What’s your attraction to Virginia Woolf’s book To the Lighthouse?

I have been both attracted to and repelled by To the Lighthouse for a few decades. The book was published in Hebrew by Meir Wieseltier in the 1970s (Sifrei siman kri’ah Publishers, 1975), and in a second Hebrew edition translated by Lia Nirgad (Penn Publishing, Yedioth Books, 2009). Over the years, I read the book several times in both translations. I would stop after a few pages—I was both attracted to it and couldn’t bear it. You’re asking about attraction and I think part of the power of this novel lies in the fact that it deals with the power of attraction; the sweeping power of the sea, the magnetizing power of the lighthouse, the forces exerted by the novel’s protagonists on one other, holding on to each other. A powerful mysterious experience. This is, of course, Virginia Woolf’s marvelous writing, which captures movement and remnants of thoughts and sensations, rooted in an experience of human alienation and a longing for intimacy. It’s surprising, sensitive, bold and wild writing, which Wieseltier’s wonderful Hebrew translation adds to. I created the works between the years 2013 and 2015, and my book came out only in 2020.

What does the book’s addressee, Mrs. Ramsay, mean to you? Why did you dedicate the drawings to her?

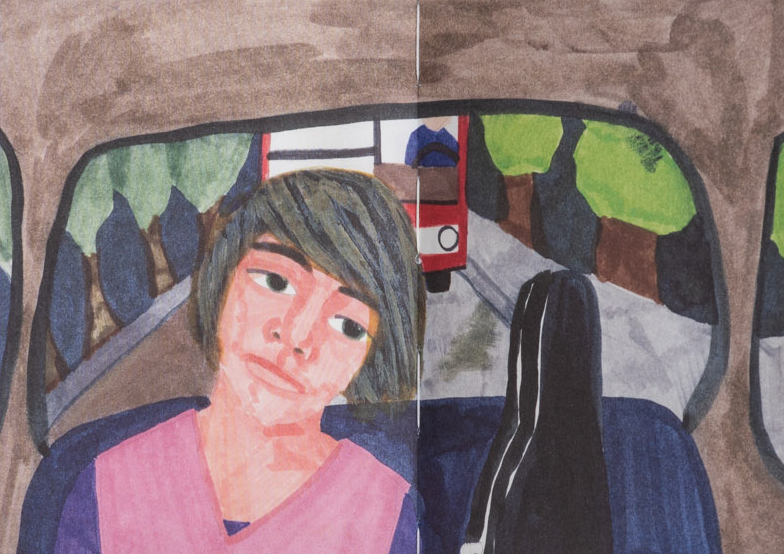

The book was created following an exhibition in which these works were displayed, at the Israeli Art Gallery at the Tivon Memorial Center, curated by Tali Cohen Garbuz. When Tali approached me, I immediately suggested that I work on To the Lighthouse. I started drawing as a kind of “reading testimony”; I drew from an initial encounter with the text and an attentiveness to what it evoked. I ended up referring to the first part of the novel, “The Window.” Ultimately, in most of the drawings, I gave expression to the character of Mrs. Ramsay, the matriarch. I could identify with her, with the desire to maintain and hold on to the home, to watch over the family, and at the same time, I felt the moments of silence, limpness and weakness. I felt like I knew her. Tali suggested the title of the exhibition, which became the title of the book. The drawings are addressed to her, to Mrs. Ramsay. I am sometimes also Mrs. Ramsay, so they’re also directed towards me.

It’s as Woolf writes: “The passage to that fabled land where our brightest hopes are extinguished, our frail barks founder in the darkness, … one that needs above all, courage, truth and the power to endure.” Who accompanied you on this journey to the book?

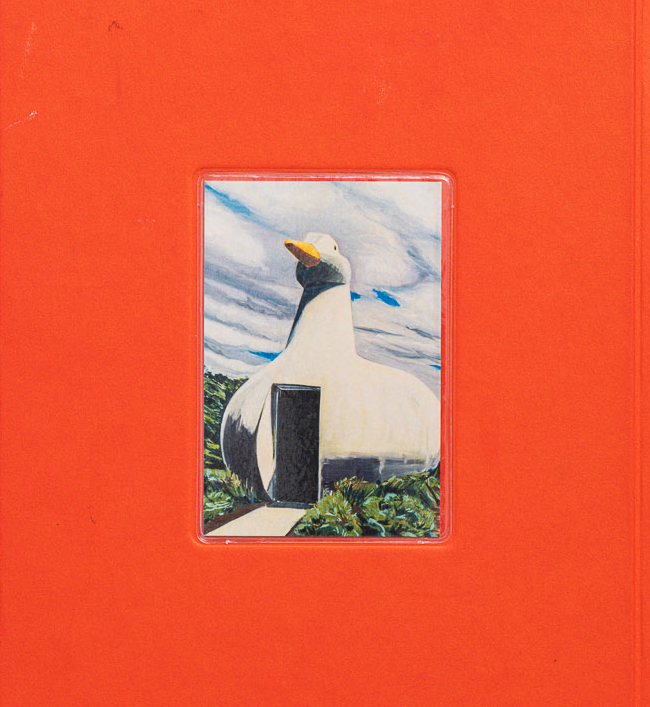

Even before the book, Tali accompanied the drawings with sensitivity and wisdom. Michal Ben-Naftali came up with the idea for the book when she was at the exhibition. At the time, she was editing a series of books and was thinking of including the book in the series. The series was paused but Michal continued to accompany the book, offering her writing, which is very precious to me, and connected me with Michael Gordon, the book's graphic designer and producer. Michael understood the drawings and knew how to bring them to print in a way that would complement them. He insisted on scans, understood the format, the colorfulness of the cover. He dove into the depths of Michal’s text and understood the relationship between the text and the images. He knew how to give the book its character. It took five years from the end of the exhibition in 2015 until it was printed. Things demanded their time. To my delight, Merav Shaul of Asia Publishing responded to my request, and received the book very generously.

In Michal Ben-Naftali’s excellent text, she quotes you as saying: “Woolf was an anchor for my transformation.” So how did the transformation happen? How do you “transfer states of consciousness to painting”?

Yes. Michal’s text is beautiful, and I understood more about Virginia Woolf and my drawings because of it. Based on a reading of the first pages of the novel, the drama unfolds: a boy who wants to sail to the lighthouse, a mother who protects the child, a father who objects to the journey, and outside, the painter Lily Briscoe, trying to paint a portrait of the mother and the son through the window. In the book, the stream of consciousness follows the constant and changing formation of consciousness, just as I am aware of the formation of things during painting. Images and stains, memories, come up, whether consciously or not. Attention turns to the transition between the internal occurrence of mental materials that emerge even before the painting, and their formation during the painting, when they receive material expression. This is an important transformation. For me it is one of the crucial moments in painting. There will always be a gap, there will always be a difference, there will be a surplus or a shortfall. This is where the transformation takes place. Since what grabbed me in Woolf’s writing is her ability to trace the transformation of consciousness, I’m most attentive to capturing this possibility by the pictorial act on paper.

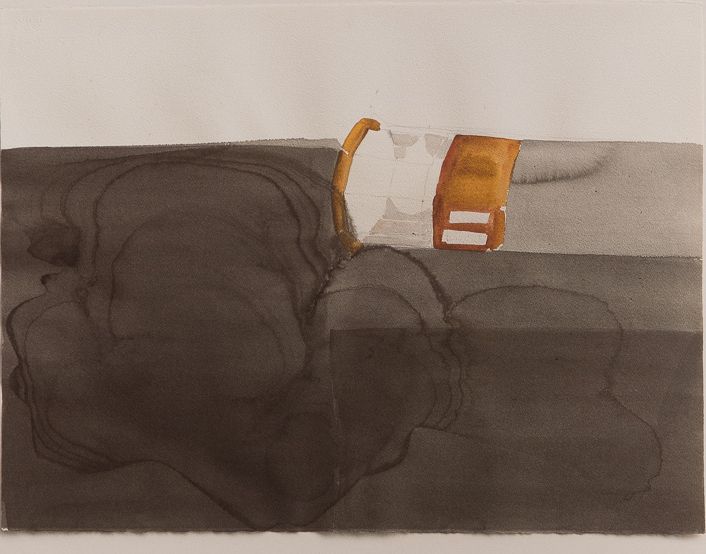

It seems that your choice of ink, pencil and watercolor is not accidental. The late Naama Tzel wrote: “In To the Lighthouse Woolf places her articulation between the sea and the land ... the movement back and forth from the fluidity and dissipation of the description, to momentary solidification and back, will become decisive in her next novel [The Waves, 1931]” (“Nothing is just one thing, ‘To the Lighthouse,’” Haaretz, 2009). Like Woolf, you created a visual language here that manages to be both vague and sharp.

Thank you for mentioning the late Naama Tzel. I loved her book Simi rosh (Afik Publishing, 2020) so much. As for the ink and watercolors, I guess they do the job. It’s a journey with liquid substances. Lots of preoccupation with control and lack of control, and matter has its own will. I practice estimating the amount of ink. I think in terms of weight and energy. I experience the weight of the stain relative to the contents it carries, estimating the amount of water the stain can carry. The stain changes as it dries. It carries its secrets, and the work of deciphering the stain is significant. If you will, it exists between my unconscious and the stain’s unconscious. Alongside the slow time of drying and setting the impressions, there’s also a sharp action, as you said. This is an act of marking. I’m required not to chat, to be resolute, decisive and quick. It’s clear to me that in the psychoanalytic space, I’m allowed to manifest these processes, and I am very grateful for this.

I’d like to take a moment to quote a sentence from Woolf’s To the Lighthouse that seems to me to have particularly affected you: “To such people even in earliest childhood any turn in the wheel of sensation has the power to crystallize and transfix the moment upon which its gloom or radiance rests…” The wheel of sensation is repeated throughout the book in a variety of instances.

Wheels, saws, gears. I’m attracted to the mechanical world, to machines, to hardware stores. It’s strange to talk about mental movement from mechanical images. This is probably also the rotational motion I connected with. Some drawings show an image of a screw from a meat grinder. I thought of the grinding operation in the context of the role of the mother processing material for her child that can’t be digested by him. By doing so, she allows him to process, digest, and transform, to turn incomprehensible components into meaningful ones, a thought drawn from psychoanalyst Wilfred Bionn. Later, I saw that cogwheels are experienced as something intrusive and aggressive; that’s definitely another possibility.

The researcher Ela Krieger, who deals with the relationship between painting and print, suggests seeing the image of the wheels in the series as the outcome of your ongoing work with printmaking. Is that a statement that resonates with you?

In work with engraving in parallel to painting. It's a medium that requires the mechanical work of rotating an extruder to transfer a pictorial image from a metal plate to paper. I like her suggestion, to see the gears as images that represent the physical act of pressing. This is because there’s an affinity between corporeal, physical action, and mental movement.

Would you please explain the bright pink color that appears in quite a few of the drawings.

In the 1990s, I worked a lot with shades of red, maybe it’s a remnant of that. I just love this pink. I guess it aerates the series and allows it to breathe. After I closed the book, it stayed with me like sediment in the sea.

Apropos the sea, we must of course mention the blue cover, which reminds of the sea, and of cyanotypes, which are themselves a kind of sediment, of objects and light.

When Michael Gordon suggested the color, I knew it was right. This beautiful turquoise corresponds with the cover of the 1975 edition of To the Lighthouse, but it also has a very personal connection—a story about a coat. In the 1960s, I lived in Haifa, in a beautiful neighborhood in the Carmel Mountains, and even so, back then clothes were handed down. Buying new clothing was a very festive affair. For a whole year, my parents planned to buy my sister a coat, and after they had completed their research, the whole family went on a trip to the "Bambi" store in the Carmel. I was nine years old, and hard as I tried, I couldn’t take my eyes off a bright turquoise-colored coat, with the visible lining that had the word Ski on it. I stood with a stinging throat and a clenched body. My mother came up to me and asked, “Dorit, which coat do you want?” I remember only a few sentences in Polish that were exchanged between my parents, and my mother taking the turquoise coat off the hanger, helping me slip my arms through it. How I loved that turquoise that enveloped me for several winters.

You have created a kind of babushka doll here. Woolf writes the painting through the figure of Lily Briscoe, you draw the words, Ben-Naftali writes about the drawing of the words. All this wraps itself around this truly rare novel.

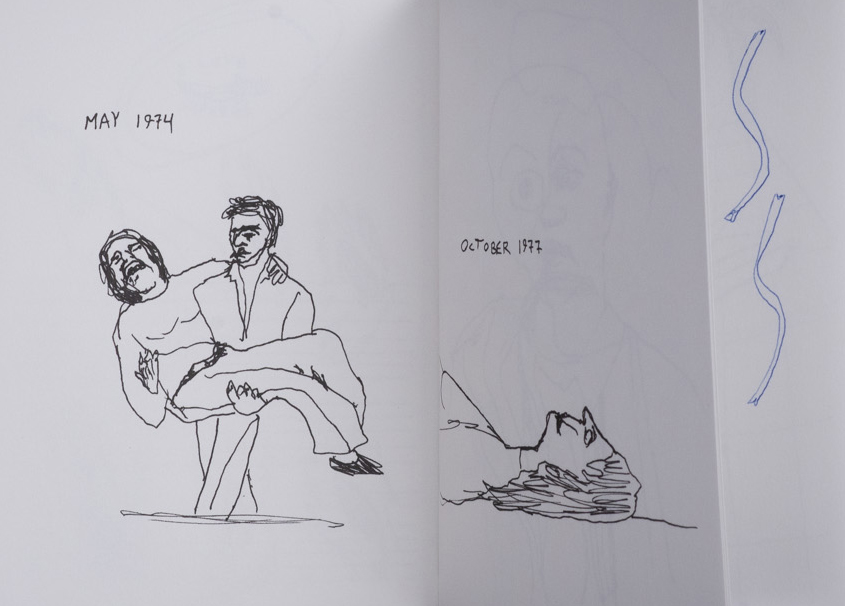

What you’re proposing is wonderful. Thank you. When I was drawing, I didn’t put Lily in the works as a presence. Michal gave her plenty of room in her text and actually, I think that by doing so she gave the babushka depth. Scanned pages from the original book, which were inserted at the end of the book following pleas from Michael Gordon, also created a circularity.

Perhaps it’s not by chance that the last line in your book is: “For he wished, she knew, to protect her.”

How interesting. I wasn’t aware of that. The choice of scanning certain pages from my personal copy of To the Lighthouse flowed consciously from a desire to bring some context to the paintings, to allow for a study of Woolf’s writing, as well as of my pencil marks, a sort of layout of a work diary. What became clear in retrospect is that in the selected passages, there are descriptions that didn’t get pictorial treatment, and it’s precisely these that at times embody an invitation of reconciliation, of consolation.

Are the characters from the book still with you?

They’re like witnesses who keep talking. They are part of me on a daily basis. The figure of the father riding a horse, likening himself to a soldier on a battlefield, or to the head of an expedition off to conquer a mountaintop, crosses the grass where Lily is painting. A strange, theatrical performance, like entering a stage. Sometimes they speak to me, “You didn’t pay enough attention to my humor, you didn’t articulate my childishness, you didn’t give enough space to my pain.”

How does it feel now that the book has been published and is out in the world?

When the book came out, I loved it but also felt embarrassed. I felt exposed and naked. The coronavirus unexpectedly allowed me to get used to it before it was distributed. The book was published during the third lockdown; the boxes arrived at home, and the stores and everything were closed. I left the boxes closed until the stores opened, and slowly, occasionally shared the book with someone close to me; I let it seep in. Now that the book is out in the world, a dialogue about it is possible.

What do you make of the last line of To the Lighthouse: “It was done; it was finished. Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.”

The last sentence refers to the painter, Lily, who at the beginning of the novel stands on the grass with a painting easel, struggling in vain with demons and destructive voices, as she tries to paint Mrs. Ramsay and her son. Ten years later, at the end of World War I, after the death of Mrs. Ramsay, the family returns to the abandoned house, to make good on the promise of sailing to the lighthouse. Lily again situates herself in the same place on the grass, struggling with the feeling that things aren’t on time, that she isn’t suitable, again destructive voices rise up, Mrs. Ramsay’s spirit, as if demanding her place from her and taking over the space. Only at the end of the day does Lily experience the moment when she can grasp the exposed thing, the thing itself and translate it into a painting. Woolf describes it this way: “But what she wished to get hold of was that very jar on the nerves, the thing itself before it has been made anything.” This is her vision, clean, no longer Mrs. Ramsay’s hovering spirit, the painting responds to the present moment, afresh. Lily allows herself to be, meaning she owns herself; she belongs to herself.

What book should we add next to our library?

Dictionary by Asnat Austerlitz, published by Asia Publishers. A beautiful artist's book, with minimalist and restrained language created from computer-generated works printed for the book.

Where can we get a copy of your book?

At the Asia Publishing House, at HaMigdalor, Sipur Pashut, and Tola’at Sfarim bookstores in Tel Aviv and in all independent bookstores.

Dorit Ringert, born in 1956, lives and works in Givat Ela. She holds a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem and an MA in Art History from Tel Aviv University. Ringert creates works on paper in ink, pencil, watercolor and engraving that relate to the connection between psychoanalytic thought and visual art. She is a lecturer at the Art Institute at Oranim Academic College of Education and an interdisciplinary fellow at the Tel Aviv Institute for Contemporary Psychoanalysis.

"Ultimately, in most of the drawings, I gave expression to the character of Mrs. Ramsay, the matriarch. I could identify with her, with the desire to maintain and hold on to the home, to watch over the family, and at the same time, I felt the moments of silence, limpness and weakness. I felt like I knew her."

"I experience the weight of the stain relative to the contents it carries, estimating the amount of water the stain can carry. The stain changes as it dries. It carries its secrets, and the work of deciphering the stain is significant. If you will, it exists between my unconscious and the stain’s unconscious."