You’ve completed four books in the last decade. You could say that each one is a kind of landmark, and they’re all related in one way or another to an exhibition, but they’re not exactly catalogs. How does making books relate to your practice as a photographer?

[Ana Yam]: For me, but perhaps also for many other photographers, the first exposure to photography was not through an exhibition, but through the family album, photography books, and magazines. There is something about these formats that is very natural for photography, even more than the gallery space. Editing and thinking about sequences have always been a dominant element of my work, whether with my own photographs or those of others. I am addicted to the act of editing, and books focus me on it.

What is the difference between a book and an exhibition for you?

The exhibition includes considerations of size, the way in which the image becomes an object, the movement of the viewer in space, and viewing distances. The framed photograph is more alienating. I also really like the coldness of the medium, I wouldn’t abandon it, but a book allows for a warmer experience. You can caress the images and not just look at them, you can get into bed with them. In a book, we mostly look [at the images] alone. It’s also a more cinematic experience, which is very interesting to me.

When I was doing my master’s degree at Bezalel, I wanted to make a book as the final project. I started working on an artist’s book, which in the end didn’t happen and the book came out a year later under other circumstances. Instead, I worked with a slide projector. For me, it was an intermediate zone between an exhibition and a book. In this work, there were two projectors that projected photographs randomly side by side. The light became material, you could almost touch it.

Can you describe how the books you’ve done so far led to the current one, OLYMPUS?

The first book, Anna Yam, came out at the same time as my first exhibition at Braverman Gallery, which was called 22:22. The book brings together a group of works from several exhibitions I did at that time. It mainly has my photographs and some that I found, which were an opening to the practice of using images that aren’t mine. The second book, Bird’s Milk, was published as the catalog of my solo exhibition of the same name at the Tel Aviv Museum. It also contains a number of ready-made images, which I didn’t take.

I published the booklet 43:209:02, when Merav Katari invited me to do an exhibition in the Lexus showroom. I collected all the photographs from family albums of people I knew, all immigrants from the former Soviet Union. The latest book OLYMPUS came out at the same time as the exhibition at the Ashdod Museum, curated by Roni Cohen Binyamini. There everything was completely the other way around. The entire book consists of images from a large image bank that I built from family albums. One could say I move between engaging with direct photography and appropriating photography in various degrees throughout my projects.

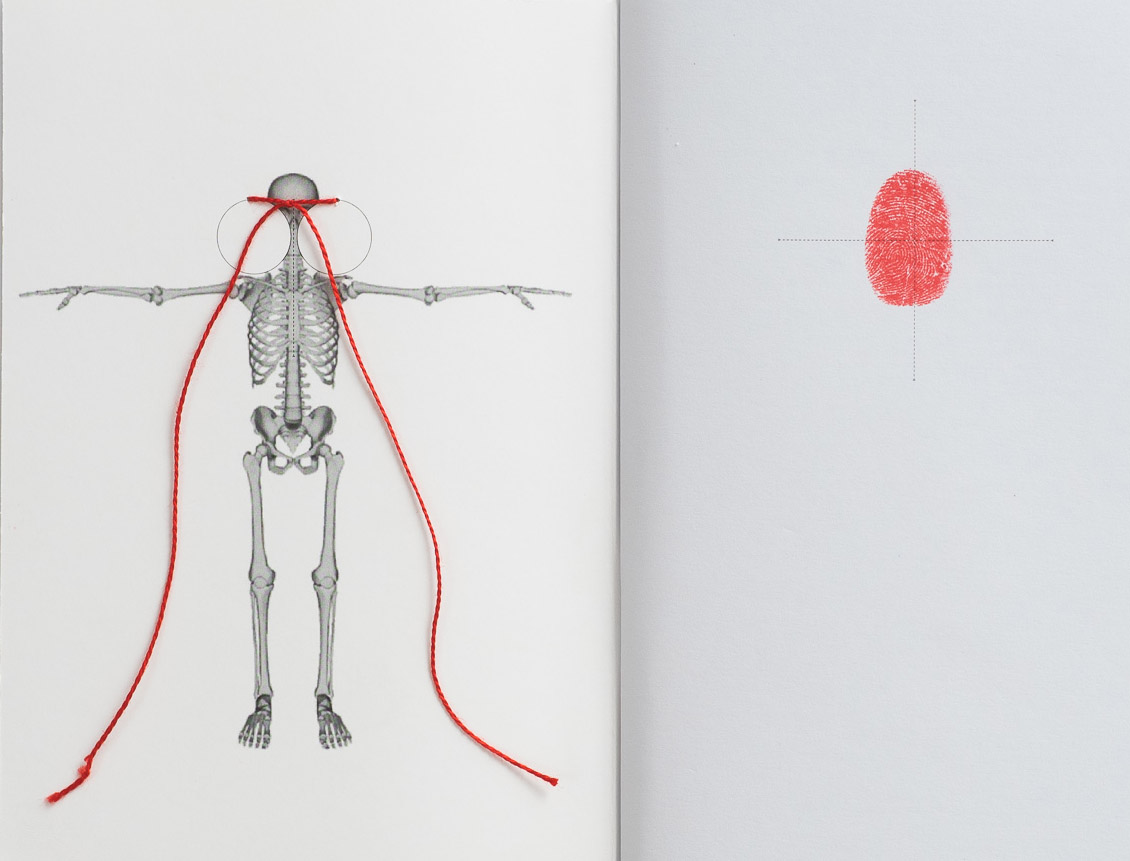

In the book OLYMPUS, you don’t include your own photographs at all, but there were in the exhibition.

Yes, they were structured as two separate projects, the book actually slightly preceded the exhibition. The exhibition opened when Adam, my second son, was 7 months old. Because of its compactness and portability, I could also work on the book while I was on maternity leave, with a baby draped over my shoulder. I wanted it not to be clear what you’re seeing when you open the book. Is it raw material, or something in process? It’s not a translation of the exhibition into book format, and clearly not a catalog of the exhibition. The pulse of the book and the exhibition are also different. It has its own vibe. My books almost always start with images, not with texts. It’s a principle for me. There is something strange in Israel, the art books are always wrapped in texts.

When did you start collecting material from other people’s albums?

I was always collecting materials, just waiting for the right time. It started from photographs I would take while visiting family. I would look and steal a photograph, scan it, return it, or forget to return it. Many were angry with me that an empty pocket was left in some album. Even with my father in Russia, I would open the albums and take. The non-artistic photograph is very interesting to me generally. Afterward it became more conscious, I would go here or there, to some other relative. While getting a manicure I would ask the manicurist if she had any photos, or the clerk at the bank.

When I would come to people’s homes and look with them at albums, some of them stayed with me while I looked, some left me by myself. Most didn’t understand what I wanted to do with them. And really at first, I didn’t know what would come of it. Sometimes I would come with a camera, and make hasty reproductions then and there.

It must be interesting to see how people keep their family photos today.

Absolutely. Besides my desire to create this image bank, according to some very abstract and associative code, it’s a study on the relationship to photography, an unwritten study. There were those who had it cataloged years ago according to some order they remember, and then there is the jumbled cardboard box. One man said he had a bag with 15 photographs, and that was it. “I didn't take pictures,” he said. Their attitude towards my gaze also interested me. There were people (mostly men) who desperately wanted to explain to me what we were looking at. It was clear to them that the images didn’t really tell the story, and there was something heartbreaking about it, the way they tried to transcribe the photograph, to penetrate its facade. There were others who said “photograph it, take it, and do what you want.” Those who dived in with me were trying as if to reorganize their memories, to organize their attitude to this black box.

It was sometimes very strange. It’s very intimate, almost psychoanalytical. The “album” in all its forms, is like a derivative of the human being, which shows also changes that have occurred over the years. Body language, then and now. A husband and wife in pictures, then the husband is gone. The dilemma of whether or not to ask, where is he?

And the stories themselves don’t actually “enter” the work itself. You recreate a sequence, a kind of new huge family album of the Jews who immigrated to Israel during the 90s from the former USSR. What’s it like to be a photographer-editor?

Making connections is something I do all the time. In some respects, I’m more of an editor than a photographer. I always have this fantasy that my double goes out to take pictures, and I get to stay in the studio and edit. When I photograph, I artificially try to detach myself from my “goals” or “motivations.” To enter a wild, free zone. Usually, I deliberately postpone the moment of photography, the development, and the moment of observing. The images come to me when I am already disconnected from the experience of photography. Sometimes at the moment of the click of the shutter, there is a strong feeling that “something big will come out of this,” and usually there is nothing there. I don’t remember what happened anymore. There’s some vague feeling that remains. So there is already a gap between the photographer and the editor when it comes time to make the connections.

How did you work on sequences? You had hundreds of photos.

In OLYMPUS you see cars, windows, and plants. I try to keep the editing system moving, inside-outside, near-far, and hot-cold. The visual structures encompass the psychological structures and hold the meanings within them. The essays can sometimes be jarring, narrative, psychological, or even humorous. I try for the “whole” to not be clear, like an EKG, it starts as something and continues differently.

I started seeing patterns, and clichés. Like standing near trees, on top of mountains, in the supermarket. The first group that took shape was the photos next to cars. This isn’t something that is typical only for immigrants from the Soviet Union, of course, but here it’s a specific pride. The car symbolized freedom of movement, a connection to the West, and a status symbol. It’s important to know how to drive, just like it’s important to know how to swim, to ride a bike. A survival instinct, you could say. This series became a booklet that preceded OLYMPUS.

There is something almost opposite about these photographs compared to magazine photos of cars or even images from the American culture of race cars and girls in bikinis. It reminds me of Rineke Dijkstra’s series of girls and boys on the beach. The shyness, the attempt to meet some standard, which inherently leads to failure.

This is a nice link. In psychology, the age of puberty is sometimes called the age of migration. The teenagers in these photographs are also in a period of transition, growing up. They’re migrating from childhood to adulthood. And the adults actually look like teenagers too. There’s a strange innocence here. They are amazed. It’s disturbing, and also confusing, where are they going? Where is there to go? They seem to be asking, where am I actually?

There is a photograph of my mother here with bleached blond hair. She’s posing next to a car, and it isn’t even our car. And what about this, today at 5:30 in the morning, my two-and-a-half-year-old shouts “steering wheel steering wheel.” And there was nothing else to do except go downstairs and sit with him in the car at the steering wheel so that he would calm down. Roland Barthes has a very beautiful text in which he admires the newly released Citroen. This is such a powerful archetype. I don’t differentiate between Citroen and Subaru whatsoever.

It literally feels like a limbo of several time intervals mixed together in this book. The colorfulness of the photographs also creates a feeling of “not quite from here,” and then suddenly you recognize the views of the city of Haifa. How is “here” depicted in this work?

In the albums, I looked at it was clear what was “here” and what was “there.” They not only “celebrated” this place, but they also celebrated the medium, crafting the family album of “here.” Like a long trip to an exotic place that is worth documenting. Itamar (my partner), always says about my childhood photos, that I look like his grandmother’s generation. It’s not only because of what you see but also because of how you see, and how you photograph. For me, despite the fact my gaze is a hybrid between here and there, my first images were taken here.

Dr. Orli Shevi [from the Faculty of Art History at Tel Aviv University] gave a lecture on OLYMPUS, and compared it to images from the pioneering history of Israeli photography, especially from the 1940s. It is amazing to see how patterns of photography are reproduced from one period to another and have a similar look, from the level of composition to the placement of a leg, or of a hand. It doesn't matter that there is a 90-year gap, there are gestures that are engraved in collective visual memory.

It is interesting because OLYMPUS is a pioneering project itself because it examines the Zeitgeist of a whole generation. The pains and gains of moving to this country, in a very straightforward way. It reminded me of my grandmother, who emigrated from Russia to Israel after World War II. Her house was like a time capsule up until her last days, floating in another place and time. Do you see something from this “time standing still” reflected in your parent’s generation as well?

My parents were younger. They opened the windows, there are no more heavy carpets or drapes hanging from the ceiling. Most immigrant houses looked as if they hired the same interior decorator. Clean counters, everything in beige, integrated kitchen. The excitement from the “new,” like in the photographs in OLYMPUS there are lots of skyscrapers. It’s a naïveté that arouses some discomfort.

You guard and challenge this capsule at the same time.

Subversion through conservation, yes. OLYMPUS seems to want to impersonate the “Family of Man.”

One feels this very strongly through the letters you included in the book. For example, a letter from a guy named Yevgeni, who is writing to his parents.

Yes, the letters are a bit like the photographs in the book, they are representative. They have the same refinement as the family photo, they are concise and visual. He’s as if trying to sculpt the space, to convey a maximum of information with a minimum of words. There is no sentiment, just a description. For example, the short text, which was actually written on a postcard, in which he describes the texture of an avocado, its color, tries to be accurate. This is a transcription of a first glimpse of a place.

He describes the kibbutz, the dining room, the amount of fruits and vegetables. It really interested me in the context of this immigration, the wonderment from the food. There is a section in there where he describes walnuts, and he says that here they are darker and longer, and their shell is soft. He’s basically describing a pecan. And the funniest thing is that the guy who wrote it, after all this pioneering, left after two years for Philadelphia. He’s been there ever since. When we arrived in Israel, we went to see him, and in the kibbutz, I gobbled up pomelo, and I got a rash all over my body. One of the photographs that were the key to this exhibition is from this kibbutz, Beit HaEmek. A photo of me standing on a diving board.

What were your inspirations for making this work?

One of the first books I remember seeing was a catalog of Czech photography at my grandparents’ house. It was considered Western art. I lived in Yokneam Ilit, and when I was in the army, I bought a book by Will McBride in the mall. It’s a very strange book with a lot of children’s nudity that was sold at Steimatzky’s (a commercial bookstore chain in Israel). Unfortunately, I lost it during an apartment move. But of course, there are a lot of photography books that I love. Evidence by Larry Sultan, and Tulsa by Larry Clark. These are bodies of work that are best experienced in a book, the minimalism, the close looking, and the possibility for lingering.

Making books is like…

It’s like making movies, or at least very close to it.

What book should we add next to our library?

Itai Eisenstein, BACKVIEW, and Yigal Shem Tov, Albums 79-80.

Where can readers buy the book?

Hamigdalor book store and the Ashdod Museum of Art.

Anna Yam, born in 1980 in Yekaterinburg, USSR (now Russia), lives and works in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. She has a BFA from Hamidrasha Faculty of Arts, Beit Berl College, and an MFA from Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem. In her works, Yam takes and also appropriates photographs of others, through which she contends with sites related to her personal and family biography and travels to foreign places. In 2019, she presented a solo exhibition at the Ashdod Museum.

"It started from photographs I would take while visiting family. I would look and steal a photograph, scan it, return it, or forget to return it. Many were angry with me that an empty pocket was left in some album."

"My parents were younger. They opened the windows, there are no more heavy carpets or drapes hanging from the ceiling. Most immigrant houses looked as if they hired the same interior decorator. Clean counters, everything in beige, integrated kitchen. There is excitement from the “new". In Olympus, there are a lot of skyscrapers. It’s a naïveté that arouses some discomfort."