You are one of the first photographers in the country to have made artist's books. Back in the seventies, while you were in school, you were already experimenting with the medium, and to this day, you publish books in your own publishing house. How did your love affair with the artist's book begin?

It began when I was a student at Hadassah College in Jerusalem. I made a book dedicated to Tel Aviv from photographs I took at the old Central Bus Station (Houses, 1976). It was a coloring book. Then I went to study in London, which opened up a whole new world for me. The world of photography there was radical and exciting. I developed other work practices there, and made text-image works for the first time. It was my first attempt at what I called “primitive cinema” in book format. The London period was also a groundbreaking transitional moment from black and white to color photography. I made an artist’s book there about the processes of urban decline in the city center (Neighborhood, 1981), which consists entirely of color photographs. I have it to this day, even though the prints are very faded. Another medium related to books and photography that has occupied me since I was a child, is the postcard. From the beginning of photography, photographers have traveled around Palestine taking photographs and selling them abroad in the format of postcards. I collect postcards related to the Zionist project, and research how they were used as a means of propaganda in the Diaspora. Apropos of propaganda, the first photography book we had at home was the Album of the Decade, which was published in 1958, ten years after the State of Israel was founded. My father brought it home as a gift from his work. I remember it very clearly.

An Israeli’s Album contains fragments from your biography and also living nerves of an era. It’s a book that had a significant impact on the local field of photography in the 1980s and has since become a “classic,” as Dror Burstein stated in 2015, with the release of the second edition (see: Dror Burstein, “30-year-old Traffic Jam,” Haaretz, May 29, 2015). How did “Album” come about?

We returned to Israel in 1982. I didn’t want to come back. I began wandering around, not out of some motivation to make a book, but in order to touch down, to make friends with home. I would go on treks, sleeping outside alone in the field. I was thinking then about how small everything is here. One of the limitations of life in Lilliput is the lack of perspective. I tried to look from outside in, from inside out, to experience the space anew.

Things kept piling up, and as early as 1984, I had the opportunity to present some of the things I had done in the Journey exhibition held at the Camera Obscura Gallery. The space was organized in the shape of the Hebrew letter “ḥet” (ח) which is similar to three sides of a square, with a strip of photographs running along all the walls, like an enlarged contact sheet. People had to go on the trek with me. There still weren’t any texts like in the final book, only a short introductory text. This exhibition was recreated in 2013 at the Indie Photography Group Gallery by curator Jochai Rosen, and the late Galia Yahav wrote a beautiful review.

After the exhibition, I gathered the photographs into a dummy, with brief captions that only gave the name of the place. I made it as a tribute to the albums made in the late 19th century for people who couldn’t travel here or for tourists who would bring them back home as souvenirs. I used Kodak postcard-format paper, and pasted black-and-white photos into an old-fashioned postcard album, with the captions in pencil. This was the first mock-up for An Israeli’s Album.

I showed it to Yehuda and Muli Meltzer, who had the “Adam” publishing house. They were already committed to Joel Kantor (see: Pictures from the Land of Israel), and didn’t want to take the risk of publishing two photography books in the same year (1986). This forced me to take a step back and figure out what I was going to do. After meeting with them, I set out with the understanding that I would make the book without thinking at all about the target audience, but only about my authentic experience, and not let any considerations about reception determine the work.

Album was finally published in 1988. What happened during those two years that made it the singular document that it is?

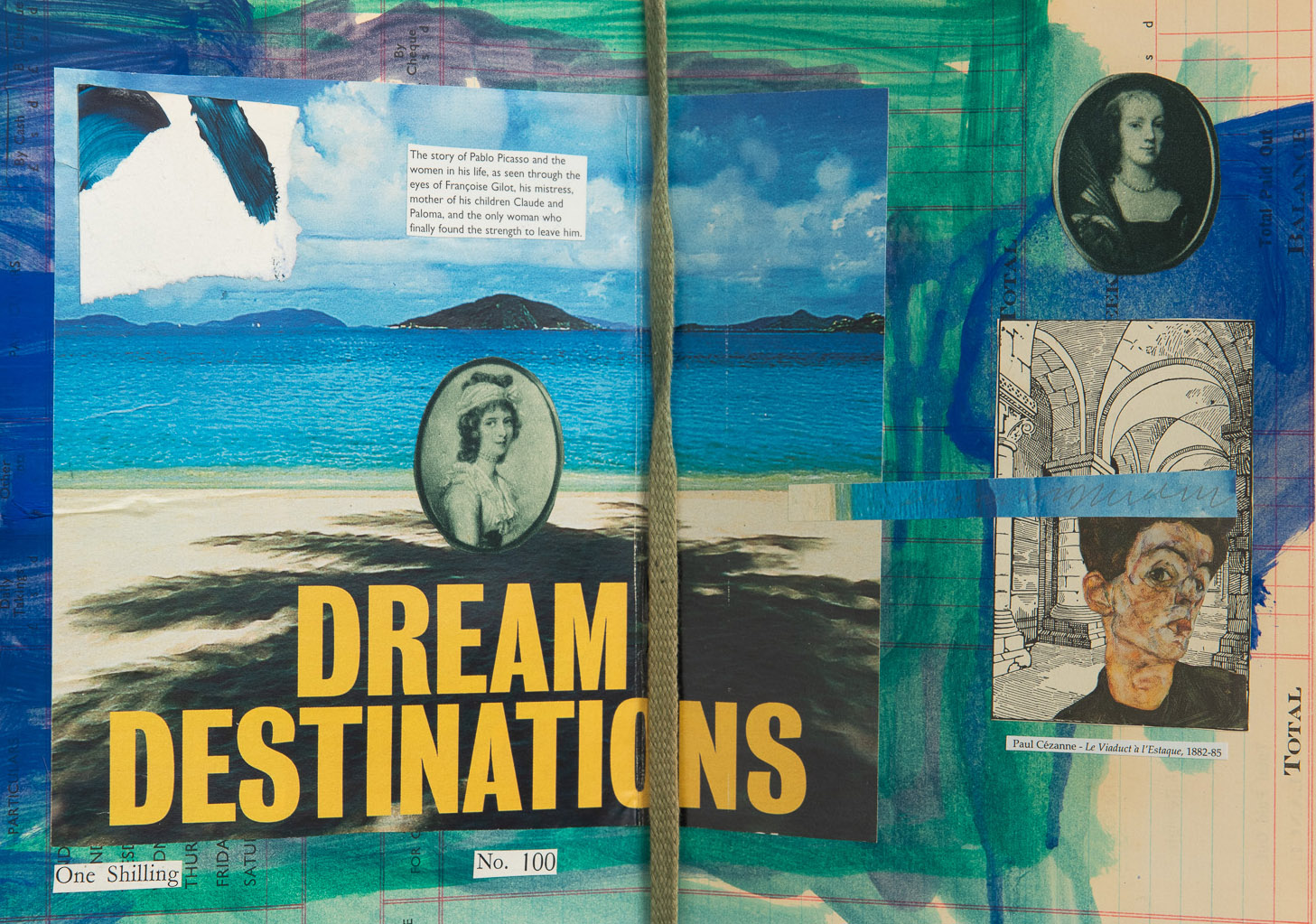

The significant change relates to the ratio between text and image. When I was studying in England, I discovered scrapbooks. These are do-it-yourself books that combine visual and textual materials, and unlike sketchbooks, which are intended for sketches and drawings, they’re sort of thick notebooks, usually with a black binding, in which you can paste newspaper clippings and pictures and also write and draw in them. I started using this medium in London, and the books became a portable studio for me. My archive already has over 60 scrapbooks from my 45 years of creation. At that time, I was “writing photos” inside my scrapbooks.

What do you mean by “writing photos”?

Many times, I took pictures, and the result didn’t express what happened, because of technical failures or because of the limitations of translating a complex reality into a visual outcome. So I wrote in words what hadn’t been captured in the photograph. When I started reviewing the new version of the book, I realized I was going to use these texts. Once I made room for the words, significant moments from my life floated to the surface, from the time even before I started holding a camera. I’ll read a childhood memory aloud to you: “My mother got off the number 5 bus, and came home pale. On the bus she had seen, for the first time since the war, the Jewish kapo who had betrayed them. She shouted and cursed at him. The people on the bus were silent, and the man got off at Dizengoff Street” (p. 48).

You turned this text into a “blank” spread, and there are other blank spreads in the book. Leafing through the book for the first time, it looks like a printing error.

Yes, another blank spread relates to the Yom Kippur War (also known as The 1973 Arab-Israeli War or the October War), and it has only one sentence: “Once the whole thing starts, you hear nothing. You only see a rain of fire and the seeds of thorns floating in the shock waves of the explosions” (p. 38). I surprise myself reading the text to you now.

What are you surprised by?

By the emotional distance I created here. It’s a description of dissociation. I write about silence at the time I’m under shellfire, watching nature as the earth shakes. The empty spreads create an open valley, much like trauma generates a rupture in the narrative and spaces in memory.

Tali Cohen Garbuz wrote about your work in the context of military post-trauma as a prism that allowed you to mediate between private and public trauma, but also created a disposition of foreignness and “partial incomprehension” (see: Tali Cohen-Garbuz, A “Supermarket Cart Alone, About the Photographer-Artist as the Observing ‘Other’: The Case of Shuka Glotman”). When did you realize that you have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?

In 1997, I met the head of the then Combat Response Division, Yaffa Singer. She diagnosed me immediately and said, “You tell the story so poetically, and it’s a terribly pathetic story.” And then, I hadn’t even managed to leave the checkpoint, when I saw in my mind a door with a sign that read: “Here live happily Mr. Poetic and Mr. Pathetic,” a line that became the title of my solo exhibition in 2000 at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. It took me six months after meeting with her to contact the army's Rehabilitation Department.

That’s no coincidence that it took me so much time to come to terms with my injury, as PTSD related to war in Israel was a taboo in the public discourse for decades. Only a year after the war, I wrote and published a text called “Just Like Always” (Maariv, September 13, 1974). If I could have gotten to treatment in real time, my life would probably look completely different.

Apropos of Tali’s text, I think the transition from the collective first person to the individual first person, occurred in most of the people of my generation, see the works of Joel Kantor, Oded Yedaya, Micha Kirshner, Avi Ganor, Boaz Tal, Ronit Shani and more, after 1967. And it’s interesting to see how private experiences have affected the political consciousness, its maturation, singularly with respect to each and every one of them.

You mentioned Joel Kantor, and that’s a fascinating comparison because his In Our Image and your An Israeli’s Album are both black-and-white documentary photo books, with similarly sized images and pages, but at the same time, they’re completely different. His book accumulates by visual means and simple location, in the likes of Robert Frank’s The Americans. While both books are proposing hooks for the understanding of a zeitgeist of Israeli society, in the syntax you create, you force the reader either to fill in the gaps between the text and the image from their personal experience or to encounter the inability to fill them. Your texts are sometimes a personal story, sometimes a description of a situation, and sometimes an anecdote that is difficult to decipher. The texts complement, interpret, and contradict the images. How did you work on this “partially understood” syntax?

I moved the texts to small index cards, and I had a pile of 18 x 13 cm proofs. I would sit and play as if I were playing “cards,” pinning pictures to cards. Playing, swapping them out, studying the editing and potential connections. The longer you look, there will still be surprises. For example, now that I look at what comes before and after the blank spread about Yom Kippur: there is a photograph before it of the resuscitation dolls that were displayed in an IDF exhibit done during the Lebanon war to raise the country’s morale.

The next photo is of cadets in an artillery corps in a formation at the foot of Tel Fares in the Golan Heights. The text, on the other hand, speaks of a situation that occurred in late October ‘73: “After it’s all over, we arrive there with his father to look for some sign in the empty field. Maybe something was left there. After hours of searching, all we found was half of a dog tag,” (p. 39). Incidentally, the dog tag we found didn’t belong to his son.

And unlike Joel, you insist on not writing the names of places.

There is a very beautiful book edited by Ronit Shani called Ir Hama (Hot City). At the time, I showed her a selection of photos. She chose what she wanted, and then asked for the locations and dates for the photos. An argument between us ensued. I insisted that I don’t create historical documents. For example, the photograph of the child with the dove (p. 12) could be in Maalot, Migdal Haemek, or Kiryat Gat—where it was actually photographed. It could have been photographed in any place we then referred to as “development towns.” I’m not committed to a history of dates, I’m committed to an experiential history. And the same is true of what we call “Israeli experience.” This logic is maintained in all the books I did afterwards.

This is interesting with respect to the Journey exhibition, which you described as a contact sheet without text. With a contact sheet, which is ostensibly an entire array, there are jumps between times and places. In fact, it can be said that just as there are 36 images in a contact sheet, there are also 35 gaps.

Photographers, certainly those my age, lived in capsules of 36 photographic opportunities. Looking at a contact sheet was profound because it allowed you to understand where you are coming from and where you are going. Every time I pick up the camera I look at what was in the previous contact sheet, what was the last photo I took, and find that there is a connection, which isn’t entirely conscious. We live in a “movie” that is larger than what our consciousness can contain.

In working with students, in the first lesson, I send them to find three photographs: the first photograph they were photographed in, the first photograph they lived with—one that was in their home, usually a photograph of those no longer with us, and the first photograph they took themselves. These are the most important coordinates for a person living with photography. You discover that nothing is accidental. We’re directed towards a certain path, and the wisdom is to discover it, to be in dialogue with it. It goes beyond editing a book. It’s about giving meaning to your day-to-day life. You live your life, even when there is no invitation from the outside.

If we go back to the Album, then the editing process was replete with the meaning-driven experience that I’m talking about, and it develops along two axes: the vertical axis between the images and the texts, and the horizontal axis, which is between the images themselves, and the texts themselves. The book as a whole can (also) be perceived as a dialogue within my divided consciousness.

That’s fascinating, because apropos the cinematic aspect, it’s a bit like watching a foreign film with subtitles or vice versa. At the time you made the book, it was really a radical act, and then you even dared to call the book An Israeli’s Album.

A few things in light of what you said: When the book was published, it didn’t resemble anything on the Israeli bookshelf. My source of inspiration at the time was Wim Wenders’ early films, in black and white. He would set out with a cast without a script and things would just happen. After all, he was a stills photographer with a deep understanding of what a frame is. Imagine an actor sitting somewhere and in the frame behind him all sorts of things happening randomly, for example a woman hanging laundry, a child racing by on a tricycle.

Everything is connected and not connected, at the same time. That really resonated with me. There’s one more thing worth noting in this context: We live in a very small place. Everyone can identify places even without the name being written. By the way, this is a big obstacle for creators of feature films. Let’s say you go see a film and they filmed it in a place you know; it can detract from the narrative experience. It’s a problem that’s unique to here, and certainly for people who are on the move like me.

One last question about the text, there are frames on which you chose to write on the negatives themselves, that is, to “fix” their connection to a specific word. Can you elaborate?

While I was working on the book, I had an exhibition in Hamburg called Footnote. Preparing for the exhibition, I looked for photographs that, for me, are the cornerstones of the “Israeli experience.” I took a permanent marker, and in a dark room in a completely spontaneous way, I wrote on the negative. The subject of text and image is endless. After all, as children, we see before we read and write. The cultural construction of the “word” distorts this natural order. It’s very difficult to see and photograph in a manner that’s free from the textual structures of language; we see stories and anecdotes after we experience patches, color, and texture and so on. I try to think of a text as “ready-made,” to think of it in a plastic manner. Most people shy away from expressing themselves writing, for fear of literary pretension. I approach text as a plastic artist. I don’t have any pretenses of being a writer, I use words.

For example, the photo I wrote the words “Light Line” on, if you look at it closely you will see that it’s a photo of an air force aerial demonstration. I wandered around the vicinity of Sheikh Munis—a Palestinian village whose residents were expelled in 1948—where the Tel Aviv University campus is located today, and photographed a wall on which this framed photograph hung. If you look closely, you can see the scratches made by time. Back then, there was a lot of Israeli pride, in both private places and government places; in steak shops, offices, car garages, the Social Security office, and private homes. I debated whether to include some of the frames with the captions in the book. In the end, I realized that they belonged.

What was the deciding factor? And more generally, what was the criterion for the photos that went into the album?

First that they had to be full-frame. In the first edition, you see that all the prints include the frame of the negative. That was the challenge of the analog photographer: no cropping. That was the tradition of documentary photography I was connected to. There were good photos that didn’t meet this criterion and therefore didn’t make the cut. It takes us a long time to say goodbye to easy and casual loves. As a photographer yourself, you’re probably familiar with it: you walked around a place, something stopped you, you snapped the photo and came home satisfied. Enough time must pass for one to be able to look at the photograph as if it had been given to you by a stranger. Editing takes time, and it is critical that an image be static, printed, and a material object when looking at it, not like today, on screens. The more we separate ourselves from the event photographed, which involved all five senses, the more we can understand whether the result stands on its own or not. I looked for this cleanliness in the edit.

Were there elements in the book that evolved in your work over the years? For example, I’m thinking of the photograph of the “Sabra mask” (p. 10). The eyes have become a kind of “trademark” of yours used in plastic works and collages. This photo also became the cover of your 2006 autobiography Live Photography.

That’s interesting. I didn’t think of the “eyes” motif in the context of this photograph. The mask is a ready-made I found on the site of a scout camp at Hotem HaCarmel. I used my hand to cast a shadow on it and took a picture. The sabra, khabar in Arabic, appears in many of the photographs I have taken over the years. Once, people would ask, “Are you a Sabra (a native-born Israeli)?” There was a hierarchy in my generation between those who were born here and those who were not. Politically, much has been written about the khabar as a symbol of the Palestinian “tsumud,” the attachment to the land, and also about the appropriation of this symbol by the Jews who came here even before 1948. Did this skull from a cactus become the eye, which is also a leaf, fish, lens, spearhead? I can’t say.

I do know that the shape of the eye allowed me to bypass a limitation, as I don’t know how to draw. I made stencils of it, which serve crutches for me. They have appeared in my works since the late ‘80s. What are the qualities of this shape? For me they are organic qualities. I borrowed this form from a schematic illustration of a description of human sperm.

Interesting. Perhaps these eyes are an attempt to look into the eyes of a “stranger” or a “witness” looking at this place.

In hindsight, I can say that one of the fundamental things in my work as an artist is my attempt to be a “witness,” to capture the zeitgeist. In this sense Album captures elements of this place, as they were and have been preserved from the 1940s to the 1980s, elementary things, on the level of textures and the spaces.

When the book came out, Meir Agassi wrote a wonderful article where he called you “The Rust Hunter.” I’ll just quote one sentence: “Without our acknowledging it, and perhaps without our knowing it, objects and things and spaces awaken in us strange dark feelings of mental chaos.”

Agassi understood the book in a profound way, he wrote about it before we met. Look, this book, like the “Israeli” place, is a collage with rough stitches. The more you try to tame it, the wilder it gets, the more abandoned. It’s become more crowded here, but “the experience” for me is what used to be called “partatsch,” commotion. There is no planning, and even if there is, it isn’t implemented. The word partatsch pales in relation to the real thing. This isn’t a “quality” you choose. For example, on Shomron Street near the Central Bus Station in Tel Aviv, there were makeshift shops in dilapidated and temporary structures made from wooden shipping containers, that raked in millions, and parked next to them were the owners’ Mercedes. This apparently came from the mentality of the ghetto, there is no need to invest in the long term, because everything is temporary anyway. Here today, gone tomorrow.

Let’s go back to the time when there was a “dummy” for a book, but there was no publisher. How was the book published eventually, and how was it received?

I decided to meet with everyone who worked in publishing in the country. I had 60 meetings. It was an informative lesson, I was really obsessed. I also thought about the possibility of publishing it on my own, but in those days it would have meant an enormous outlay of money. I enrolled in an excellent Labor Ministry print production course, which gave me a solid foundation. I created two dummys, and brought them to meetings. At that time, I was already teaching at Camera Obscura, and I was friends with Aryeh Hammer, who was then the director along with Oded Yedaya. Aryeh wanted to publish the book, while also publishing Oded’s Personal Document, which I think presents him as a photographer at his best. No one wanted to take the financial risk for the first edition, except Aryeh Hammer.

Fate had it that in 1987, Camera Obscura invited Robert Frank and Allen Ginsberg to give a workshop on stills, film, and poetry. I showed them both the dummy, I had an English version then that I was not sure about. Ginzburg saw the book and told me “You’ve written a haiku.” I wasn’t familiar with Japanese literature then. He gave all the workshop participants these sort of Xerox booklets with haiku poems, which he wrote during his wanderings in Tel Aviv. He gave me an amazing writing tip: He always said, “Read the texts aloud, if breathing gets disrupted, something’s wrong.” The tongue and the breath never get confused. I later sent Frank the book, and he sent back a postcard in which he wrote warmly. To my delight, the first edition of the book completely sold out

The first edition was published in Hebrew, with the texts translated into English and appearing as a list at the end. In the second edition published in 2015, you made the book bilingual: with the English above the photographs, and the Hebrew at at the bottom.

Yes. I worked on the book with Doron Dekel who in 1988 was a fourth-year student in the Graphic Design Department at Bezalel. In 2015, I found him again and he designed the updated version for me. I was lucky enough that in 2015 Yuval Bitton curated the Drive-In exhibition at the Ashdod Museum, which was a tribute to photographers of the 1980s. He invited me to exhibit An Israeli’s Album, and I presented the images in the sequence of the book, similarly to the Journey exhibition. The museum funded the scans of all the negatives, so I was able to dedicate myself to the production of a second edition. I decided to add five color images, and six new texts. I published the second edition with my publishing house, Me’ir – Publishing House – Abirim. Over the years, I realized I needed my own publishing house.

I always say the title of a book is like a secret. Will you let us in on it?

The word “album” for me echoes the victory albums, as well as the family album. One of the things I learned about the Zionist propaganda books was that at that time there were people whose family albums had been lost on the roads and in wars, and for whom the state albums were a kind of substitute. You can see in the Jewish Agency for Israel's albums, photos of couples who got married without mention of their names. The same photos could have appeared equally in a family album. Both are tools for identifying with heritage. The title Israeli Album in Hebrew is of course ambiguous, “An Album of Israel” and an “Israeli” album. That duality is lost in English.

How do you see the book today, from the perspective of more than 30 years?

The insights I worked with in 1988 have become even more clear, sharp, and real. Then and now, I wasn’t trying to be radical, I was trying to be communicative, to move the reader through identification and experience to a place of dissonance. I was not looking to be provocative. The book has emotional moods that if while reading they awaken in you, the possibility for a new understanding opens up. I think the occupation has become more brutal, crude, and overt. The second edition ends with a sentence: “The entrance floor is dark now and abandoned. The push of a button quickly resets the flickering digits and the door opens. Inside the empty elevator, a black umbrella stands in a puddle and next to it a silent aluminum suitcase. It’s time to go.”

Since An Israeli’s Album, you have made over 10 artist’s books. At the end of April 2021, a new book of yours came out, bringing together more than 35 years of photography of the Lag ba’Omer celebrations on Mount Meiron. You also send great newsletters to those who are lucky enough to be on your mailing list. What camera do you photograph with today?

With a new cell phone that my wife insisted I get. The cell phone takes me back to photography as a child. When I was nine I got a Kodak Brownie 129 camera, which just needs a click and there is no control over parameters. With age, I return to the initial experience of being “transparent,” of working simply. I have a book called Jerusalem Beach, of photographs I took using the dumbest plastic camera there is, that I got when I bought toilet paper at the supermarket.

Making a book is like. . .

It’s complex ... it’s fun … and if you do it slowly, you learn a lot.

What book should we add next to our library?

The late Boaz Tal had very unconventional publications.

Where can readers buy your book?

On my website and by email: glotman53@gmail.com.

Yehoshua (Shuka) Glotman was born in 1953 in Tel Aviv-Jaffa and lives and works in Abirim in the western Galilee. He is a multi-disciplinary artist, curator and teacher, and is also a facilitator for Israeli-Palestinian dialogue. Glotman studied in the photography department at Hadassah College in Jerusalem and the University of Westminster in London. His photography, photomontage and video work relate to the Israeli reality and its unique inter cultural situations. In 2015, he published a second edition of his artist book An Israeli’s Album, first published in the 1980s and became a cornerstone in the field of Israeli photography.