How does a book come into the world?

This is a book that’s a sort of mid-career retrospective. It started very simply; I wanted to publish an artist’s book, I applied to the Israeli Lottery for Culture and the Arts, was awarded a grant and began. The first thing I did, intuitively, was to call the curator Joshua Simon and tell him that I wanted his help. He would be in charge of the book. Unlike artworks, I had no vision. My vision was Joshua’s smiling face. Thanks to him the book reached the excellent Italian publisher Mousse; I’ve been following their art magazines for years and adore their products. There was something in this process that required me to just let go. A book is a big deal. And texts are way over my head. I’m not one of those artists who writes and puts things into words. I make art and always work with writers. In general, I believe that if there’s someone in the room who understands something better than me, then the responsibility shifts to them. Immediately we realized that we wanted to work with the incredible designer and graphic artist Avi Bohbot and so we began.

The first thing that caught my eye has to do with the editing of the book. At the beginning of the book, there is behind-the-scenes documentation of some of your key works, and then the work Happy Hunting Grounds (2019) at the center of which is broken glass. The book ends with two images featuring intact glass in an open space from the series Double Perspective (2014). I don’t know if this is a good place to start, but it’s such a smart choice in my opinion, one which presents a central axis in your work and in the book.

This is an excellent place to start because the broken glass is the work I presented just before the beginning of the coronavirus. I was in the midst of a sequence of exhibitions over several years: among them the solo exhibition Beyond the Distance – A Distance (RawArt Gallery 2018), The Perfect Crime at CCA (the Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv), The Shadow (RawArt Gallery, 2016), the work The Red Star, which was included in the exhibition curated by Joshua Simon, Children Want Communism, shown at the Bat Yam Museum and then in Berlin (Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien).

After that, I was awarded a grant for an exhibition from Artis (Revulsion, 2019), and everything was very tight. I felt the urge to smash something. It was the climax of a process that began in the final year of my graduate studies at HaMidrasha School of Art. So the shattering that kicks off the book is first and foremost me shattering vis-a-vis myself, and I knew somehow that after that I’d enter a new kind of cocoon.

So, I took this office chair and smashed it into glass that is ostensibly the glass that frames a photograph in a white cube space, but is actually the glass that is the front of a shop, bank, or restaurant; I was influenced then by the social riots in London in 2011. Uzi Tzur wrote very nicely about it in his column in Haaretz, that it was “a vision of the end of the capitalist era preserved in a bubble like a fossil, as a future historical museum artifact.” Facing it was another work, The Man without Qualities, which also appears at the beginning of the book, and is made of plastic, but which I wanted to have look like it was made of glass.

The intention was that it wouldn’t have any characteristics, gender or otherwise, in order to talk about how money and its movement dominate the world in so many ways in our lives, and of course in the art world. Maybe The Man without Qualities is the one who threw the chair at the glass. It’s always some anonymous figure that starts the biggest revolutions.

And the glass at the end of the book?

These are two works in which I placed mirrors in the middle of the road and photographed them directly, as if the glass were a runway model, even though it’s the furthest thing from that. Many of my works look as if they have been lightly photoshopped or digitally retouched, even though most of the time they haven’t, and that gap, between what actually happens and the basic assumptions and prejudices in this age of photographic excess, is beautiful to me. I like when people suspect me of computer work, and more than that, I love disproving those suspicions.

So I thought about how I would make a collage within a photograph, and produce two perspectives from one point of view in the same frame. It’s essentially a mirror of a mirror of a mirror. The mirror offers a single perspective of a reflection, and the camera offers a counter-perspective of documentation. The mirrors I photographed are huge—over five meters wide and three meters high. And behind were people who held them and almost collapsed under the weight. The photographed place is “nowhere” and “everywhere”; whoever gets it, gets it, or as they say—whoever gets it, it’s their problem.

For me, the pendulum motion of the book’s beginning and end resonates Alma Yitzhaki’s claim, which she formulated so beautifully in her text (see: "Beyond The Distance – A Body"): Through the practices you’ve created, you enable some kind of “rehabilitation” of the experience of the body in the digital age, and also face the impossible challenge of restoring the status of the image as material. Is that sort of the “happy ending” of the book? The glass becomes whole again, “participating” in the game of representation.

I’ll go back to the beginning for a moment. I build “dioramas”—although these aren’t exactly classic dioramas—and glass is a main material in my work, which also relates to my preoccupation with economics. It offers us an inward perspective. Through the glass, we peek into the enterprises of oppression, industrialization, enslavement, exploitation, and profit. It is the collaborator of capitalism. Ever since I chose glass as a dominant raw material, I’ve been looking for ways to manipulate it, how to find the sculpture that is within the photograph. I started out as a sculptor working with materials. I also studied architecture in high school, but photography took hold of me somehow, perhaps because of its immediacy, because it requires less material, it’s less bombastic, much more democratic. I was entranced by its democracy.

How did your practice begin? Was there a eureka moment?

At HaMidrasha, I made quite a few works with walls, all kinds of initial attempts at combining photography and sculpture. Just so that you can understand how much I love walls, whenever I see discarded drywall on the street, I caress it. As part of my attempt to find my own language, I combined walls and photography separately in immature attempts to understand how to handle photography in a different, non-traditional way, not a white wall facing a framed photograph. In my continuing studies with the artist Roee Rosen, I did one work that was a leap forward for me, called Cyan Magenta Yellow. This is a work made of an 80 cm long aquarium, which I filled with water into which I poured a substance that muddied them, and then placed lighting on both sides, which produced streaks of light in the three primary colors. It made the water look like smoke. I framed this aquarium as a photograph and displayed this installation among other two-dimensional photographs on a 13-meter wall. I remember when Roee walked into the exhibition and asked me, “Wait, where’s the 3-D work?” I suddenly realized that I had succeeded in making what I had been looking for all these years. It was like finding the love of my life.

The story of this revelation appears in your interview with Joshua in the book. You called the joint text “Cameras.” It’s charming, because you turn the 3D material reality into a kind of “camera,” or “photographic array.”

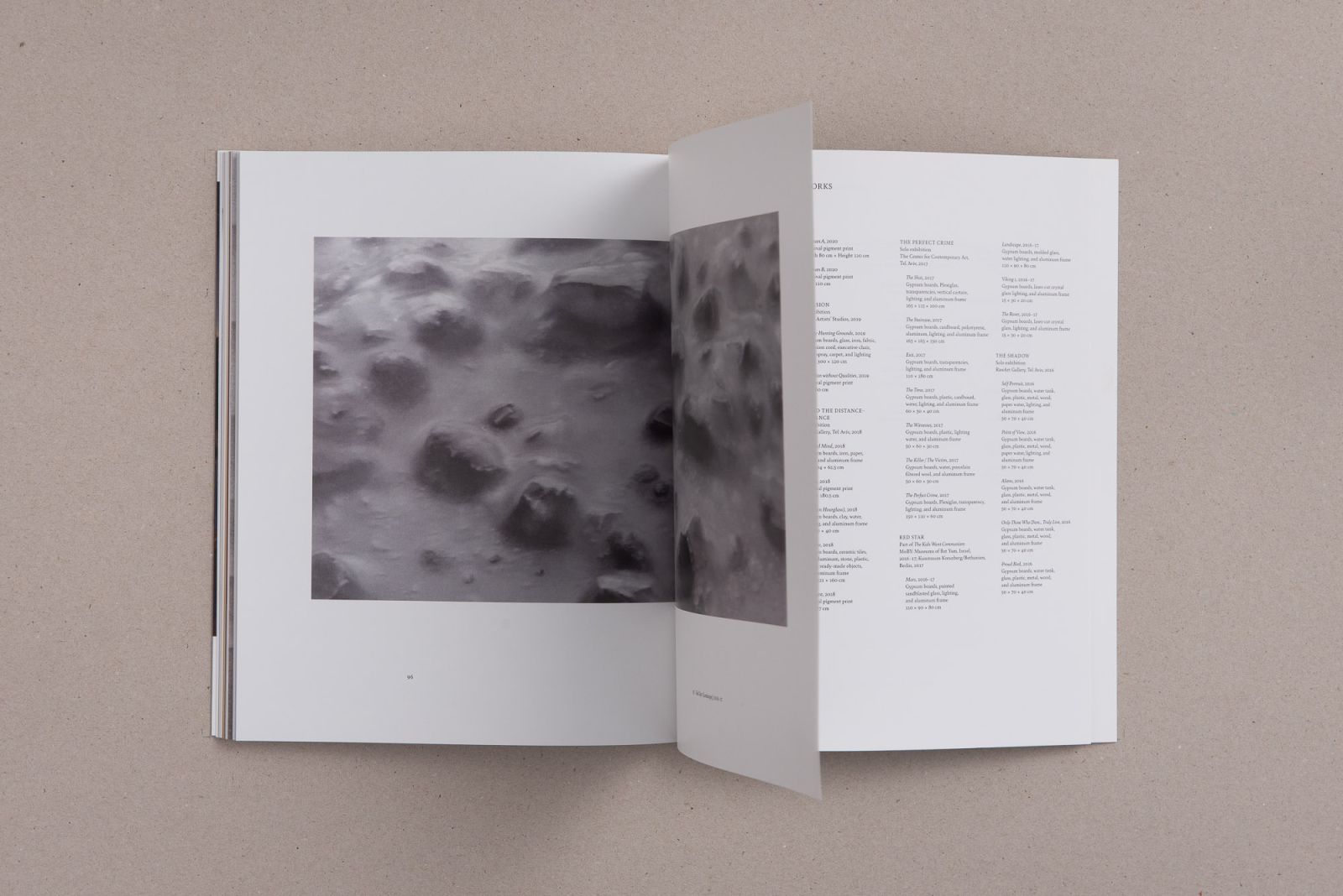

What you call “arrays” has to do with how images exist in our head, or in mine, and how they’re translated from the collective consciousness into art. I’ll tell you about another example in this context. When I was invited to participate in the exhibition Children Want Communism, the first image that came to mind was The Red Star. I come from a family that fled communism. I was thinking of science fiction books that were very popular in Soviet countries until the middle of the 20th century, that were all talking about a utopian place that communism creates on Mars. I researched the first photographs ever taken of Mars in color by the Viking 1 spacecraft. The first photograph taken from space, and the second photograph of the surface of the planet taken by the lander’s space probe. And of course, no person has really seen Mars with their own eyes, just as no person has really experienced communism in the utopian sense of the word.

In the work, I made a reconstruction in laser cut of the spacecraft and the probe, which I placed inside a crystal stone, and also an image of the red star itself and its rough surface. Of course, there are questions here about ideas and their realization and utopias, and the dream of a future. I used a lot of glass and water here too, because glass is a material that I feel is connected with distant planets and galaxies.

What was it like to suddenly imagine a book—which is a three-dimensional object—that presents these kinds of images?

Avi Bohbot immediately understood my mindset. I think my visual research can be defined as a “philosophy of scale.” It’s a constant movement between spaces, so we didn’t detail the size of the works in the book except for at the end. I preferred to make the leafing experience mysterious, ambiguous, alive—without any outmoded commitment to sizes or dimensions.

Having leafed through the book, I can say that there’s a constant sense of wanting to see things in “reality,” an attempt to figure out “how” you did “what” you did.

I am very happy to hear that. It’s important to me that the experience of looking at the works not be clear or deciphered completely. For example, the image Iron and Mind led me to study Opt-Art, a movement from the beginning of the 20th century, which dealt with three-dimensional illusions in painting and sculpture, and the material existence of images in space. In general, there are works I hope I’ll make again.

It’s great that you say “I’m going to make them again.” We are so used to images being produced and reproduced in digital forms today. In what way are you influenced by 19th-century historical dioramas?

I have always been intrigued and influenced by nature museums and in particular by the Museum of Natural History in New York. When it was pointed out to me that what I was doing was dioramas, I said okay, that’s interesting, and I mulled it over. This definition saves me a lot of explaining, but I think what I’m making aren’t really dioramas that are engaged with miniaturization. A diorama puts an entire world into a box. I take a detail from the world and focus on flattening it. That is not the same thing.

In dioramas, the result is very clear and distinct, both in terms of the craft and of the practical message. With mine, there’s always some confusion. For example, in the work of the stairs at the beginning of the book. I took an iconic and cinematic, almost Hitchcockian image of a stairwell, reduced it and fit it into a wall in the gallery space. It’s a work the viewer is almost sucked into. This is not an educational diorama placed in a nature museum. It’s a nightmare. In the exhibition Shadow, I again used an aquarium filled with water to create the image of an airplane in free-fall (Proud Bird). It works on the diorama principle of minimizing, but only in a formal sense. The airplane is a toy plane made of metal, the sky is water, and together they produce a kind of implied catastrophe. It’s hard to imagine that it’s not photography, and the horrible magic of this work really isn’t transmittable in print or in a book.

Yes, you have to see it in person.

Apropos in person, the opening of this exhibition was on September 11, 2016. It’s a pretty direct coincidence, no? Maybe a little too direct, but it wasn’t my fault; I didn’t set the date of the opening. Another coincidence with one of my works was with an image of an empty tower based on the Meier Tower on the corner of Rothschild Boulevard and Allenby Street. To me, it’s so tragic that with all this real estate and money, these huge towers stand empty, and you see like two rooms lit up in all the darkness. The images in my exhibitions are organized quite intuitively around a central idea.

In the case of Shadow, it was the spectrum of wealth and poverty. Along with an image of a Ferrari, police cars, the Meier Tower and the falling plane, there was also a “self-portrait,” which was a three-dimensional sculpture of a mannequin wearing a hoodie hidden inside a window display. Its face breaks through the darkness, like a generic criminal the police racially profile. The closer you get to the work you actually see yourself because the figure is dark and you are reflected in the glass—this most unfamiliar face becomes familiar.

You erase the face in many of your works, sometimes elongating the neck to hide them. What do you have to say in your defense?

I think there are many reasons for this, which I find difficult to lay out hierarchically. First of all when I take a picture of you, you look at me. I wondered if the same feeling could be achieved of “someone looking back at me” without the presence of eyes in the image. That is, as a viewer, you know there is a face there, and you look for the eyes but they aren’t there, there is an absent presence. What replaces them is a piece of skin. The second reason has to do with the fact that my mother is blind, and most of the time I’m really dealing with the experience of not seeing. Maybe I create palpable three-dimensional images that can be felt to compensate for her lack of sight, but this hypothesis verges on the Freudian.

There are lots of questions about what we can actually know, about the epistemic limits of knowledge in your work.

Yes, we can just assume and say that everything is an illusion because we are in the age of the deep fake. The book features a series of portraits from about a decade ago that challenge the “body,” and ask what’s a “face,” and how can we know anything at all. It might be the case that I was trying to make an analog deep fake even back then, but in a distorted, grotesque, surrealistic way that’s unfaithful to the original.

I get it completely. Apropos portraits and bodies, the cover of the book features a “futuristic” image of a figure and some kind of “space” landscape. What are these?

These are the last two photos I presented before the coronavirus at RawArt Gallery (2020). The work is called Shaman. Now I call it Goodbye My Love 1 + 2. I usually change the names of works. For example, the work Rachel was formerly called Miami. The French fold on the cover that Avi Bohbot designed, the way the image is cut, is perfect in my opinion. It deepens and corresponds with the three-dimensional experience of the images.

I always say that the name of a book is like a secret, would you let us in on it?

Usually, once I have a name for an exhibition I know I’m heading somewhere, even if the path is unclear. This is the initial drive to start researching, which gives me confidence in the process. The exhibition Beyond the Distance – A Distance didn’t have a title until there wasn’t any choice left. I was under terrible pressure. I felt this was a special exhibition after the daughter of good friends passed away suddenly. An exhibition born from their great loss, which I observed with great sorrow from the sidelines. I needed something that would embrace the process.

Then I attended a lecture about the poet Yocheved Bat Miriam who had lost her son at a young age. After he died, she vowed not to write anymore and walked around Tel Aviv in the 1950s dressed only in black. Her writing is astonishing, and the line “Beyond the distance – a distance” comes from one of her poems. As soon as I heard it, I knew it was the name of the exhibition. Every time we searched for a title for the book, we came back to that line, until we just gave in. This sentence captured us. For me, it describes what I do, I’m constantly creating distance, and then a bit more distance.

Making a book is like…

Pinching yourself really hard.

What book should we add next to our library?

Naama Arad and Tchelet Ram.

Where can readers buy your book?

At the RawArt Gallery, and on the publisher’s website.

Noa Yafe, b. 1978, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. She received her BFA and MFA from HaMidrasha Faculty of Arts, Beit Berl College. Yafe’s works blur the boundaries between photography, sculpture, installation, and architecture. In her work, she deals with possibilities of vision and knowledge, including through the construction of three-dimensional dioramas that seem like two-dimensional photographs. In recent years, she has participated in several group exhibitions and staged a number of solo exhibitions: Revulsion, at the Tel Aviv Artist Studios (2019); Beyond the Distance - A Distance at Raw Art Gallery (2018); The Perfect Crime at the CCA (2017); The Shadow at Raw Art Gallery (2016).

״The gap between what actually happens and the basic assumptions and prejudices in this age of photographic excess, is beautiful to me. I like when people suspect me of computer work, and more than that, I love disproving those suspicions.״

"When I was invited to participate in the exhibition Children Want Communism, the first image that came to mind was The Red Star. I come from a family that fled communism. I researched the first photographs ever taken of Mars in color by the Viking 1 spacecraft. And of course no person has really seen Mars with their own eyes, just as no person has really experienced communism in the utopian sense of the word."