You once wrote: “‘unrecognized’ is a state of mind that refers to a subject. Hence it is possible to ‘not know,’ but is it possible not to see? It is possible not to show.” Also in Bedouins, you went to know and to show the unrecognized, as you have been doing uncompromisingly for four decades. The project presents photographs and texts created during an extended stay in the unrecognized Bedouin village of Wadi al-Na’am in the Negev. How did the book come about?

The desire to live somewhere “unrecognized” arose in me 25 years before I went to stay in Wadi al-Na’am. I was looking to stay in an unfamiliar, out of the ordinary place – like a desert island – a place where you can just lie down and see what happens.

I wanted to understand how the incomprehensible concept of “unrecognized” translates into everyday life, what it means to live within a self-contradictory political concept. How is it possible that for year, a place exists, children grow up there who then also have children and it still isn’t recognized and it doesn’t appear on the map. Back then, I wasn’t thinking about staying as a photography project. I didn’t know if they would even allow me to take pictures, I hesitated whether to take a serious work camera or just a small camera.

The same month, the police began to demolish the unrecognized neighboring village Al-Araqib, repeatedly, and which has been demolished and rebuilt since more than two hundred times. Almost every morning I would go to al-Araqib, arriving there usually after the police had already demolished the makeshift structures built after that morning’s demolition.

I joined the residents in building the makeshift sheds for shelter. Sometimes I had to wait for them to bring the wooden slats and plastic tarps for building with, and then I would also photograph the demolition. Everyone took part in the construction: men, children and women would wander among the ruins and try to extricate any reusable material. It was the only place where I could see Bedouin women, photograph them and even talk to them. At night, I would join the men for conversation in the Shig (Shik). I drank copious amounts of coffee and water with them and they talked about their way of life and customs. I was introduced to a completely different and unfamiliar set of values than I had ever known, which left me confused. I left the trailer in al-Na’am at the end of August and returned to Tel Aviv, completely wiped out.

In your two previous books, and throughout your career in fact, you have persistently engaged with the same theme: “How does one fight against willful blindness? How do you force a person to see? He closes his eyes, and you demand that he “open them.”

Yes, I ask people to open their eyes, even though I know most of the time it won’t happen. But it is important to prepare the materials that will allow for opening eyes in the future, or any time. This is where the archive comes in, thinking not about the immediate, but rather about a delayed response. Maybe the archive will reach some future researchers whose eyes are open.

In the introduction you write: “I concentrated on documenting three unrecognized villages: Wadi al-Na’am, where I lived and over which hovered the threat of demolition; Al-Araqib, which was then being demolished and rebuilt almost on a daily basis; and Twayyel Abu Jalwar, which had been completely obliterated and of which no trace remained except for a doll-like scarecrow and a tent used by the residents who continued to graze sheep there. In Wadi al-Na’am, I saw the past of Al-Araqib and the future of Twayyel Abu Jalwar.”

To what extent is the motivation for “archive work” a consequence of your personal biography? Of personal foreignness to this place?

I don’t think that’s what it’s about, although I can’t deny the fact that for years I felt more like a stranger than a citizen of this place. This stems from an attempt to take advantage of the journalistic stage and subvert the principle of its immediacy. Why tomorrow? Why hope for an immediate effect? Why limit myself to the reader of the newspaper and not aim for a wider stage? Over the years I realized that I refuse to reduce the accumulated body of work to cardboard boxes with expiration dates written on them.

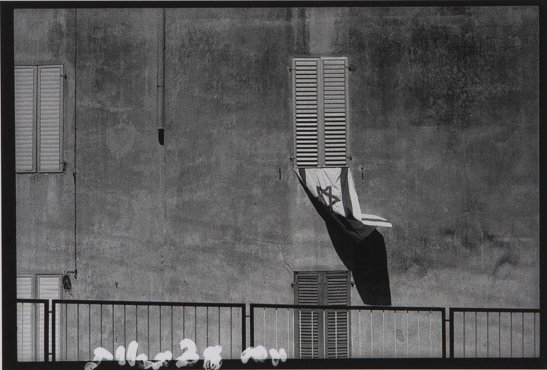

Anti-Mapping, your joint work with Shabtai Pinchevsky, is a continuation of your book Archive Worker and of your time spent living in the Bedouin villages over the years. According to the Tel Aviv Museum website: “The project regards seeing as a fundamental human right (much like freedom of speech, the right to fair trial, and freedom of movement). By changing the scale of the image, it enables one to visualize places that have ‘disappeared’ from official maps, both online and in print.” You photographed Anti-Mapping from above. You photographed Bedouins from inside the unrecognized places. It is easy to see that the projects complement each other in many ways. In Bedouins, how do you see the use of distance as a photographic strategy that you have dealt with in the past?

In the Bedouin project there was no real distance, or let’s put it this way: there was zero distance. The intimacy I was looking for during my stay there was not always possible, but I was using a camera that takes pictures from a very short distance, candid enough to allow the subject’s refusal to be photographed. Each photograph became a contract between me and the person being photographed. Anti-Mapping is a completely different story. Everywhere we photographed we asked for permission from the residents, but the people who noticed the drone are not visible in the photographs. It is a very technical work and our connections with the people photographed are not embodied in the final product.

We wanted to be like people who are part of a technical system for mapping and aerial photography. To enable a viewing option satellite photographs do not offer to the general public, but only to the “viewing authorities.” To think about the right to see through the definition of human rights, the equality of the right to see.

Bedouins includes excerpts from your diary. You write, for example: “There is a kind of loneliness that makes you feel longing, not only for the people you know and love, but for all the people you have ever loved” (page 31). It is a very warm, very personal, flexible and mind-bending book. Is it the coming-of-age of the political photographer?

It seems to me that even though at the time of writing I was living among Bedouins in an unrecognized village, the thoughts arose mainly from a very deep feeling of loneliness: you sleep in a junky trailer, it’s hot, most of the day you have no one to talk to, you go to bed at seven in the evening at the latest, get up at four in the morning and start walking. All in all, very little talking and a lot of time for thinking. This disconnection allows for reflection that is not possible in everyday life, and thus the mind summons faces and names from other times and places. I am not sure that this is the coming-of-age of the political photographer, to me it’s more reflexive, like a time of respite and internalizing of the political photographer.

On page 13 of the book you write: “As part of my work, ‘Targeted Killing,’ I took a picture with a telephoto lens of the village of Issawiya, from the vantage point of Mount Scopus. Among other things, I took a picture of a group of people who had gathered somewhere and were engaged together in an action, but I could not tell what. After scanning and enlarging the negative, I realized that it was probably a funeral. Is this a journalistic event? Did it become one because of what was captured in the photograph or will it be one if it turns out that the deceased is a shahid [martyr]? Was the photographer in the film Blow Up a photojournalist? Zakaria Zubeidi is the photographer, he is the subject.” How do you view the connection between “Targeted Killing” and the current project?

One of the things that fascinates me most in photography is the relationship between the photographer and the photographed, and the relationships that change over time. This is a very complex and unstable relationship. I change my role in every project; sometimes I’m a sniper, and sometimes I’m the forensics guy or the cartographer. In every project I redefine my identity and all that derives from it. Maybe this explains the connection between the projects.

Also, Zubeidi’s” wanted” poster was his first public portrait, and also “the first one that fell into the hands of those wanting to kill him” (Ariela Azoulai, Erev rav, 2012). How did you view the relationship with Zubeidi at the time? And today, in the current political context after October 7th? Just a few days ago the IDF killed his nephew, Muhammad Zubeidi.

At the time, I saw in Zakariah a fascinating phenomenon, with perfect Hebrew, sharp and charming in a way that if there was cruelty there, it was not present in my meetings with him. It was very confusing, but even when Gideon Levy (my colleague in “Ezor dimdumim” (Twilight Zone [a column that appeared in the Haaretz newspaper]) asked him about actions he was allegedly involved in, Zubeidi had very thought-provoking responses. Obviously I’m against any kind of violence, but in talking with him everything was blurred, the information about him didn’t fit the persona. During the photo shoot in question, I realized that I was just the messenger; it was as if he said to me, “Come show them what I look like.”

The events of October erase everything that came before, to some extent. We begin the count from zero, perhaps. I know Muhammad’s father, Jamal Zubeidi very well, (he would call him Hamoodi). We spent many hours thinking and talking about how we can live here in peace. I am well aware that the age of nuances is over. I am supposed to see Jamal as a monster and I refuse.

There are two peoples, two narratives that do not meet, two languages, and we are working on autopilot, especially when monsters enter into the picture, but not all of us are monsters. We are diverse, and it is not easy for me to say that, I try to see things this way despite a natural sentiment, and an almost innate hope for justice.

The decision to publish the book in Israel, in Hebrew and Arabic (with the option of English in some copies) is very impressive. I suppose it wasn’t easy.

No, but necessary. The thinking was not political; it was purely practical. Accessibility for its own sake. I thought about the possibility of making it accessible first and foremost to the Bedouin population, English was important because of the need to spread the word about the Bedouin tragedy wherever the book might go.

And how have you been since the seventh of October?

It’s been very difficult. We are having this conversation a few days after my aunt Ophelia returned from captivity in Gaza and I still do not know how she is doing. In a message she sent me, she mentioned that I was the last person she spoke with on the phone before she was kidnapped and that I had tried to calm her down. I saw Kibbutz Nir Oz a few days after the monstrous event. I walked around the burned houses, saw the archaeologists looking for what remained of the victims. I have a friend, Hayim Peri, who is still there, I feel for everyone, I refuse to say what is expected of me. The semester at Bezalel begins in a few days. I don’t know which students will return and in what state, how we will sit together in class, that’s how I am after the seventh of October.

As a teacher, activist, creator, how do you see the craft of making a book? How is it different from other crafts?

This is my third published book, until the Bedouin book I thought of books as another means of presenting works or perhaps translating a photography project into a book. This time, working with Michael Gordon has taught me to look at the format in a different way. Not as another stage, not as reflection, but as an object in itself. An independent object born to be a book, without there being any “before.” This is a new thinking and practice for me, maybe there will be more, I hope.

Who would you want to leaf through the book?

Everyone who went to a bookstore without the intention of buying it and suddenly happened upon it. And students: years after the notebook was completed I went back to it, I tried to read it not as a writer but as a reader. I found that there were some not fully-formed ideas there, so I thought it could stir something in young artists, something that would send them in their own direction, regardless of me.

Who is the book dedicated to?

The list is as long or longer than the book, family, colleagues, friends, but perhaps above all, those about whom the book tells a little, a very little, of their story.

What book should we add next to our library?

I always recommend the last book I read that still stays with me.

Passagère du silence is a book that has an element of instructions for use. Through the unique experience of the artist Fabienne Verdier, we learn about the importance of basics, of slow learning and listening. Elements and tools of learning that have become so rare, the importance of nuance and of restraint.

Where can readers buy your book?

The Asia Publishing website and in private bookstores.

Professor Miki Kratsman (born 1959) is an Israeli photographer, artist and human rights activist. He worked as a photojournalist for the Haaretz, Hadashot and Ha’Ir newspapers. He is an associate professor in the Department of Photography at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design and winner of the EMET prize, 2011 and the Ministry of Education and Culture prize, 2001. In 2015, the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York named him one of the 50 most socially committed photographers in the history of photography. Kratsman is one of the founders and currently the chair of the board of directors of the “Breaking the Silence” organization. In 2020, his book Oved arkhiyon [Archive Worker] was published by Kibbutz Hameuchad. The following year, his joint project with artist Shabtai Pinchevsky, Anti-Mapping, was presented at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

"I wanted to understand how the incomprehensible concept of “unrecognized” translates into everyday life, what it means to live within a self-contradictory political concept."

"In the Bedouin project there was no real distance, or let’s put it this way: there was zero distance. The intimacy I was looking for during my stay there was not always possible, but I was using a camera that takes pictures from a very short distance, candid enough to allow the subject’s refusal to be photographed. Each photograph became a contract between me and the person being photographed."