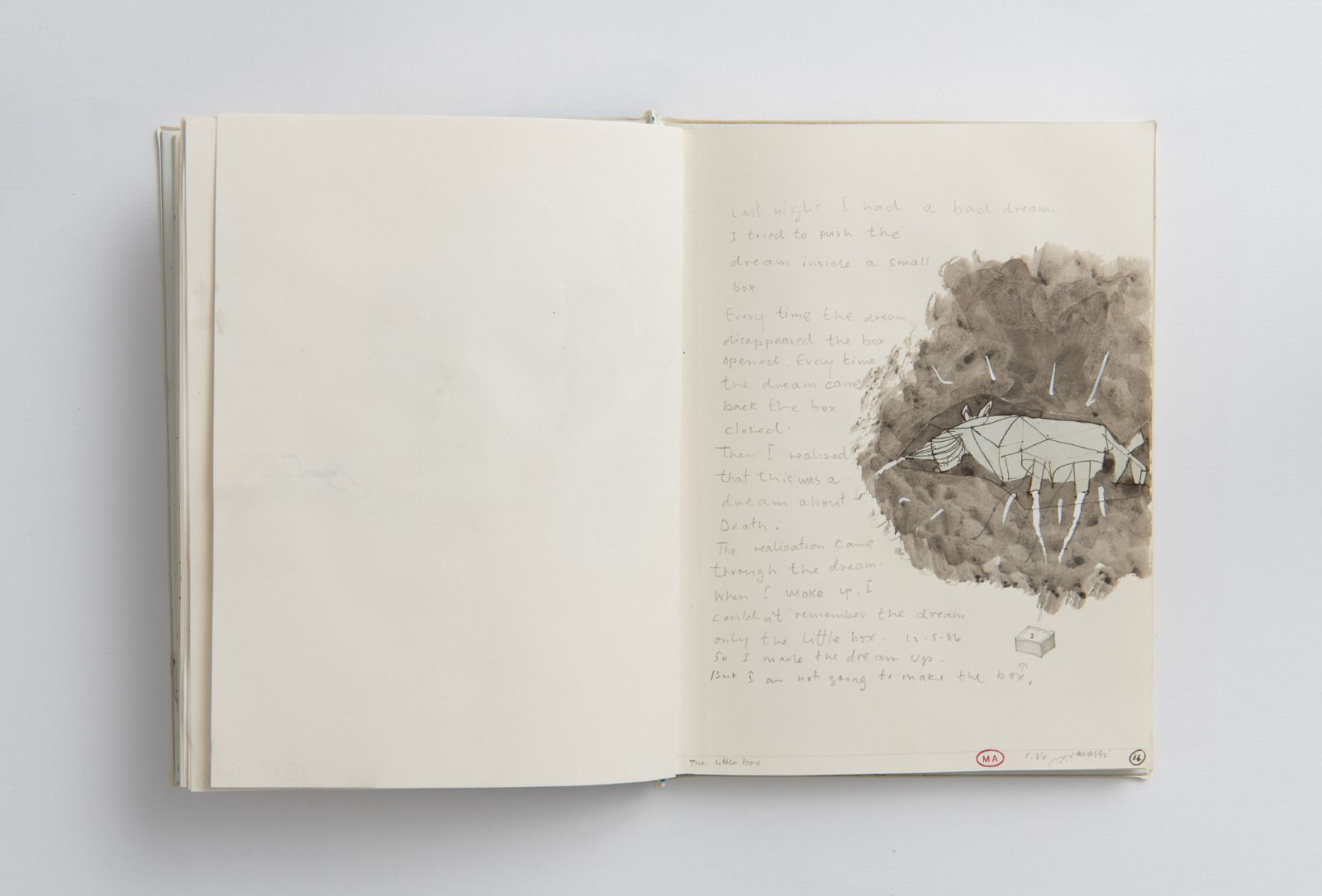

The Little Box

“Last night I had a bad dream. I tried to push the dream inside a small box. Every time the dream disappeared the box opened. Every time the dream came back the box closed. Then I realized that this was a dream about Death. The realization came through the dream. When I woke up, I couldn't remember the dream, only the little box. So I made the dream up. But I am not going to make the box.” [12.5.86]

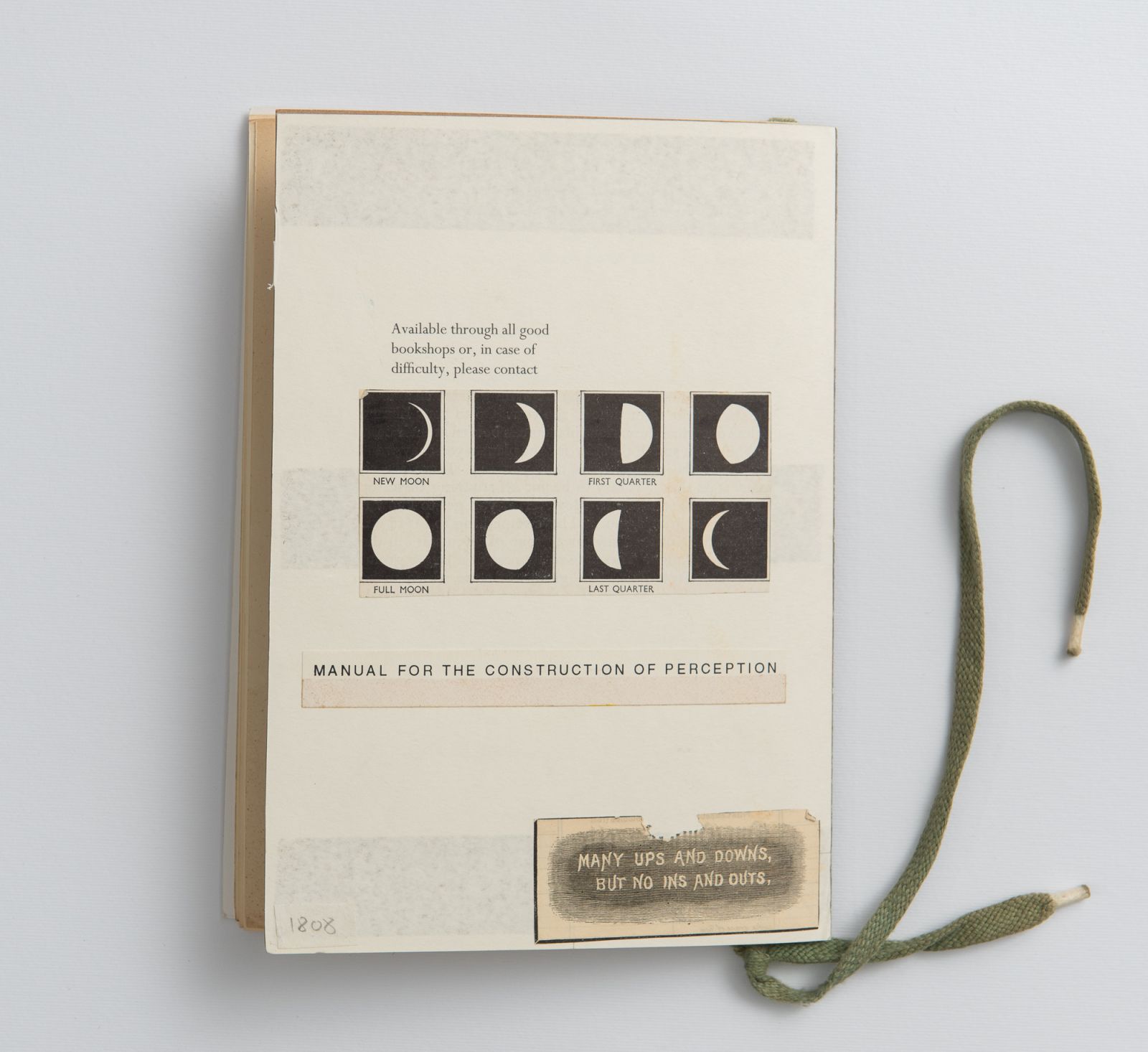

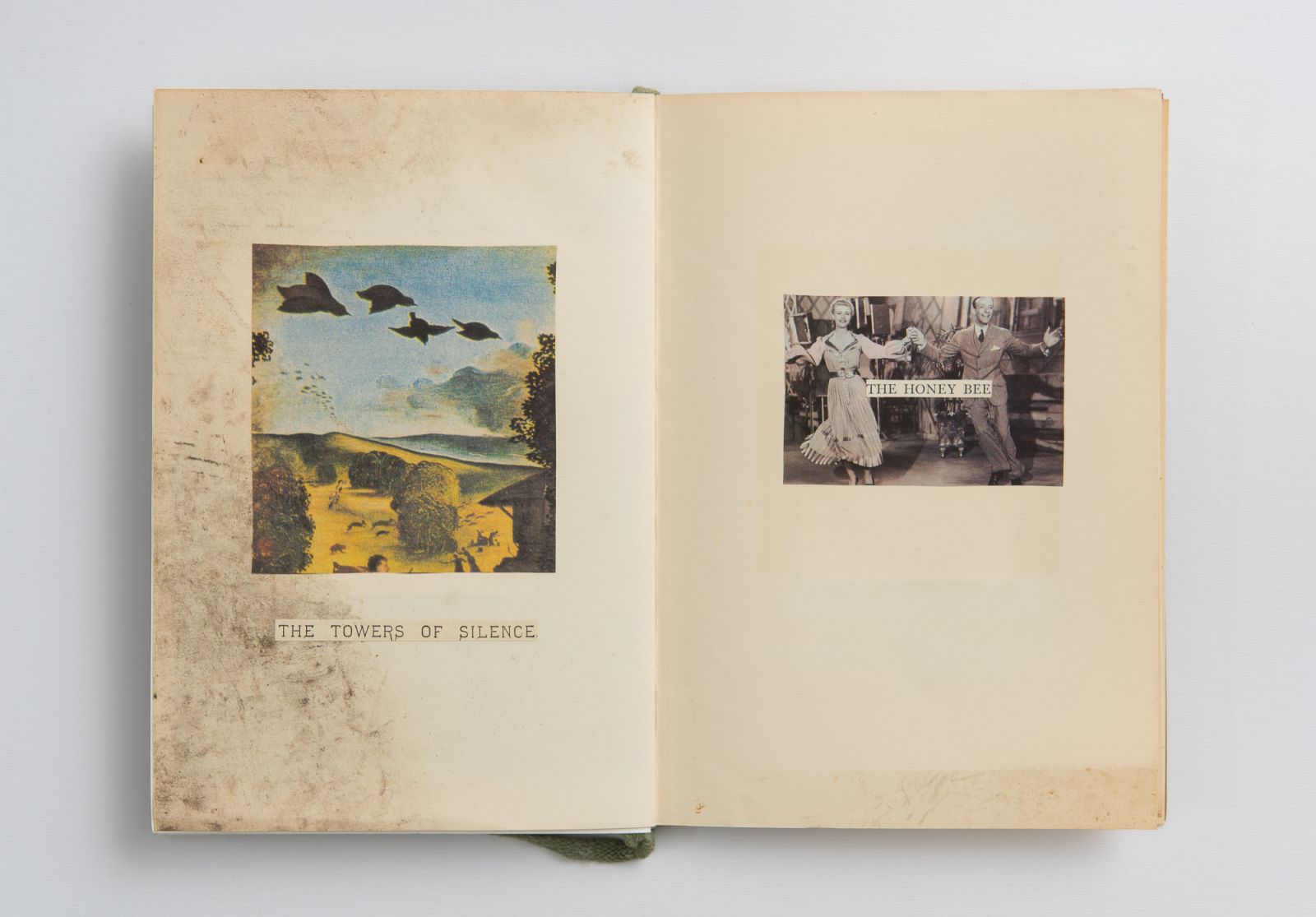

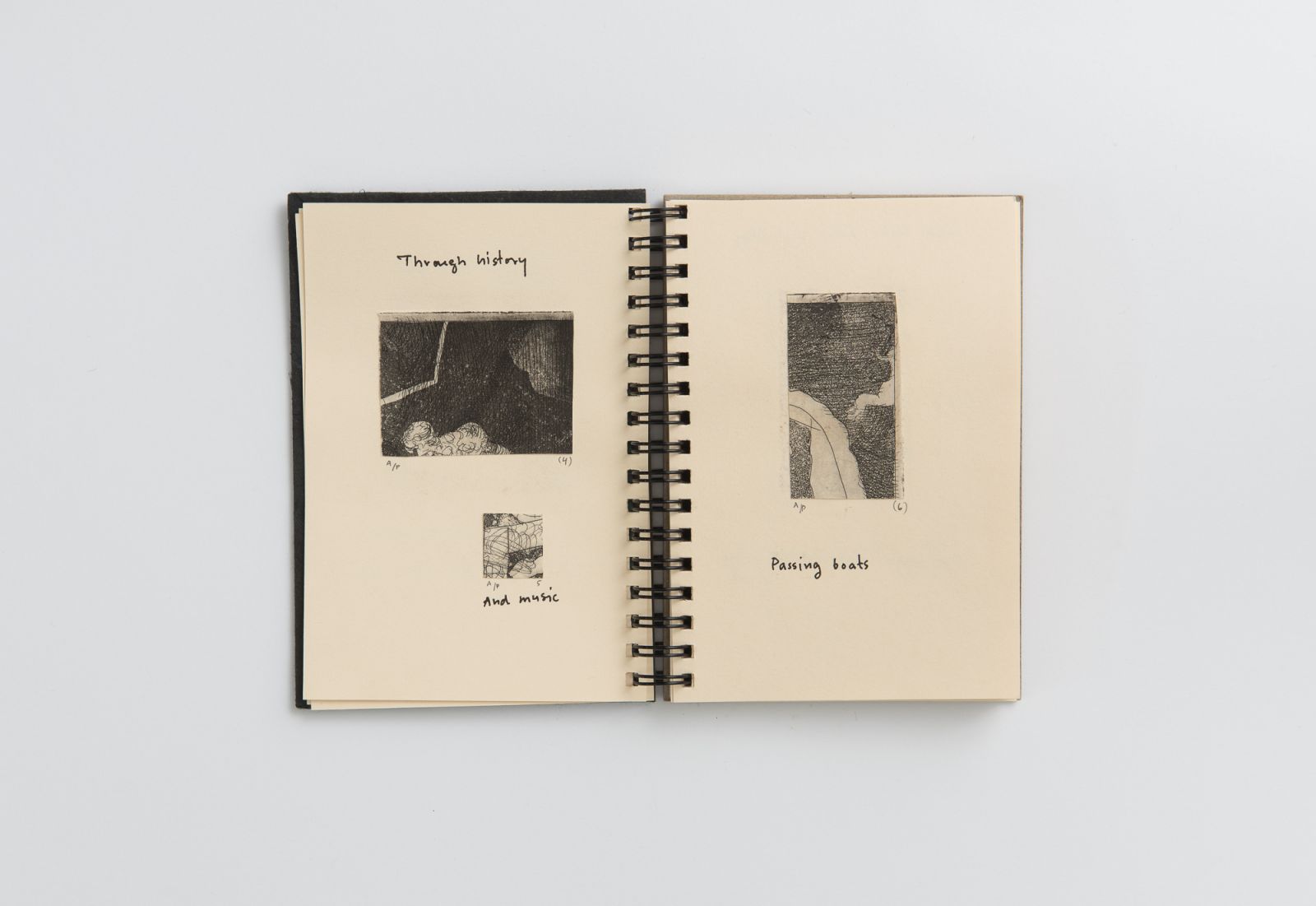

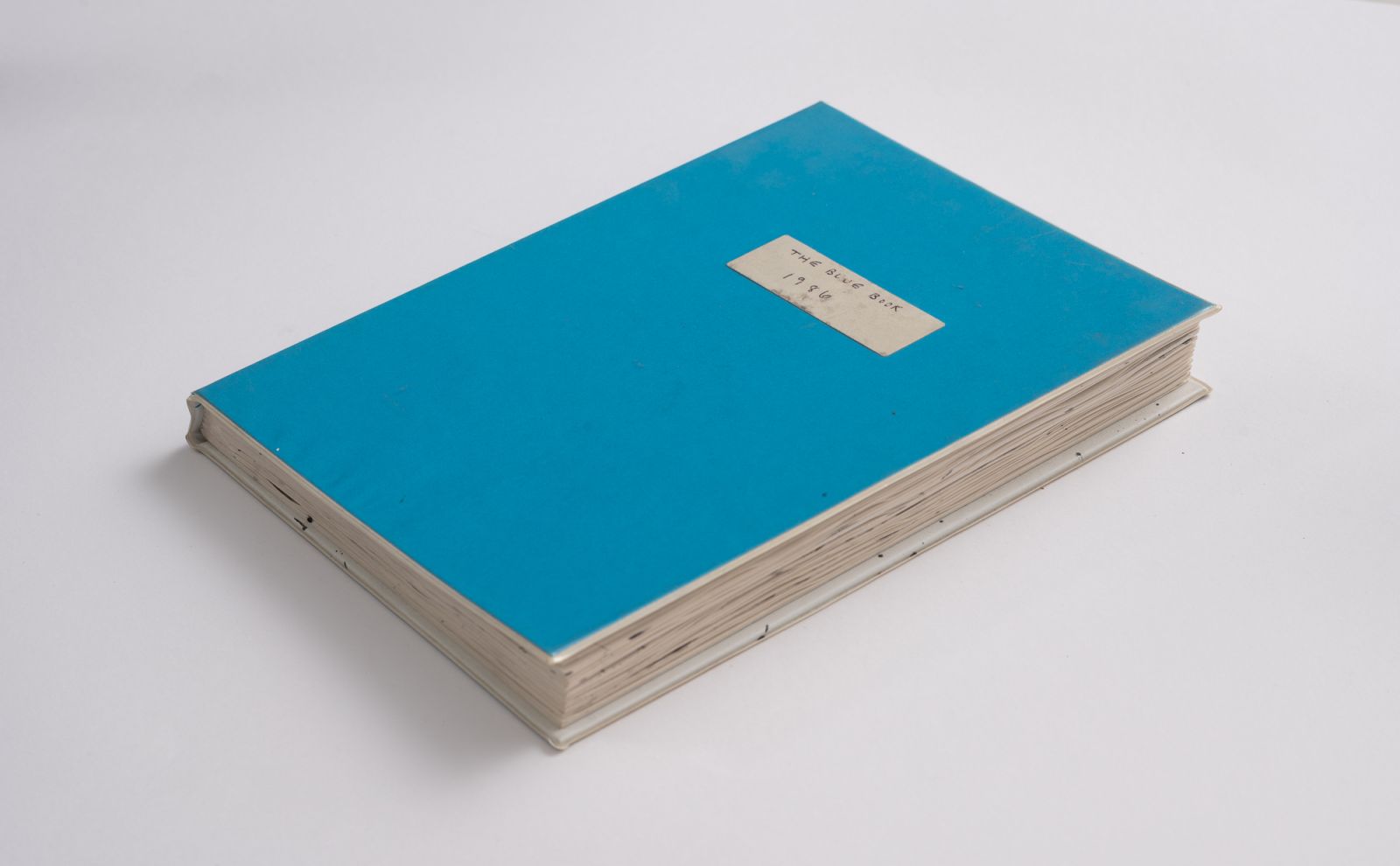

From The Blue Book, an artist’s book by Meir Agassi [1986].

Avshalom Suliman: We have waited quite a long time for this conversation, as if we had been saving up something that was precious to us both and kept putting it off until the right moment. I am here thanks to your and Yaniv Shapira’s invitation to look together at the artist’s books created by Meir Agassi, and especially because I missed out on Meir in real time. I think of him as the one who influenced my own entry into the world of culture and art, on my very ambition to become an artist. Long before I understood what it means to live in art, I built a model for myself around the story of his inner struggles, a model of a creator that I, as a young person, could identify with. For me, Meir was someone to mourn even though I never knew him personally. You are here as an artist and an archivist. You have photographed dozens of Agassi’s artist’s books in the Mishkan Museum archive, meaning that the impulses of “archiving” and “numbering” are significant in your work.

Shiraz Grinbaum: Incidentally, regarding initiation stories, my first meeting with Meir Agassi is related to the very first time I saw an artist’s book. Yair Barak sent me to the Ein Harod Mishkan Museum to look for the book The Lines of My Hand by Robert Frank. I sat at the table that had belonged to Agassi, and I said to myself: Wow, this is everything you need to be an artist! I felt that everything I needed to know was right here, in this library. This moment remained submerged in my consciousness for many years until it resurfaced as a huge passion for artist’s books. I remember going shelf by shelf, through the Marxism and postmodernism, theory, poetry, and art; through all these neatly organized shelves.

You describe a very beautiful moment of insight.

That day I shot five frames in the library with 35mm film and they came out very dark. In retrospect I realized that I shot the library as a sort of black hole, a place to be swallowed up in.

In the last three years, you have been very busy with archives – you built the archive of the Activestills Collective, the website for the late Joav BarEl, you helped establish the website for the late Micha Kirshner, and more. The Ma’alelet website you founded has now become a cumulative archiving project for artist’s books published in Israel, which just went live on the internet under the name MADAF: Artists’ Books. Are you more consumed with the present or the past?

Ma’alelet was a joint process together with Yair Meyuhas, inside the labyrinth of local artist’s books, which gave birth to an archive with an all-consuming motivation. You mentioned the archive of the late Joav BarEl. I think that Joav’s generation and specifically his peers – Yona Wallach, David Avidan, Yair Hurvitz and others – were very sensitive to currents and potentials that received less space in local art. From today’s perspective, Joav’s resolve, like Agassi’s in the generation that followed him, was about the multidisciplinary, about not being one thing. Today it seems obvious to us, but they were among the first to point out this possibility as something that was achievable.

This generation is now passing on before our eyes.

Yes. I feel that in this generation of the 1970s, which Agassi was greatly influenced by, there was a lot of potential that was lost after the Yom Kippur War. I’m thinking of Fluxus playfulness, the preoccupation with Zen and the East, pop as a political potential, psychedelics on the edge of spirituality. Even the conceptual movement which was really pulsating, got a kick in the face from the war. It’s as if after ’73, everyone... everyone went back to being soldiers.

Wow.

You don’t think so? Wounded soldiers, but soldiers. Is that why we have such a fascination with this generation?

The fascination is that we try to understand our parents.

Yes. When I read Agassi’s materials in preparation for our conversation, I experienced this rupture, the threshold of orphanhood. ... Now there is no one to ask. There is the library.

Regarding Meir’s library – the real one, the metaphorical one – what do you think he built with it?

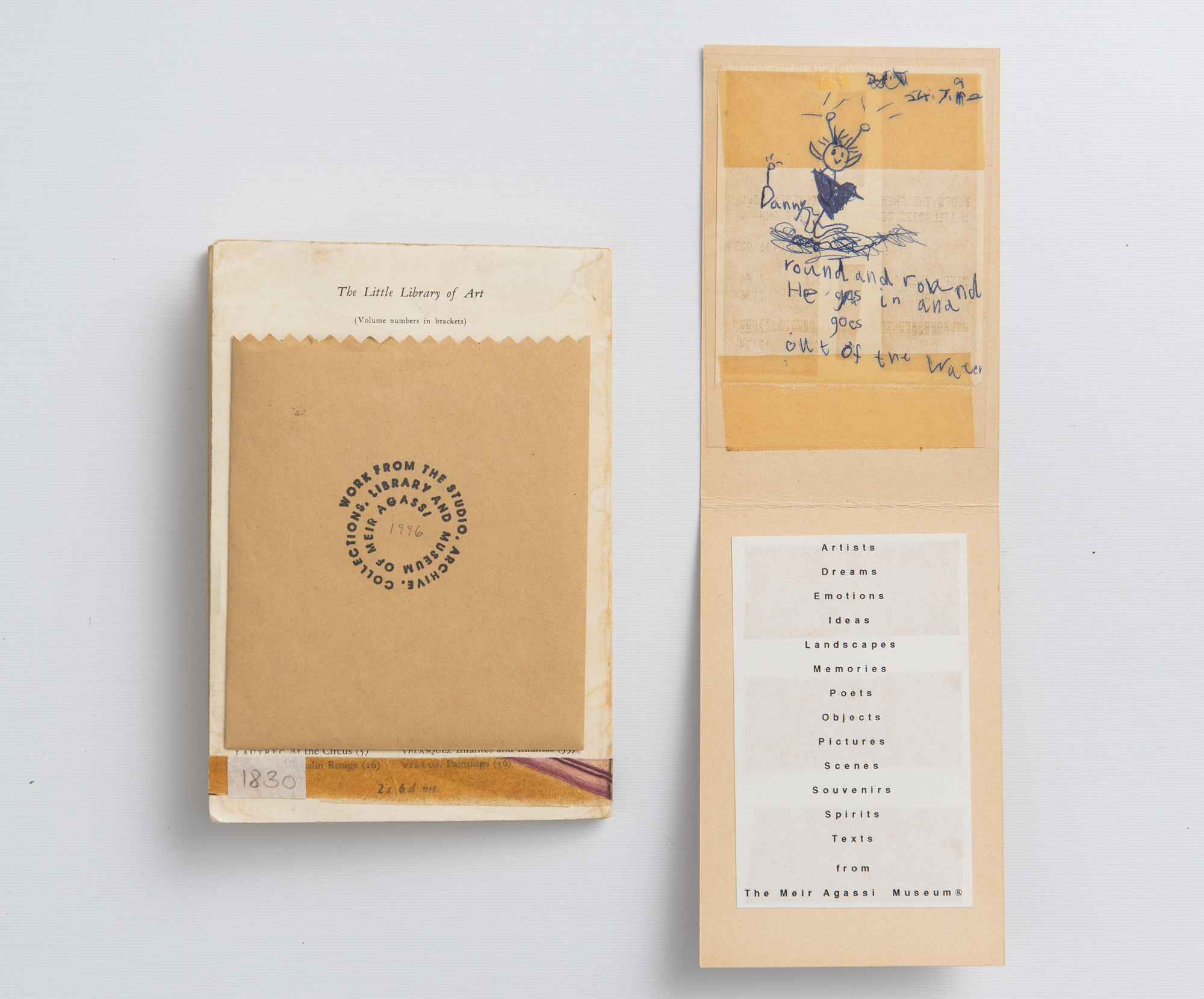

Agassi is the occupant of his own archive, he is the “dweller” and we are the custodians. Naomi Aviv writes about it very beautifully, about its sense of urgency, to do all the time, to produce. About images that are born out of each other. The characters and his work and the library are so intertwined that it is impossible to separate them.

Courtesy of the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod.

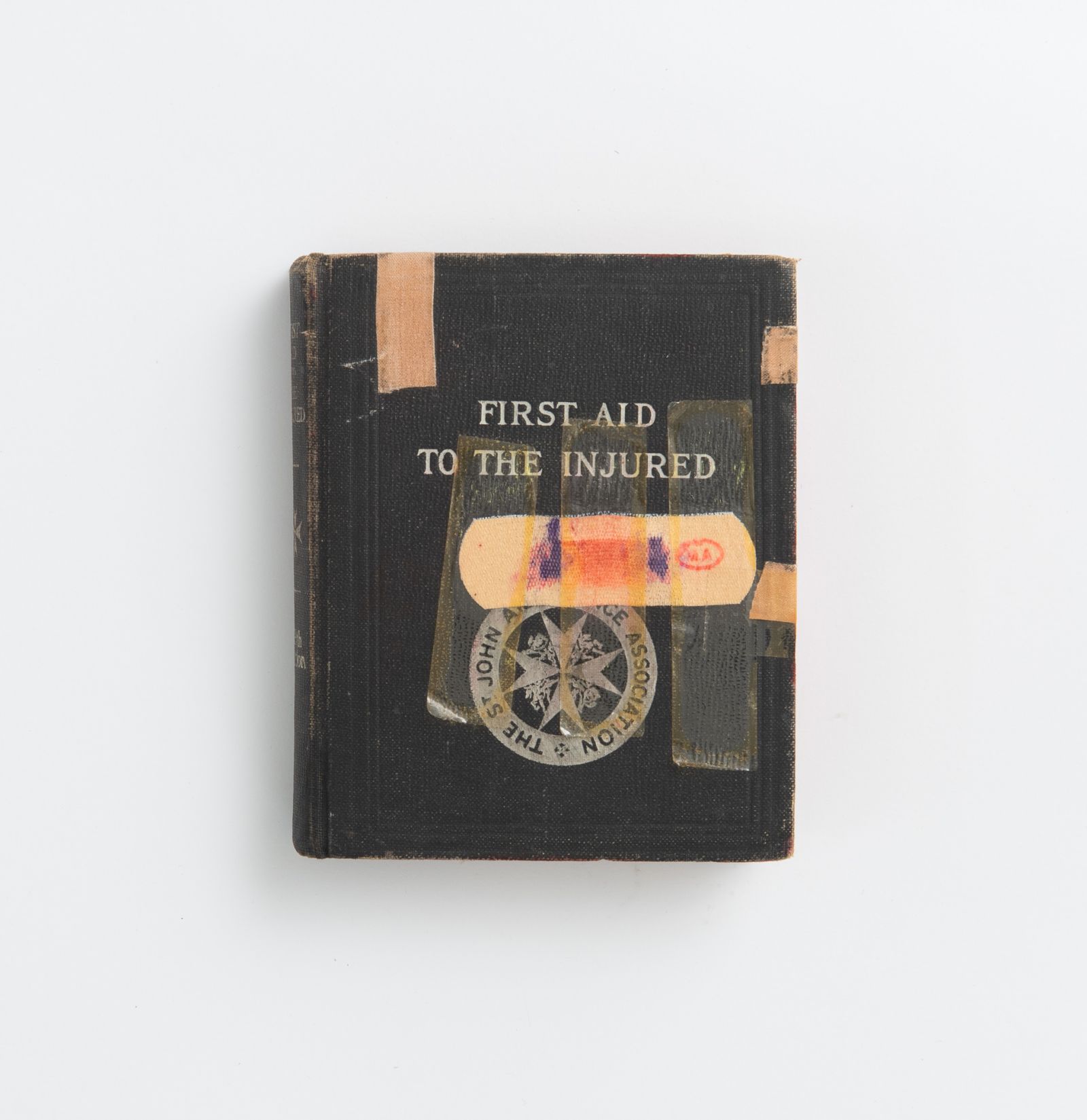

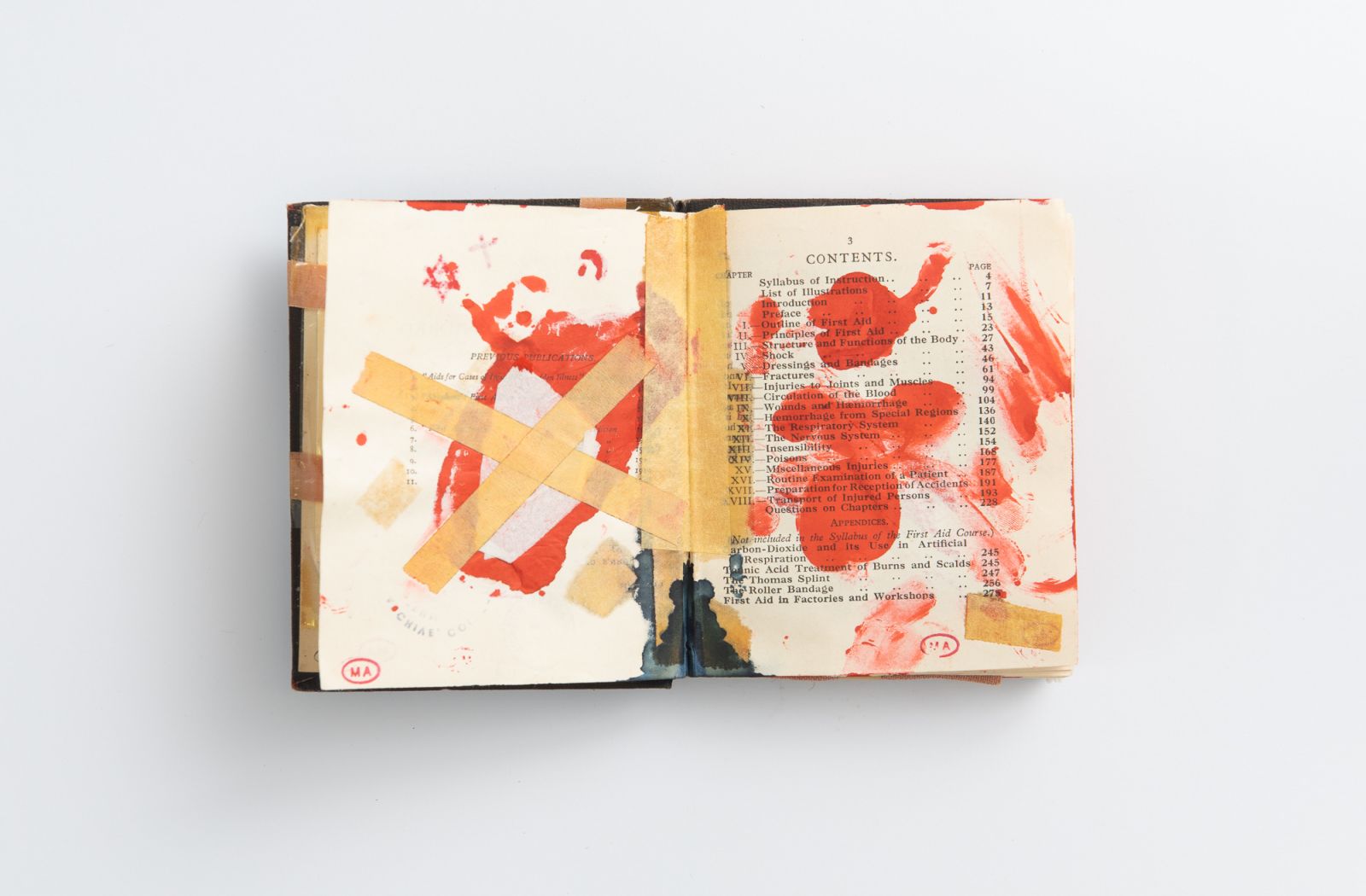

First Aid

So let’s agree that up to this point we have stood in front of the door of the archive, of the museum. Let’s talk a bit about the experience you had when you documented Meir’s artist’s books. Look, these are objects with enormous power, versatile, personal, and at the same time show the full breadth of the canvas that Meir dealt with, as if they were meant to be stages from which he transmitted signals to the “outside," to beyond the Meir-Agassi universe. They are also like incubators for the different types of thought that Meir has been performing for years: sketches, ideas for sculptures, experiments with materials. You see how he tries the different voices; that at some point will become the artists he created for himself, who will embody and speak the many voices within him. Maybe you can choose one and tell what you took from this experience?

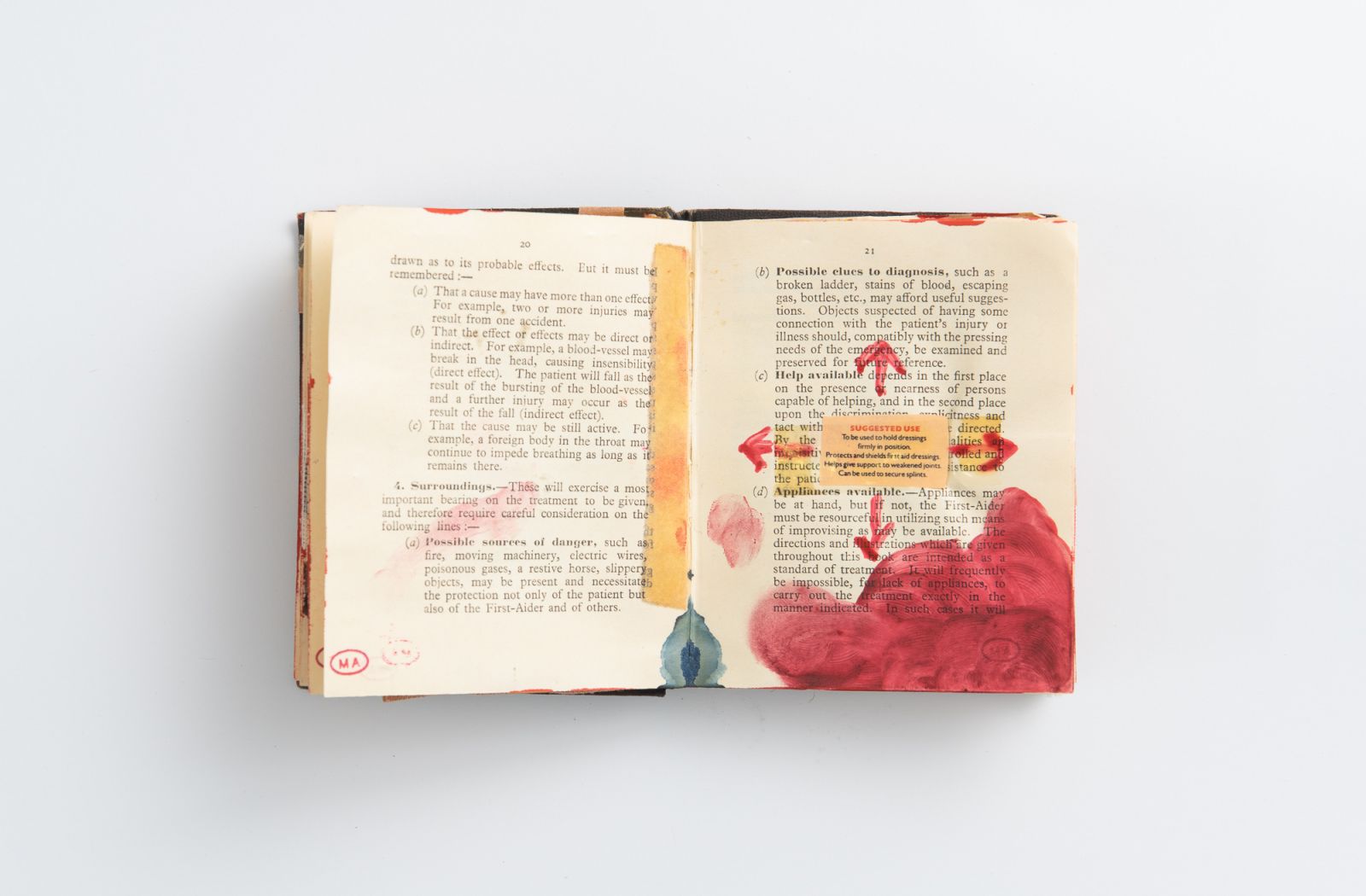

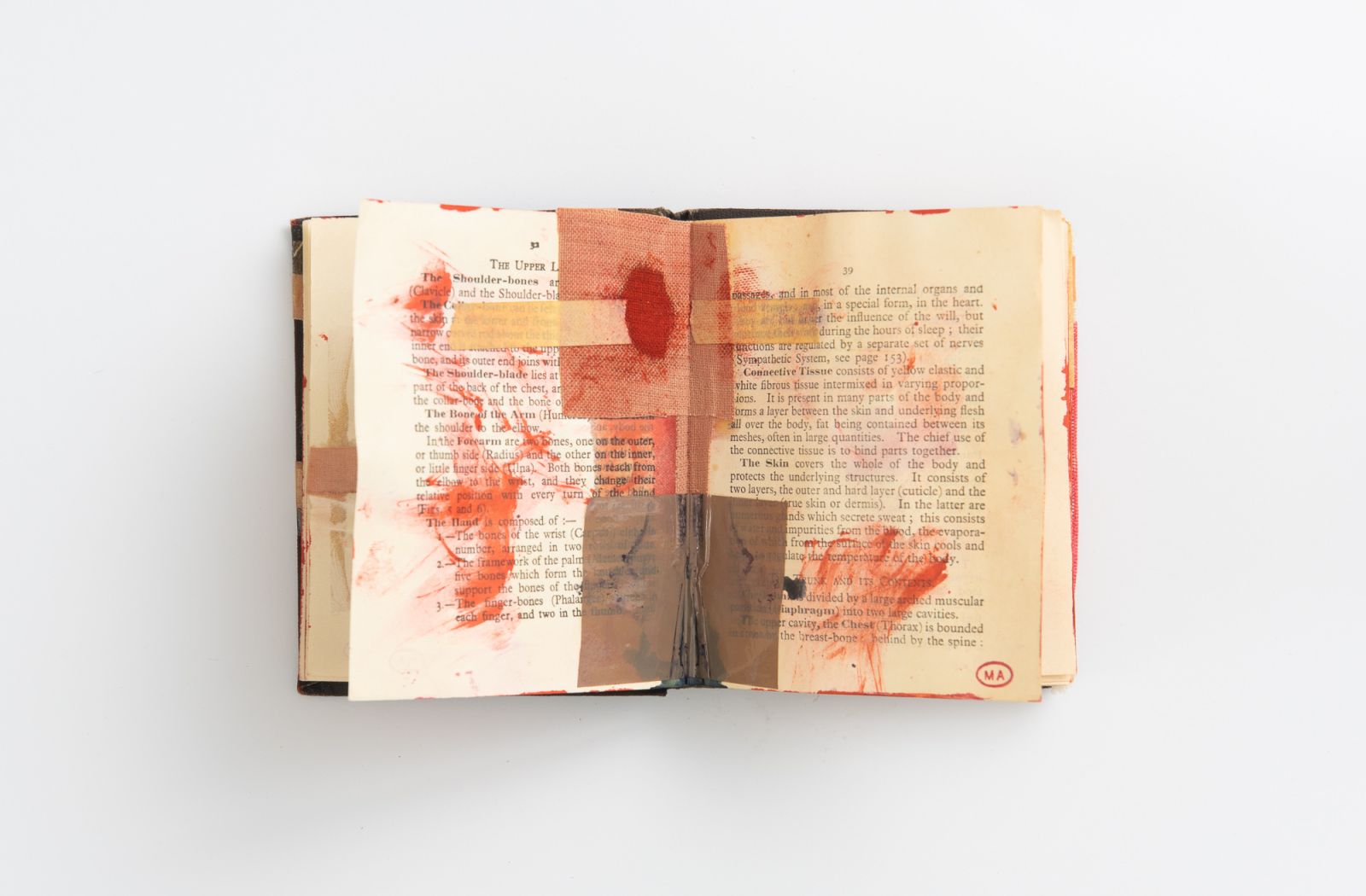

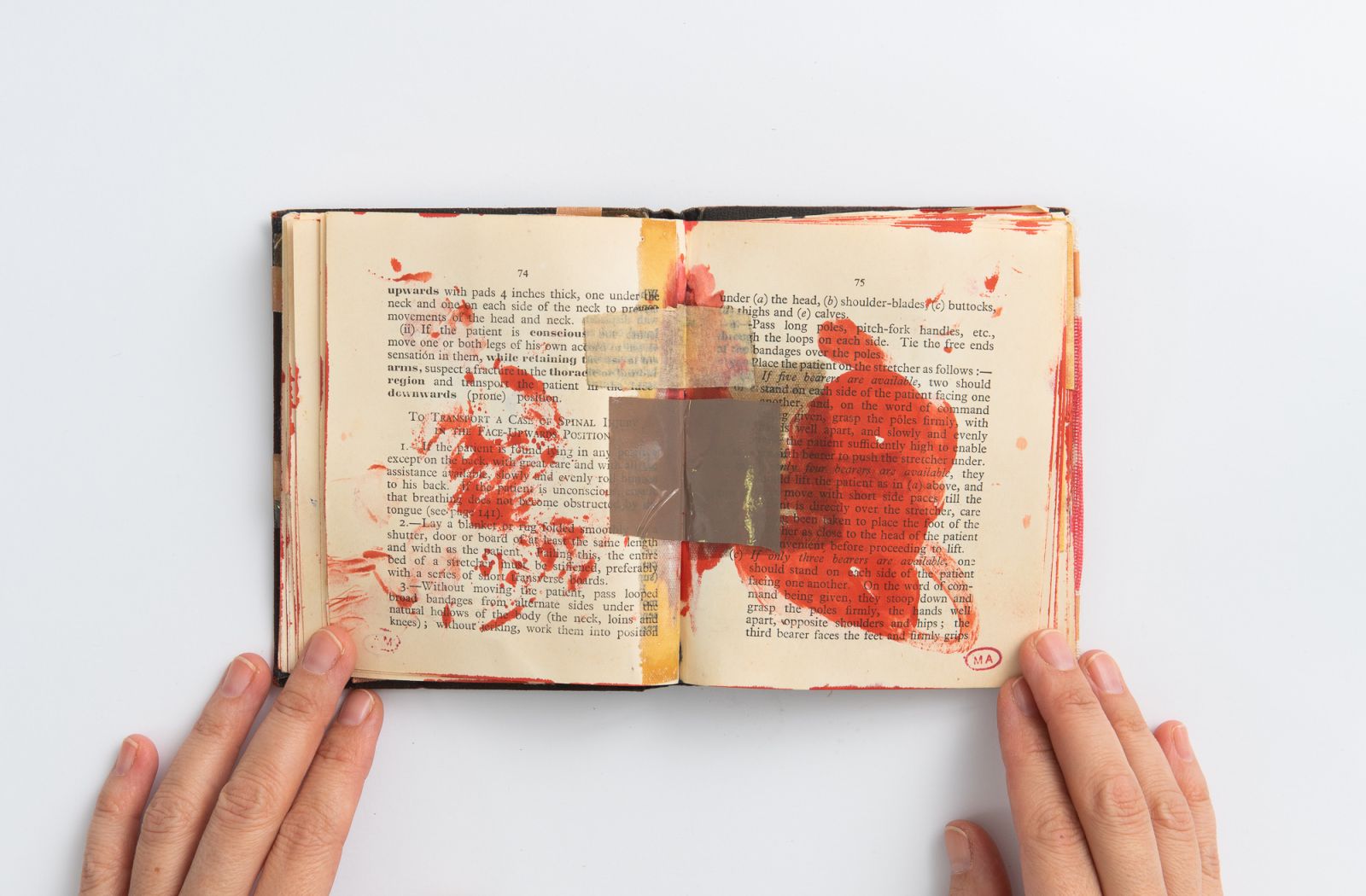

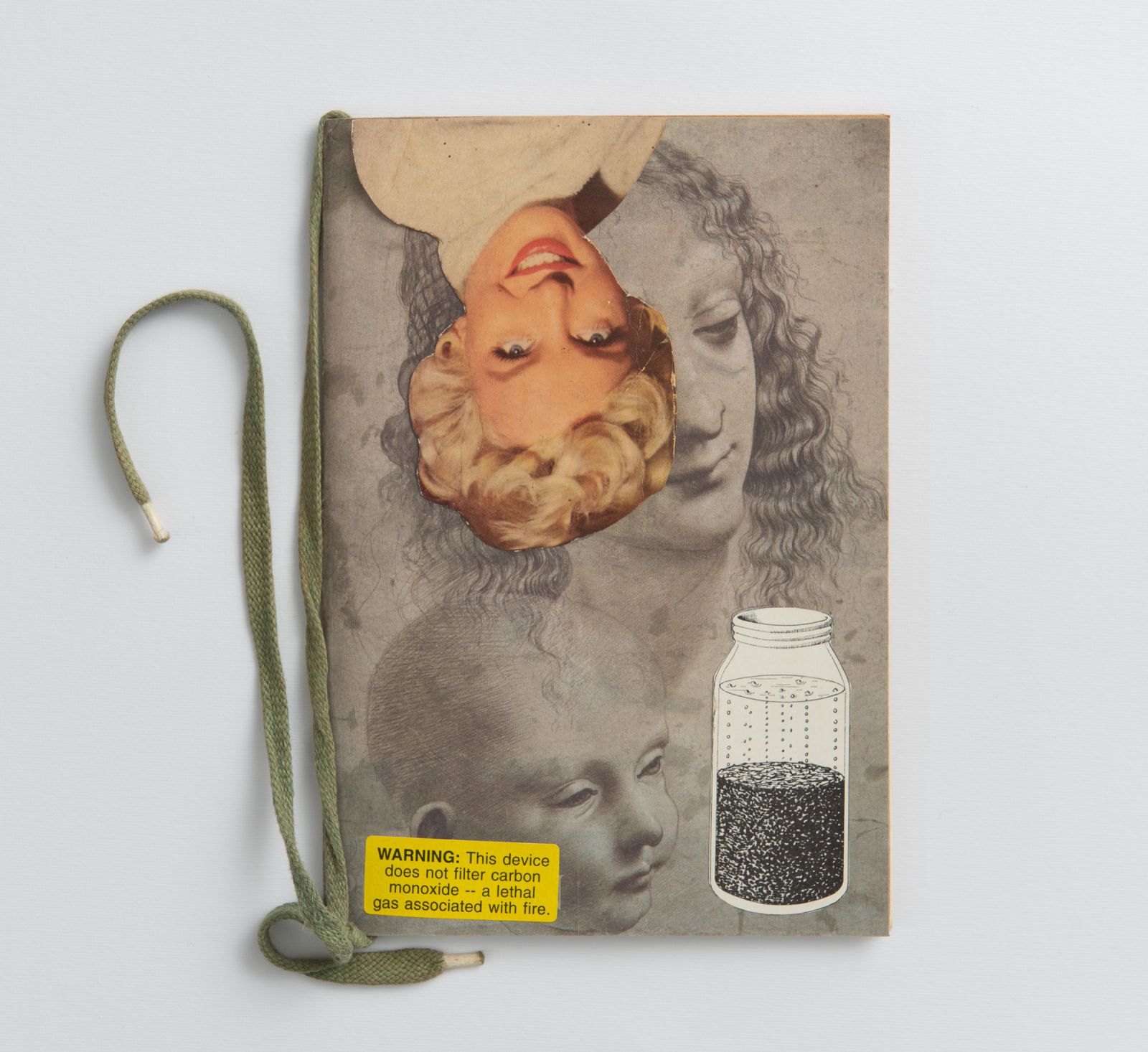

The first thing I chose is the book First Aid, an object that looks like a small black notebook. From the font, it’s probably some British pamphlet on how to dress wounds, and Meir just covered the whole book in adhesive bandages and painted it blood-red. Genius! Since I’m always looking for the trauma, this is the first book that spoke to me – it’s genius how it creates such a sense of horror, that the more the book is bandaged, the more wounded it actually is.

This reminds me of another work, a miniature silver notebook that I held when Yaniv Shapira hosted me in the archive, called The Collected Poems of Sylvester Stallone. Inside there are only two transparent pages, with an adhesive bandage attached to each of them. Also First Aid is actually one work, isn’t it? Meir’s touches are watercolor and red ink markings, bandaging made of masking tape and pieces of fabric, and of course the “Meir Agassi Museum” stamp that appears on almost every page. It’s actually the same action, one action.

In his archive of artist’s books, there are ready-mades that he works with; printed booklets like this one. There are the Bezalel notebooks, kind of bound sketchbooks that were sold in a store in Bezalel – at least twenty of them, all in a grid of the months of the year, which gives them a diary-like sense, a kind of daily self-examination, perhaps. And there are a lot of books that Agassi constructs, and these are very graphic and sculptural objects: concertinas, or book covers that he turns into kinds of three-dimensional objects, or a small book the size of a miniature book of Psalms that is actually an object with a flower on top. A book that is a flower. A one-time thing that blooms and withers.

Soft cover, four pages, 5.5X5.5 cm.

And brochures, gift boxes, packaging, and booklets inside boxes the size of a matchbox, and postcards, and various containers that hold limited edition works. He created in this whole range long before the idea of the museum was born in 1992, so actually when you look at all these objects you are looking at a bubbling, a proliferation of ideas and images. I see this multiplicity of voices as a form of internal struggle to find one’s voice, and the birth of the museum as a surrendering to compromise, a renunciation of a single self. The museum is the formalization of the multiplicity, of the non-one, and what enables this multiplicity to live. And it is perhaps also a conceptual and formal framework that allowed him to deal with his persona as a journalist and writer who was appreciated, and as an artist who rarely exhibited, whose projects perhaps – and this necessitates historical investigation – were difficult to come to terms with.

Your claim is very interesting because for me, it suddenly connects something about this generation. I think about trauma, about the wound that started to open in the generation of the ’70s. The trauma that splits the self and produces the multitude of voices. It suddenly clarifies for me something about their need to not be one thing. It’s also interesting that in those years and in the ’80s a lot of artists left here. Today, in a kind of ironic inversion, if you’re not “interdisciplinary” then you’re not with it. But are we really interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary as artists, today, in the sense that they were?

Maybe in this sense Meir’s project and also those of others you mentioned here, is a project that was not exhausted.

They have tremendous commitment, to follow the idea to the end. Like the book First Aid. You can’t do one page. You can’t mark it. In retrospect, all of Meir’s work deals with marking – because he is constantly asking “What is the source?” But then, in the end there are no shortcuts. He checks everything, all the options. Every book has some theme and he works with it. This matter of the concept, you have to carry it through from A to Z. How can I put it…

You need to implement conceptual art in the body?

You need the modesty of the doer.

Because?

Because you have to explore the idea until it finds itself, otherwise there is no point. It is classicist, yes. But there is a lot of modesty in taking one idea and making a hundred versions of it. Agassi is an example and a master of how an idea should be carried out from A to Z, until the last page in the notebook.

This is a major statement. It’s very important. You’re talking about modesty, as opposed to the opportunism of a single shtick.

The taking it to the end seems to me to be a significant key to the story. In an inverted logic, it’s also a bit military, isn’t it? To run until you can’t anymore. But it’s discipline, it doesn’t have to be military.

You brought a xerox of the outline of the museum that Meir apparently created in 1992. The powerful thing about this sketch is that it gives equal weight to personal, mental processes, artistic actions, and different artistic personas. In other words – it is a self-portrait, and it’s really moving if you read it in depth. For example, the word “Art” is not the only desired goal. It is related to Poetry and Literature and leads to four professional titles – Painter, Sculptor, Installation Artist, and Printmaker – to each of which Agassi added a question mark, as if to say “Printer?” “Painter?” and so on. Or for example, in his outline “obsessions” leads to “collecting,” “archiving,” and “creating catalogs,” but logically, also to “making collages” and “publishing.” It’s an idiosyncratic and private logic, wouldn’t you say? But it shows a map of being-in-the-world, of how to live life, not of planning career moves.

That’s right. Yesterday, I scribbled here, “Knowledge not as a mechanism of power but as the discovery and embodiment of a private world.” This is the way that opens up from within. It’s interesting that he didn’t exhibit much in his lifetime. It’s very private, “Art is a private thing.” Who said that... Adam Baruch?

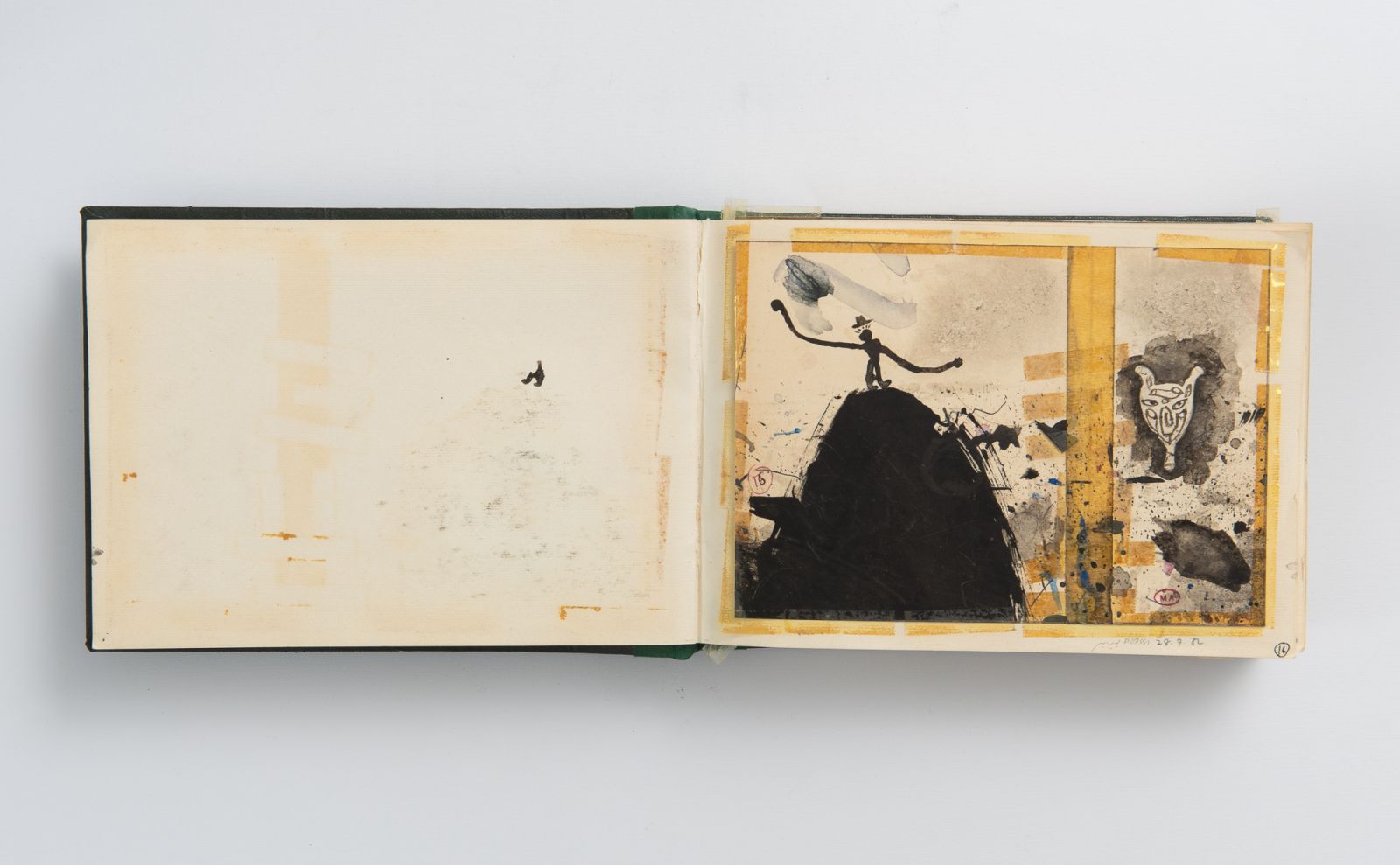

A collage of watercolors, ballpoint pen, pieces of poetry, papers, and photographs.

I think he really wanted to exhibit. And alongside that there is the image of the librarian, the archivist, the scholar, the one who sits in a room and creates the world, similar to what a writer does, and Meir is, for me, the most sensitive and smartest of the artists who write about art in the Hebrew language. And this makes me appreciate his project as a total life project. Also the reticence – in terms of the medium and conceptually. When you look at the scope of his work, what stands out is the fact that his production techniques were very chamber-like, manual. This connects to the image of the immigrant artist who works with what there is around him, whether he is “at home” in Tel Aviv or in a small apartment in Bristol. He organizes a physical and mental space for himself that is equipped with everything he needs to create, just like you felt years ago when you sat in his archive. Migration is the same migration – inward – and from it he can do far-reaching actions with very few means.

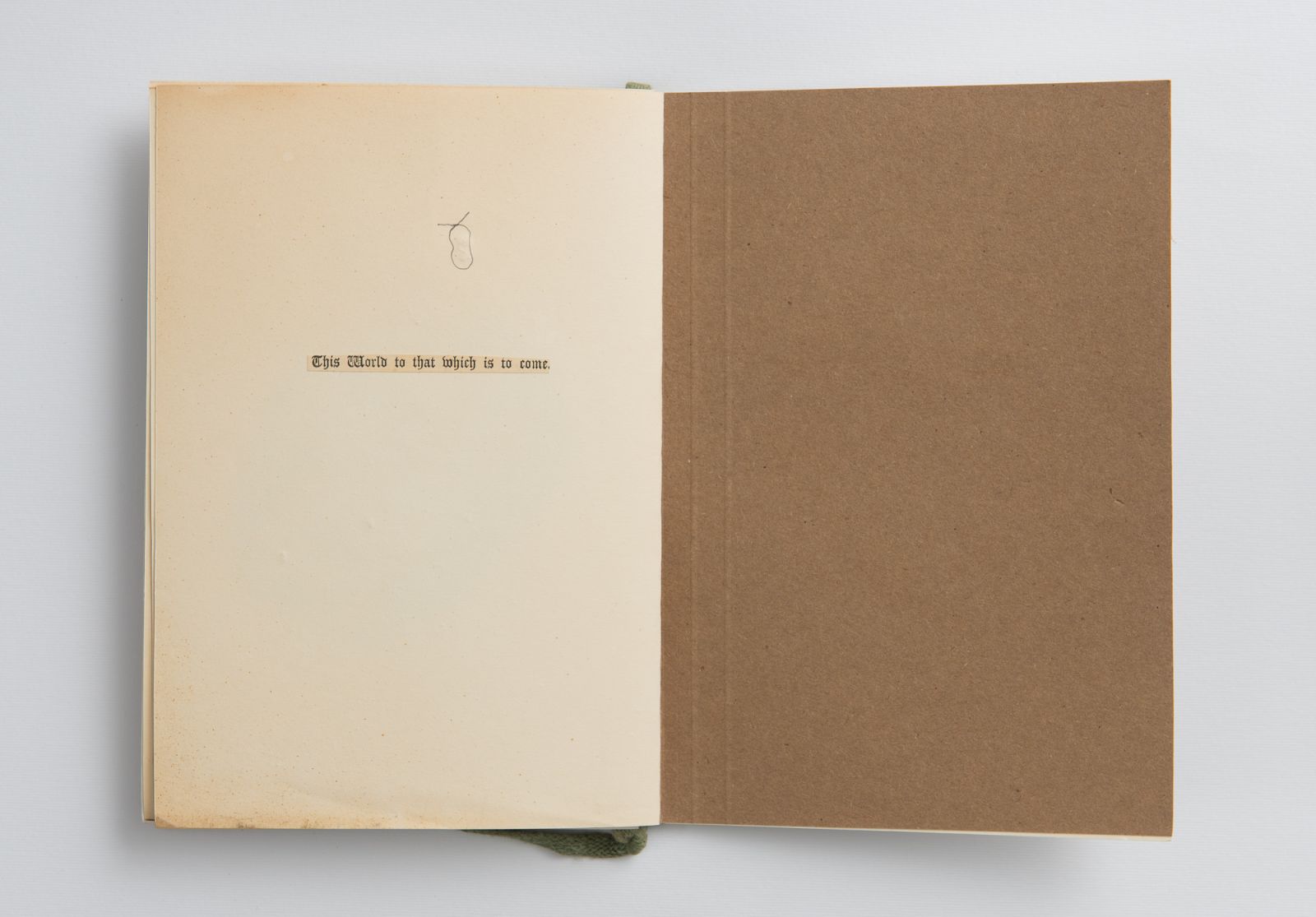

Here, for example, is a collage from another book, called The Pilgrim’s Progress (1996). It is a double spread whose main image is a tourist postcard of a tropical island with the title “Dream Destinations” in large, yellow, all capital letters. Agassi filled the background using watercolors in free strokes of green and blue that seem to continue the turquoise of the water on the postcard. There are two Victorian oval portraits of young women and a self-portrait of Egon Schiele, in the background of which Meir attached a print of a Gothic-arched space and below the word “wrong,” identifying the image as a painting by Cézanne. Will you read the quote pasted here?

Collage: ready-made photographs, drawings and text.

“The story of Pablo Picasso and the women in his life as seen through the eyes of Francois Gilot, his mistress, mother of his children Claude and Paloma, and the only woman who finally found the strength to leave him.” There is something in this book that draws on Max Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness). Mainly the atmosphere of the dream, the compositions whose logic is not the deceiving of the viewer (one painting with the title of another) but the fluctuating logic of the dream, or fantasy.

At the end of this book is a final message... “This world to that which is to come.”

It is a sign of a journey.

Yes, he always has some kind of mental projection towards the future. Faith perhaps.

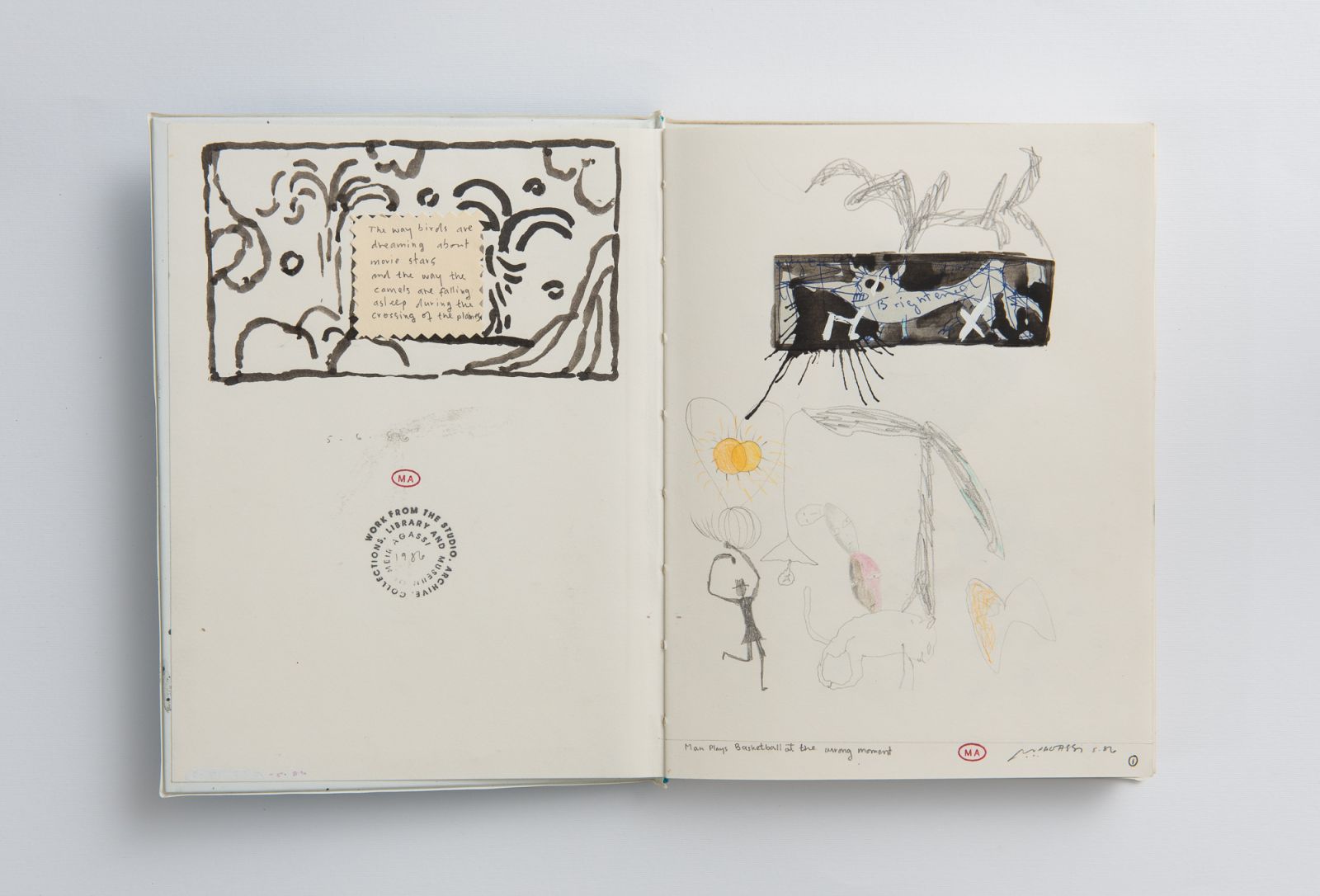

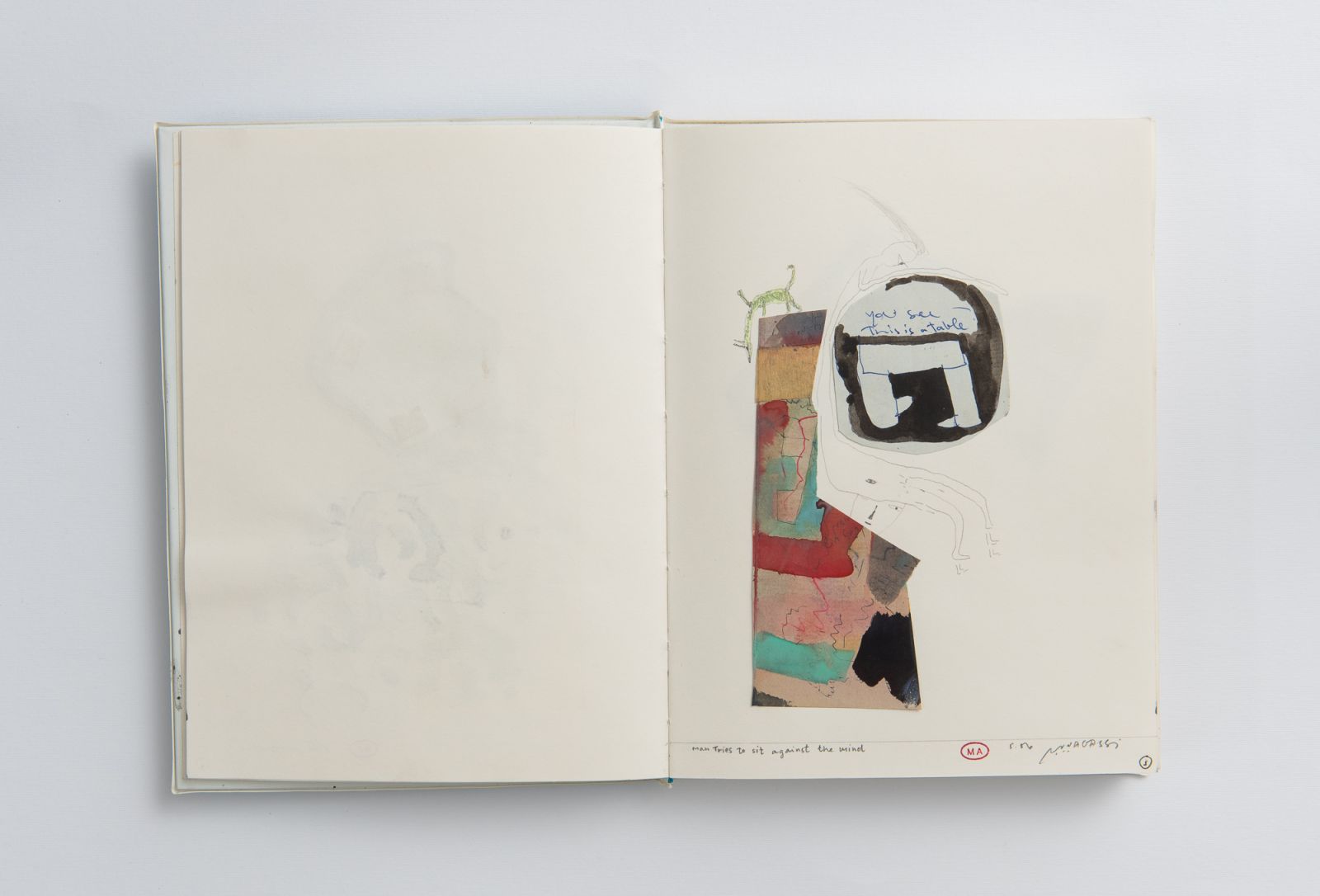

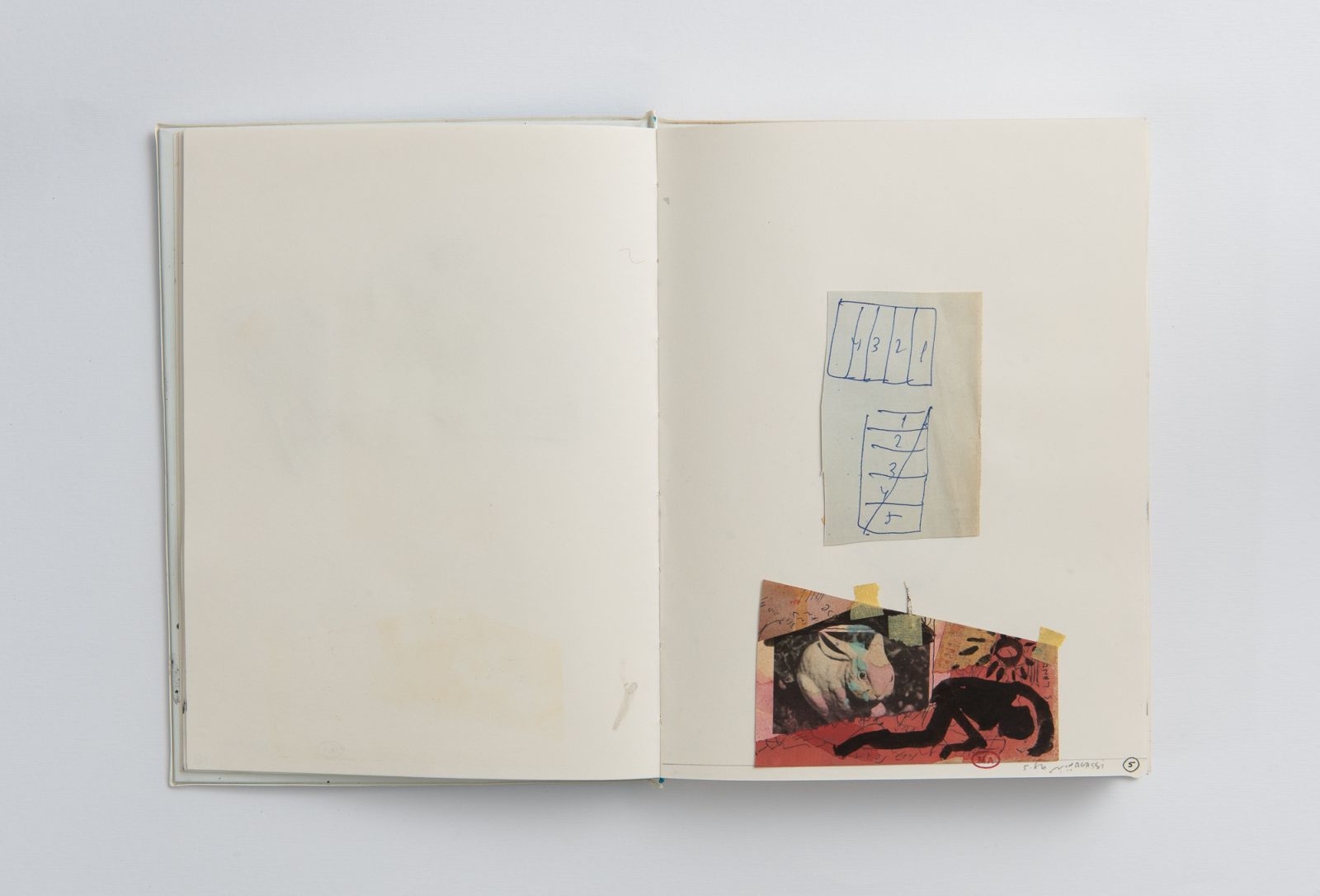

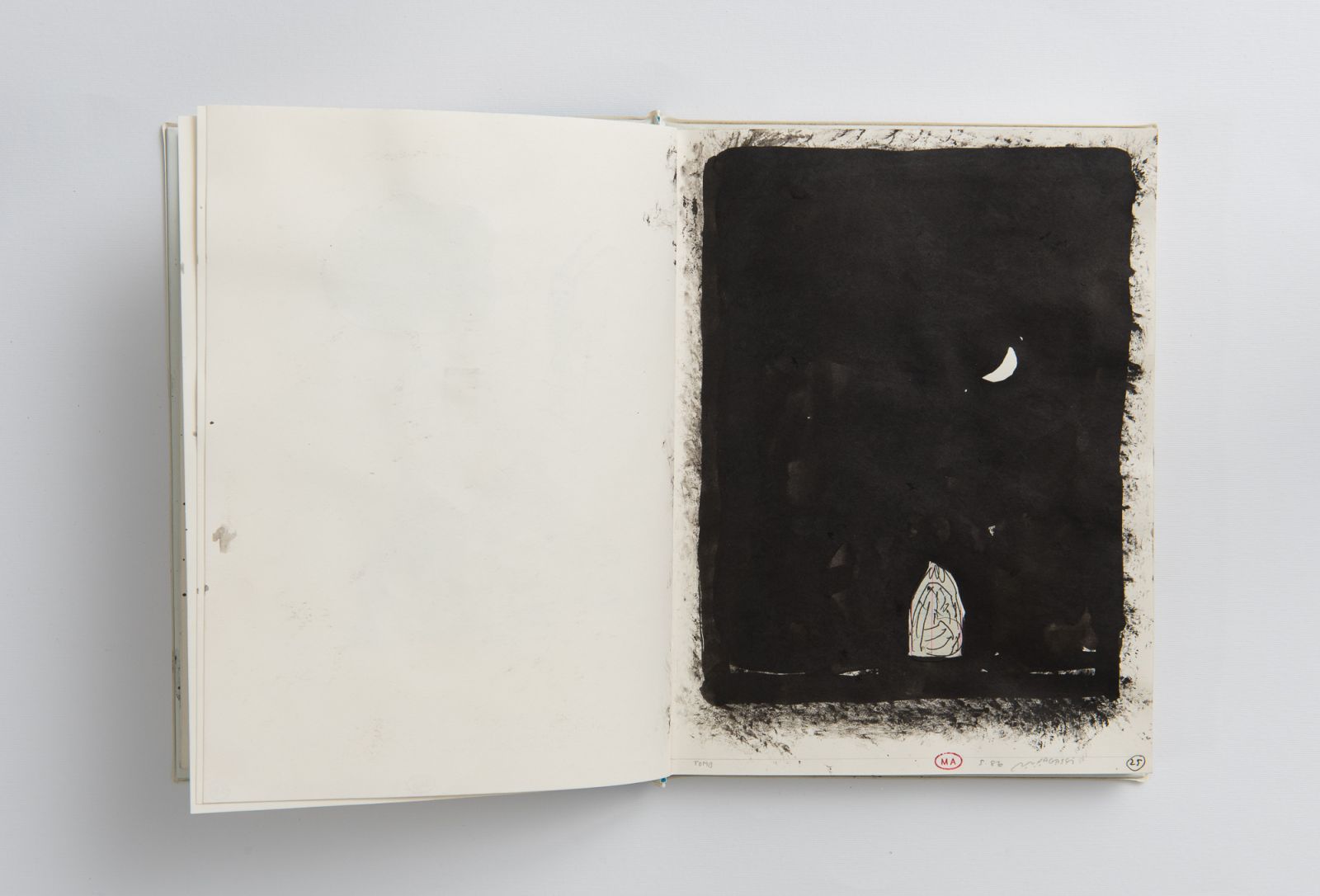

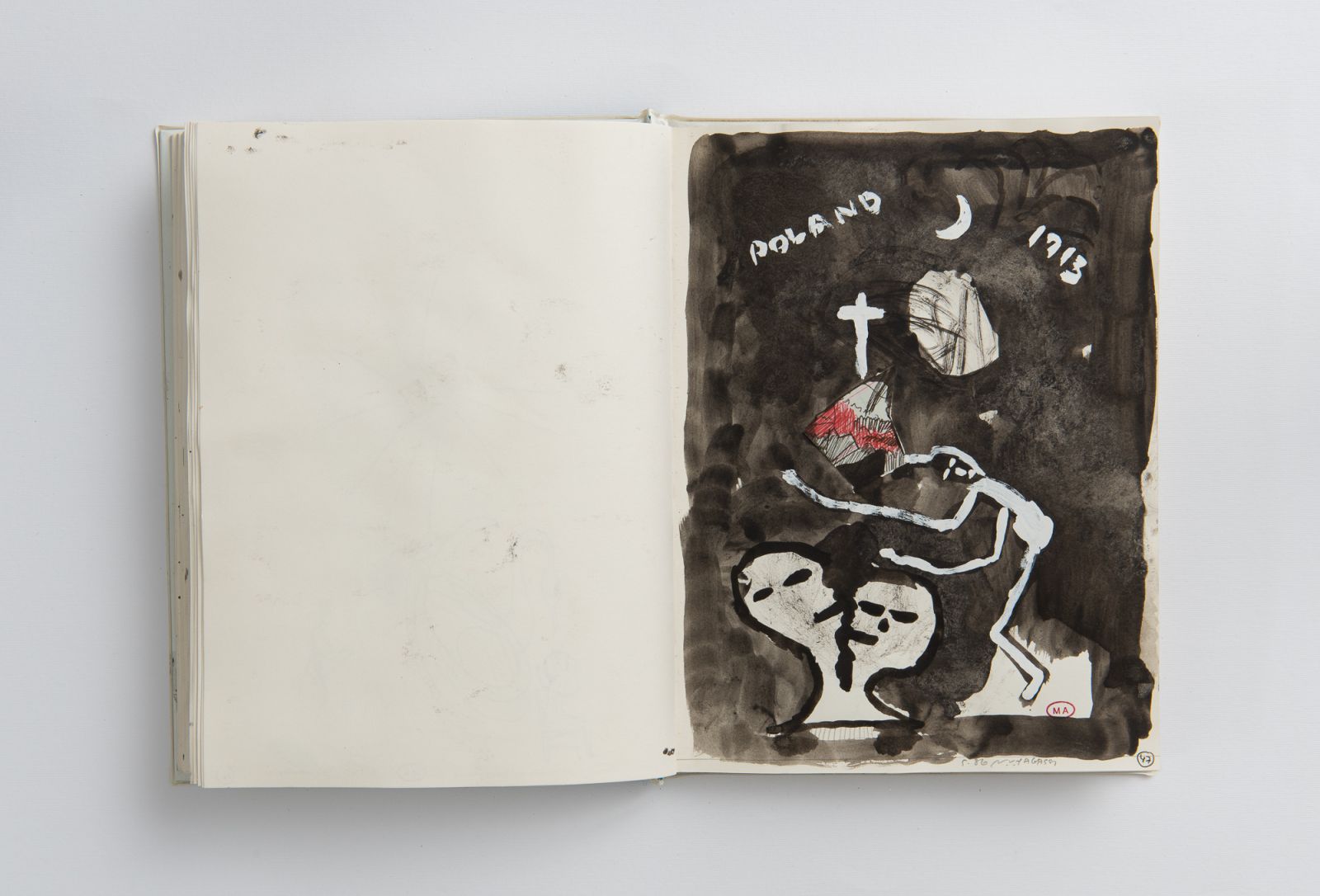

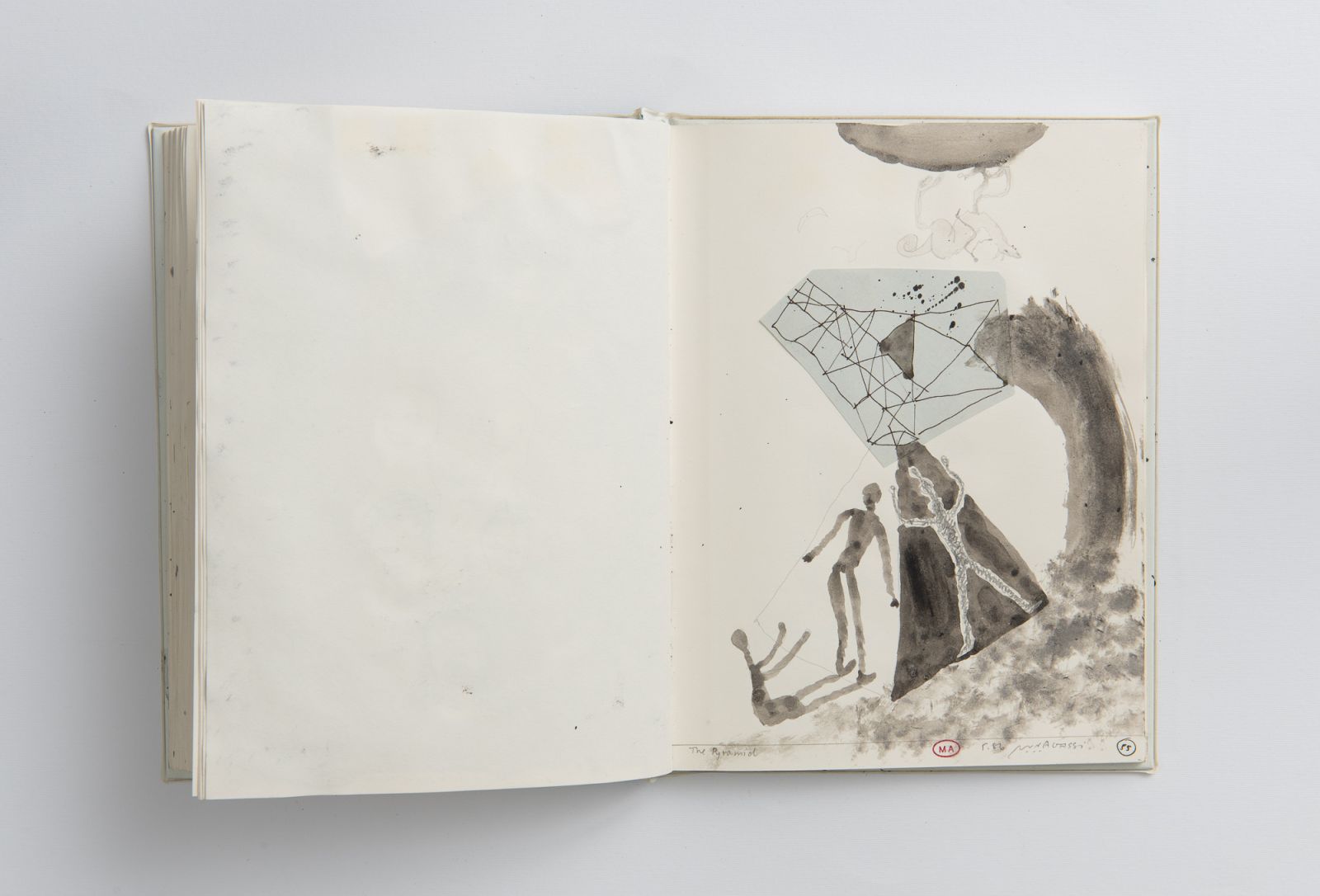

Demilitarized Zone

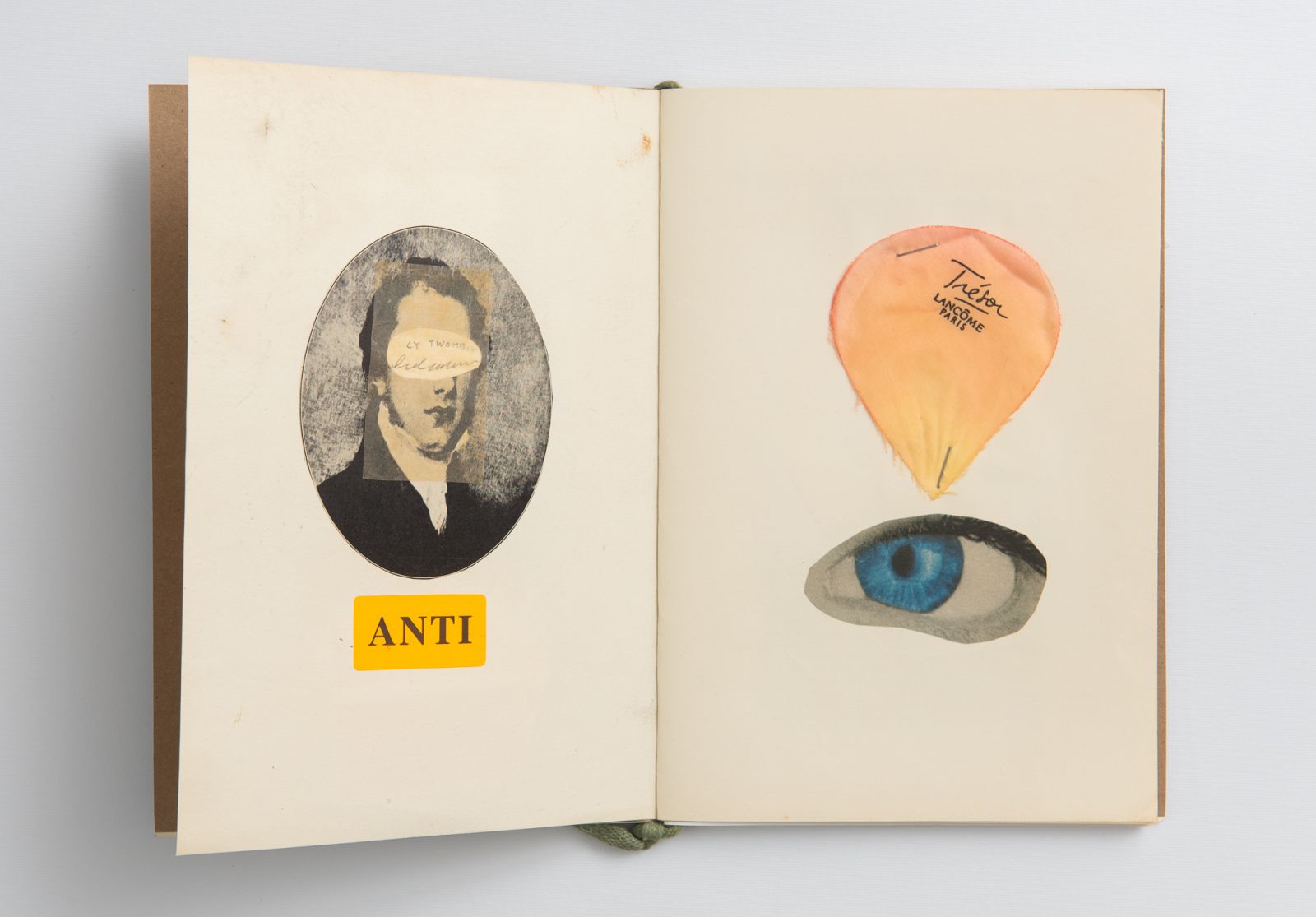

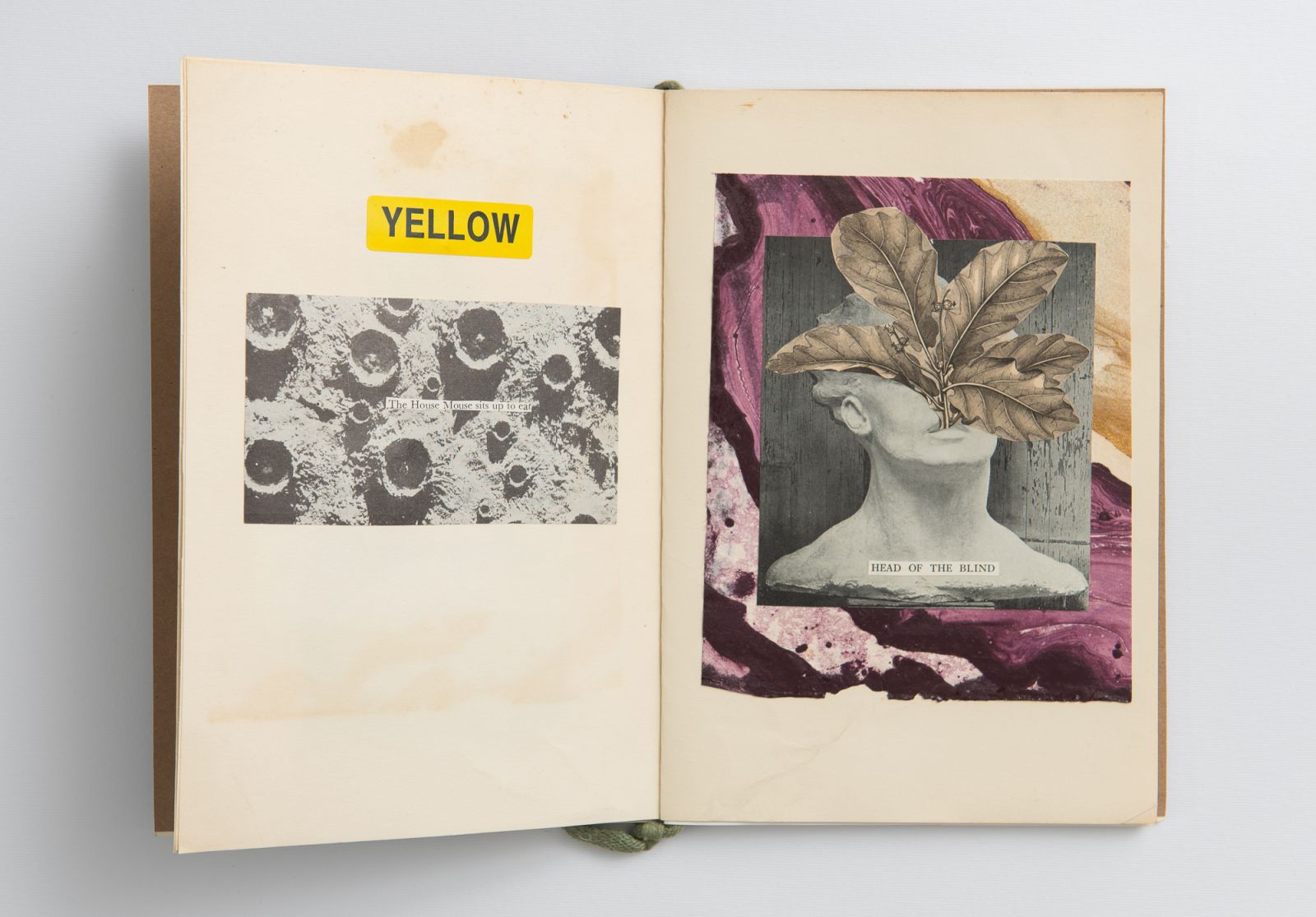

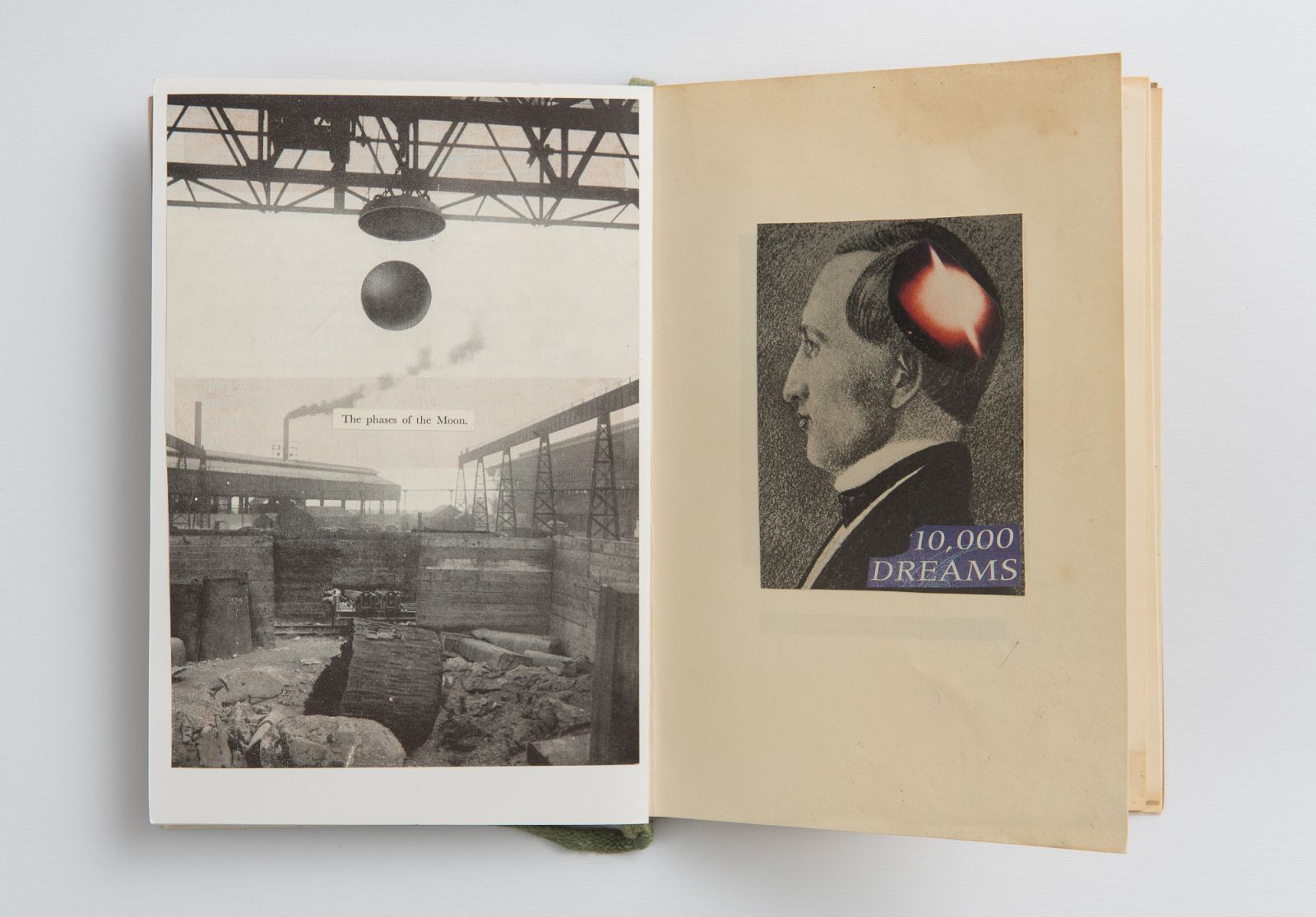

We touched on the matter of the disjointed, split self, the self that is not one, I want to look here at a double-page spread from Agassi’s Blue Book, an artist’s book or sketchbook from 1986. It’s a gorgeous object with a hand-made blue cover, and it seems Agassi made it in one stroke in May of that year. In terms of its material and medium, it contains in it most of the genres Agassi worked in – there are collages, lots of ink and pencil drawings, relatively few texts, which are much more present in other books. And alongside the multitude of visual languages, I think that every page is also very concentrated, and clean – a series of refined ideas.

In the first drawing I selected, there’s a schematically drawn figure with a small body and a very large head. Inside the head is a tangle of thin lines and another head, a kind of mask, and around it are ten similar mask-heads, and it is clear somehow that the main figure is throwing them up in the air, like it’s juggling the heads. Below is a title Woman Plays with Feelings. There are a lot of things here that repeat in Agassi: the phlegmatic demeanor of the figures who are drawn as if casually but with the confidence and flow of someone who knows what he is doing, in a kind of nervous flow, and on the other hand a scene of action and activation, of activity and passivity. There is something theatrical about these drawings of Agassi’s. And another thing that repeats and seems very fundamental in these books is the combination of texts. It often feels like an afterthought in relation to the drawing. How in one move, with this negligible title, he also tells us how to read the image – suddenly an emotional-psychological space opens up on the page, just by virtue of the tone of the linguistic statement.

We touched before on the space of the dream. This is a space that I am personally interested in in the context of Agassi. First, to find out for myself how much Agassi inherited from the surrealists, as part of his practice, regarding the self-immersion in dreams as spaces of work, how much he gleaned from them. There are dozens of dream descriptions scattered across his diaries and artist’s books over the years. I wanted to read this dream because there is something interesting here that might give us a key to his attitude on dreams:

“Last night I had a bad dream. I tried to push the dream inside a small box. Every time the dream disappeared the box opened. Every time the dream came back the box closed. Then I realized that this was a dream about Death. The realization came through the dream. When I woke up I couldn't remember the dream, only the little box."

Then he adds below –“So I made the dream up. But I’m not going to make the box.”

I wanted to underline three things here: one is how he writes the dream – he does not describe a scene, only the psychological, almost physical, mechanism of the action of the dream. It is a sculptural work. He does not reveal the content of the dream. Not the “why” this is a dream about death. I like the very concise form of conveying the dream, but from outside. The reader remains outside of the box. I don’t know what’s going on in there. The second thing is this twist. “So I made the dream up.” Now, as a reader, I don’t know if this whole thing is a report by an unreliable reporter. And actually, he has shown me a strategy of –

A writer.

Of a writer – who makes up things that did not happen.

Yes, it is a dream that is a Zen puzzle. So beautiful. It suggests that the space of the dream allows us to deal with finitude, with the knowledge that we are not in control, while we are not in control. This ties in to what we talked about at the beginning of the conversation, about looking at the archive from the outside. The act of putting things in order, putting things in boxes, is a way of dealing with the flood, with the split that comes back to haunt him. At the end of the dream, the imaginary order remains, the box, which can be grasped, but death, which disrupts all orders, cannot.

Yes. My experience with these books is one of unimaginable multiplicity. As you said about the archive, it suddenly seems to me that more than Agassi produced these artist’s books, he in some way lives in them. From the moment he announces the establishment of the Meir Agassi Museum in ’92, all the internal wars and the anxiety of influence get a conceptual framework that enables the plurality of voices. The museum as a literary solution, if you will. This is the greatness of the Meir Agassi Museum. The internalization that your inner territory is vast, and thus you can break through and expand the internal boundaries and limitations of the self. Therein also lies the tragedy of his project.

Yes, because when the internal territory becomes a demilitarized zone, you can say that the war is over, right?

I don’t know if it’s over. Bottom line, do you think he dreamt the dream?

And if we were to say yes?

The conversation is dedicated to the late Naomi Aviv, and is extracted from the book Meir Agassi: Was I Here? Gazes. Conversations. Thoughts, published as part of the exhibition Halon Lehalom Al Yoffi' (“Window to a Dream about Beauty”), curated by Yaniv Shapira and Orly Gal (associate curator) at the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod (March, 2024). Our deepest thanks to Yaniv Shapira, Nelly Agassi, Galia Bar-Or, Orit Segev, and the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod team, for making Agassi's books accessible on Madaf.

Edition of British first aid book, bandages, gouache, plasters, cellotape.

"This is the first book that spoke to me – it’s genius how he creates such a sense of horror. The more the book is bandaged, the more wounded it actually is."

Drawing and collage, ink, crayon and watercolor.

״My experience with these books is one of unimaginable multiplicity. As you said about the archive, it suddenly seems to me that more than Agassi produced these artist’s books, he in some way lives in them. From the moment he announces the establishment of the Meir Agassi Museum in ’92, all the internal wars and the anxiety of influence get a conceptual framework that enables the plurality of voices.״

Cardboard, photos from magazines, fountain pen.