Before we dive into the conversation about the book and the performance that accompanies it, let’s start with a kind of introduction of each of you. Johanna, you are a curator who works in Berlin. Ana, you are an artist who works in Tel Aviv. Can you tell us about your professional relationship, and how the book came about?

[Johanna Markert]: We met at a residency program in Stuttgart called “Akademie Schloss Solitude,” where we got to know each other and started visiting other artists’ studios together and talking with each other about our work. The first project we created together was an exhibition I curated together with the collective I am part of—Anorak, following which we invited Ana to participate and create new work. The dialogue continued from there and we remained in touch.

[Ana Wild]: We also published a conversation in the residency’s online magazine; they called that conversation: "Need proof? Poof!”

I will start with the first question that came to me regarding the project. Your choice to not only read Simone Weil’s book as a performance work, but to create another book with the same title—Gravity and Grace, is interesting. For me, as a researcher of Weil, the philosopher, it’s like reading the Bible and have someone give another book the same title, “The Bible.” Can you tell us about the connection to Weil, and then about choosing the name for the work?

Johanna: That’s an interesting question. I had been reading Simone Weil over the last few years. I chanced upon her in a book by the poet Anne Carson called Decreation. I was very attracted to Weil’s voice, I became obsessed with her writing, especially Gravity and Grace. Her fragmentary writing is concrete and hard to grasp at the same time. I started discussing the idea of self-effacement with Ana, and we came to the conclusion that her writing could be better understood through reading, which is an action. Regarding the title, Ana, would you like to say something?

Ana: Part of my interest is dealing with the question of how to work with ideas, and how they become tangible. Their plasticity, their form of exchange, which is not necessarily intellectual. How can we take concepts that we read, that we have become attached to, and transfer them to an experiential space. Not only to discuss or talk about them, but also to create a situation in which they can be shared in a different way. To let people experience our understanding of what “self-effacement” is, what grace is, what gravity is. Regarding the title, first and foremost it is a beautiful, accurate and poignant title, which we thought would be a shame not to use. It accurately captures the dichotomy between these two forces that are experienced and at the same time, are unperceivable, mystical.

Something happens in the coupling of these two concepts; one coming from a bodily experience and the other from an inner, religiously contextual experience—creating a third space. Originally, it was a temporary title, and in the end, it stayed with us. It positioned our work and the book in relation to Weil, without necessarily claiming anything about the nature of our relationship to her ideas. You could say we borrowed or appropriated the title as a tactic to create a relationship.

“Gravity” and “grace” are two words with philosophical and mystical meanings. If we continue with Weil, and if possible, with a separate thought about the performance, they are very much related to the body. I wondered about the connection between gravity and grace, and the practices of each in terms of thinking about the body; Ana, as a performance artist, and Johanna, as a curator, thinking about the exhibition—what is the connection between gravity and grace to your work?

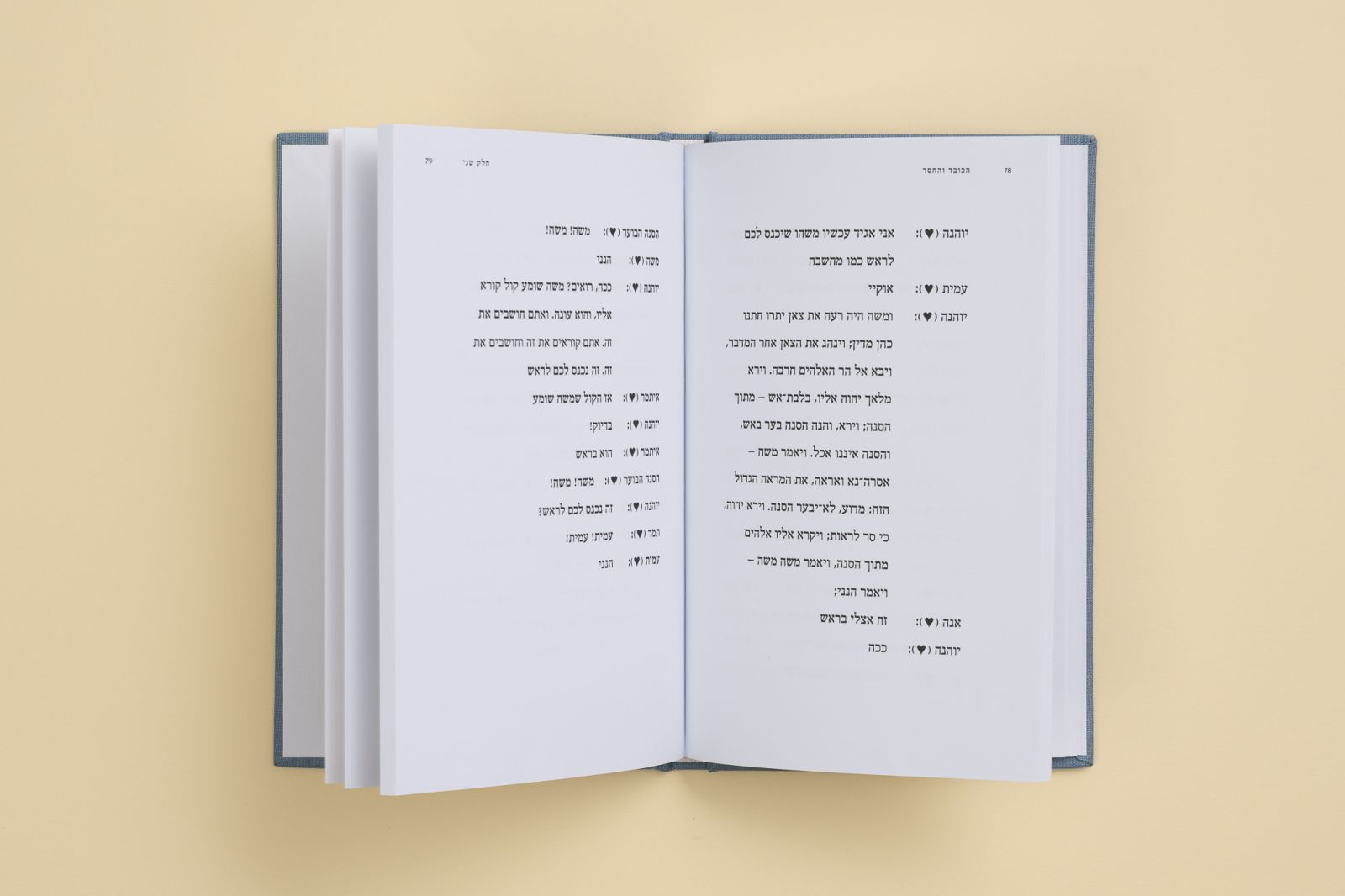

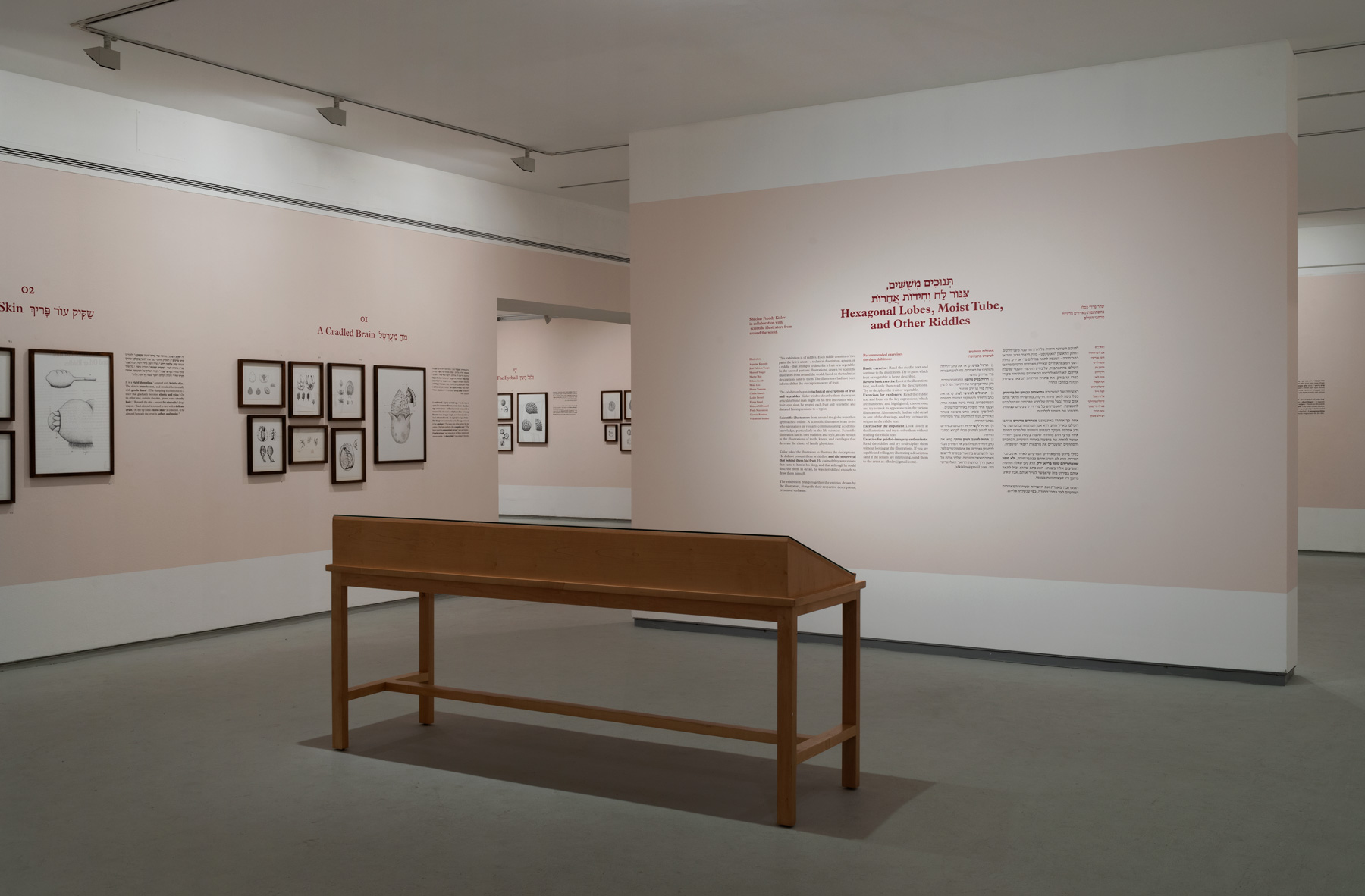

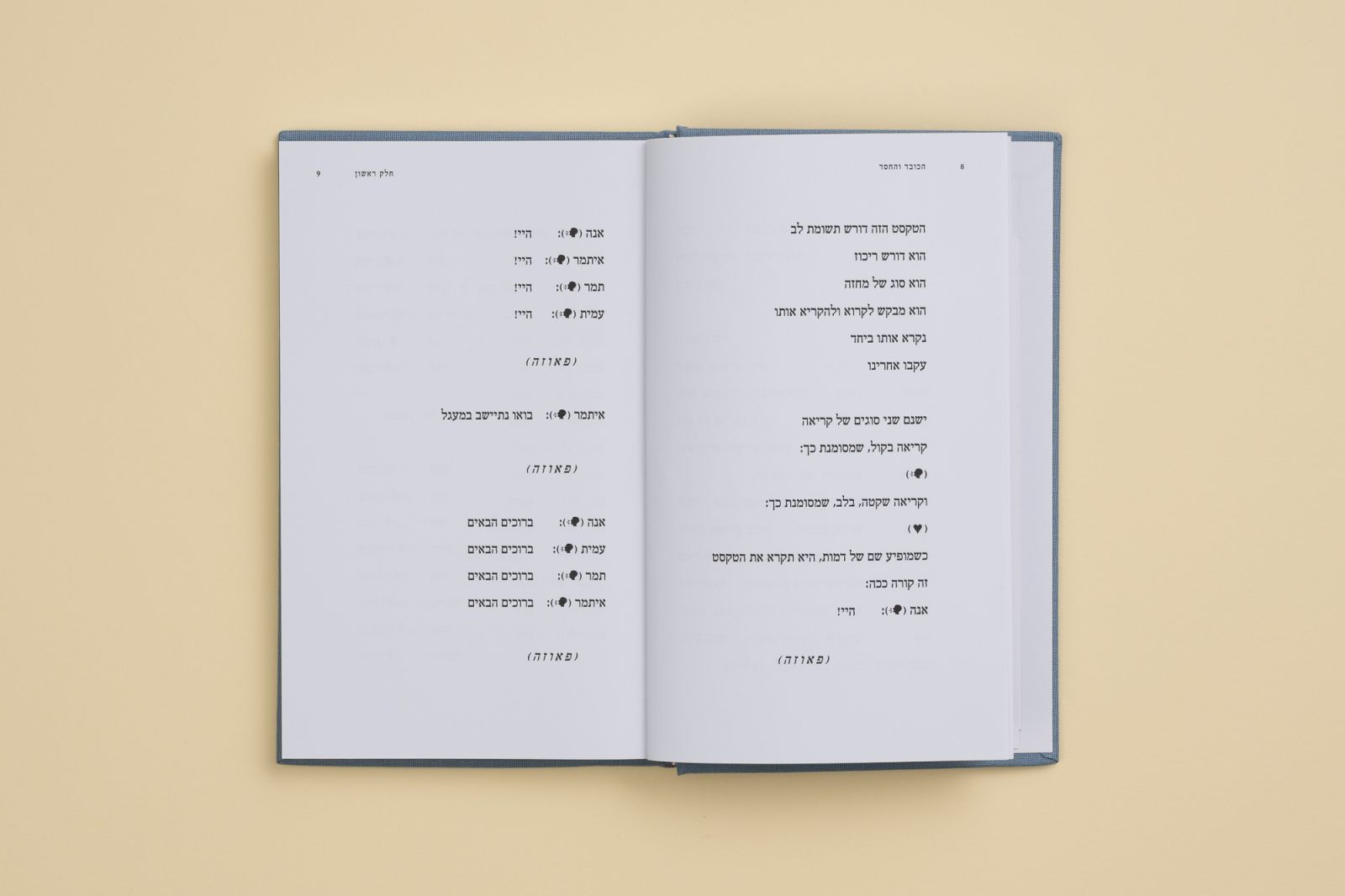

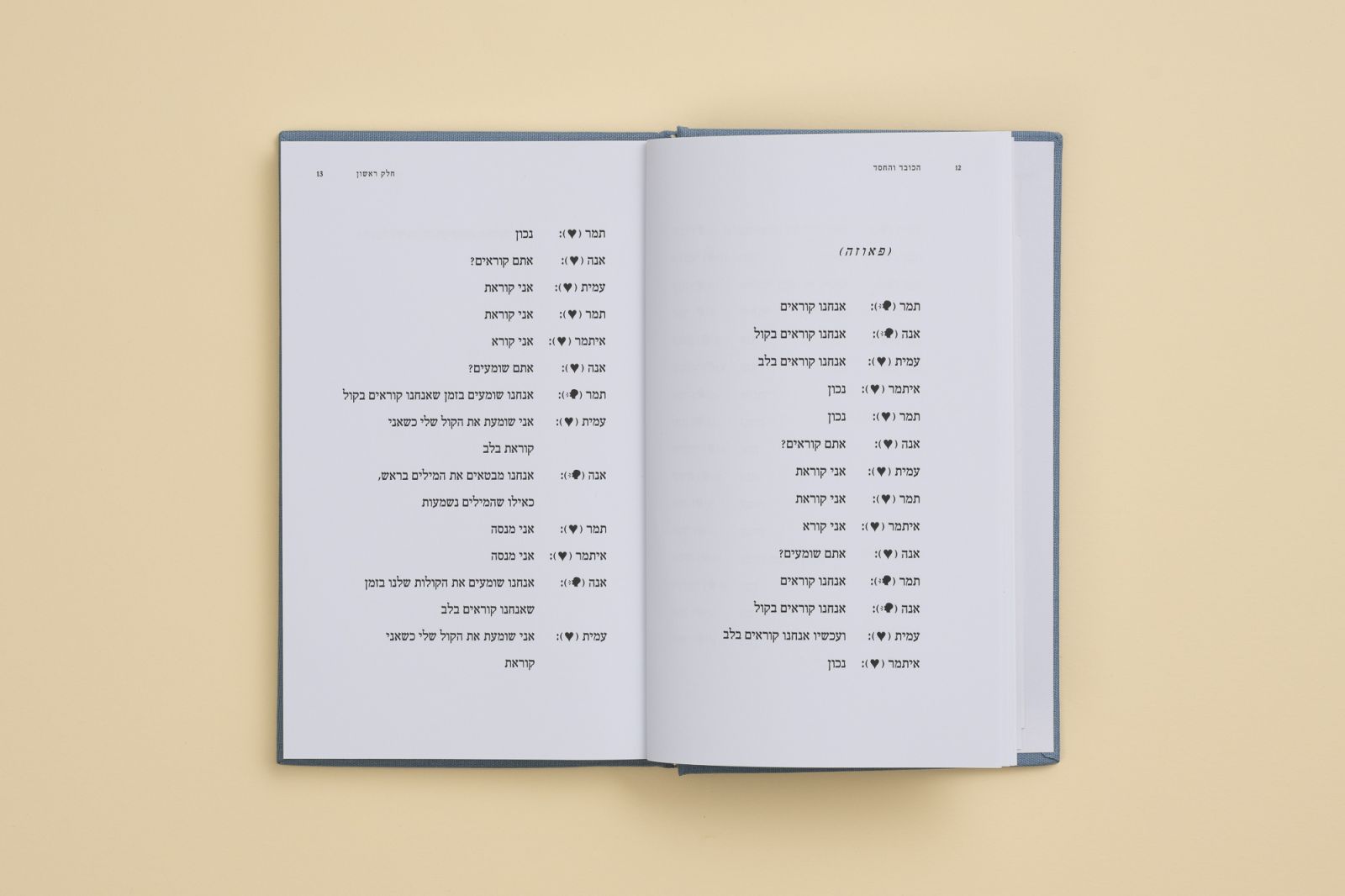

Johanna: First, with respect to the work—it deals with the paradox of the voice. We were both drawn to the idea of trying to capture the voice without the body, when reading or speaking. In the book, which is built in the form of a play, there are the entities, of the performance and of the audience, sitting in a circle and reading together. That is, they appear together. There are sections that are read aloud and sections that are read quietly, to oneself. It’s a give and take between voice and its movement among different bodies through reading or thinking, and this was something we wanted to be able to balance: an interplay between voice and non-voice throughout the play and the performance.

[Ana]: We worked with the idea of “gravity” and “grace” as equivalent terms for body and voice. It’s not something we were a hundred percent faithful to, but it helped us. The idea of the body and the voice as two parallel entities is related in my work to the concepts of “self” and “identity,” of abilities to act in the world. For Weil, “gravity” is a long list of things that relate to the limitations of human ability. In our process there is a distinction between how things appear (the gravity), and how they sound (the grace). The idea is of revelation, exposure, wonder, awe—that is, a perceptual space that is beyond the physicality of the body. It’s not that the body isn’t capable of mystical experiences, we know that it is, but in Gravity and Grace I was interested in tracing the ability of the voice to be an agent that is not associated with the body, a free agent that can travel distances in ways that the body cannot. This is the point where the voice is a gateway to imagination, to a space where miracles can happen, beyond the limits of experience.

The book touches on this very delicately; for example, in the second part of the book there is a quote with several names: the moment when God reveals himself to Moses in the burning bush. In the biblical story, God gives Moses a task, to liberate the Israelites from Egypt, and in order for them to trust him, that is, for them to believe that he carries the word of God, he receives signs to present to them. In other words, in order for them to believe that he is conveying the word of God, he has to show them physical evidence. And for me, that’s the gravity. The need for evidence, for some concrete testimony to the miracle.

The question I ask the audience is: Why are things that we can see with our eyes or experience physically, necessarily stronger or easier to classify as a “miracle”? In our book, it is written: “Amit picks up a stone and drops it, and the stone turns into a snake.” We read it, we said it, we could imagine it. So why is it less of a miracle? In my eyes, this is grace. You can look at a stone and say, “Oh, it didn’t turn into a snake.” It obeyed the laws, the physical order that we are used to accepting as real. If nothing “magical” happened,” does it mean there is no magic? Does it mean that, “God is not with us”? These, I would say, are the limits of “gravity.”

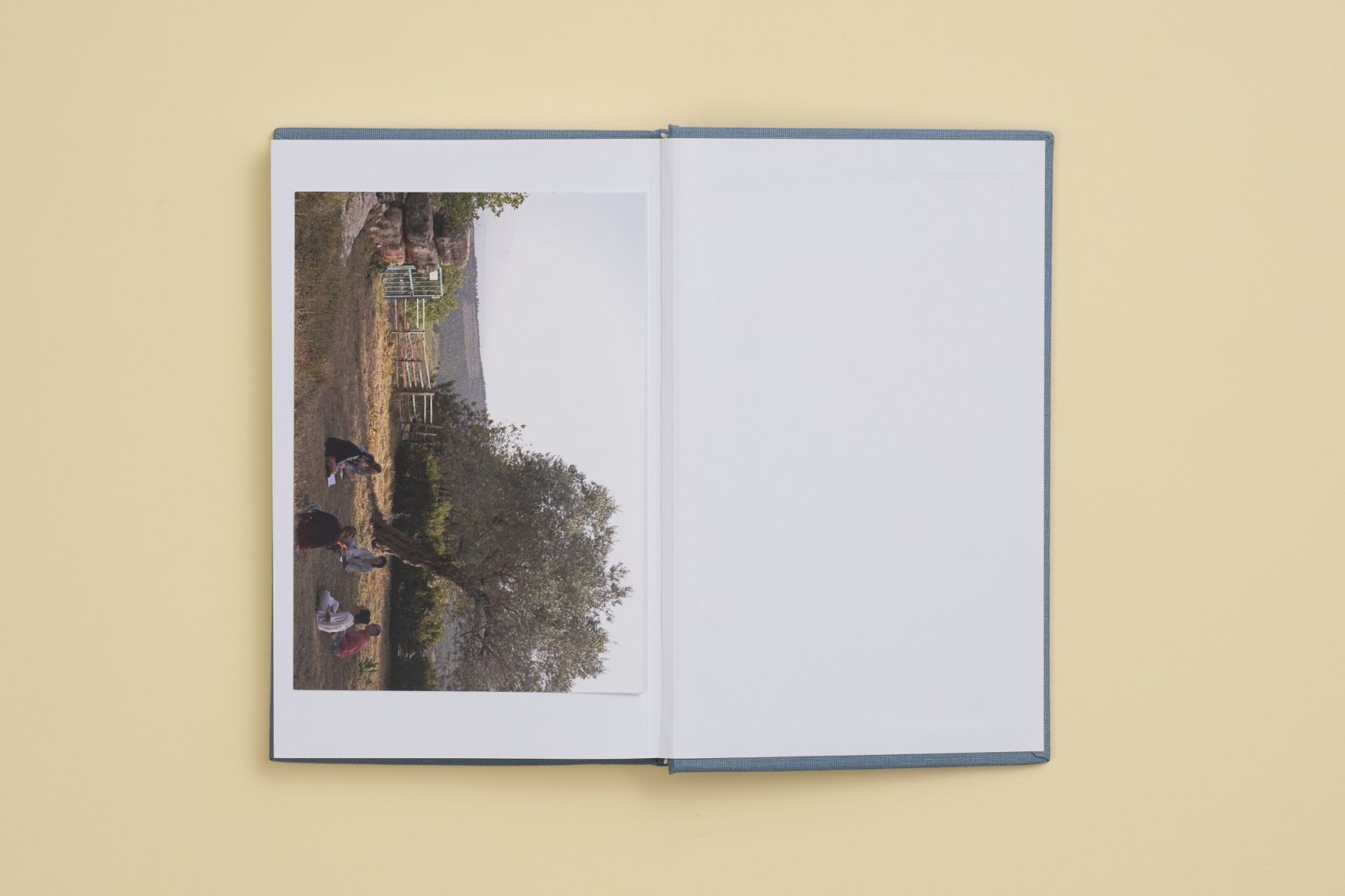

Johanna: From a curatorial perspective, the thought process dealt with how the audience would enter the work, which was commissioned and performed for the first time at the 2021 Diver Festival. There were moments throughout the work when a physical meeting with the audience was not possible due to the coronavirus, and this pushed us even more to think about modes of encounter.

Three names appear in the book in addition to yours, Ana: Amit, Tamar, and Itamar. You both chose to keep the performers’ names, even though the book is its own separate entity and is sold on its own. In addition to first names, you also used mythological names, and also the names of elements, fire, sun, earth and the forces of nature. Is there a common denominator through which the audience knows the names? Could you say something about this choice? I’m not sure you refer to them as “characters,” so is this the “role” of “Amit”? Does the name itself have meaning or the particular person whose name it is?

Johanna: It’s a book and a play, which has characters with different names, some of which are first names. When I see it in print, and I read the text as a play, I accept the fact that these are the names of the characters. There is Simone Weil, Ana, Johanna, Itamar, Tamar... at the same time, the text lets the characters speak and creates them. The characters do not necessarily have to be related to real beings. This relates with what Ana said earlier about imagination, and the voice crossing the boundaries of the physical body. This happens in every book. The author wrote it so that there will be a separate thing in the world that bears his voice, which is not physically present, but it does not make the words any less meaningful for us. Once the work enters the textual realm, the characters have a life of their own.

Ana: I’m interested in how people understand things. In a minor way, somehow, some people will come to experience the performance and recognize that Tamar is Tamar, and Itamar is Itamar, and they will know that maybe at some later point in time someone else will “appear” in this role, and it is not certain that her name will be “Tamar.” That if they take the book home and read it, then there will no longer be any certainty that “Tamar” is “Tamar.” It says in the festival program that it is performed by Tamar Even-Chen, Itamar Banai, Amit Tina, etc. It’s a connection that not everyone will necessarily make, but it’s the information that’s there at that moment. Moreover, we worked for almost six months, and wrote for the people who were part of the process we undertook at the Diver Festival. We were a group of six people and were engaged in “being a group.” We worked with this thought in different ways throughout the year. In parallel, Johanna and I met to write and slowly develop the text. We really wrote with the thinking of what the people in the group would sound like.

Theater contains the tension between the actor and the character on stage—what is referred to in theater jargon as the suspension of disbelief. I know that Leonardo DiCaprio is now “Romeo” and I play along with that. At the same time, I know he is Leonardo that is Romeo. But what happens when I read the text of Romeo and Juliet? I imagine “Romeo” as one entity, not necessarily split between “character” and actor. You can also say that when I read, I myself become the character that reads Romeo’s words, and through them, I experience Romeo’s actions as an “entity” in the world. In the performance, this gap is in doubt from the start, whether or not there is this suspension of disbelief, we allow ourselves to be rid of it, to assume that it is not important. In the performance we created, I am also Ana the author of the book, also a random performer who performs the text in the play, also a character in it, also part of the audience that listens to the voices, the speakers and the silent ones.

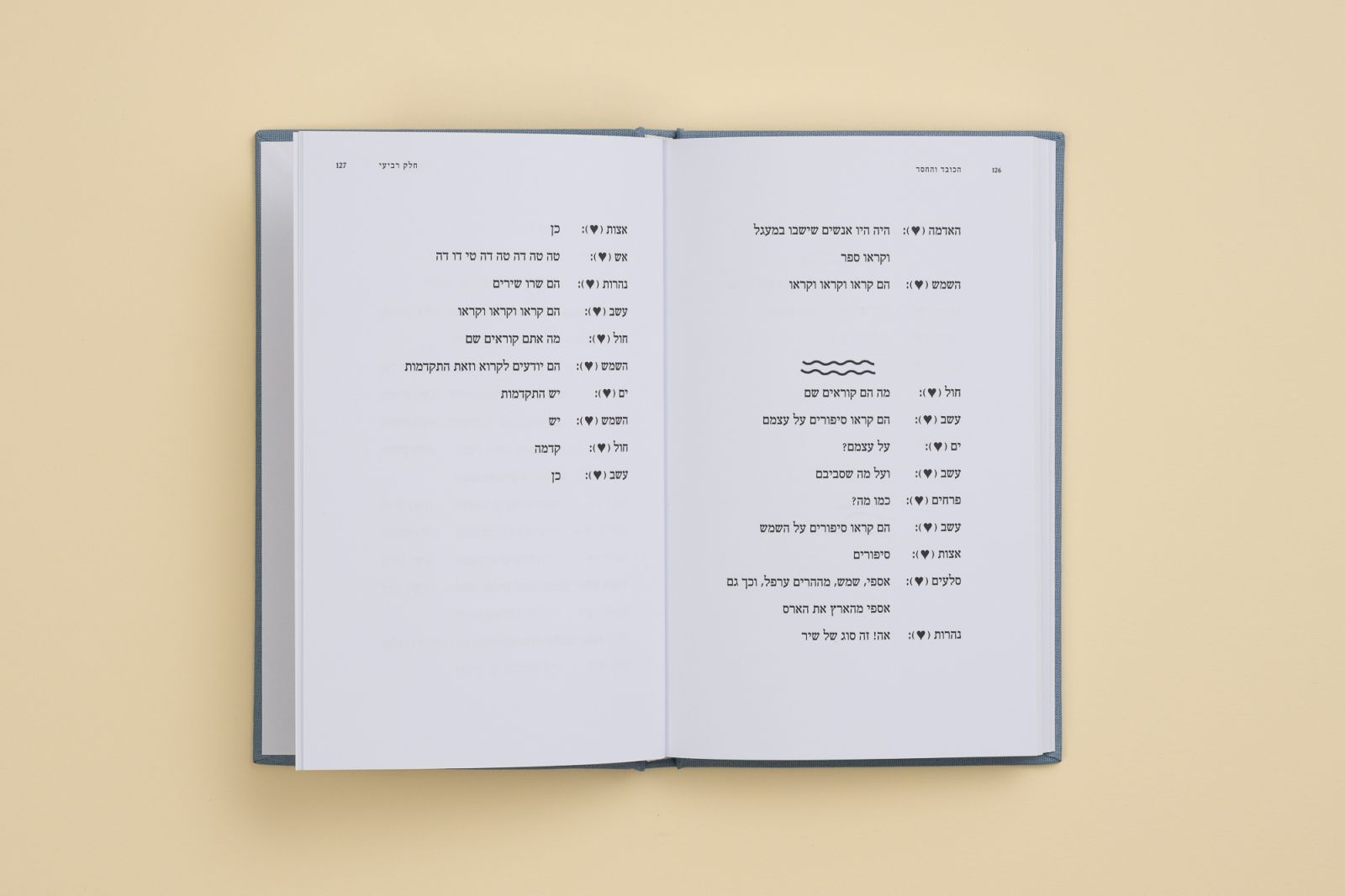

Continuing this line of thought, the question of the first name raises the question of the singular, the particular, and the connection between it and the social space. Despite the first names and the distinction between the characters and the actors, it seems to me that the work is also very much connected to “being together” or about “togetherness.” For example, when the speakers say, “We are like a choir” or they shout, “Right, right, right” on page 64. It seems that despite the separateness, the work is very connected to the characters being together. Also in the “instructions” at the beginning of the book, you write, “to be read together.” I wonder if you would like to say something about this “togetherness.”

Ana: Thanks for bringing that up, it’s an important aspect of the work. One of the first things we wanted to achieve was through the question: “How can a group of people be together, outside, quietly?” We talked about the choir as a way to place the solitary speech, the monologue, opposite the group. This is a key that is always found in my works: How do we understand something together. For me, this tension is always found in art: “I understood something, but I didn’t understand it alone.” We are in constant dialogue with the world.

Johanna: From the beginning, we wanted to create a community, or a choir of inner voices. For me, this is an important curatorial question: how to bring people together, how to make an experience a shared one. Reading together is something I haven’t really done before, although this theme is in all my projects as well.

This actually brings me right to my next question, which has to do with reading. Weil’s writing includes the term “reading,” to which she dedicated an essay—“Essay on the Notion of Reading”—in 1944. She claims a similarity between reading and feeling, between the thinking and the feeling body, but these are not completely distinguished in her thought.

She compares two mothers who receive letters informing them that their sons have died. Only one of the mothers is literate. That is, both mothers sense the black spots on the paper, but only one can “understand” them. The one that can read can feel a pain that goes beyond what she can see, a pain that the other will not feel. Thus, Weil claims a difference in the way the “external” world affects the mind, but not the body. The pain is not present in the letter itself, but in the meaning resulting therefrom, which leads Weil to emphasize how our lives change through the implications we read into every phenomenon.

In the same line of thought, in Gravity and Grace she says, “each person cries out in silence to be called differently.” I read this quote as a call, a sort of categorical imperative, both to read and to be read, “differently.” For Weil, one should read endlessly, others and what’s known as reality, and to never let anything appear to us in a singular and defined way. In my opinion, she calls for a never-ending reading, and this raises the tension between the visible and the invisible, which inevitably exists in performance art. This comes out amazingly in this work, especially in the moments when the actors are reading or looking at the book. The audience has no grip on these moments. In this sense, performance is almost the only medium in which such an act can be presented. It made me think of Beckett, of Waiting for Godot. If with him they wait, with you they read.

Johanna: What you say about the visible and the invisible is very beautiful. It reminds me of another, very sad quote that appears at the end of Gravity and Grace: “To see a landscape as it is, when I am gone.” What is it like to be in the world without being present in it? A desire for the body not to be present so as not to interfere with what is being felt, on the one hand, but one also needs the body in order to feel. At the same time, it also describes a state of great attention, which is connected to being in a passive state, and this is another important term for Weil, which we wanted to get closer to.

To produce sensitivity, listening and awareness that we are doing it together. The very fact that we use the same words, almost like thoughts in someone else’s head. A feeling of connectedness, to humans, but also to everything around us; the voices, the earth, the sun, the forces of nature. We are in a situation in which the self retreats in order to open up. If I go back to the quote, to experience a sadness that almost approaches death. Weil says: “When I’m in a place, I disturb the silence of the sky and the earth, with the sound of my breathing and the beating of my heart.” Along with the awareness of the limits of human life, arises the awareness of things that are beyond human consciousness.

I get the impression from what you are saying, without being superficial, is that everything is a performance, and reading—maybe you don’t want it to be distinct. As you put it differently before, every time I read a book, a person is missing. Does this resonate for you reading Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace?

Johanna: It is very much related, and somewhat similar to the names, which are real but contain the possibility of change. We could perhaps say that Weil’s book, the book-play and the performance are connected on a sequence of time and the experience of those who will take part in each of them. I hope this works for people.

I have a feeling this will happen. Ana, do you want to add to that?

Ana: Yes. I feel that being a performance artist does not necessarily mean being an artist who creates a performance, but rather having a sensitivity towards the performativity of things in the world. This is expressed, for example, in the desire to be both—and and not just either/or. It has to do with something I call expanding the boundaries of choice. In making art, there are many choices: you choose the color you will use, the dimensions of the work, the rhythm. These are choices made in relation to the work itself. To expand the limits of choice is to make choices also in relation to the conditions in which the work will be seen, experienced, read. The third expansion is to understand that these choices are in the “world,” in relation to the world. To understand that art is an experience in the world. I feel it is this sensitivity that led us to Simone Weil. It is not just about recognizing a phenomenon in the world, but recognizing that each of our specific poetic and mystical perceptions participates in the way the world manifests itself.

This relates to an important question. The question of God that arises in the book-play. The question of faith for Weil is related to the ethics of self-effacement, where there is nothing, where there is absence. For example, you write: “There is always a voice that says something,” but then, nothing is said out loud. Silence rises once more, but along with it, faith. Ana, In a preliminary conversation, you told me that the feeling of leafing through the book is important to you. It made me feel that within the act of leafing lies faith—that something will come. I don’t know what, but something will come. When I imagined myself reading the book, and thought of it as a performance, I wondered what your thoughts on faith are.

Ana: I like that you say that there is faith in the act of leafing, yes, when you read you have to believe that something will come when you turn the page. Faith involves agreeing to make room for what is beyond your comprehension, to trust it. Personally, I think that I always wanted to be able to believe—in God let’s say, and I was too cynical. I grew up secular, and despite that, I had faith. I believe that the creation of art has an effect, and I believe in miracles. For me, reading the story of the stone falling and turning into a snake is no less miraculous than watching a stone turn into a snake. When you believe in something, you feel it is “real,” or you can even say —you know it is true. That’s the way I feel about leafing, you have to believe that there is something real in it; and then, if you agree to believe, even if the pages are blank, we have already entered into an agreement, something real exists in them.

Further to that, the actors sing “Ring of Fire,” which brings up the question of love. So, love and faith are intertwined for Weil, which is the reason for the follow-up question. I wondered about the place of love in the work.

Johanna: For Weil, God is an absolute being but absent at the same time, and love is a paradox of union and self-effacement. Love has transgressive potential, that’s why the “Ring of Fire” is there, because of passion.

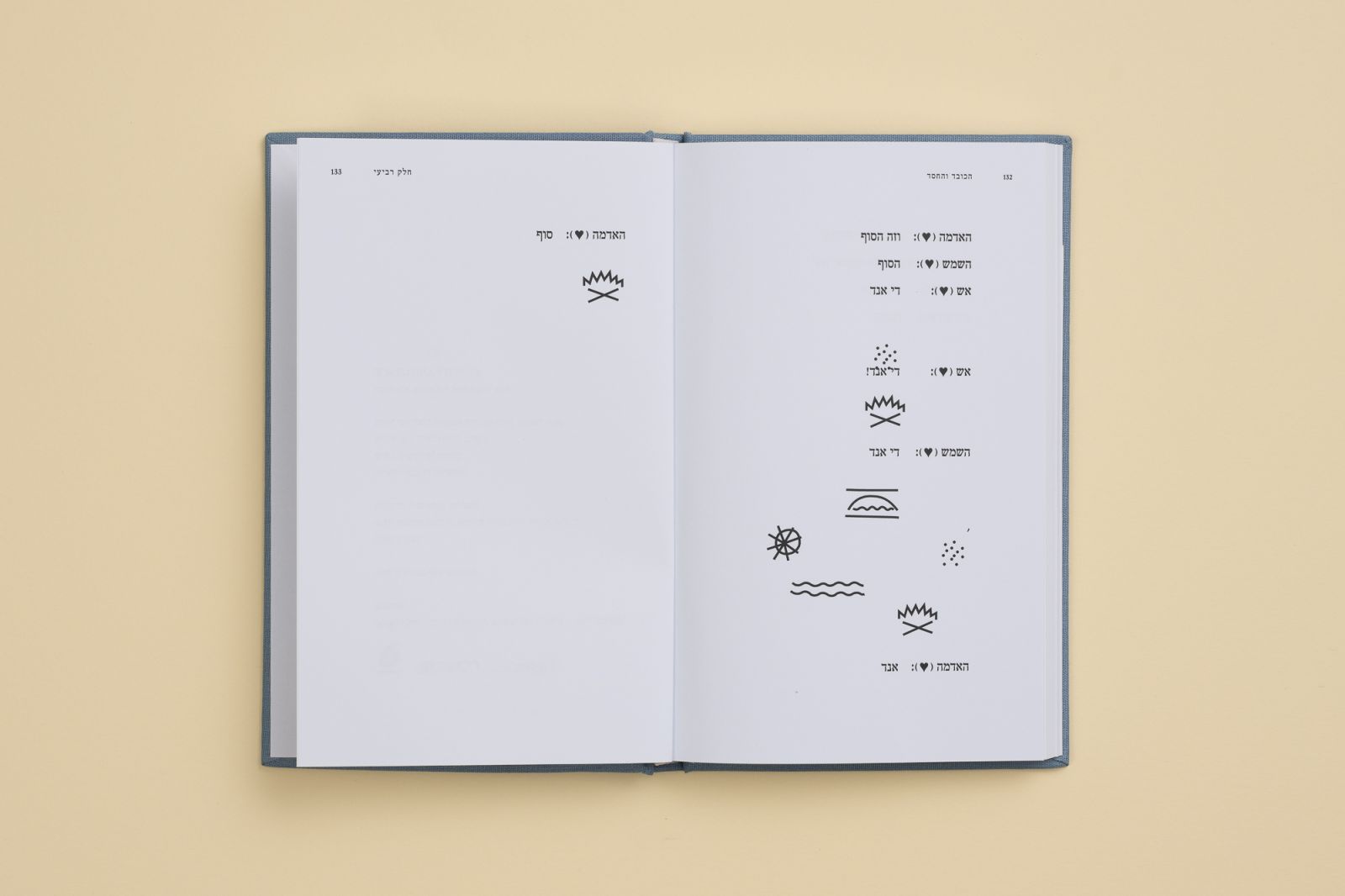

Yes, you have to destroy a part of the “self” in order to love. This brings me to Otherness, and in particular to the “speaking nature.” You placed the performance outside, next to trees, and added characters called “forces of nature.” Is that connected to distancing from the gallery, to isolation and social distancing? And what does it mean that nature speaks in a human language? Towards the end of the work, it receives a new, graphic language, which looks like a hybrid between hieroglyphs and old digital fonts. I’m trying to imagine how you show these shapes in the performance.

Ana: The premise of nature speaking in the work is connected to the idea that we present very naively, when we say “if you would shut up for a second, maybe you will hear things.” Like Pocahontas’s song in the Disney movie, if we just listen then we’ll hear the wind and the stones. Most of the time, we don’t listen to nature or to one another or to God. Language can be a means of generating thought, or a way of describing nature, or a way of defining protocols of religious practices. Language, being the most magical force, for me, offers us things that are beyond the human “I.”

Johanna: The letters printed in the book carry meaning in their own right, and they also comprise words. But the meaning is created through the actual experience of working together. The symbols point to the fact that all of language is a convention, and has meaning within a socio-cultural context.

Yes, and there is also the saturated layer of symbols. Could you say something about the design? Was it you who drew the letters, or the designer?

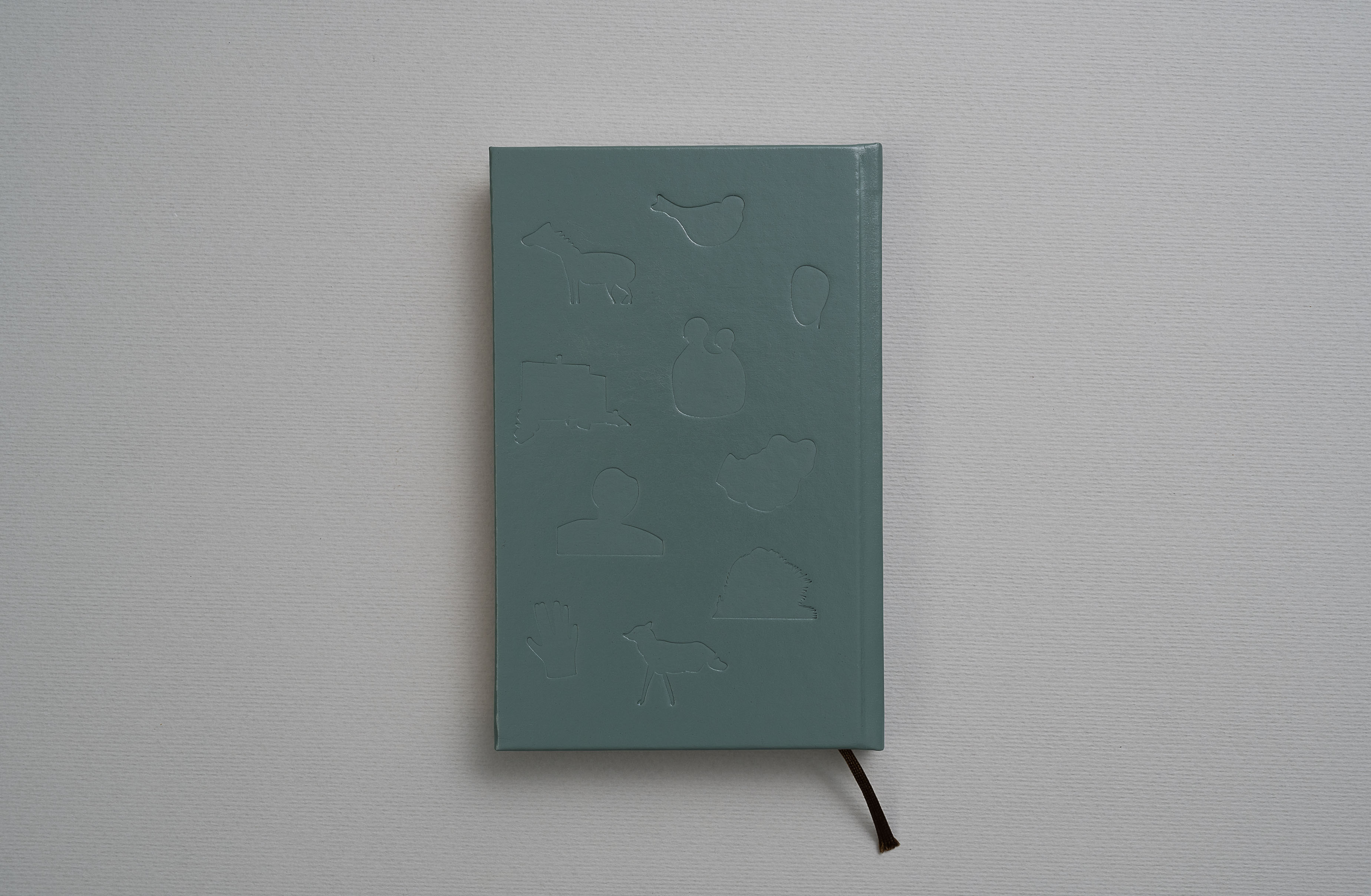

Ana: I drew them after studying the lexicons of symbols from different cultures, from which I chose specific examples that I liked. I wanted to establish the movement of words from pictograms to writing in letters, a transition that took place in so many cultures in different periods of human existence. I wanted to connect with these archetypes as well as take a step back from language, as we know it now. Language is a very mysterious, mystical thing. The printed book has a hard cover, and there are no letters on it. It was a very clear choice for us. Speaking of what you said earlier about “the Bible,” we wanted to keep it a mystery, that it would be a “book” and not “the book of gravity and grace.”

So you’ll perform with the work at the Artport Book Fair (March 2–5, 2022). Johanna, will you be there?

Johanna: Yes. This is the first time that I’ll see the work, I’m very excited.

What book should we add next to our library?

Ana: Power Play by Sonia Kazovsky, an Israeli friend who works in the Netherlands. It is a book that can be placed next to our book on the same shelf. It also asks, “Am I a book?” It’s a book that is an invitation to an action, to dramatization, to performance.

Johanna: A Grin Without a Cat: The Very Tale by Katharina Jabs. It’s a cinematic novel with an epilogue based on a movie with the same title. A rich and complicated book with materials about the process of making the film.

Where can we get a copy of the book?

On the website of Poraz et Navok, Artport Book Fair, Magasin III Jaffa Books, Lighthouse bookstore, Sipur Pashut, and Uganda in Tel Aviv, Adraba in Jerusalem and Milta in Rehovot.

Ana Wild, born in 1987, lives and creates in Tel Aviv-Yafo. She is a graduate of the School of Visual Theater in Jerusalem and received an MFA from DasArts in Amsterdam. A performance and installation artist, Wild is interested in voice, in speaking, in words, in knowledge-structures, in anthropology, history, mythology, poetry, graphic design, electricity, in creation ex-nihilo, in miracles, in musicality, learning, understanding, repetition, cyclicality, in Hebrew, English, French, Arabic, in translation, in print, in magic, in adventure, in friendship, in agency and in power. Her works range from gallery to theater, from live performance to installations and video. She teaches at “Olympus,” a program for creators at Liebling House, and the School of Visual Theater. Her book Gravity and Grace was written in collaboration with Johanna Markert, an artist and curator who works in Berlin. The two met when they participated in the “Akademie Schloss Solitude” residency program in Stuttgart.

"We worked with the idea of “gravity” and “grace” as equivalent terms for body and voice. It’s not something we were a hundred percent loyal to, but it helped us. The idea of the body and the voice as two parallel entities is related in my work to the concepts of “self” and “identity,” of abilities to act in the world."

"One of the first things we wanted to achieve was through the question: “How can a group of people be together, outside, quietly?” We talked about the choir as a way to place the solitary speech, the monologue, opposite the group. This is a key that is always found in my works: How do we understand something together. For me, this tension is always found in art: I understood something, but I didn’t understand it alone."