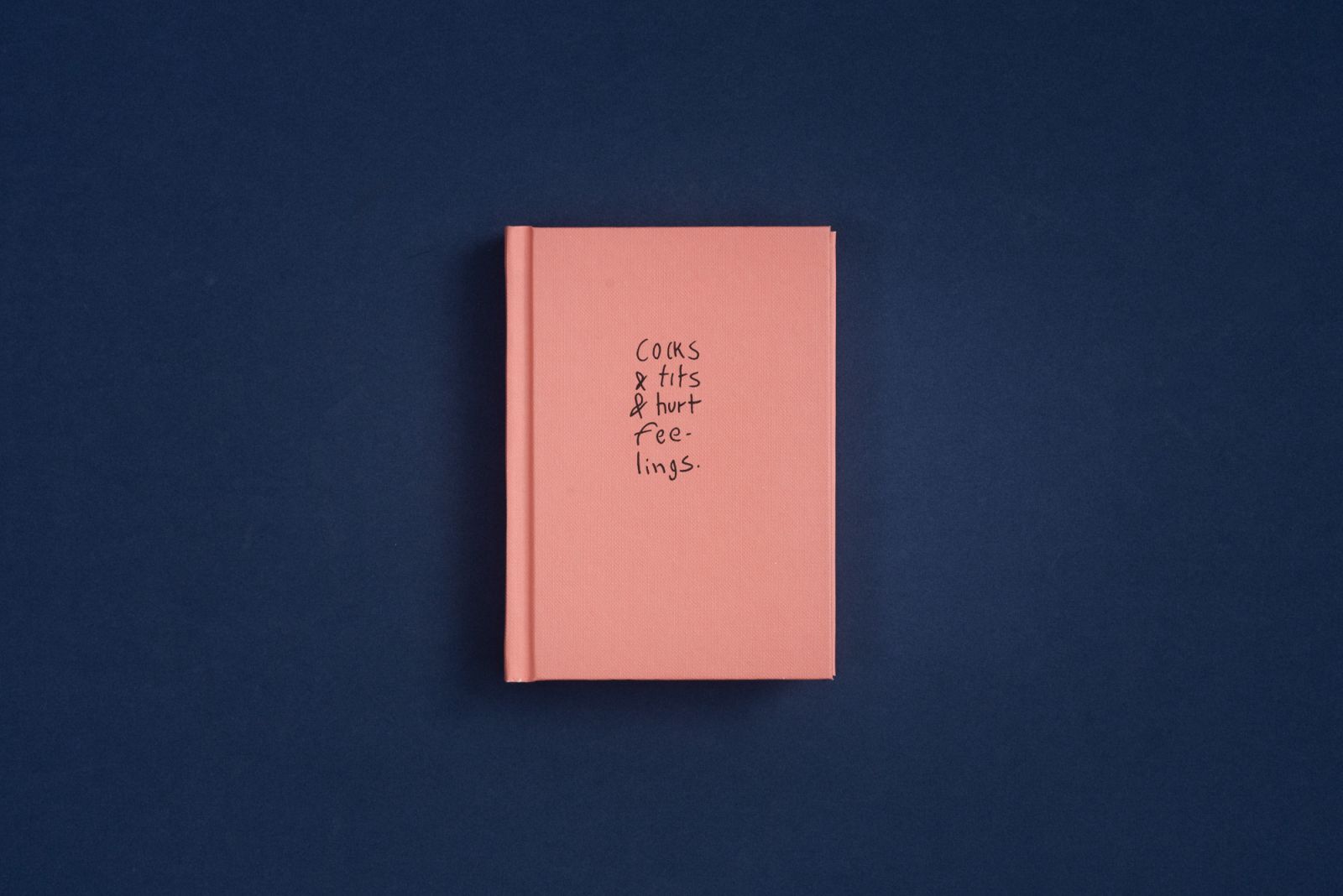

Inbal Strauss, who translated Doron Rabina’s text, offered her own translation for the title at the time but we knew that it didn’t work. It’s something we decided to mention in the English version of Rabina’s text. I had a drawing entitled ‘Cocks & tits & hurt feelings,’ and it referred to the wretchedness, the vulnerability and the sexuality that are recurring themes in this book.

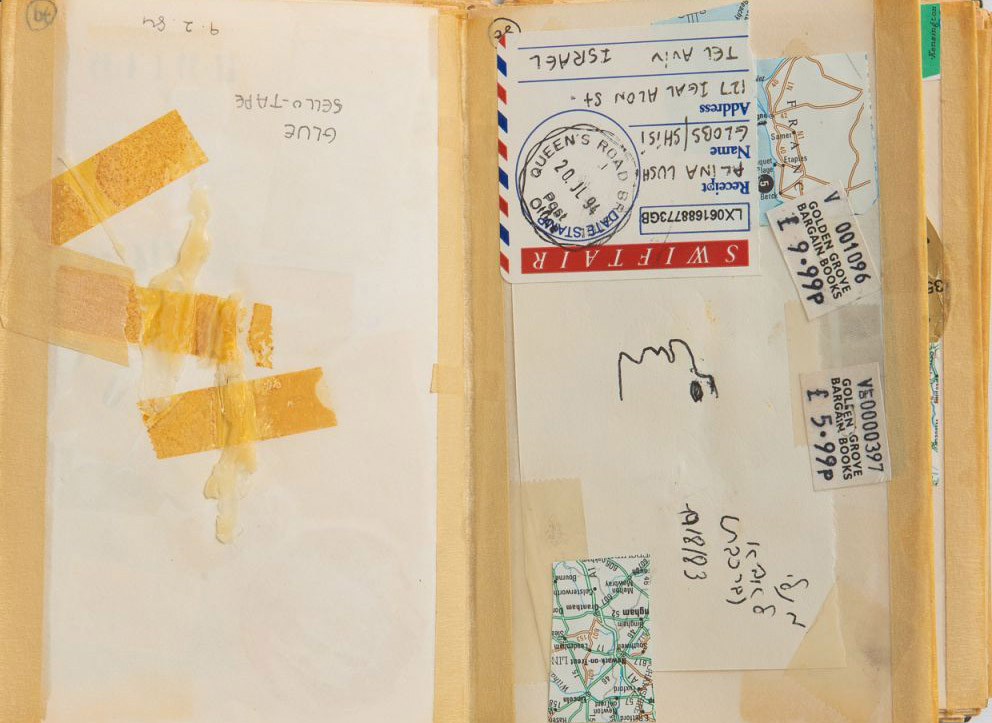

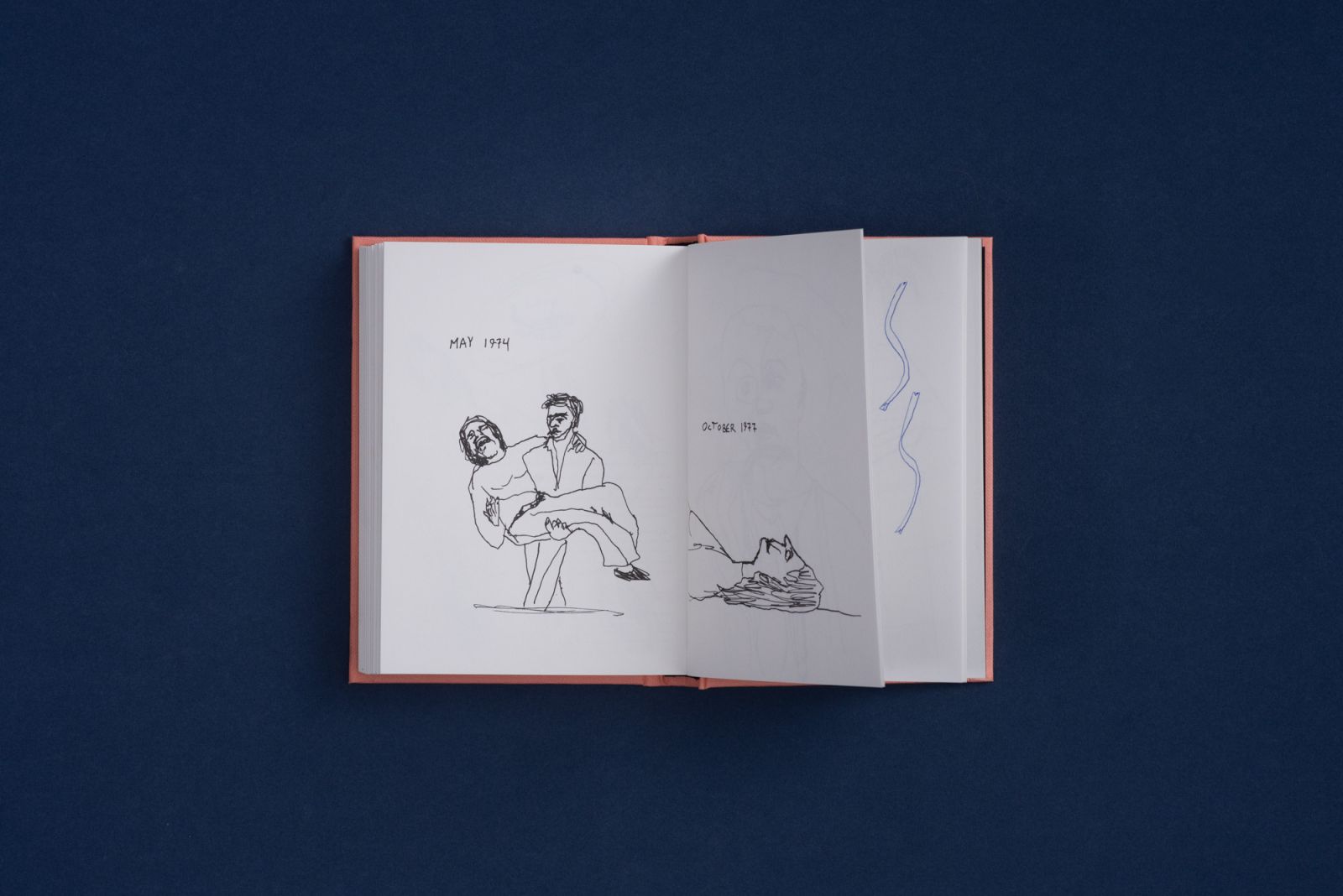

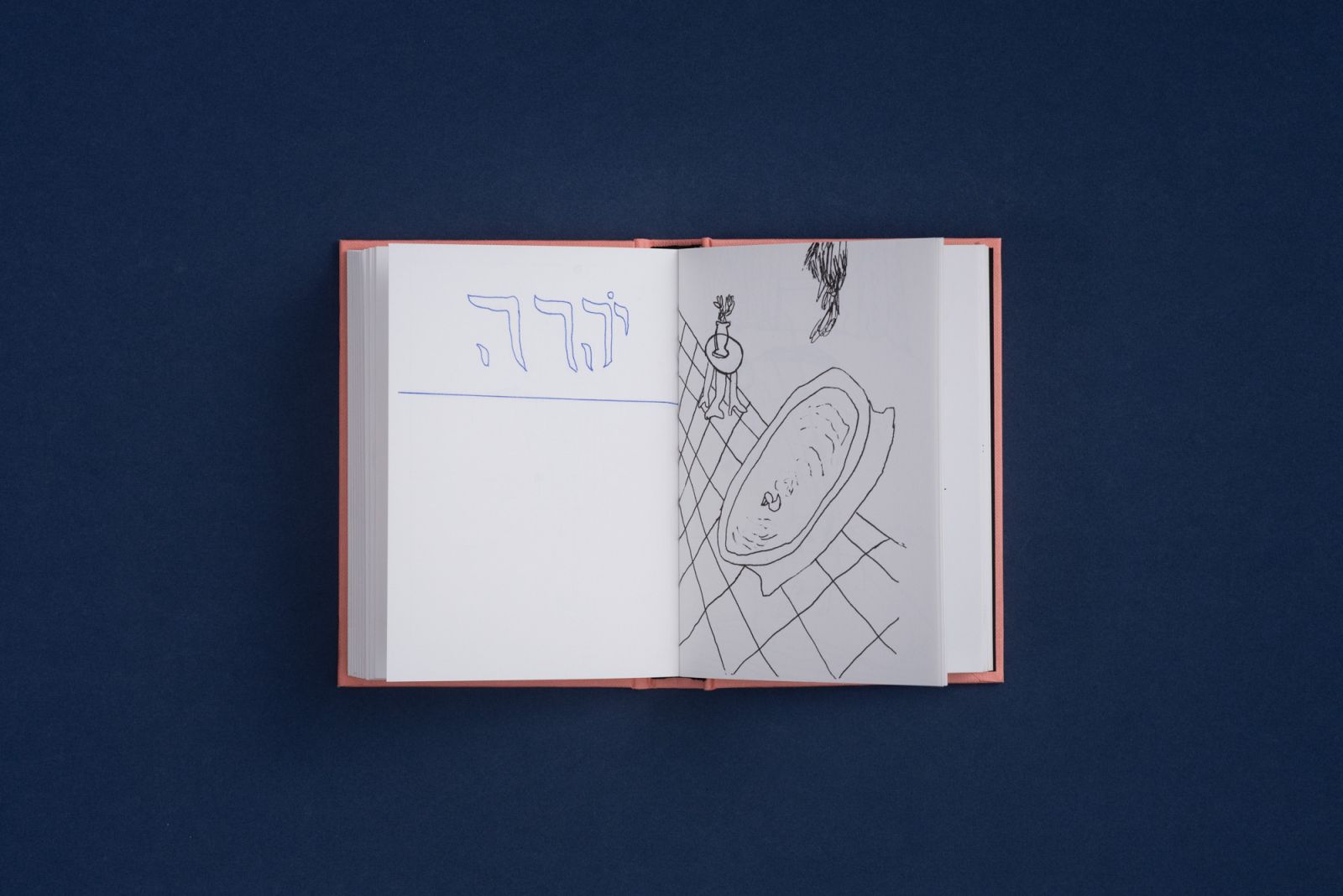

Choosing a different title in English had also provided me with an option I couldn’t possibly dream up when we started working on the book, which was to create two sides to it. The book can be leafed through from left to right or from right to left, depending on which cover you open first. This means you actually experience two books wrapped into one. The English version creates one visual sequence, the Hebrew version presents another, and then both sides converge in the middle. This opened up a whole new way of thinking and creating when we worked on the book, because I wasn’t busy asking myself how to create a linear visual flow anymore; instead, I was preoccupied with figuring out how to forge a meeting point between both sides. Had I stuck with a Hebrew title and an English translation, this dual experience the readers now have would never have materialized.

It’s interesting you should mention that, because I was thinking that the Hebrew title refers to some ideal or idea behind your works, while the English title refers to the formal aspect of the drawings and of the human body, whose amusing and exposed presence is a central topos in the works you are showing here. What was the work process like for you? It must have been a very different experience from creating a catalogue ahead of an exhibition, or working on a painting in your studio.

The late author David Foster Wallace wrote a book titled A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. I relate. I’d be hard pressed to say I want to repeat this adventure again. I wouldn’t exactly claim I suffered through it, but it was definitely a different kind of work from what I’m used to. Editing a book requires one to think and plan things in advance, which is the opposite of the process I try to initiate in my studio work.

This book includes drawings I created from 2002 to 2014, which demanded that I reduce the work and give up on featuring a lot of things. It was challenging and interesting, and I am fortunate to have been accompanied by Tirza Ben-Porat who designed the book, and who took on its production, which I certainly couldn’t handle. The book would not have been created if it weren’t for her, and she also helped me make decisions that really benefited from her outside perspective.

The size of the book is also an issue worth discussing. You created a pocket-book, the size of it replicates for the reader your experience of working with a sketchbook. The size of the book also seems like a nod to the character of the works it features, drawings that were relevant to certain moments and places in your life and appear to be the visual manifestation of an impulsive, perhaps even reflexive physical gesture.

You’re right. The one thing that was clear to me from the start was that I wanted the book to be something you could carry in your pocket, which had been the case with most of the sketchbooks I had throughout the years. I also wanted the reader to feel like a Peeping Tom, almost as though he or she had accidentally opened my personal sketchbook. I was going for a visual experience that ranges between the contentedness of leafing through one’s own private contents and the pleasurable shame one might feel upon stealing their sibling’s journal and reading it in secret.

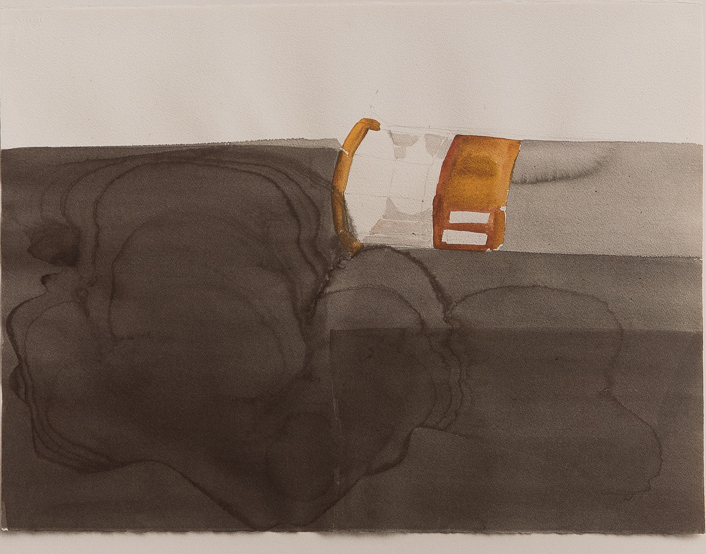

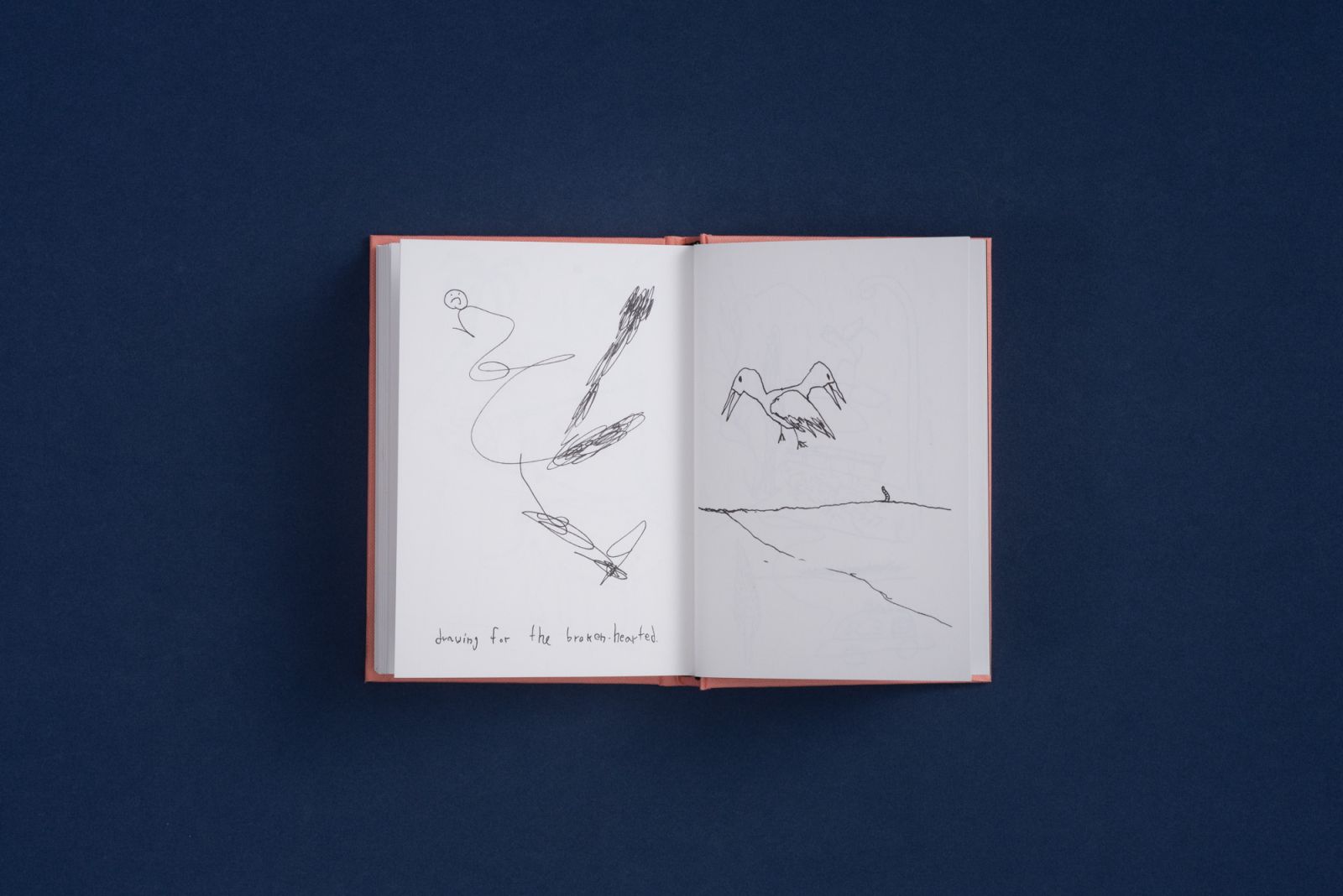

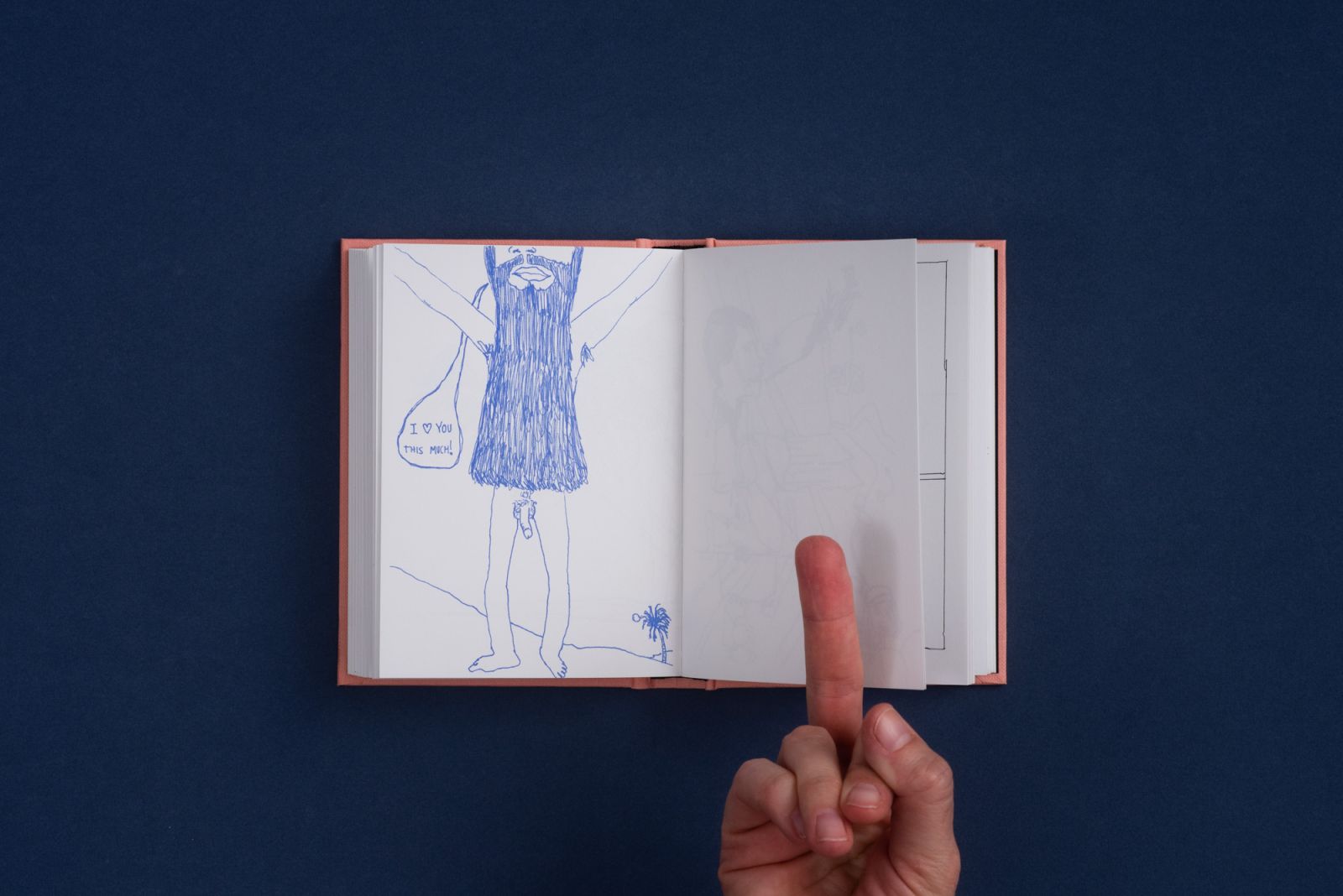

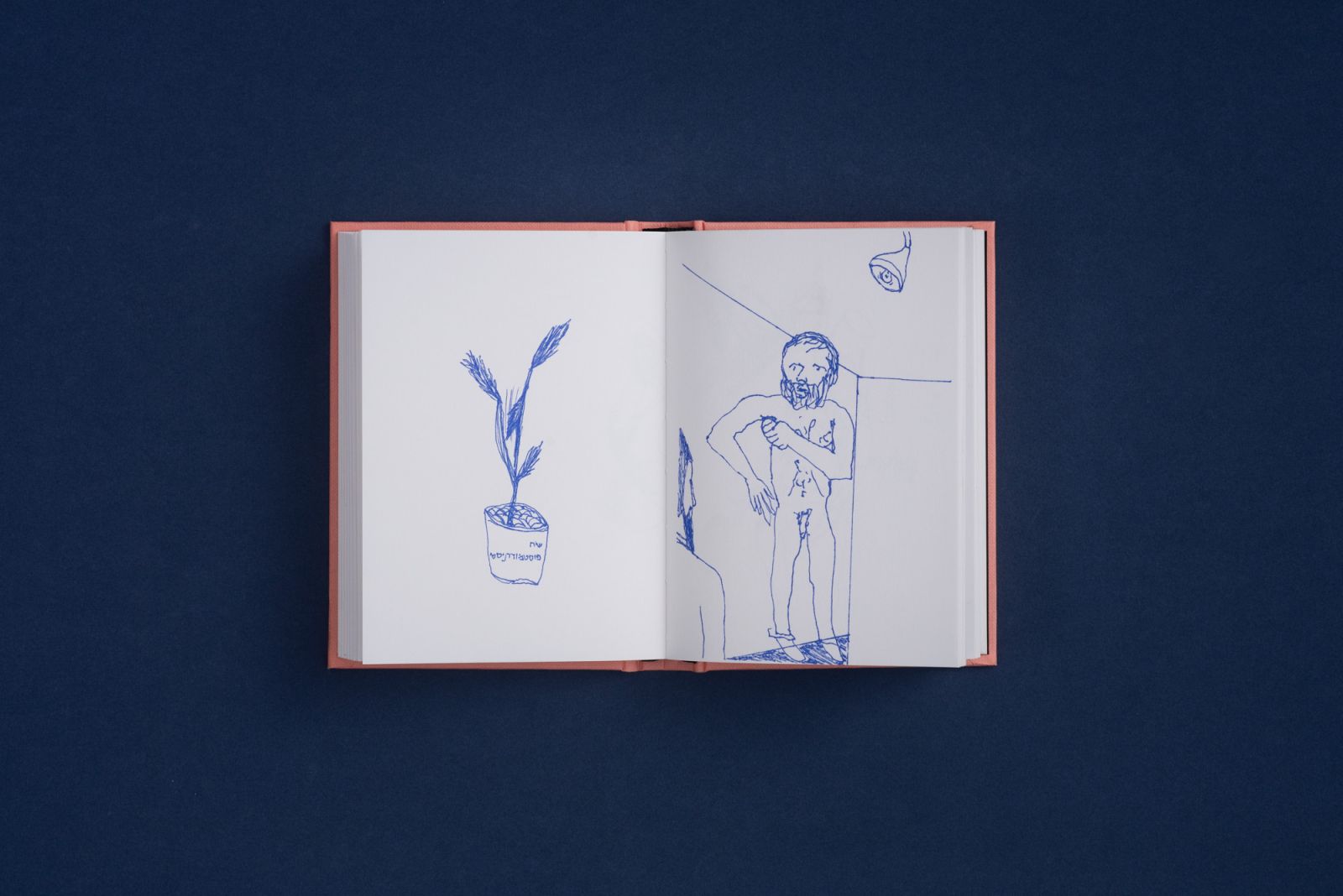

I’d like to point out that the protagonist of this artist book is the human body. In your paintings the body is present and absent at once, a kind of object whose mere appearance hints that it will soon disappear. But it seems that in your drawings the body is a practical tool that you use. Self portraits, portraits of others, hands that are extended forward from a void, dismembered body parts—all appear to serve you in your creation of a very corporeal visual dialect. How do you experience the presence of the body in your drawings?

In my drawings, I acknowledge the human body in all of its frailty, vulnerability, absurdness and flaws. The body is a central figure in my work. On the other hand, because of the nature of my work in the medium of drawing—which is linear and minimalistic—the body always appears as a sort of marking. I expose my guts to the viewers, even though technically speaking, the guts are an empty space in this case. You see the hollowed-out innards.

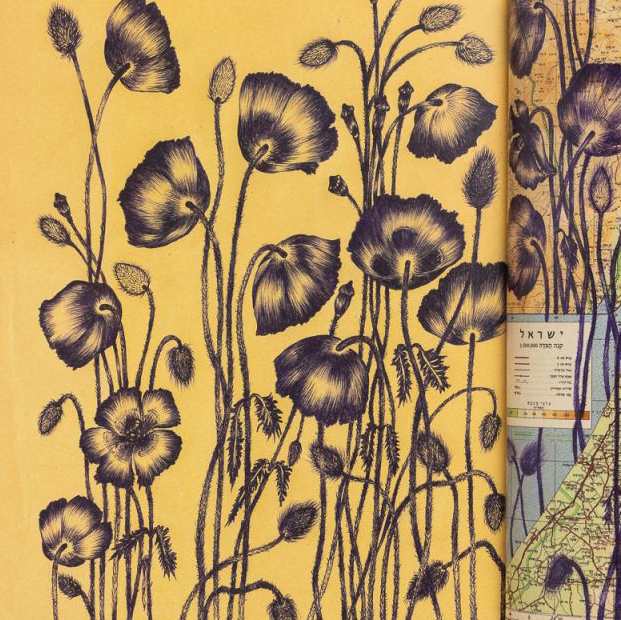

You have stressed to me in previous conversations the importance of color in your artistic practice. As a painter, colors and your duet with them are such a dominant part of your work. But in this book you reveal drawings that are quite minimalistic and whose only colors are blue and black. Did you have any trepidations before you decided to reveal a body of work whose visual language is opposed to the work you have shown throughout the years?

Of course. I constantly think about this gap. But maybe it is worth mentioning that I have presented my drawings before in a solo exhibition at the Darom Gallery, a Tel Aviv space that was established by Eran Nave, Tamir Lichtenberg and Yaron Attar, and which has since closed. The starting point for that exhibition was a long wall covered in drawings.

Having said that, I did always feel that the format that fit best these drawings wasn’t an exhibition but rather a book. I drew long before I started painting, even before I realized I was a painter. In the first two years of my BFA studies at Bezalel, all I did was draw. There is something about working with a sketchbook that is very initial, association-driven and devoid of self-criticism because it’s such an instinctive action. The critique only comes later, when you take a second look at your own work and try to decide which parts of it are meaningful. My sketches were never intended to become drawings, they were creations in and of themselves—whether I thought it was nonsense or actually decided it worth showing. Nonetheless, I believe that my drawings and my paintings share the same visual DNA, which has to do with my individual gaze at some existential catastrophe. At the end of the day, the way I see it is that the drawings exist in a parallel universe, where the abundance of color that exists in paintings is replaced with something that is more immediate, concrete and very literal.

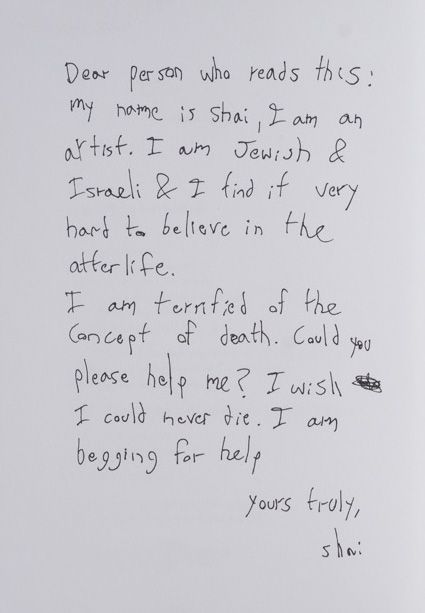

If one doesn’t delve deep into your drawings, one might get an impression that those are lighter and more comic works. I always open books from left to right, because English is my mother tongue. That’s how I opened your book, so I encountered the existential drama you refer to right on the first page, which is the last if you choose to read the book from right to left.

That first page feels kind of like the gun being fired in the first act. You write an address aimed at the readers in which you announce yourself to be an artist, a Jew, an Israeli and a man who does not believe in the idea of an afterlife. Then you admit that you’re terrified by the notion of death, and beg the readers to save you. This text is accompanied by a grotesque drawing of a bending figure that seems to be masturbating. Is that how you want to present yourself to the world? What a pleasant introduction.

That’s interesting, I didn’t remember that I presented myself in that order. Like you say, I thought that if someone leafed through my book he or she will have an uplifting and perhaps occasionally funny experience, and they wouldn’t think that they will suddenly be made to read a letter from someone asking for help in figuring out how to understand and cope with the drama of life and death. If the reader unfortunately happens to be a native English speaker like yourself, then that’s the very first thing they encounter. But hey, in my defense I can say that it only gets better from there!

Maybe that’s what my drawings and my paintings have in common… I can’t really dive into the dark depths without adding a certain wink, or a tongue-in-cheek remark. It’s not even a defense mechanism, it’s just part of my panic over life and this world.

Your humor is your protective shield.

No, it’s just inherent to everything I experience, see and feel about the world. Life is pathetic, and pathetic also means funny. I want to point out those things that everyone thinks about and fears, but I try to phrase it kind of like: "I know there’s something you’re hiding from me, and I’d like to know what that is. Please help me if you can."

That specific text you’re referring to is part of a series of letters I had written to all sorts of addressees. In an exhibition titled Sweatshops (Gallery Contemporary, 2011. Curator: Ohad Matalon), I presented a text work that faced the display window of the gallery. It was a letter addressed generally to curators or gallerists from overseas, in which I begged them to take me and I wrote that I would even be willing to babysit their kids and sleep on their couches. I wrote that here in Israel it’s horrible, too hot and too many camels, so I would love their help in getting out of here and presenting my work elsewhere.

The format of letter-writing has been part of my practice for a while. I think that the letter featured in the book is the first one of that series, and perhaps the most sincere of all of my letters. Despite the irony of the words, I really wear my heart on my sleeve there. It’s a painfully honest letter. And pain matters to me in this book.

It’s worthwhile considering the significant space language takes up in your book as opposed to the important but subtler role it plays in your drawings. Your use of written language in some of the drawings is completely ornamental and humoristic, whereas in other works your writing is intimate and it’s almost tempting to read it as confessions from a personal journal or a visual memoir. How would you define your use of language in this book? Is it more comical or revelatory?

I would say that in my paintings, language functions as a kind of cogwheel that sets things in motion, whereas in my drawings the language or the texts are the very pulsing heart of it all. I think that honesty is a misleading phenomenon which can be interpreted in many ways. I am a very honest man, unless I am not being honest with myself. I didn’t add anything to this book, I didn’t prepare drawings especially for the book but rather chose to show creations that were born out of a very instinctive dialogue with myself. Unlike my process when I paint, I didn’t contemplate viewers at all while creating these drawings. That is why the book can look and feel like a very vulnerable and fragile object, and at the same time seem like a theater of absurd unraveling between the pages. I think that’s what makes it all work. It’s also how I am in life… I can’t really think about the world without snickering a little. How very Jewish of me.

So now I get why “Jewish” is the second adjective you use to define yourself in that letter. To cap off our talk, please complete the following sentence: Creating a book is like…

To be honest, I’d have to say that it’s quite like nothing else I have ever done.

Which book should we add to our library next?

Working on a Computer, Sharon Fadida’s artist book. It’s amazing. I really cherish the copy I have at home.

Where can readers get a copy of your book?

On my website, at Hamigdalor bookstore, at the Bookworm bookstore, at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, at Little Paper Planes, Topics, Bookart Bookshop and at Printed Matter.

Shai Yehezkelli (b. 1979) is an artist who lives and works in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel. He attained both his BFA and his MFA from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design’s Fine Arts Department. Yehezkelli’s works are inspired by the traditions of local painting, while seeking to absolve them of their sublime aspect and instead highlighting their connection to the everyday and the banal. In his paintings, Yehezkelli uses complex iconography, through which he explores elements of Israeli history and identity –while deconstructing the holiness and seriousness with which national narratives are usually created and regarded.

Yehezkelli is the recipient of the Rapaport Prize for Young Israeli Artist (2015). Yehezkelli presented his works in numerous solo and group exhibitions; in 2021, he showcased a solo exhibition at the Beit Uri and Rami Nehushtan Museum, Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov.

״I wanted the overall contents of the book to create a stirring and explosive impression or to offer a macro viewpoint of the world.״

״I wanted the book to be something you could carry in your pocket, which had been the case with most of the sketchbooks I had throughout the years. I also wanted the reader to feel like a Peeping Tom, almost as though he or she had accidentally opened my personal sketchbook.״

״I can’t really dive into the dark depths without adding a certain wink, or a tongue-in-cheek remark. It’s not even a defense mechanism, it’s just part of my panic over life and this world.״