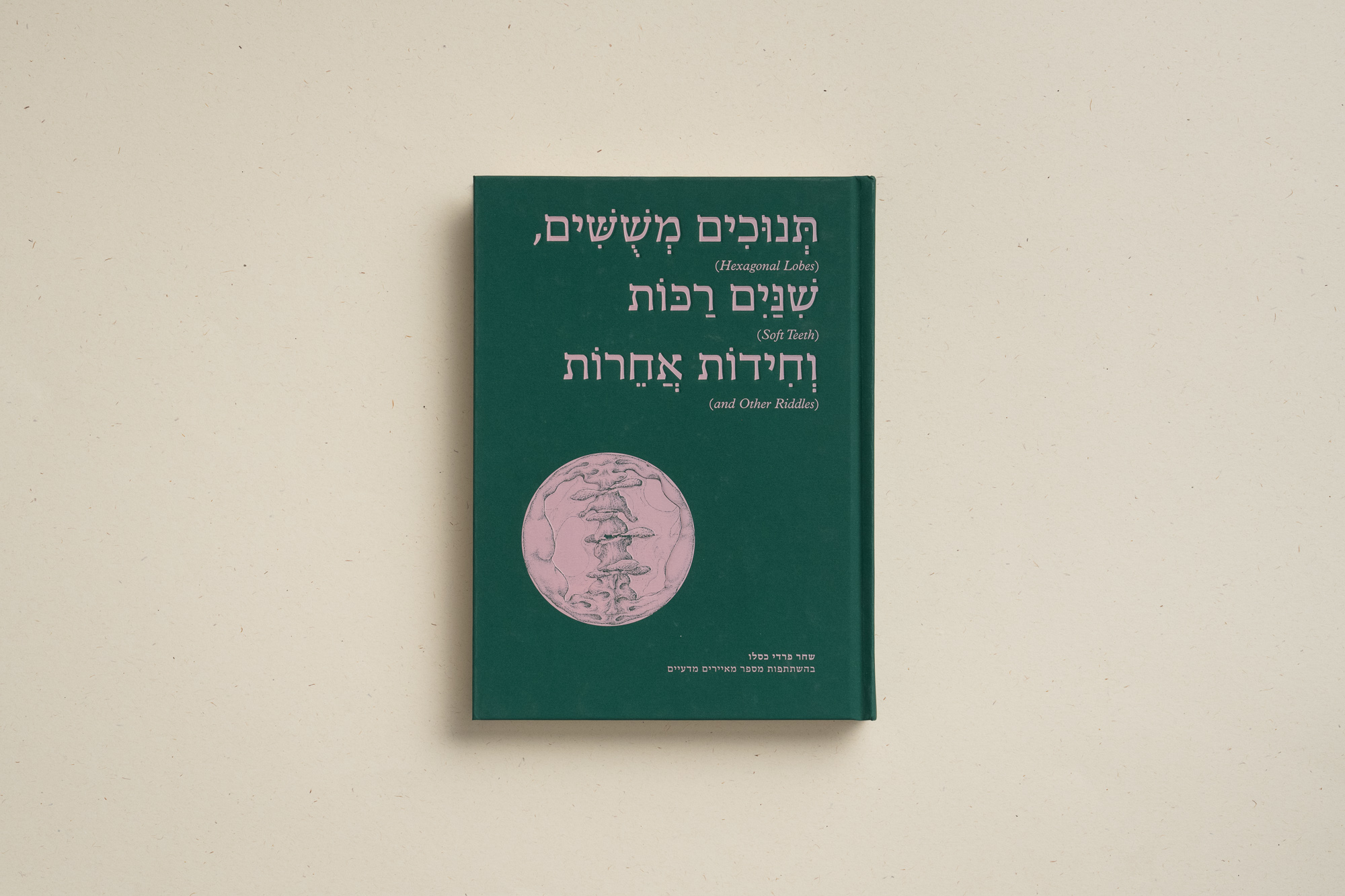

Since this book is one big riddle: let’s say you were to send a description of it to unsuspecting scientific illustrators, what would you write?

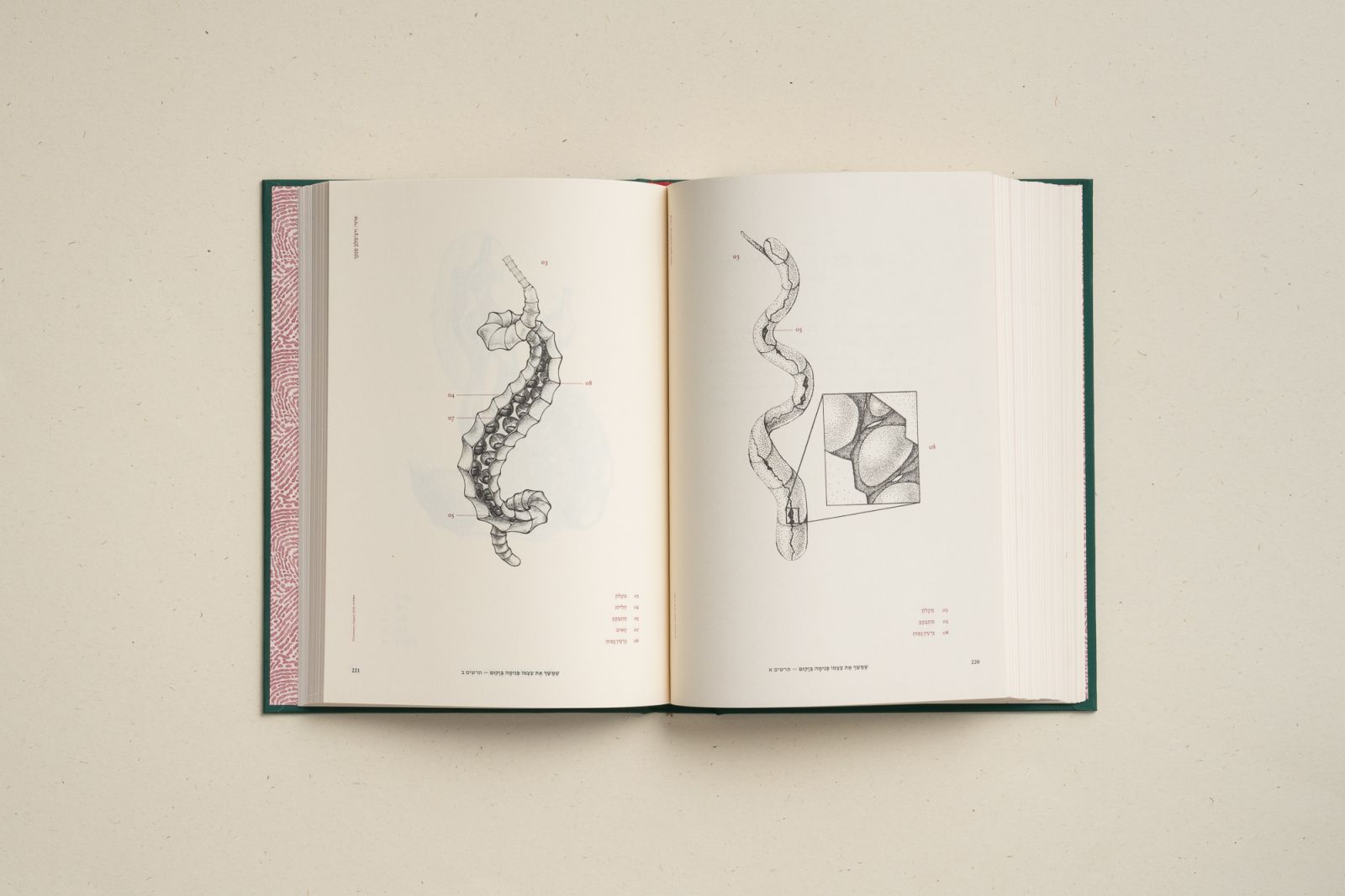

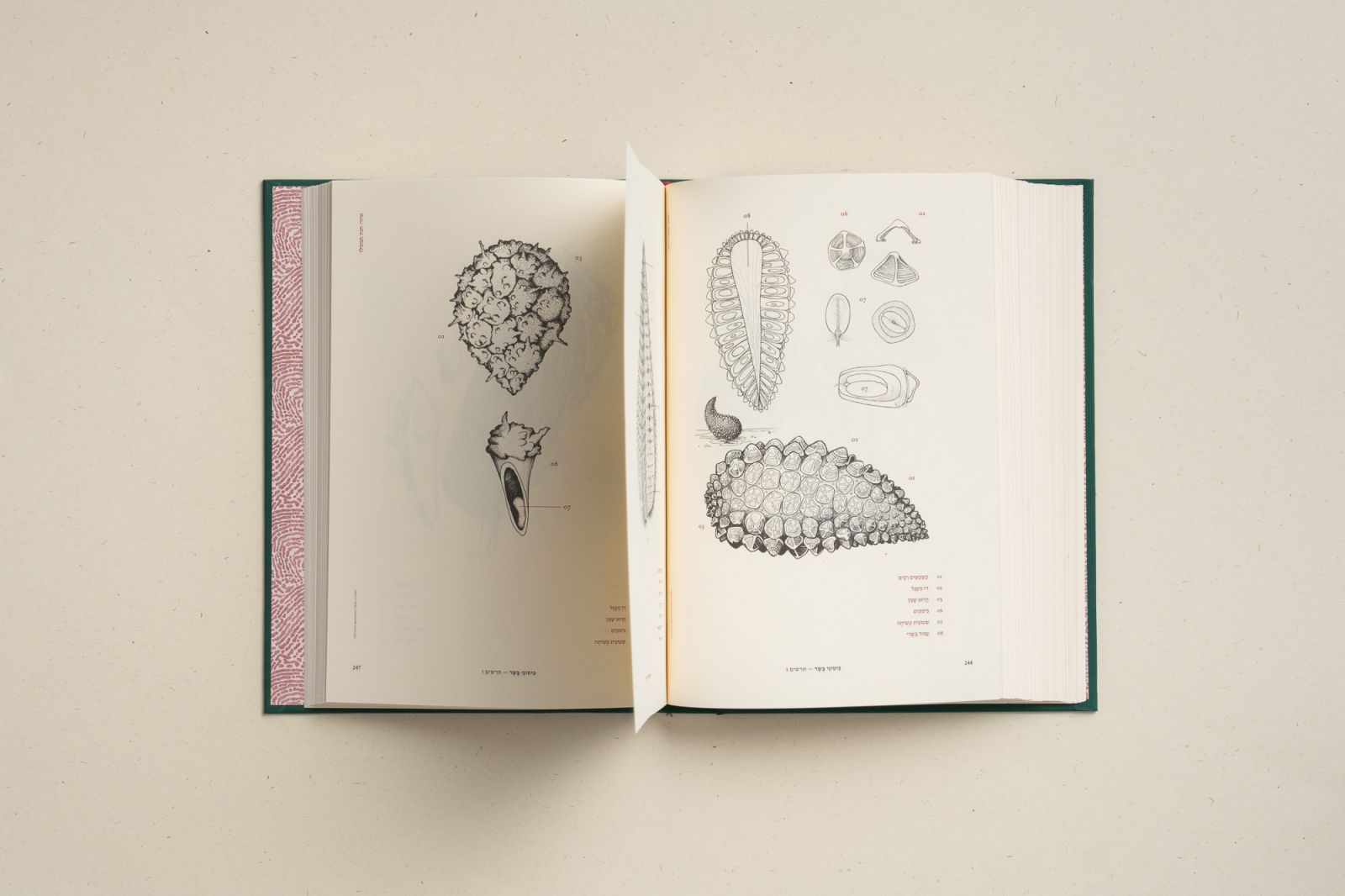

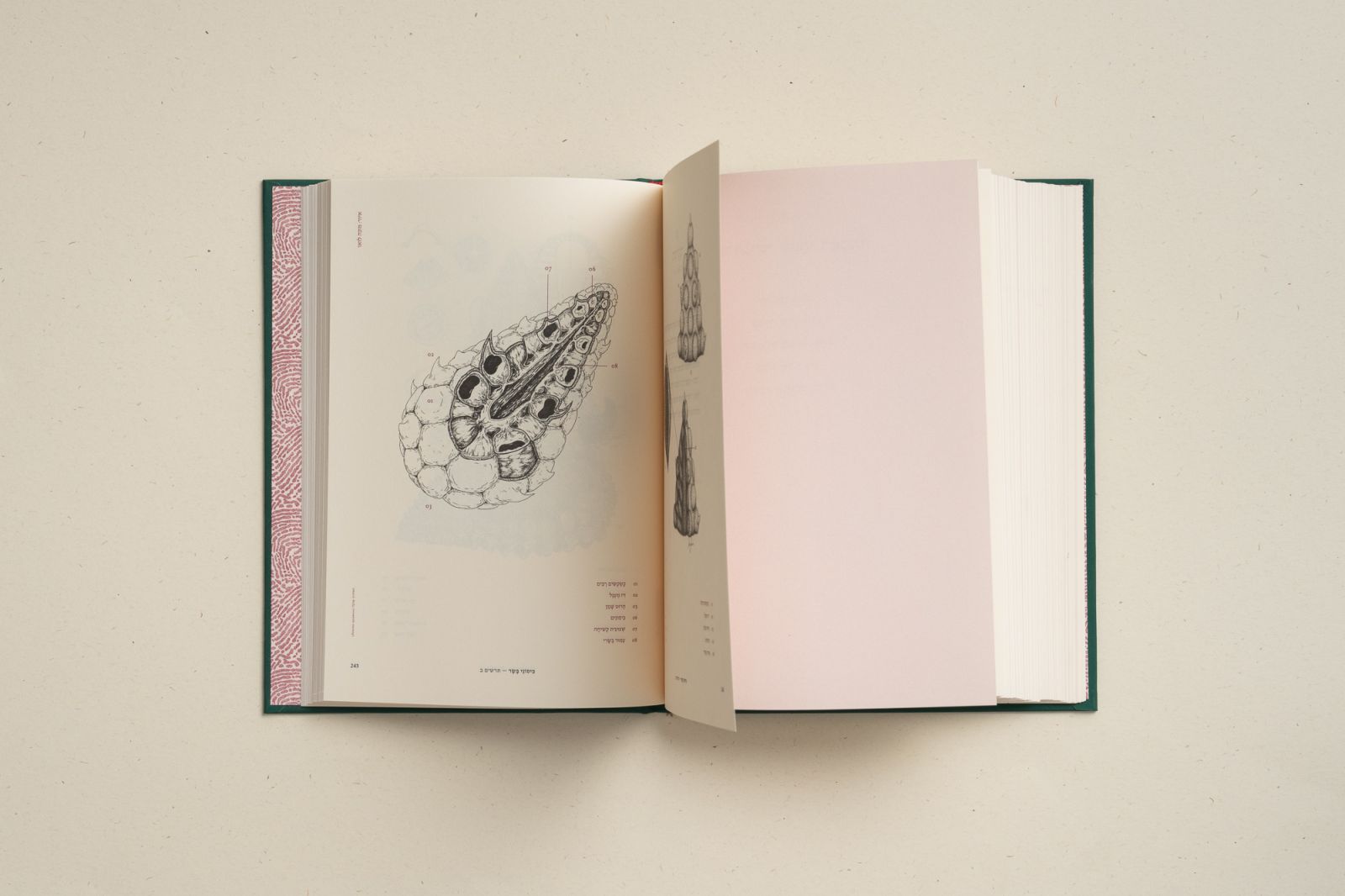

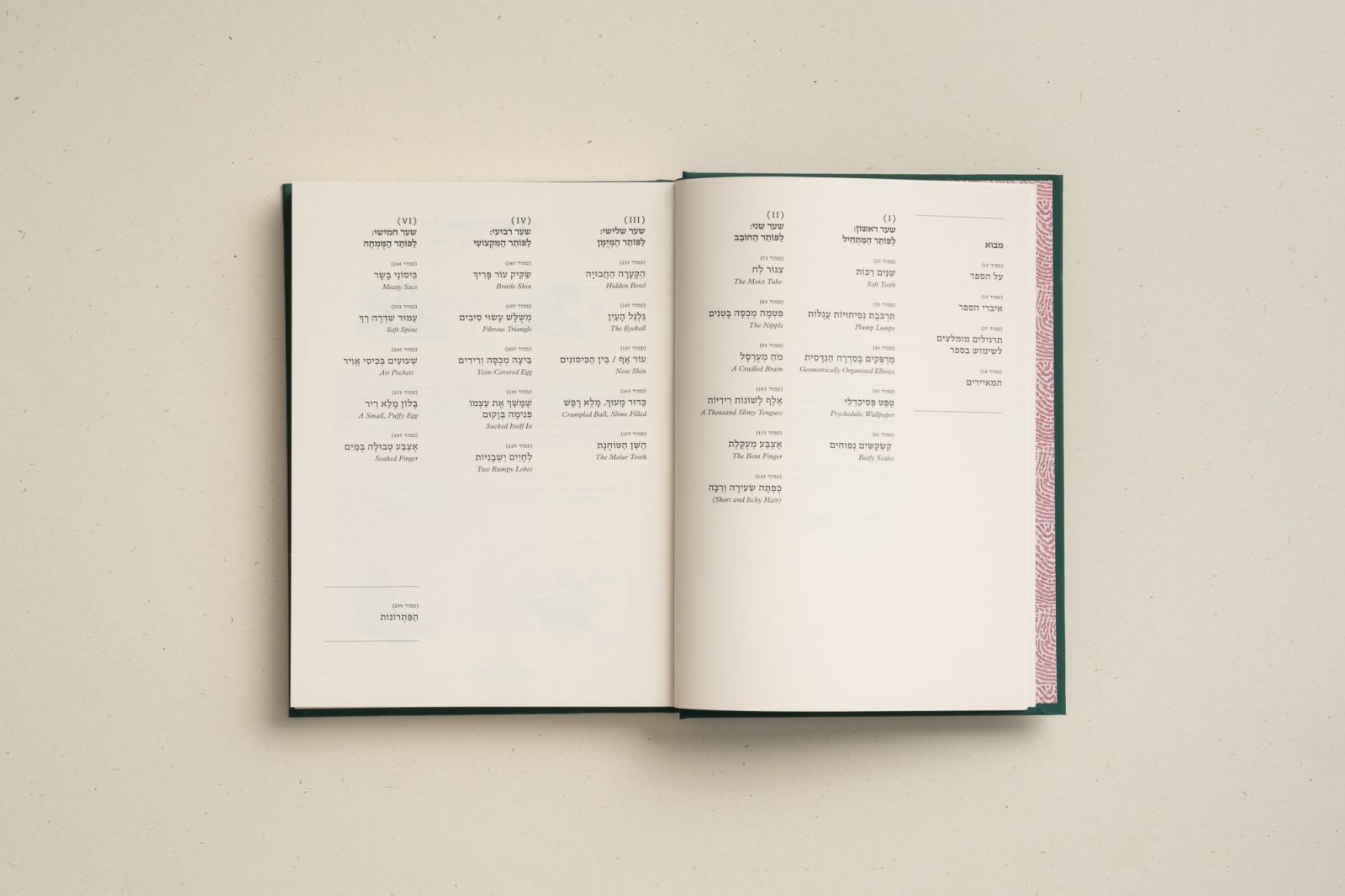

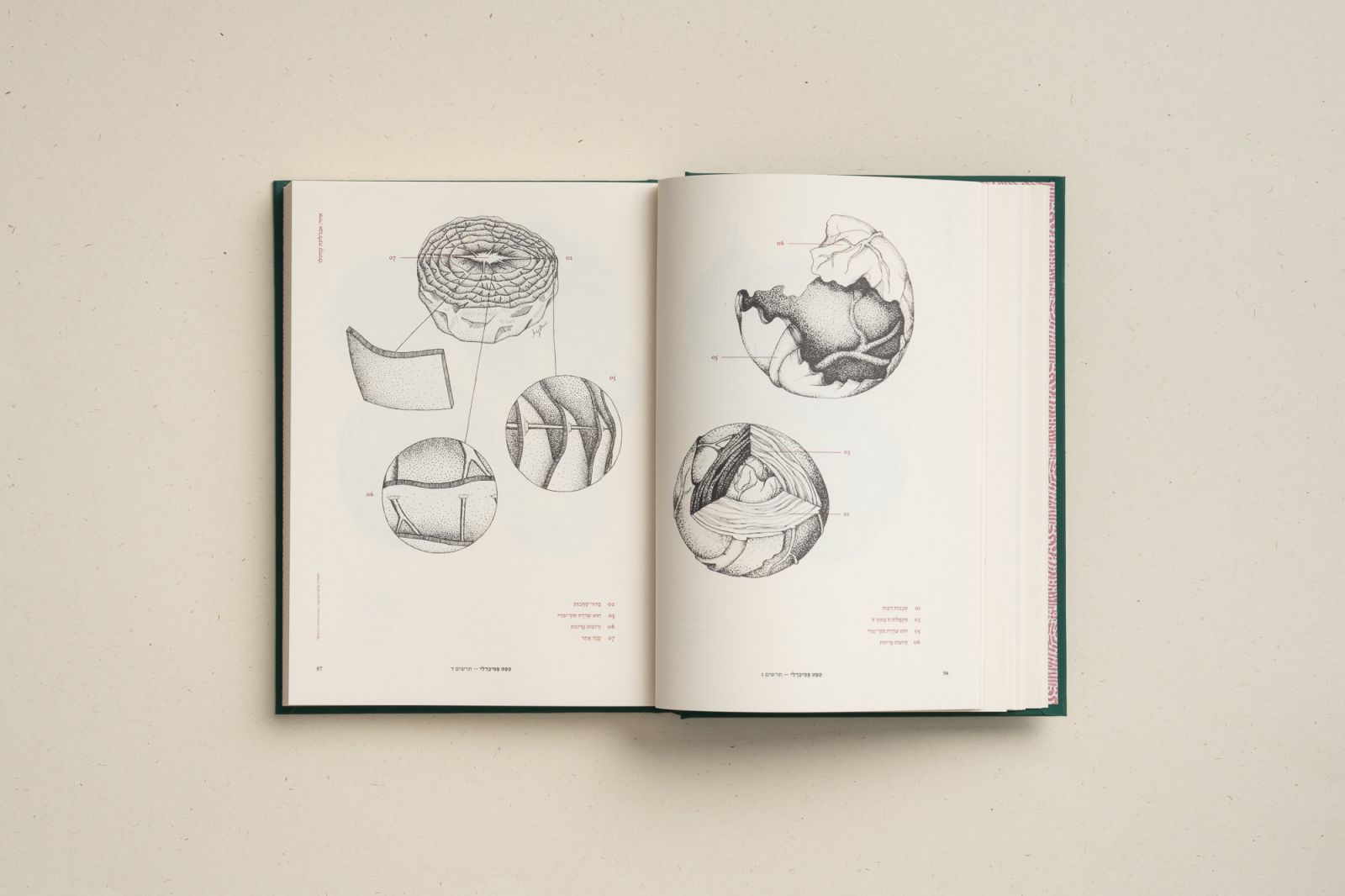

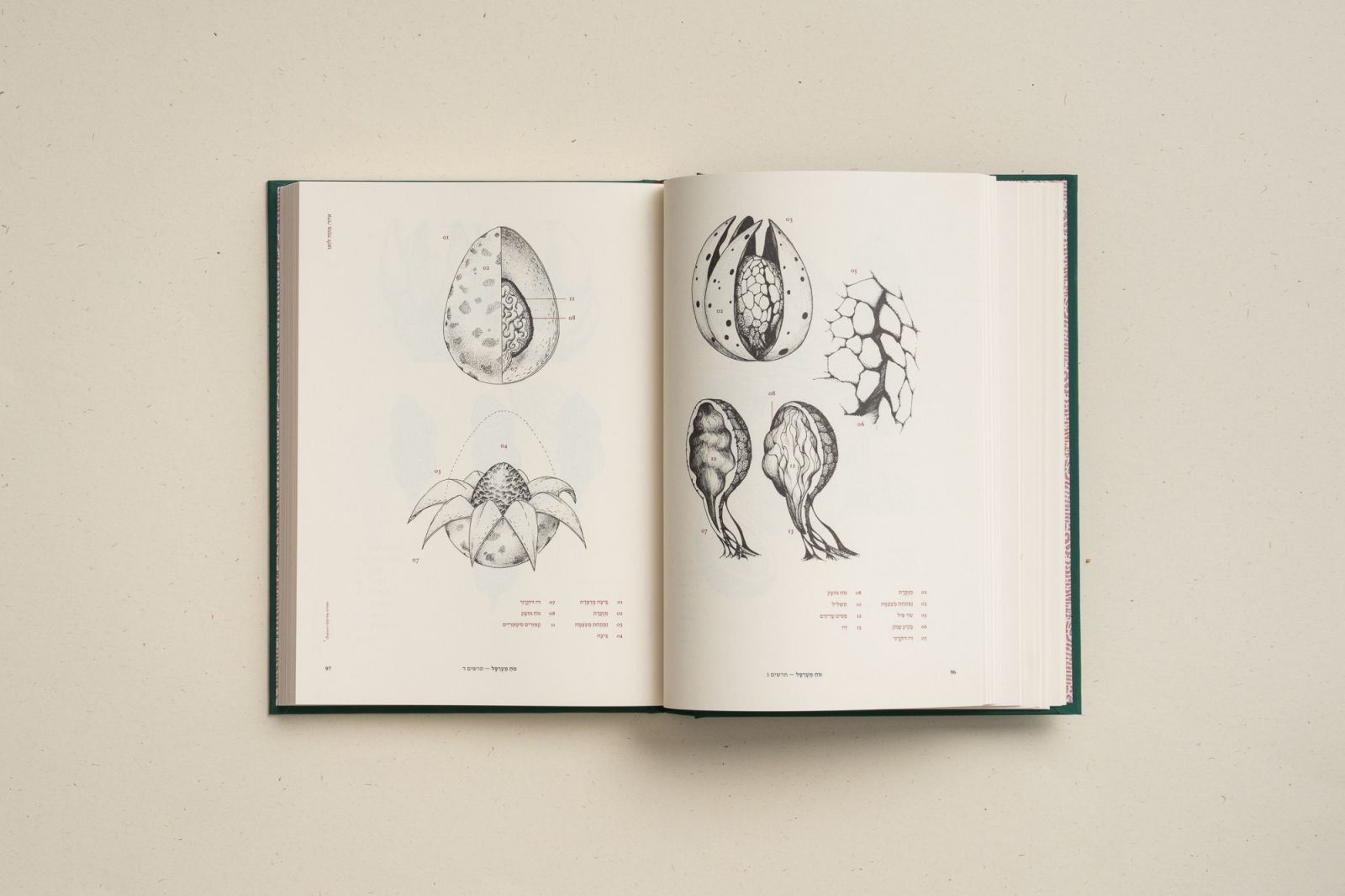

This is a book based on a recipe. The most concise version of the recipe appears in the book, as follows:

1. With your eyes closed, feel a fruit or vegetable.

2. Describe the feeling in technical terms. Aim for ambiguity.

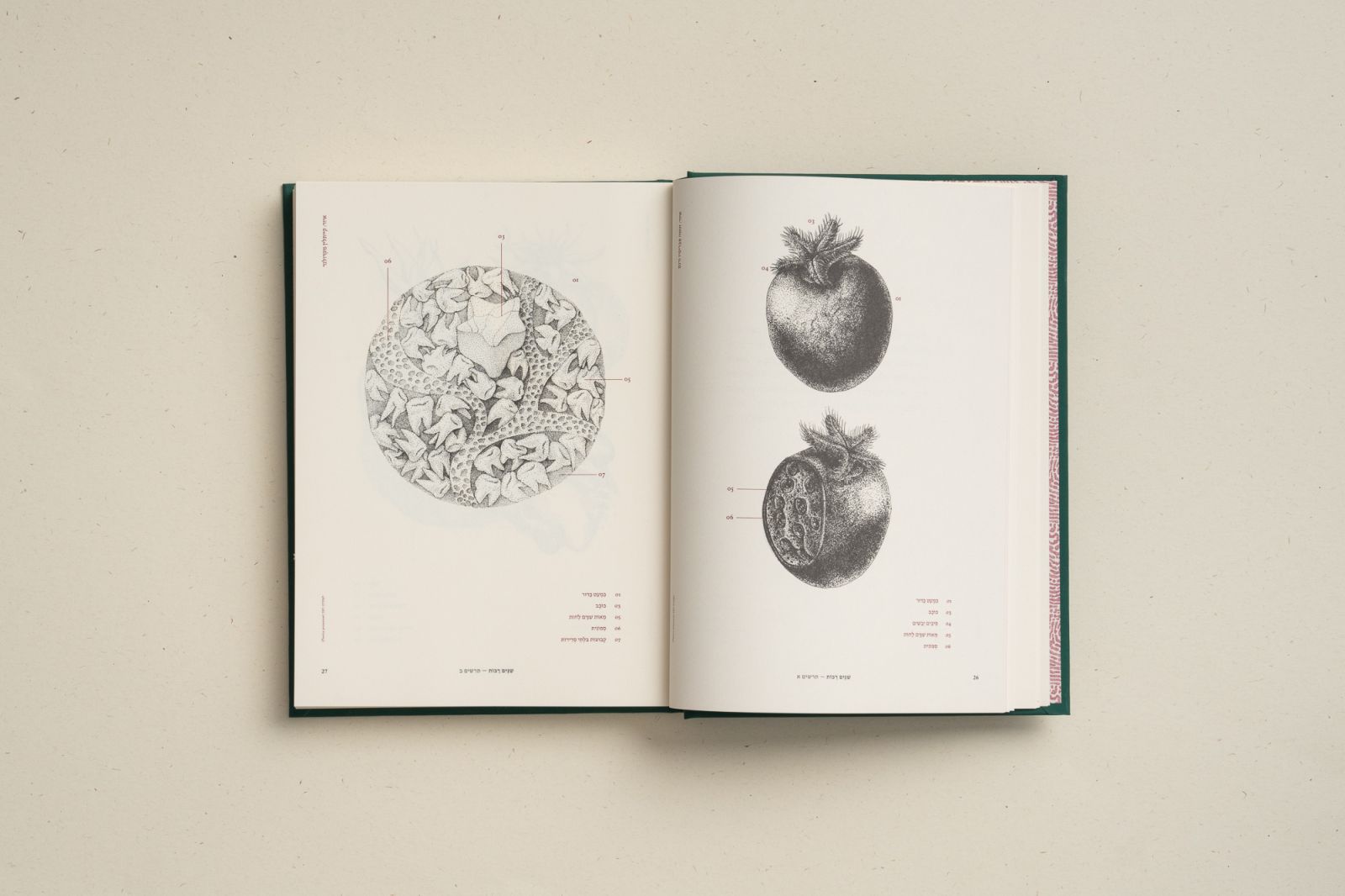

3. Locate scientific illustrators around the world. Pay them to make drawings based on your descriptions. Claim that the source of the descriptions are the hallucinations that come to you in your sleep.

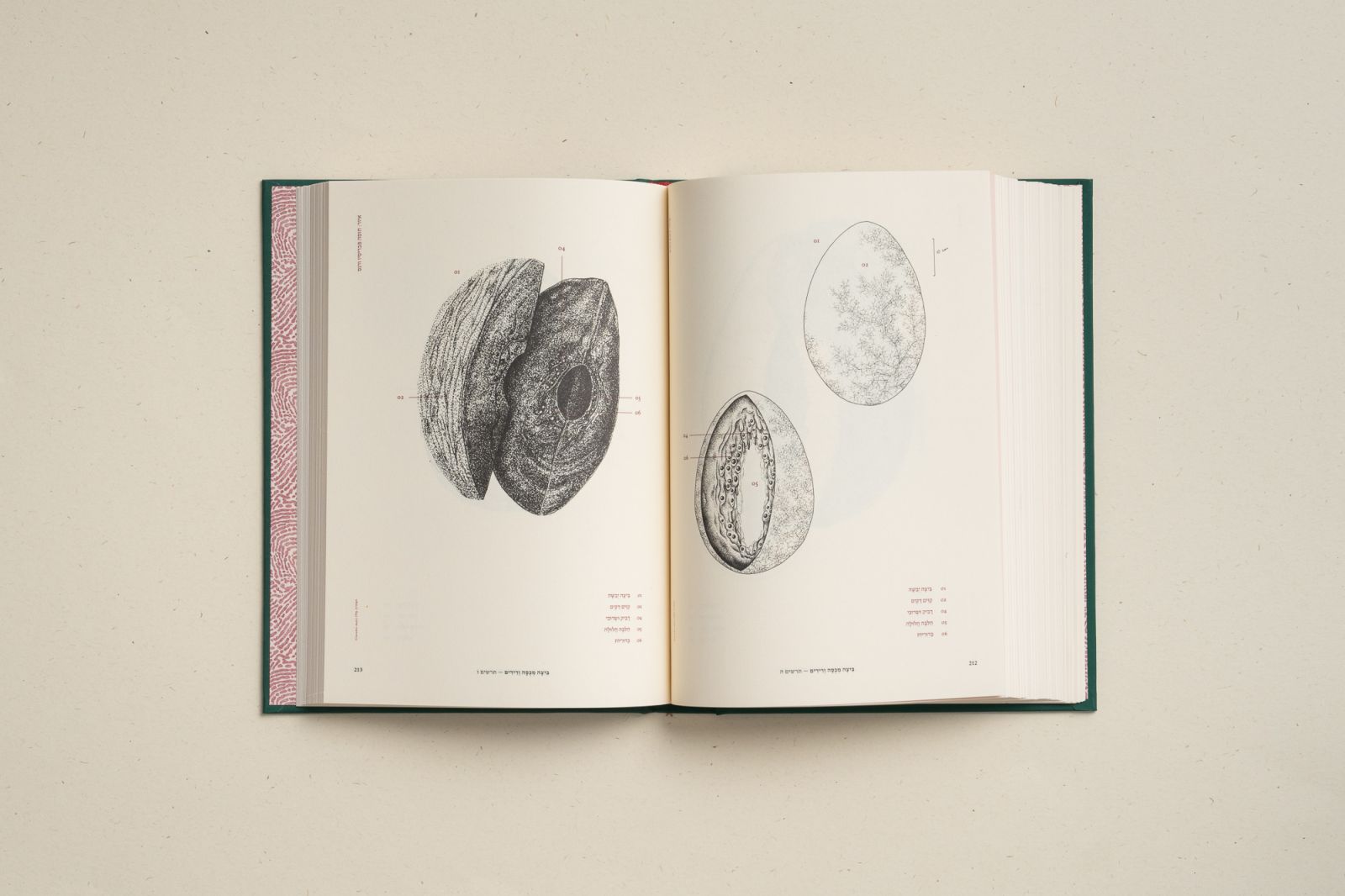

4. Be amazed by the results: drawings of mysterious science fiction creatures, slightly similar to vegetables.

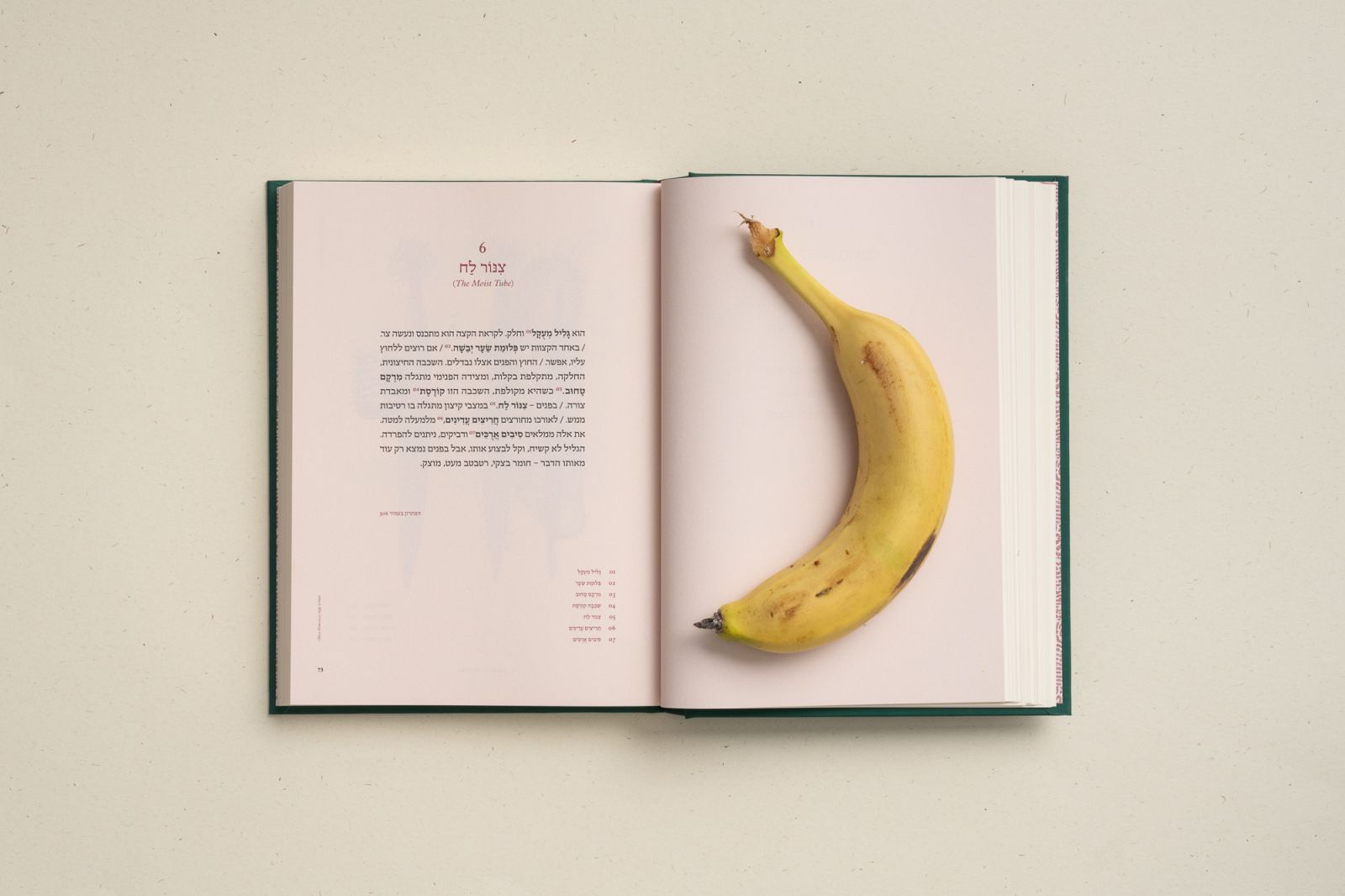

5. Ask readers to reverse the process and guess the fruit from the illustrations.

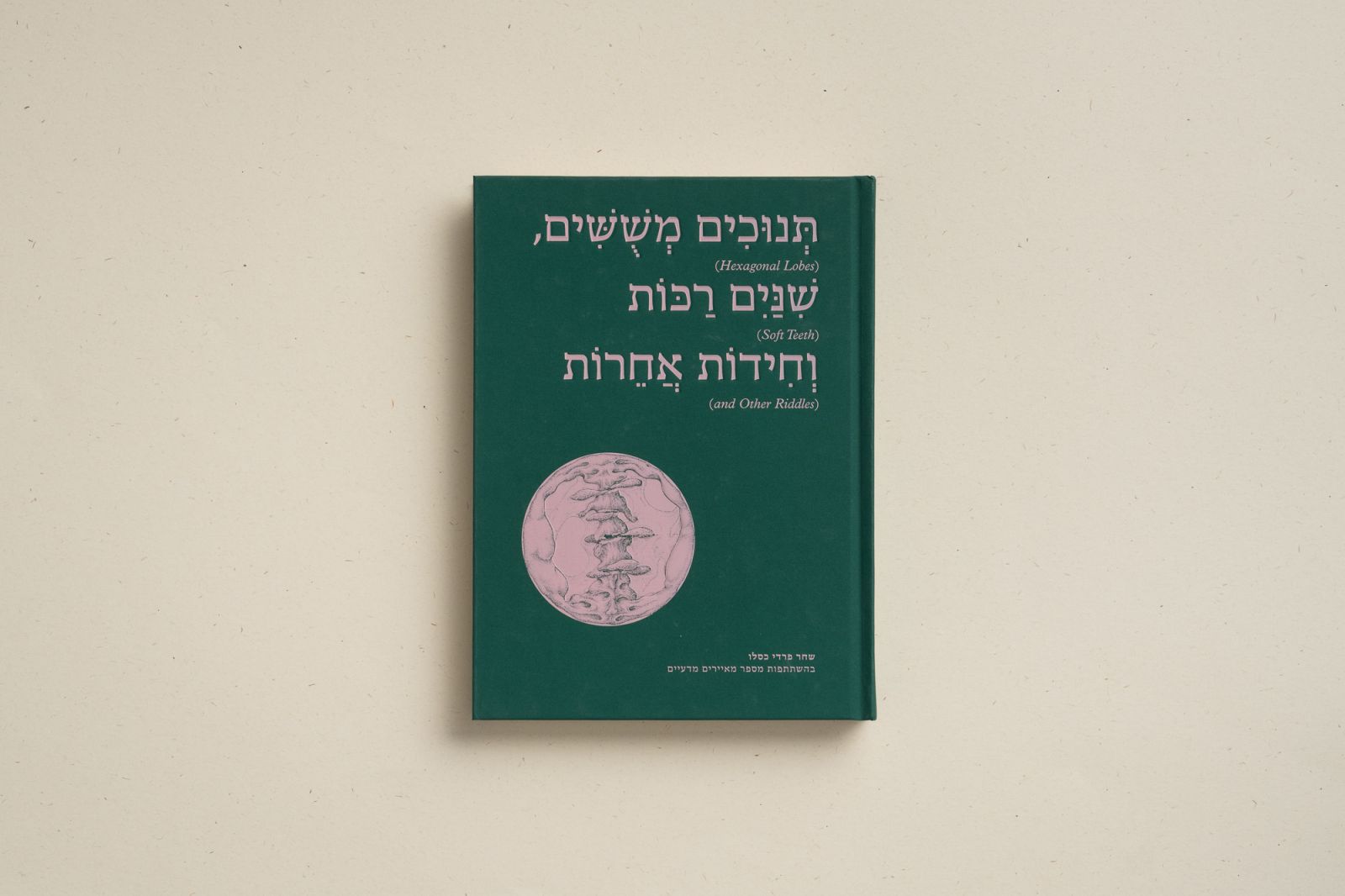

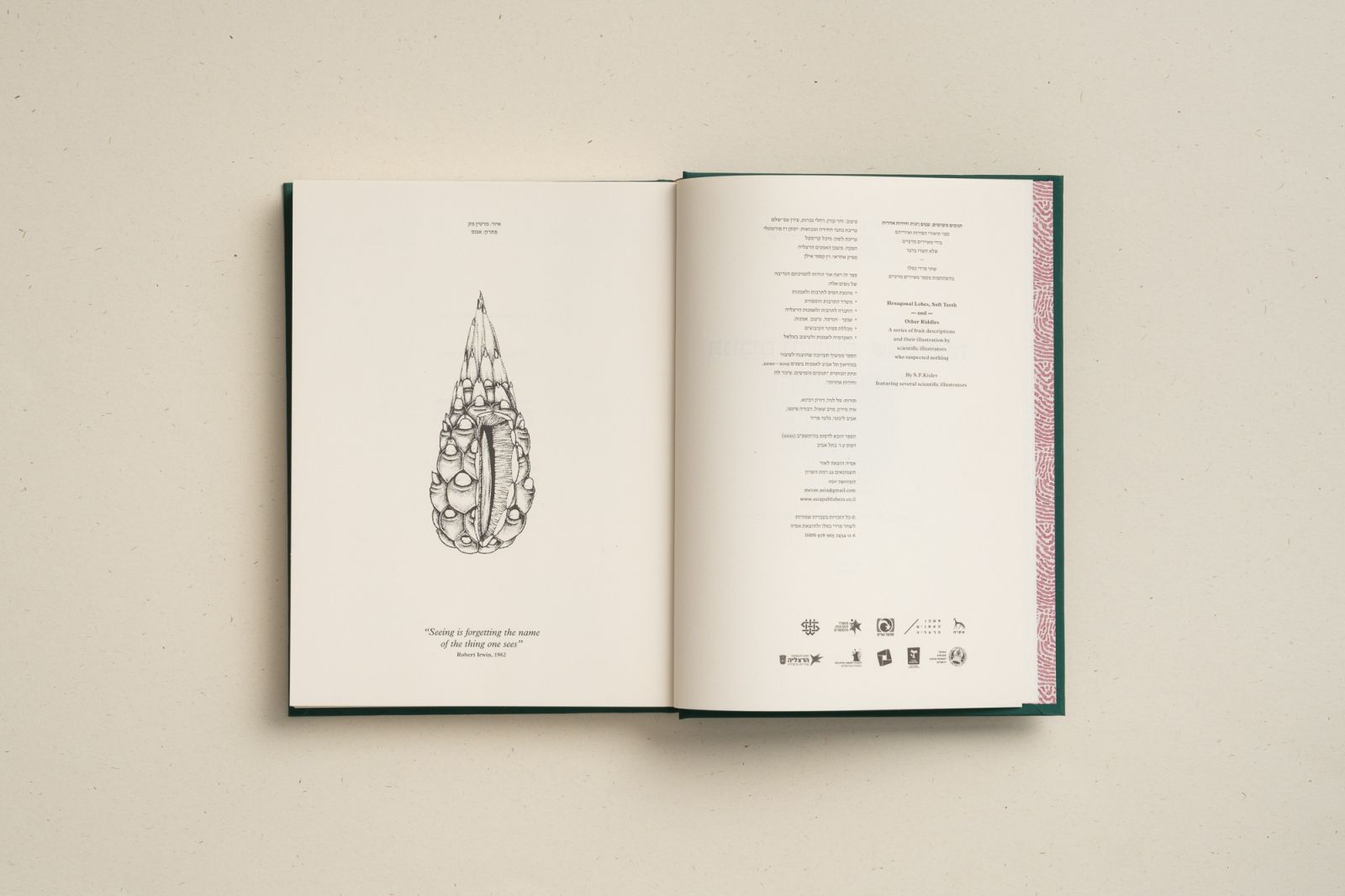

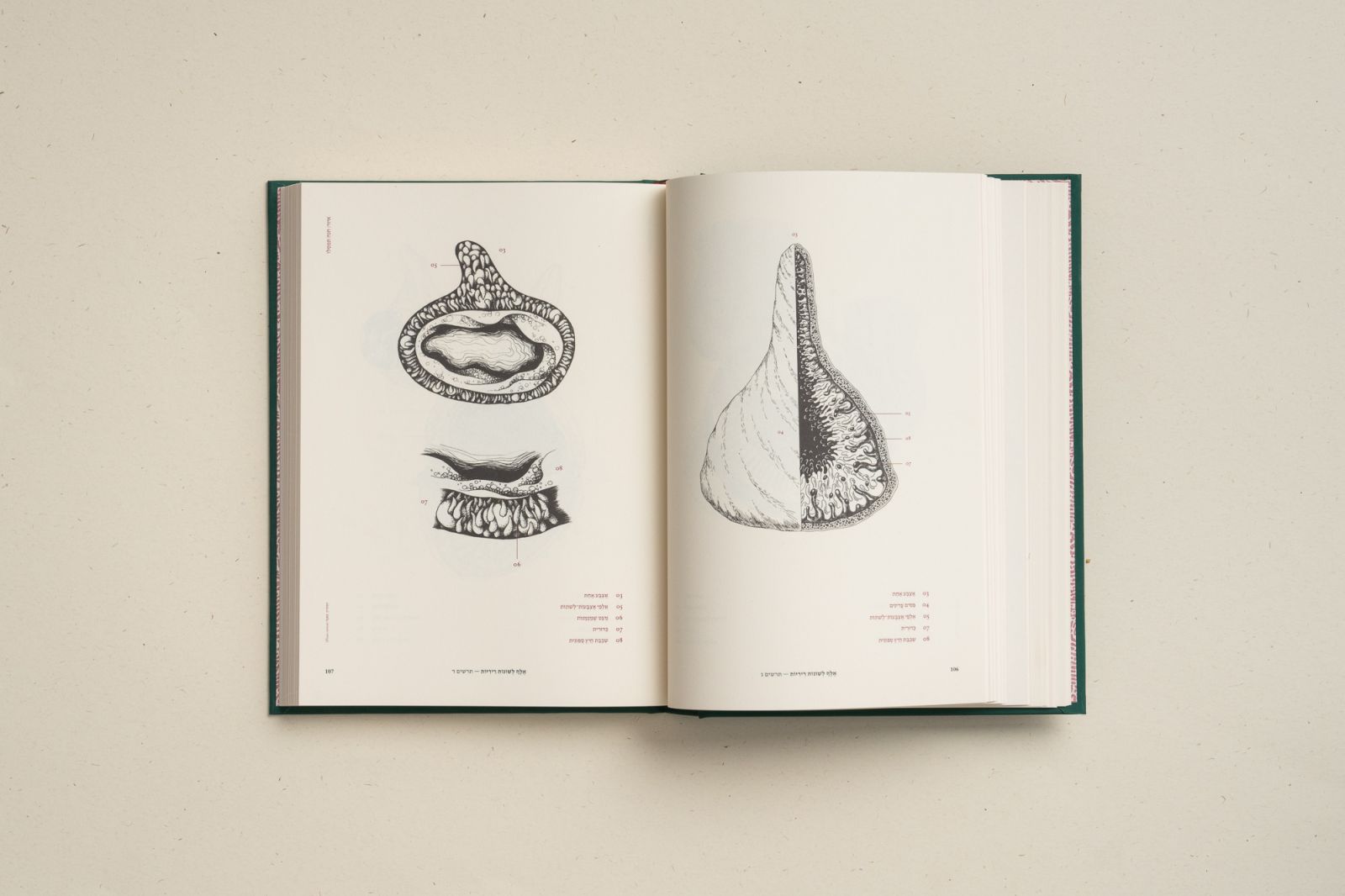

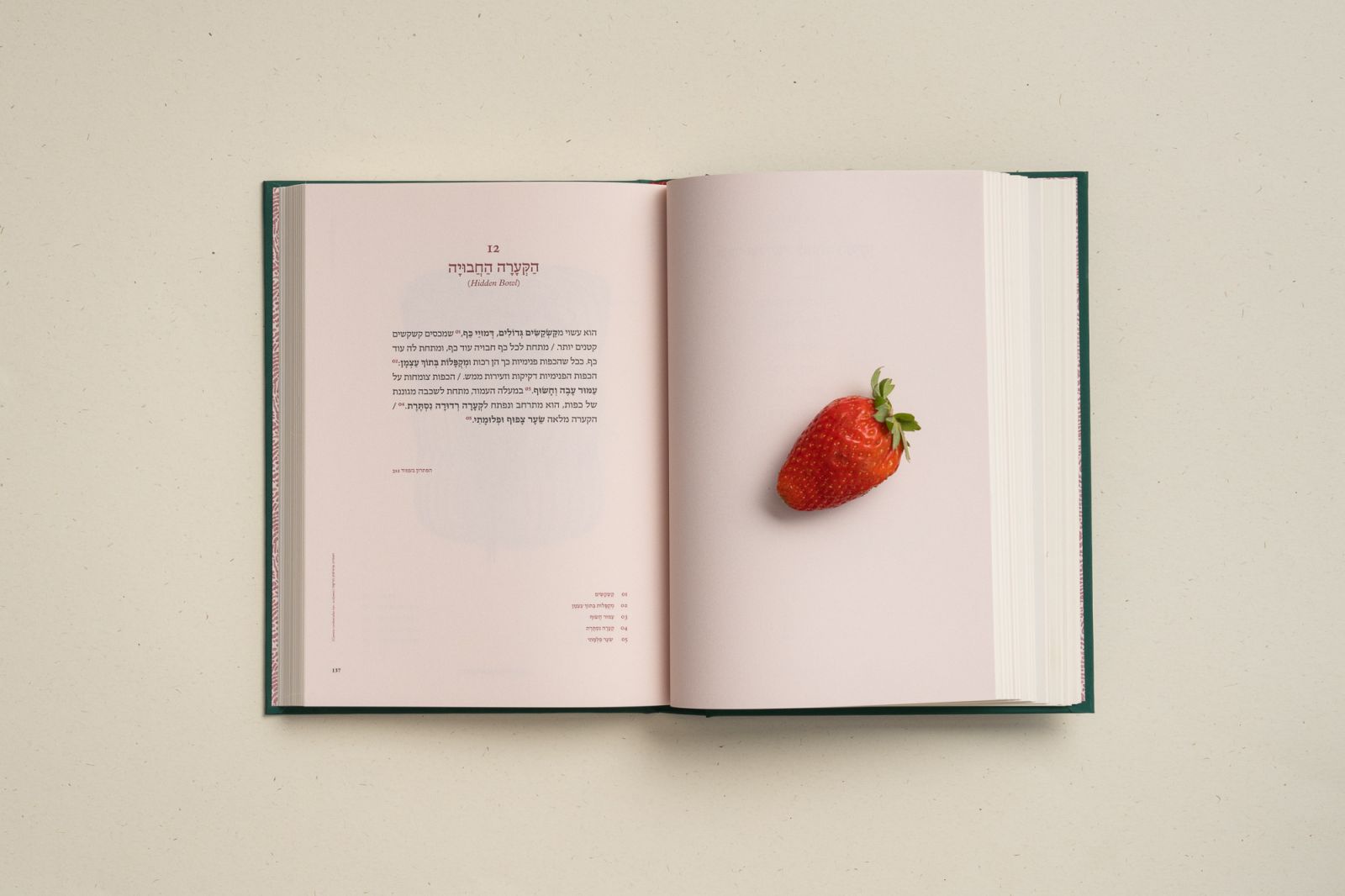

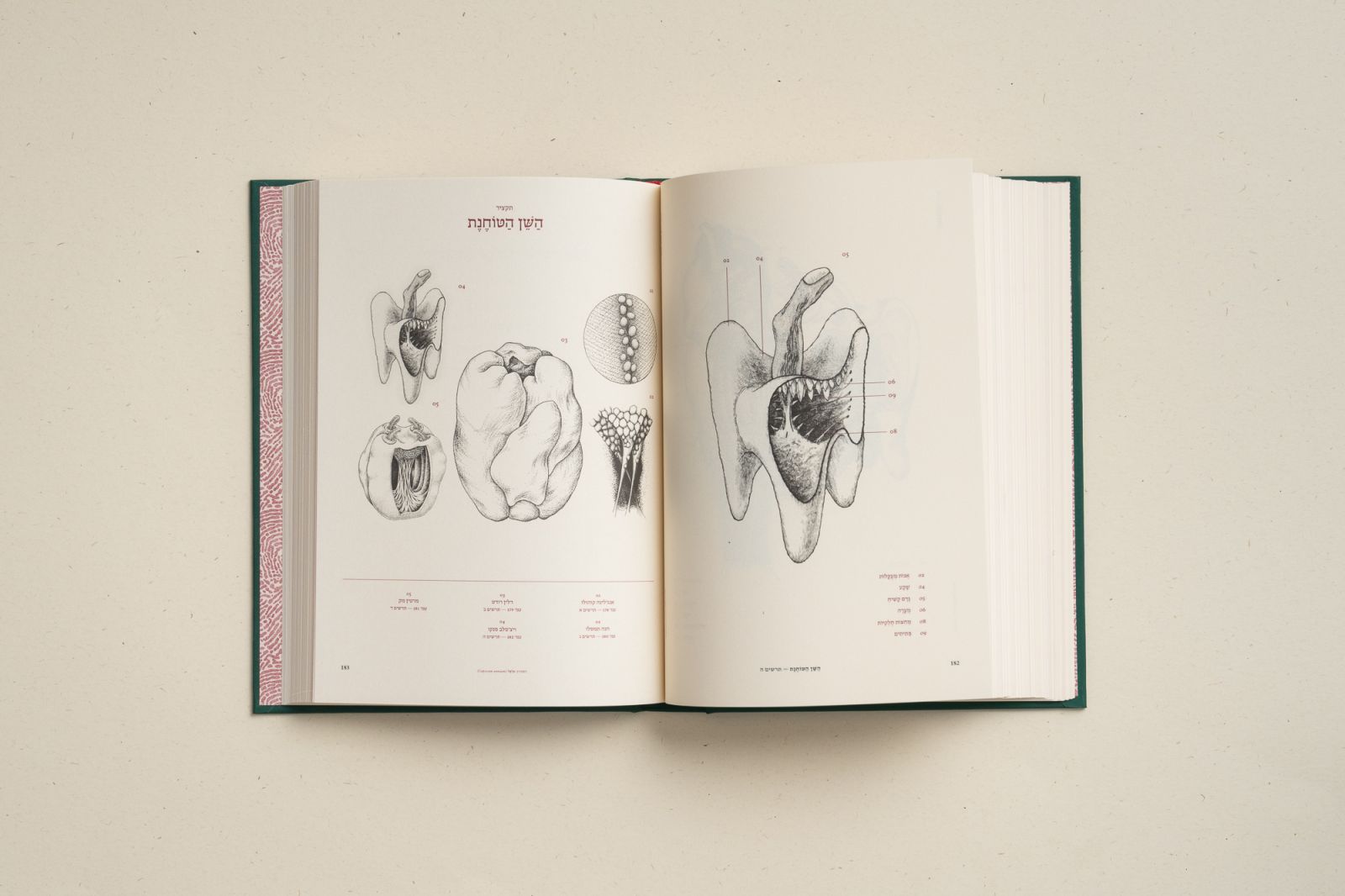

The result is a book of riddles, a collection of scientific illustrations, and a collection of imaginary fruits. The subtitle of the book can also shed light: “A series of fruit descriptions and their illustration by scientific illustrators who suspected nothing.” The book is all kinds of books: it is a book of scientific illustrations, a social game, a record of an experiment, a science fiction book, and a prank book. Perhaps a bit of a cookbook too.

You open the book with an illustration of a pineapple that does not look at all like a pineapple and a quote from the artist Robert Irwin: “Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.” It’s been said about Irwin that “one day he became addicted to his own curiosity and decided to live it.” After spending time with the book it is clear that the description fits you as well. Do you identify?

I definitely do. Working on the book was very addictive. I eagerly awaited the surprises that arrived for me in the mail from around the world. Much of it was about organizing exciting surprises for myself by mail: illustrations that did not surprise me didn’t make the cut. Illustrators that didn’t inspire wonder in me—“How did he come up with this?”—weren’t rehired. Versions that did not yield a wide range of interpretations were replaced. I admit, I was the first user of the game, and I got addicted to its thrills; the sense of adventure. Like all addicts, I too poured way too much money into my addiction; I could have purchased a decent piece of real estate in Eastern Europe with all the money I spent on illustrators.

With your permission, I will add a short and meditative exposition to the above quote. Words are, among other things, a tool for managing our limited attention resources. The world is flooded with many things that ask to be listened to or observed. In this situation, where almost everything vies for our attention, words function kind of like tiny savings devices. They teach us how to classify things: this thing is a “horse” and that thing is called a “lychee.” In this way, they make it possible to save a lot of effort at deciphering, and free up the mind for other pursuits. But, even as they do this important service for us, the words also hide a lot of details: each word masks a whole world that is going on “underneath” it, a kind of tiny bustling kingdom under the lid. There is a kind of aesthetic experience that deals with a controlled glimpse beneath the words. Still life paintings do this; haiku does it; and my book, with its modest powers, tries to do something similar. In the end, I mainly point out that hidden in the word “asparagus” is something very strange; and beautiful things too with respect to the word “peach.”

In the words of Donald Woods Winnicott, in his book Playing and Reality (1971): “Creativity consists in maintaining a key aspect of the experience of childhood throughout one’s life: the capacity to create and recreate the world. Creativity is the omnipotence of the child’s mind.” Tell me a little bit about Shachar the child? What did he play with? Did he feel omnipotent?

It’s true, there is a kind of deep childishness that is at the base of the creative mindset: it’s always a variation on “Mom, look at what I made!” Now that I’ve been entrusted with an art academy, I am preoccupied with the question of how to create an environment that does not squelch this infantilism. Apparently, some of the main anchors of higher art studies are inimical towards the childish spirit: the role of critique, for example, or the highly and mighty “intelligent conversation” that underlies most of what happens in art academies. On its face, this sounds like a safe way to destroy the child in you.

As for the feeling of omnipotence—it exists, without a doubt, but not only in a megalomaniac sense. It can be compared with the feeling of a stem cell before it has been differentiated into a specific tissue. A cell with all the possibilities open before it. One of the reasons I turned to art was to remain a kind of stem cell, to postpone the decision. It seemed to me that “art” would allow me to remain amorphous and open to metamorphoses. Last week my oldest son Noah (who's 6) asked me what I intend to be when I grow up. I grew up in South Africa in the eighties. My spiritual diet there consisted of two main components: giant snails that crawl freely on the ground, and the animated series and related toy collection “He-Man & the Masters of the Universe.”

And do you remember a stage where you promised yourself not to let that lively curiosity dry up? How do you keep it fresh?

It’s hard to answer such a pleasant question. There are no formulas here: everyone has spiritual flexibility exercises that work for them. For me, it’s a combination of an excessive affinity for games intersecting with fields of knowledge. I make it a point to import knowledge from all kinds of knowledge worlds, and look for realms of knowledge which can be used to develop new trade routes. This is an approach that the academy tends to punish: you are seen as scattered if you do not have a very narrow field of study, so much so that researchers of Kant’s second critique would feel adventurous—almost “multidisciplinary”—if they dared to go as far as the third critique. I, for my part, do not understand how people can spend a lifetime digging fortifications within one small pocket of knowledge. My hero in this regard is G.W. Leibniz, the 17th-century German polymath, and perhaps the last man who knew everything.

By the way, I came across three different books, about three different people, who were called “the last man who knew everything.” One of them is Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit polymath, who built one of the best-known cabinets of curiosities of the 17th century and patented a series of amusing and strange inventions, like the cat piano: I also consider him to be a kind of cultural hero. In any case, while the traditional academy punishes the curious who veer in a polymathic direction, art can serve as a home for them. It’s also worth mentioning, in this context, that I try to teach subjects I don’t know much about. It’s also an opportunity for me to learn, and also a kind of shared adventure: let’s read a book together. For the past three years, for example, I’ve been reading a book on biomechanics with students. Only recently did I realize that I’m not that interested in the subject.

Photography: Elad Sarig.

Curiosity like that produces, for example, a book that is made of a body and organs and not just chapters, a living and pulsating creature, with its own magnificent personality, one that is unlike anything we have seen here in Israel. It brought me back to a particularly amusing memory of the book Codex Seraphinianus, you probably know it, an illustrated encyclopedia with strange illustrations of animals, flora, anatomy and machines, all the figment of the author’s imagination who, in their honor, also invented his own writing, and it is not at all clear if it has any meaning.

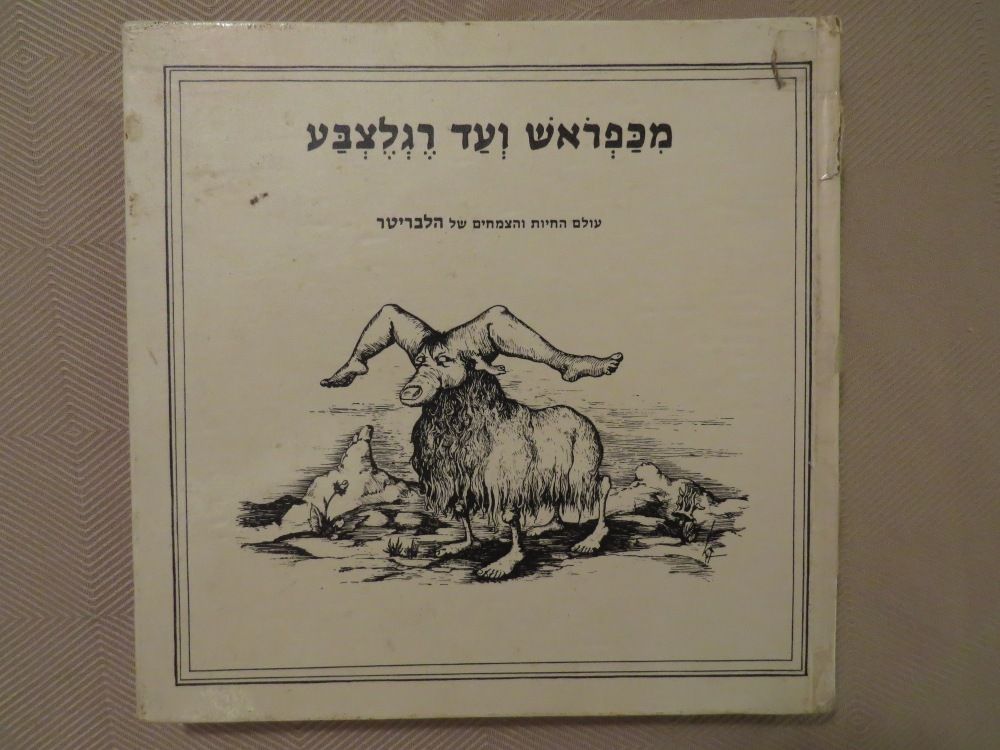

Yes, this is a highly recommended book. I would also like to refer to the book Halbritter's Animal and Plant World (1975) by German illustrator Kurt Halbritter. It was translated into Hebrew in the early 1980s and made the rounds in my childhood home (because my mother is a very good “leafer”). Today, as an adult, I can say that its texts are a bit over the top, but as a child I found them charming, and it is still worth leafing through.

I agree with you; it is totally one of the best and most original. Do you think that the tactile aspect is particularly developed in you? Or did the sensitivity develop during play?

I am responsive to textures. There’s a program called Substance Designer that allows you to design textures for 3D models, mainly for computer games. I identify with that and intend to set aside some time to devote myself to its mysteries.

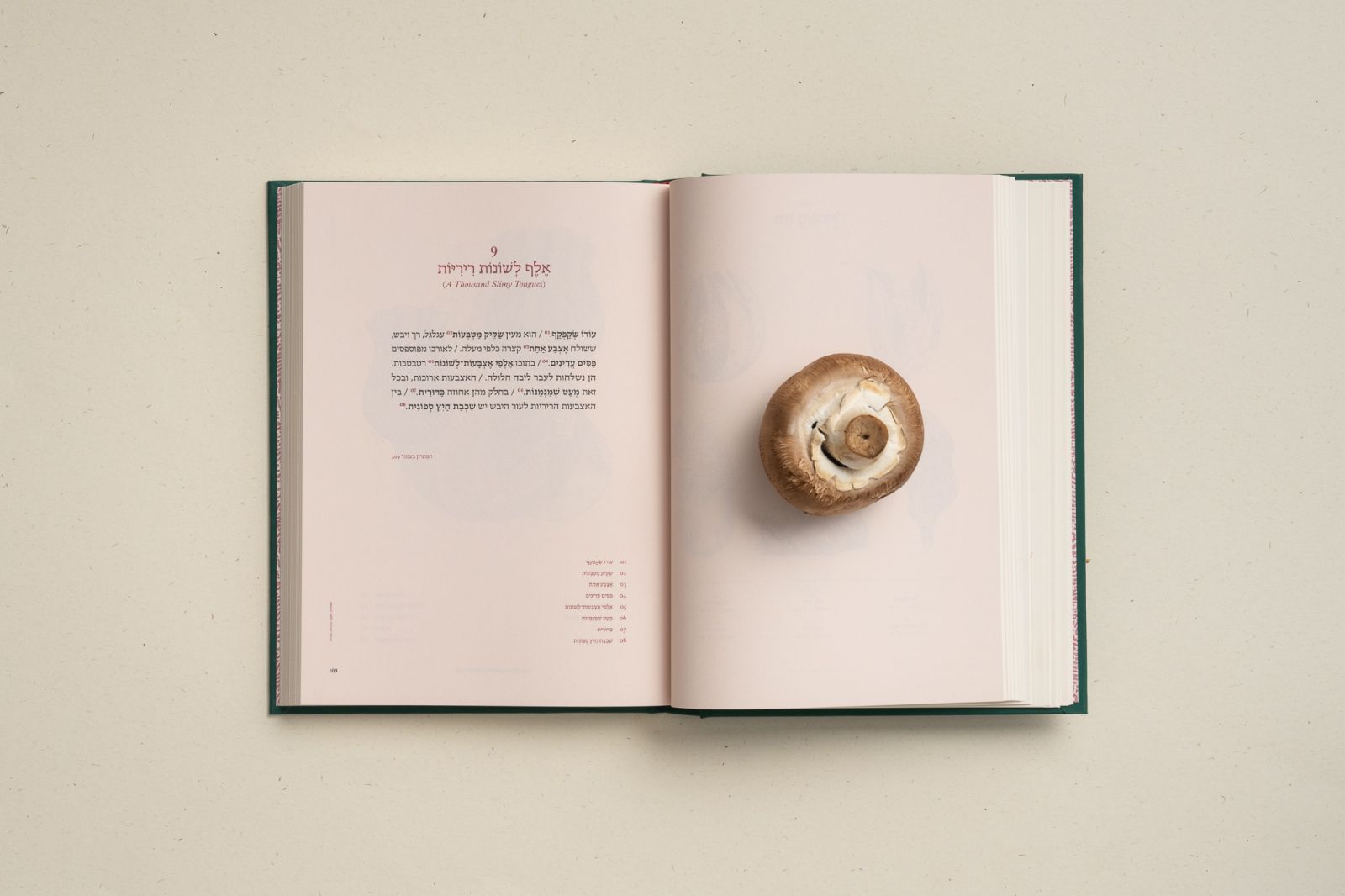

And the sensuality. This is one of the most sensual books ever made here in Israel. It starts with touching the relief of the illustration on the velvet-like cover, fingers sinking into the embossed letters and continues with the mesmerizing descriptions in your fluid Hebrew that would not shame the great poets:

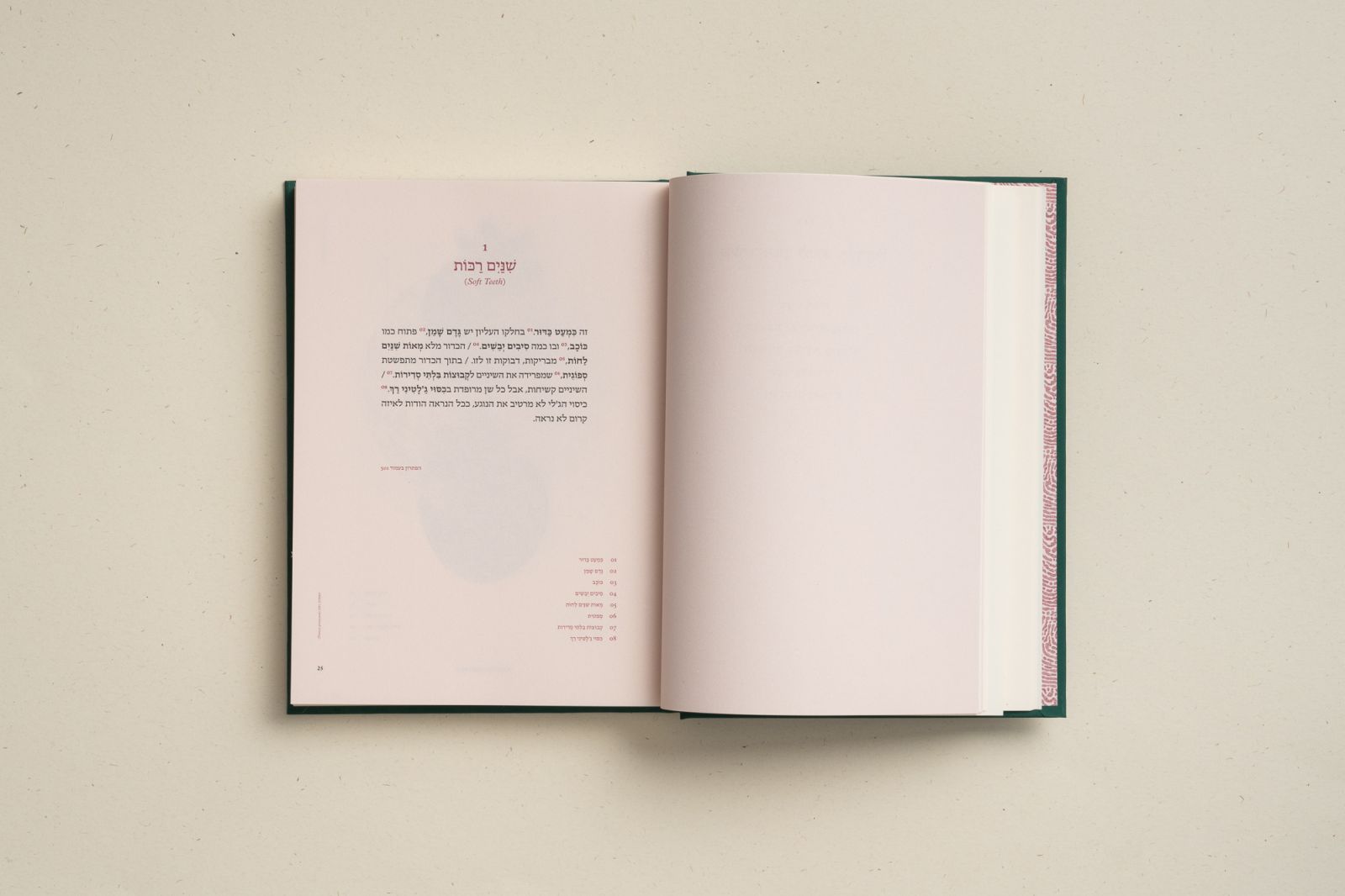

“Is it translucent? skin / is like a bag of coins / round, soft and dry, which sends one stubby finger / upwards / its length is streaked with fine stripes / inside it thousands of moist fingers-tongues / they point towards a hollow heart / the fingers are long, and yet a little fat / some grasping a sphere / there is a spongy layer between the slimy fingers and the dry skin.” (A thousand slimy tongues, p. 103).

Or this beauty: “The scales of the tip cover each other, concealing each other, fighting for the light" (from the description “elbows in an engineering series,” which for some reason are called asparagus, p. 45). Would it be fair to say that language is your true artistic tool in this book?

I would like to take this opportunity to recommend the book Thesaurus of the Hebrew Language. The lexicographer Nahum Stutchkoff worked on it for years, and it was published after his death in 1968. The book is a treasure trove of synonyms, organized by semantic fields. It’s a special pleasure. I have not come across some of the words stored in this thesaurus anywhere else, and it is quite possible that the author invented them.

Yes, the descriptions in my book are on the seam between a reference book, or instruction manual, and a poem. I’m dreading the moment when I will have to translate them into Japanese or French. I will have to find a translator who knows their stuff and likes riddles—and trust them not to ruin all the subtleties. But on the other hand, others have managed to translate even Doctor Seuss, so we’ll worry about that later.

Would you say that mainly you wrote the book?

I think I mostly orchestrated it. We don't talk enough about the beauty of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art”—a kind of mother-work that synchronizes all kinds of arts. Basically, the opera The Ring of the Nibelung can only be fully experienced in the building that Wagner built specifically for it in northern Bavaria. The opera as if includes the building within it, as a component. I’m not a fan of opera, but the work of the film director is actually similar, to orchestrate just such a comprehensive work of art.

While the photographer knows how to shoot, the actors to act, the screenwriter to tell the story, the musician to compose and so on—the director is only busy with synchronizing and orchestrating all of these into a meaningful whole. He creates through the creation of others. An architect is like that too, so is the game designer, and so am I.

In religious contexts it is sometimes customary to differentiate between types of pleasure. This also happens in philosophy: the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham (who in his will commanded that his body be stuffed and displayed to the public, and it was) distinguished between nine types of carnal pleasures, and fourteen types of pleasures in general. In my book too there are all kinds of pleasures.

It’s interesting that you went for the most conservative genre in the world of illustration, scientific illustration, and it’s there of all places that you go wild. Could you share a bit about working with a battery of illustrators, ultimately fifteen participated in the book. How did they respond to your strange request?

Illustrators are used to making commissioned works for a fee. I found some of them through platforms for finding freelancers (mainly the highly recommended Upwork), and some through deep dives on the Internet. Most of the ones I approached did not respond, and must have considered me to be a nuisance. Those who did answer were courteous, and some were really enthusiastic. For them too, after all, it was an experiment or a game. Like in scam movies, the real plan was disguised within a fake one.

For this subterfuge to work I had to be very subtle in my choice of words. Here is a challenge to readers: try to say “leaf” without using the word leaf. Make sure the description is accurate—yet ambiguous and open to different interpretations. The description should also be friendly and enjoyable to read: it is not just scaffolding but something in its own right, so you have to be careful not to annoy or tire out the reader. I didn’t always succeed in this challenge, and sometimes I stumbled. When this happened I had to change illustrators. I lost two or three just with the orange.

And why do you think there are almost no scientific illustrators here in Israel?

It seems to me that there is less respect for traditional crafts here in Israel: there aren’t many good stone sculptors or foundries. When I became interested in the industry of special effects and monsters for films, about a decade ago, I found a similar lack: there are teenagers in Delaware and Colorado who make spectacular monsters, with wrinkles, white hairs and what not.

Teenagers with good skills, ten times more than anything you can find here. This is the situation: there are entire fields without local traditions (although if you put a little effort you can find a history for scientific illustration in Israel as well: Bracha Avigad, Shmuel Haruvi, Walter Ferguson. Apart from that, what would a scientific illustrator do here? What industry would they fit into? Just as there is no environment here that sprouts scientific illustrators, there is also no environment here that could absorb them.

At the same time, there is no need for melancholy or self-flagellation: First, as my book demonstrates, the Internet has more or less eliminated the meaning of distance. All that is required is a little resourcefulness. From my place of residence in South Yafo I sent out tentacles around the world. This international caper is pleasant: the project would have been less interesting had I found the illustrators all in one place, looking for work in the Levinsky Market area. There was a moment during the work when I wondered if I should try to expand geographically as much as possible: shouldn’t I also look for illustrators in Africa, Japan, and Scandinavia? And what about Iranian scientific illustrators?

Second, scientific illustration has a glorious history, but it also has a promising future. The field of scientific visualization is a high-tech field: it involves all kinds of technologies of imaging, animation, photography, mapping, and so on. It is a field that develops methods to see what cannot be seen. That being the case, perhaps the world of scientific imaging has a chance to grow in these parts too. I won’t deny: I’m playing with my thoughts on the subject.

And one last little note about training artists: RISD [the Rhode Island School of Design] and SVA [the School for Visual Arts in New York] each have small nature museums inside the school. Students are invited to observe through microscopes, touch, take pictures, etc. This seems like a good idea to me: nature museums are just as useful for art students as they are for biology students. If by chance the manager of a nature collection is reading this conversation and wants to give up their inventory, I’d appreciate it if you’d contact me: I can find a warm home for your collection at Shenkar.

I think of the illustrated dictionaries of the past (remember this for example?), everything is accurate, one to one, like a photograph. It's beautiful but very limited. You are actually a revolutionary.

I don’t like to toot my own horn.

When you staged the exhibition Games 2013–19 at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, did you know that you would turn it into a book?

The exhibition included three independent components: the art game for toddlers “Warm Shadow,” the computer game “GWhat,” and the exhibition of riddles “Hexagonal Lobes,” etc. “Hexagonal Lobes” was born to be a book. It is very detailed, rewards patience, and requires quite a bit of time to fully master it. It’s hard to do that at in exhibition, when the space is large, your feet hurt, and strangers next to you are speaking loudly. Sometimes artists tend to forget that the exhibition format, for all its flexibility, is quite limited. There are catalogues that accompany exhibitions, but in the case of Hexagonal Lobes it is more correct to say that the exhibition accompanied the book, a bit like A Brief History of Humanity: The Exhibition (Israel Museum, 2015–16)—even if it preceded it by two years.

Photography: Elad Sarig.

How did it come about? I have a sense that it was great fun working with you on the book.

This is a question about the psychology of work, and it is more sensitive than would appear. I am relatively intense, like to involve partners in the creative processes, and not much of a compromiser. I perceive work as a kind of joint stroll in an open space of possibilities, with fluid boundaries. I also don’t really recognize the boundary between “work” and “leisure.”

I don’t have anything resembling clear studio hours. I’m never really "working": I’m (perpetually) in the midst of fun, addictive processes that are woven into life. To me it sounds quite ideal: why get into art if not to avoid “work” in the estranged sense of the term? I recently came to know, incidentally, that entrepreneurs feel similarly.

In any case, there are people who prefer to work with a clear, predefined work plan and firm boundaries. Some people do not enjoy receiving surprises outside of working hours. These are people who don’t like working with me. So, to [answer] your question: it’s fun for those who enjoy open, long processes, and are infected with enthusiasm. This is the place to mention three designers who did a masterful job: Zohar Koren, Idan Am-Shelem and Rachel Kinrot.

In an interview with Yuval Avivi and Mia Sela in Ma she’karukh [“What’s Bound”], you said that you don’t see Hexagonal Lobes as an artist’s book. Leafing demurs and asks: How so?

An “artist’s book” is, among other things, a euphemism for a book that sits in boxes in an artist’s house. How many art lovers are there who buy artist’s books? What market does it have? In any case, this is not the fate I wished for this book. On the contrary: it is my attempt to exceed the limits of “art” in the narrow sense. The book is not only intended for connoisseurs: it is intended for smart children, psychologists, judges, biologists, science fiction fans.

This is a book of puzzles and games, not a book with a curatorial text at the beginning. I hope the book reaches the hands of special education teachers, and I don’t want to discourage them with the “artist’s book” label. I even live in discomfort with the label of “artist.” Somehow, in a social dynamic that no one really wanted, art has led itself to live in a kind of bubble, which is shrinking. I wish for this book—and myself, my loved ones and my students—to leave the bubble. Of course, I mean no offense to Leafing and its noble efforts.

Who would you especially like to have leaf through this book?

Can I choose someone who is already dead?

Of course.

I wouldn’t mind if the book led to an invitation to join Olifo (it could happen, but not if I wanted it to). Because I’m watching the second season of The Righteous Gemstones now, I want Danny McBride to leaf through it too. And of course, Matthew Weiner.

What are you working on now? In addition to running Shenkar’s Multidisciplinary Art School?

Perhaps some readers have heard that Eytan Stibbe will be the second Israeli astronaut, and will spend two weeks on the International Space Station. What most readers don’t know is that in addition to various scientific experiments, Eytan will also take art with him. In a beautiful project, of which I am proud to be considered one of the originators, several artists will prepare works specifically for outer space. I am one of them. Other than that, I’m pleasantly surprised by the amount of creative energy involved in leading and re-organizing an art school. It’s also quite addictive. And finally, I am mentally preparing for the translation of the book into other languages.

Making a book is like…

I saw that the answer “it’s not like anything else” is [given] repeatedly. I think the opposite: for me it is similar to many things. Making a book, making a movie, making a game, building a building, managing a project. Anything involving orchestration has a similar nature. This insight also has pedagogical implications, which I am still trying to elucidate.

What book should we add next to our library?

I have three suggestions. First, the amusing book of epigrams If Right Now Pilates is What You Crave That's What You Should Focus On by my friend Yoni Raz Portugali, accompanied by photographs by his partner, Hilla Toony Navok, from 2018. Yoni and Toony had just started [Poraz Books], a small publishing house for “original and experimental artist’s-books that are a joy to read” so this is a good opportunity after all.

Second, my friend Alona Rodeh has published three booklets in recent years on the history and visibility of safety technologies—reflective fabrics, fire-fighting equipment, night lighting. The booklets are beautiful, thought-provoking, and are on the seam between a research manual and a work of art: they are interesting as an independent medium.

Finally, you can also try to read the book I mentioned above by Kurt Halbritter or its sequel about military armor through the ages. The author is long dead, but perhaps we can invite the publisher of Tammuz Publishing (which also no longer exists), Aharon Bar. According to Wikipedia, he went blind in the 1950s when he was engaged in dismantling mines.

Where can we get a copy of your book?

Asia Publishing, HaMigdalor and Magazin III Jaffa Books, all in Tel Aviv, and at bookstores throughout the country.

Shachar Freddy Kislev, born in 1982, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. He has a BA in philosophy from the Open University, an MFA in film and an MA in history of philosophy, both from Tel Aviv University. In 2016 he completed a Ph.D. in philosophy from the Cohen Institute at Tel Aviv University. He deals with art in a broad and flexible sense, which includes games, film and technology, as well as researching the history of philosophy in relation to the digital humanities. He is the winner of the 2015 Young Artist Award from the Ministry of Culture and Sports. A large exhibition of his works, entitled Games 2013-19, was presented at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 2019–20. Since 2017, he has served as the Chair of the Union of Visual Artists, and since 2020 is the Head of the Multidisciplinary Art School at the Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art.

״The result is a book of riddles, a collection of scientific illustrations, and a collection of imaginary fruits. The subtitle of the book can also shed light: “A series of fruit descriptions and their illustration by scientific illustrators who suspected nothing.” The book is all kinds of books: it is a book of scientific illustrations, a social game, a record of an experiment, a science fiction book, and a prank book. Perhaps a bit of a cookbook too.״

״They teach us how to classify things: this thing is a “horse” and that thing is called a “lychee.” In this way, they make it possible to save a lot of effort at deciphering and free up the mind for other pursuits. But, even as they do this important service for us, the words also hide a lot of details."

"Everyone has spiritual flexibility exercises that work for them. For me, it’s a combination of an excessive affinity for games intersecting with fields of knowledge. I don't understand how people can spend a lifetime digging fortifications within one small pocket of knowledge. My hero in this regard is G.W. Leibniz, the 17th-century German polymath, and perhaps the last man who knew everything."

"Scientific illustration has a glorious history, but it also has a promising future. The field of scientific visualization is a high-tech field: it involves all kinds of technologies of imaging, animation, photography, mapping and so on. It is a field that develops methods to see what cannot be seen."