It’s a challenge to talk about two books at the same time. It clarifies the dual aspect of your work, and maybe it’s a good prism to start the conversation with. You are undoubtedly an artist who makes books, and also teaches a course on making books at Bezalel and WIZO Haifa. Your first book, which you self-published, is called Day Night, and is made up of two parts: you dedicated Night to your late mother Bianca Eshel-Gershuni, and Day to your late father Moshe Gershuni. The two books we’re discussing are also a two-pronged journey: one is a physical photographic journey in the English village of Lacock, where the British inventor of photography Henry Fox Talbot worked, and the other is a virtual journey in the same village, which you do using a computer screen and Google cameras. Perhaps in the spirit of the opening of Yesterday’s Sun, it’s better to start from the end. Who did you dedicate the two books to?

I dedicated Yesterday’s Sun to Talbot himself, but on a deeper level, I can say that it’s also dedicated to my father, because the project is mostly about the father figure. I went to “meet” Talbot at a very critical stage in my relationship with my father, when I was conscious of the time that was running out. He was very ill then. And that awareness, of finiteness, led me to embark on this journey as a kind of preparation for parting. I went to meet in order to say goodbye.

It’s interesting when I think about it now for the first time: I arrived in the village at the blue hour, at twilight. Talbot’s house, which over the years has become a historical museum, was already closed. I wanted to look for his footprints, the remains, and my legs took me towards the cemetery. The first thing I photographed was the epitaph, the inscription on his tombstone, and the book opens with that photograph. I remember walking around the tombstone, with almost a religious sensation, a bit like encircling the walls of Jericho and waiting for them to fall. At the same time, I thought about the analogy of a tombstone and a photograph, how a photograph freezes life and is also the thing that remains when life ends.

I didn’t dedicate The Blue Hour in real-time. But from today’s perspective, I can only say that I dedicate it to both my parents. By the way, my mother was very upset that in my first book I dedicated the Night “part” to her, she thought she should have gotten the Day. It reminds me of a sentence that’s very significant for me by Roland Barthes from his Mourning Diary: “If I was convinced that when I died I would meet my mother again, I would be ready to die immediately.”

One could say that both books are a kind of grief work, each one dealing in its own way with absences that are also related to the medium: Talbot—the father of photography, the specific time in which he lived, the photographic techniques with which he worked and contemplated photography. How does one decide to “walk in someone’s shoes”?

First, I took a step, without planning the whole path. The initial urge was simply to get up and travel, to reach the specific place where photography was born. There was a paradoxical dimension to this urge because it came after a relatively large exhibition of mine at the Tel Aviv Museum (Salon, 2010), which for me, wrapped up a period of engagement with portraiture. This was a period of re-examination, which was tied up with the death of the option of analog photography. I had photographed the portraits in analog, and photographing them on film had been an essential part of the whole photographic experience. At the same time it had gotten difficult to develop film, essential functions began to disappear. Today there is a return to analog photography, but in the first decade of the 2000s, it felt like a watershed moment. There were lively debates floating in the air about the death of photography, and all sorts of important figures in the field described straight photography as a dying entity, as a corpse.

That was before Instagram (in late 2010).

Yes. The feeling was of the impossibility of working as a photographer, that the world outside has nothing to offer me anymore because photography had already consumed the world in its hunger. I thought about how go on from there. I decided to travel from a feeling that my path is leading to a dead-end. In this journey I wanted to preserve the primacy, the ancientness of an unplanned encounter, a bit like a tourist with a basic level of awareness. I knew of only very few things that I did not want to do. The first was that I don’t want to try to recreate the nineteenth century. This from the recognition that one can only look at it from the distance of time, to go back in order to go forward. And I knew I didn’t want to use Talbot’s techniques. I only took a digital camera with me. When I was already in England, I stopped in London for a few days. There I realized that I wanted to shoot with the camera of the “now” a little differently, in a way that’s not entirely in sync with the contemporary. I did all sorts of experiments, and ultimately I converted my digital camera into a pinhole camera. And that’s how the project was photographed, which created the specific materiality of the images in Yesterday’s Sun, which is, as mentioned, my first journey following Talbot.

The Pencil of Nature is the first book of photography, which was printed in several hundred copies. The book, as a textual space that validates knowledge, was reborn in Talbot’s hands as a material hybrid display space that integrates photographs. The texts he wrote and published in the book contain his meditations about the future of the new medium from a personal, scientific, artistic, and philosophical perspective. How did the book itself influence your journey?

I listen to Talbot and his writing about photography and hear a polyphonic piece. His text was really written in several voices: scientist, artist, intellectual, English gentleman. But what interests me most about him is the spiritual dimension, the philosophical, the poetic. As I see it, his motivation in the study of photography is different from that of the French inventor of photography, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, who was an artist and entrepreneur. Talbot explores photography in the scientific sense and is curious about the epistemic implications of the medium for society and art. He ponders the validating aspect of photography and its fictional-literary aspect.

For him, photography and the book oscillate between their being a mechanical product—in the case of the photograph, a drawing through light without human intervention— and his being an apparatus for the human imagination [see: Vered Maimon, Singular Images, Failed Copies: Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (University Of Minnesota Press; 2015)]. And it’s absurd that of all people, Daguerre, an entrepreneur and who was interested in the general public, ultimately produces a very intimate and unique invention, the daguerreotype, from which copies cannot be made.

And Talbot, whose research was intimate, that of a thinker, produces the positive-negative method, which allowed for the replication of images and their mass distribution. His book contains the same contradiction between reproduction and singularity. It was printed by hand, one copy at a time, and very quickly fell through because Talbot and the printer he worked with could not keep up with demand. That is, the book itself was simultaneously reproduced and intimate. These tensions interest me.

When I went looking for Talbot, I was looking for his spirit (in the sense of his ghost as well). His vision shoots arrows all the way to us in the present. The first thing I knew was that the works needed to manifest in the form of a book. The manifestation entailed a desire to conduct a dialogue with nature, and to address the big bang that Talbot created. What’s called “In the beginning, he created a book.” When I worked on the exhibition of these works, I planned for the book to be a distinct individual object in the exhibition, and for the works in it not to appear in the gallery at all.

I built a model with other works for the gallery space, but very close to the opening of the exhibition, on one of those dazed night, accompanied by insomnia, I decided to throw out everything I had planned and to create instead a congruence between the book and the exhibition. So instead of the book being a catalogue of the exhibition, the exhibition emerged out from the book.

You photograph in Talbot’s footsteps the English landscape of the village and the surrounding area, trees and leaves, still life, alongside frames of his library, the famous lace, porcelain and tables. You add a lot of interior photos of the house. How did you think up this axis of nature-culture?

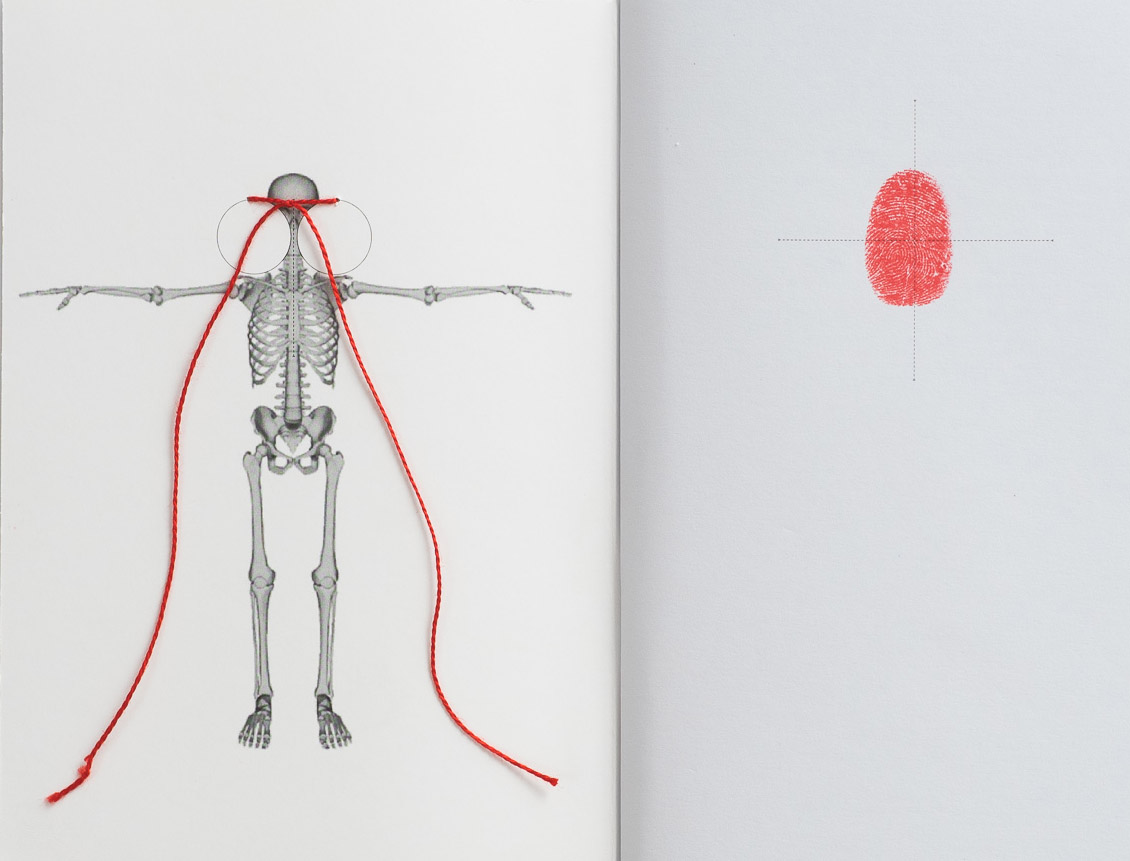

The second and third images in the book continue my movement around Talbot’s tombstone. When I reached the back of the tombstone, I observed the lichen that grew there and covered the stone. It seemed to me like an abstract painting, or alternatively like sperm stains. These are remnants of life, and this connects to the circularity in the arrangement of the book. The image of the spores reminded me of Anna Atkins who integrated cyanotype photographs of British algae into her book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843), which came out a few months before The Pencil of Nature. My spore photograph is also kind of “botanical,” a photograph of the chaotic nature, which captures on paper the moment of death of the living thing. I try to hold the rope at both ends. Although it’s impossible, I still try, knowing that it’s doomed to fail.

The image of the spores is also reminiscent of a negative that disintegrates or gets burned.

Yes, and that goes back to the first question you began with, about duality. I love that photography is inherently saturated with duality. We started with Day and Night, with Yesterday’s Sun, as opposed to The Blue Hour, and all this really goes back to the basic division between light and darkness, and of course closeness and distance. Photography demands the performative indexical dimension, “I was here,” or as Barthes put it, it “flows like milk towards its signified.”

But even though photography seeks to be inside things, to be in physical touch, what is taken from it is precisely touch, because it needs the distance. From point zero there is no image because observation requires perspective. This pendulum reflects my inner need, which photography illustrates. The camera is a gateway between me and my subject. I travel to meet my father, by moving away from him. I have to leave my homeland, my father’s home, to meet him in a kind of bypass surgery, in a meeting with Talbot. I search to reach the point of blindness.

Speaking of blindness and materiality, you mentioned in our preliminary conversation that a strange thing happened with the cover, which made it seem stained. Does it connect to the chaotic aspect of the organic quality you talked about? What actually happened?

The covers of the two books are made from the same material with different tonal versions, a paper that gives the sensation of plastic and organic skin at the same time. There’s no image on the two covers, only the blind embossed title. I wanted people to approach the book a bit like the blind, with no insight as to what was inside it. That the initial encounter not involve conceptualization, but rather touch and sensuality. They warned me at the printing house about the type of paper I used in the book, which caused the cover to get a kind of “skin disease” retroactively.

This only happened with Yesterday’s Sun. When they wrapped the copies in the shrink wrap machine that wraps each copy of the book in plastic, it created moisture that became trapped inside the plastic. They didn’t really know how to explain to me why this happened. It didn’t happen to the second book, which I printed in Germany. It created a kind of stain on the black cover, similar to the lichen on the tombstone. A kind of metonymy for this negation, which I talk about in both books.

About the connection between the chaos of the spores, the stains, and the sperm, in Yesterday’s Sun, you weave together photos of a character named Mr. Kronnagl who is sort of your alter ego, a phantom of Talbot, and an object of passion. You take portraits of him, echoing your earlier homoerotic photos in Day Night. Among other things, you photograph him in the moment of coming on a spacious bed. How does erotic, sexual gratification relate to the process of mourning?

An hour ago, the photographer Boaz Aharonovitch was at my studio, expressing his passion for one of the semen works I exhibited at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. And we had a discussion about just that: about the duality of semen. The climax is also the fall. Growth and collapse, vitality and negation, it’s not possible to separate them.

Can you elaborate about your semen pieces?

During an artist residency in Düsseldorf, I took a package of 120 blue cyanotypes with me that I had prepared in advance in Israel, which are created when the emulsion is exposed to the sun. I took these virginal papers and fertilized them on German soil. Only two of 120 papers, were exhibited at the Israel Museum. On the one hand, these works look like the essence of vitality, Jackson Pollack style, the guy who ejaculates, full of virility; and on the other, there’s the actual moment, when the substrate absorbs the liquid, a moment of collapse.

In this context, there’s a quote from Kafka that I love about books, about how books have to wound and stab us and affect us like deep grief. Books need to affect us like a disaster, like the death of someone we loved more than we love ourselves, such that “the book must be the ax that will pierce the frozen sea within us.”

It reminds me of works with an indexical dimension by your father, Moshe Gershuni. For example, his margarine works from the '70s and works from recent years, in which it’s obvious that he really painted with his fingers. Is there a dialogue with your father here, in this context as well?

Absolutely, yes. Already during my bachelor’s degree at Bezalel, I took my father’s handprint and worked with it as raw material. I had in mind then the texts he put into his paintings. For example the text, “I am here,” is an interpretation of the indexical action in a painting, one that imprints itself one-for-one. This declaration about presence also had a dual dimension for me, an existence that declares itself out of a great absence.

In this context, Hagai Canaan very nicely links the indexical aspect of Talbot’s light drawings to the melancholic structure of the psyche according to Freud. In The Blue Hour he writes, “The object casts the shadow of its absence on light-sensitive paper, thus creating a negative, or shadow.” What was the genesis of The Blue Hour?

It was a bit like the placenta of the first delivery, the important placenta that came out of the same uterus, two years later. They’re like siblings, carrying the same genetic baggage and the same shared childhood memories, but their DNA is mixed in a different way. The book consists of photographs I took using Google cameras, translated into a digital negative, and printed as blue cyanotype prints. They were positioned in the book as diptychs, and the exhibition was also built in pairs.

But in the book, the photographs appear in black and white, and not in the cyanotype blue and white that appeared in the exhibition. Why?

I’m trying to recreate what the motives were. I think I had different wants from the existence of these images in the book. I wanted two types of encounters, first of all for myself. I wanted to have the images in it not as singular like a cyanotype, but as a glorified mass and also to tell a story.

This book is edited linearly; it has a kind of beginning, middle and end. Precisely because the book is matter and the original images are digital, I felt the need to make their physicality within the book redundant, “to bring them back to their roots,” in a way that continues the task of the first book. It reminds me of Talbot’s sentence, where he describes images that appear on the glass at the back of the camera obscura; he calls them fairy pictures, “destined to fade away.”

In The Blue Hour, there are actually images that “disappear” due to digital disruptions to the transmission of visual information over the web; there is something undermining about them. You said you were trying to create a story. What story? How did you edit?

I wanted the mass to create a pretty boring story. No hysteria or drama, no catharsis. You start and slowly you are caught in the dead-end of boredom. I built a script for myself, which doesn’t appear anywhere, but is related to parents and children. In my head the children were abducted from the village, the parents became orphans, and then the children returned to the village. This is the story that guided me as I edited. It’s a hidden story, like a latent image. I don’t offer it up like a key, but it’s there. I wanted to entrap the viewer in a story of continual discomfort.

Interesting. So one could say that the first book deals with a fascination with photography’s past, and the second deals with boredom with the current state of photography, or with the state of affairs of “everything is photographed and permission is given”?

They both swing back and forth. I think of these books as a midpoint between wakefulness and dreaming, between reality and fantasy. For me photography is always like that, it requires you to meet with the world, only to turn your back on it.

Who did you work with on both books?

I worked with Gila Kaplan, who is also a very good friend and a super talented designer. We made the first book while she was still here in Israel before she moved to Berlin, and we printed it here too. We made and printed the second book in Germany.

We worked on everything together. For example, there were all sorts of ideas for fonts, and in the end, we found a font that was created in the nineteenth century. We bought it especially for the book. It felt right, that the creation of the font would be close to the birth of photography, a kind of index for that time. Nirit Binyamini, who worked with Gila at the time, designed the logo of Yesterday’s Sun in a particular way, which did not rely on existing fonts, a bit like The Pencil of Nature’s cover has graphic elements that wrap around its name.

And the perfect paper?

We went to the printing house together to go through papers, to talk about how they feel. We were looking for a paper that, on the one hand, would create a sense of the “antique” and the “historical,” something that has withstood time, and on the other hand also very much belongs to the present. In addition, in several places in the book, we used thin Bible paper. It is also a kind of humorous wink to Talbot because this type of paper was used to protect photographs and illustrations in nineteenth-century books. I don’t have any precious photographs, my book was not printed manually, everything is offset printed. But I try to give the photographs a gem grade quality with this paper. To make the cheap expensive, the “basic” rare.

Similarly, I used the term "Plates" in the titles of the photographs, just like Talbot. But I don’t have any plates or negatives in the material sense, there isn’t even an original print. It’s a game of opposites. In the same vein, Yesterday’s Sun has a straight spine, which is a convention of the present, and The Blue Hour has a rounded spine, which is a convention from previous centuries.

So to sum up, making this book was like…

The obvious analogy is the experience of birth, and there is a lot of truth in that. It’s something that carries your genetic components, edited and bound DNA. But in the context of our conversation today, I think it really is a kind of grief work. Because it’s prolonged, intensive work, it makes it possible to deal with the loss over a period of time, rather than being overwhelmed by melancholy. It has an active dimension. It’s a bit like looking into the printing press, into the gears of time.

What book should we add next to our library?

Eran Naveh and his wonderful book God Almighty published by Golem Publishing.

Where can readers buy the books?

Contact my gallery - Info@chelouchegallery.com

"I went to “meet” Talbot at a very critical stage in my relationship with my father, when I was conscious of the time that was running out. He was very ill then. And that awareness, of finiteness, led me to embark on this journey as a kind of preparation for parting. I went to meet in order to say goodbye."

"There I realized that I wanted to shoot with the camera of the “now” a little differently, in a way that’s not entirely in sync with the contemporary. I did all sorts of experiments, and ultimately I converted my digital camera into a pinhole camera. And that’s how the project was photographed, which created the specific materiality of the images in Yesterday’s Sun".

"Precisely because the book is matter and the original images are digital, I felt the need to make their physicality within the book redundant, “to bring them back to their roots,” in a way that continues the task of the first book. It reminds me of Talbot’s sentence, where he describes images that appear on the glass at the back of the camera obscura; he calls them fairy pictures, “destined to fade away.”

"I wanted the mass to create a pretty boring story. You start and slowly you are caught in the dead-end of boredom. I built a script for myself, which doesn’t appear anywhere, but is related to parents and children."