The book is modest in size and weight, and with a refined cover. I spent hours poring over it. What I had assumed was a catalog for the exhibition Looters [CCA Tel Aviv, 2017] turned out to be an in-depth, rich, poetic, and tragic study that stands on its own. It’s a book that deals with your practices as an artist, which you used to create several solo exhibitions. How did this book come into the world?

Actually, I’d prefer to begin in the present. We’re meeting three-and-a-half years after the book was released, which feel like especially long years. Maybe years always seem that way, and perhaps the coronavirus disrupted a thing or two in terms of our sense of time. In addition, it seems to me that conversing about old projects is quite often not simple, and sometimes even complex. The same is true here. The book came out together with the Looters exhibition, but from the distance of time, I can say that this book summed up a longer chapter of activity, after which something changed a little in my work as an artist, but it may be too early still for me to put this change into words.

I think of this book as a collection of meditations about the intricate relationship between the concept of “plunder” and the artistic artifact. With the Looters exhibition, I tried to remap my work, and I noticed that in hindsight one can identify a return, as if [I had been] possessed by the question of plunder—the question of the ownership of objects expropriated from a person, place or foreign body, and integrated into the fabric of the looter’s identity.

At no point did I make a conscious decision to deal with this issue. It was more of a preoccupation that stealthily crept in and exposed old projects in a new light. In working on the book, I tried not to place the artworks at the center, but rather the concept of plunder that haunts them and me. Hence, even though it’s an artist’s book, I tried to juxtapose the works like someone who deciphers the concept from different perspectives. At the same time, I wanted to broaden the discussion, recognizing the limitations of my point of view. I invited four writers from different schools of thought—Elinore Darzi, Gish Amit, Kifeh Abdul Halim and Morag Kersel—who unravel the concept of plunder from different economic, social and philosophical perspectives and through diverse test cases.

While working on the book and the exhibition I was busy trying to map out the rich terminology surrounding the subject of robbery. I tried to understand not only the lexical but also the cultural differences of the Hebrew terms for plunder, robbery, looting, theft, stealing, and taking (and to some extent also appropriation) and of their English equivalents, among them the words pilfer, plunder, loot, and booty.

In conjunction with that, one of the interesting things was trying to decide which term to use for the book and which for the exhibition. The Hebrew term “shalal” [plunder] was eventually chosen because of its similarity to the Hebrew word “tashlil” which means photographic negative, which emphasized photography as an act of negation and reversal. The book is an ideational premise on which the show stands. Through the exhibition, I tried to look at the questions underlying the term “antiquities theft” in general and in terms of this land [Palestine / Israel] in particular.

And you chose to do this by looking at the archives of photographs and objects of the Antiquities Authority’s Theft Prevention Unit. The title itself elicits a smile.

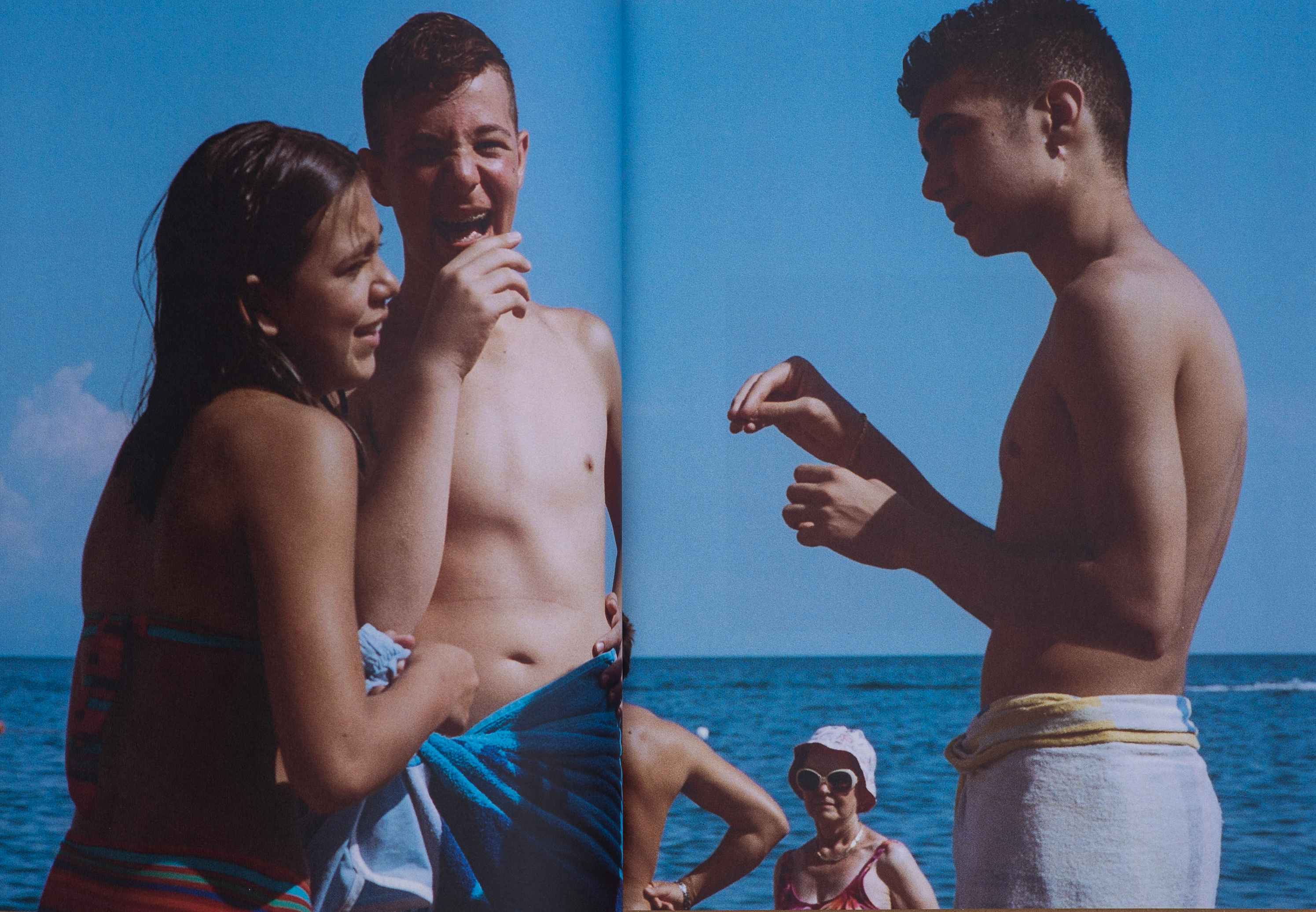

Yes. The unit tasked with guarding archeological sites from looting has amassed a unique archive of photographs, including photographs of the tools used by antiquities looters, looted sites, and the unit’s raids on homes and sites. The second collection originating from the unit’s activities is a collection of objects—a collection of stolen objects confiscated from their looters and stored in the state’s national treasures storerooms. The exhibition was built as a single installation with different chapters whose raw materials are the photographs and objects originating from the Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit. As with my other works, the installation was tied in with the question of scale. The photographs were enlarged to life size thereby transforming the subjects in the photographs into face-to-face encounters with the viewers.

Curated Chen Tamir, 2018.

Installation shots: Yuval Hai.

There are other projects in the book that deal with the same theme. Can you tell us about them?

Another project in the book that clearly deals with plunder is Abandoned Property. In that project, I went to Kibbutz Yad Mordechai and examined objects scattered about in the kibbutz that are still, to this day, labeled “abandoned property”—a term derived from the description of Palestinian property, whose owners were either exiled or killed during and after the 1948 war. I tried to examine the objects of almost no economic value through the new narratives woven around them, that is, how their new owners perceive them as part of their own identity.

In the Plunder project, from which (also) the book’s title was drawn, I processed an archival photograph of an exhibition of weapons taken as spoils of war and displayed at the Petah Tikva Museum. The weapons were stored in the museum alongside the art collection until the early 2000s. The photograph, from 1957, is in the city’s archive and shows the narrow space where dozens of weapons were displayed next to the caption “plunder.”

In the work, I recreated the photographed space by covering the gallery walls in a photo that was enlarged to the scale of one to one, but I digitally erased all the weapons from the image and left only the accompanying caption “plunder” as testimony of what originally filled the void. In my Non Private Collection project, I presented a collection of stolen photographs given to me given by a family friend who had taken them from his neighbor’s house when he was a teenager in Tel Aviv in the 1960s. The photographs capture a variety of historical events, including the 1948 War, the Suez Crisis, and the Eichmann trial, and the work deals with his guilt over the theft of the photographs and how their story as objects intertwines with their content on the one hand and his life story on the other.

The book also includes projects where the concept of plunder seems foreign to them at first, but upon a closer read, another interesting layer emerged. One such project is “Works from the Palestine Exploration Fund Archives.” The PEF was established in London in 1865 and became the first European institution to focus on researching the area where Israel and Palestine are located today. The foundation strived to create scientific connections between the region’s actual landscapes and those of the Bible, thus “proving” the existence of the Holy Land, a concept that still influences the region’s politics and reality.

Another is “The Hawks and the Sparrows.” The project focused on the museum complex in the city of Petah Tikva, which includes a number of exhibition, commemoration, and preservation spaces. Throughout the project, the various and separated spaces were categorically surveyed, and various objects rewoven into the display space. Among other things, were a pile of deer antlers; a cut out from a photograph of the mosaic floor from the nearby Yad Lebanim building; a plaster torso of a naked woman by Jacob Loutchnsky (1969); a photograph of a bird that has lost its feathers; a transparent display mannequin showing the female anatomy; and a taxidermy lion.

It’s a lot of effort to gather together so many projects and think about how they work in the format of a book. How long and with whom did you work on it?

Work on the book took about a year and a half and was done alongside the wonderful curator Chen Tamir, who held my hand and thought things through with me. The team over at the Israeli Center for Digital Art, led by production manager Diana Shoef, also participated in the production. Also, working alongside Dana Gez and Nomi Geiger from Studio Gimel 2 who designed the book was enlightening and heartwarming.

Refugeeism and looting are implied from the book, and especially a sober acknowledgment of them. As an artist, what was your role in the face of these? What was important for you that happen in the book in connection to that?

I have doubts about (my) ability to create art out of nothing. I need something tangible to activate me, to trigger the creation. In this sense, I’m not an artist locked in a studio. On the contrary, I need to be in motion, to see and read, to find hooks in the world to cling to, to react to and act on. In that sense, I’m constantly stealing, using materials that are not “mine.” Hence, the way I treat things in the world leaves an open channel in their ability to motivate me and generate an action, and in my ability to “use” them. With refugeeism, another thing happens when I enter places that activate me; I try to wear two hats: on the one hand, devote myself to them until I fall in love, and on the other hand, remain skeptical of any object and story. This dual state is a state of refugeeism, of simultaneously being inside and outside of things. I think the book is a kind of invitation to this dual reading mode, both with respect to the works themselves, and to the book itself.

Curated by Ravit Harari, Kibutz Yad-Mordechi, Gallery Dana.

Installation shots by Avi Levi.

You break down the inconceivable political reality into the smallest of elements, what the eye did not even know it could see. I find a lot of freedom in your work—freedom and courage. Everything is open for grabs, even in police archives. But, tell me, in technical terms, how did you get the Israeli police to show you such secret archival material?

You’re talking about freedom and courage, I’ll answer first by talking about fear. In the creative process, there are moments of sheer horror. They’re first and foremost from within, from the fear that a work simply doesn’t hold water, the fear that it will not crystallize into something worth seeing, worth discussing, worth thinking about. A friend recently told me that this fear is present in the very way I work, in this very process of dismantling that you’re asking about, which during the process momentarily brings the things I’m looking at to a state of almost complete emptiness because I removed the layers from it and cut it, just before I retell it.

It seems to me that in the creative process more than anything else there’s a small, personal attempt to get closer in order to decipher something of that “inconceivable political reality.” This is so that it will be possible to see it—something that is often frightening. Which is why the very desire to “see” is in conflict. The strange relationship of devotion and rejection that I conduct with those institutions in which I operate is what allows me to get inside them. I used the term “falling in love” before and not in vain; I think that it’s real.

I’m well aware of the political conditions that afford me—as a white woman and a Jew in a racist country—access to spaces that are more difficult for others to enter. The institution’s gatekeepers are more open to accepting me; they’re less suspicious of me. My explorations take time, and the process of sobering up from falling in love can lead to crises with the institution at later stages. Inevitably, at some point, I’m expelled from a space in one way or another. In this sense, the institutions themselves maintain a duality with respect to me, and allow me to see up to a certain point.

Specifically in the case of Looters, which you asked about, I was acquainted with the Antiquities Authority Theft Prevention Unit from a previous project I had worked on together with the artist Patrick Hough. We visited the unit in order to understand more deeply the subject of antiquities trading in Israel. The conversation took place in English, which also has a certain aura in institutional interaction. So, when I asked to look at the unit’s photos, I already knew who to contact and they knew me.

I will note that these are photographs whose role is twofold—on the one hand they are used as evidence in police files, and on the other hand they are used by the press for public relations. When I received them, they were out of context; that is, I had no metadata: who took the photo, when, and where. In this sense, the institution guarded itself, because from the photograph itself and without further information you can only understand up to a certain point. This boundary interested me. After going there three times and photographing, I was expelled on the pretext that I was taking up too many resources—more than they had—and that they had real work to do.

And another thing I find interesting in connection to your question, in the sense of freedom I allow myself, which I sometimes encounter from the outside—when they do not agree to present something of mine, or when I curate an exhibition and the works in it are perceived as provocative—it’s kind of my own blindness. I don’t see things as provocative, as things that require courage. I really don’t feel brave in the world, and certainly not in the work.

Is the gray of the cover the gray area where your works reside—in-between good and evil, and black and white? That’s a very beautiful and heartening interpretation. The gray of the cover came from the thought of the archival report. It was important to me that it be a paperback book, with an everyday, practical appearance. I didn’t want the cachet of an artist’s book. On the contrary, I wanted an unglamorous book that would look a bit like a notebook. With Studio Gimel 2, we started from the idea of brown [institutional folders, and retreated to gray because the brown was too pronounced. Gray is also used to calibrate exposure in photography [for correct white balance]—what’s referred to as 18% gray [or middle gray] (a shade of gray that reflects 18% of the light that hits it)—and indeed, as you wrote—the center of the scale between black and white.

Let me take a moment to quote Gish Amit from the book: “An injustice that has not been redressed has a tendency to resurface and make its claim. We may recall the Freudian house, permanently inhabited by ghosts from the past, whose walls are never thick enough to prevent the return of the suppressed. However, injustice is not an object in the world. To correct it, one must first acknowledge it.

Memory, as Zygmunt Bauman noted in "From Vanquished to Victor" can "heal wounds or aggravate them, and past actions are not mistakes or errors in themselves, but only when they are narrated as such.” I’m having a hard time thinking of a more politically and uncompromising artist than you; every placement of an object and photograph empowers and sharpens the responsibility and guilt, but not only. It’s never dichotomous with you—there’s always something else above and below and alongside. I’m curious as to how you see it, in the context of what is today called “artivism?”

I, of course, agree with you that one of the reasons I create is related to the power of art to shoulder responsibility, and in that sense also my attempt to take on even if only some of the blame for the pile of injustices perpetrated in my name as an Israeli, as a consumer in the capitalist world, as a member of the middle class. The way in which it, that is art or I, the artist, does this is connected to the way it reveals latent mechanisms of power, the way it insists on seeing in spite of everything—as we mentioned earlier.

In this sense, I can put any thought-provoking, challenging art that opens an opportunity for the redistribution of reality under the umbrella of “artivism.” This is true whether it directly touches on political wounds, such as in Ella Littwitz’s wonderful exhibition A High Degree of Certainty, or simply allows for a new space of knowledge, a new way of looking at the world, as in the joint exhibition of Tamar Harpaz and Asaf Hazan Till I end my song; the kind that later brings you back to reality with new tools through which to look. And in the same breath, I want to say the opposite; that one can ask how much of what I’m saying here really has any substance. In other words, whether art is nothing but a cover, even a quite pleasant and soft cover for the injustices that I can’t and will never be able to rectify; whether in that sense it’s actually no more than an opportunity to escape responsibility.

What do you consider to be the book’s achievement? And how has it affected your work since it came out?

Most of all I think there’s something in a book that keeps living, as opposed to an exhibition that goes up and comes down terribly fast. The fact that people keep perusing it, that I give it to colleagues and new friends, that it’s a pulsating and independent body that is independent of time and place. That’s not a particular achievement but more of an ongoing effect. In addition, as I said at the beginning it allowed me to move to new areas of work, to a slightly different type of research.

A book’s title is like a secret. Does this title have any other hidden secrets?

There are secrets in the book, not necessarily in its title. It embraces more personal changes than it would seem, and perhaps even tells one or more biographical stories.

And what about teaching at Musrara? You’ve been teaching since 2015, would you like to speak about this experience in the context of your artistic practice?

I view teaching in general—not only at Musrara, but these days also at Kibbutzim College, and previously at Herzliya Gymnasium High School and in the now defunct Basis for Art and Culture—as an inherent part of both artistic practice and political action and thought. The raw encounter with people, the possibility of creating multicultural spaces of discourse, the junction with the kind of art I defined earlier, the kind that gives new tools through which to look at reality. In all of these, there’s a real sense of accomplishment, sometimes even more so than in the act of private creation itself. I hope that one day I will be able to write about some of the very interesting moments that happen in the classroom, about the conversations and encounters that occurred there, about how art can almost quite literally provide room for another political discourse.

Who did you secretly dedicate the book to and who would you want to have leaf through it?

The truth is that the book is always dedicated to someone else. Depending on who and what is moving at any given moment.

Our conversation is taking place just before you set up a new exhibition in chilly Norway. What’s on the agenda? Is there a link between it and Plunder?

Right! This exhibition in Norway is really exciting for me, even though it’s happening remotely. It will take place in a small space, about a 30-hour train ride north of Oslo, in a city called Bodø, which is located on a fjord. The space, called Atelier Nōua, sounds quite fascinating and is dedicated to contemporary photography, and to discourse on photography. There are three of us artists participating in the exhibition which is titled Power & Paper, including an artist I really like named Claire Strand. Unfortunately, the exhibition has been postponed for a year because of the coronavirus and I won’t be there to see it in person, but a rich and exciting online program is in the works. In the exhibition, I’ll present excerpts from the Looters project and excerpts from Abandoned Property.

These days I’m also participating in a group exhibition on the other side of the world, in Tenerife, the Canary Islands, where I already presented Looters, at the same time that the project was exhibited in Israel. In fact, both exhibitions opened on the same day. The current exhibition is a small show dedicated to our relationship with plants and how that has changed with the coronavirus. The curator is Gilberto Gonzalez whom I’ve worked with before, and we converse like old acquaintances despite the many miles that separate us.

What book should we add next to our library?

I’d love to recommend a book of poetry called Water Water by Alex Ben-Ari, with its layers upon layers of concealment and disclosure, of word and form, making it a kind of art object in its own right, a small and heartbreaking diamond. Although the book is out of print, I still recommend it and a conversation with the very wise Alex.

Where can readers get a copy of your book?

At HaMigdalor bookstore and at the new Magazin III bookstore, on Olei Zion Street in Jaffa.

Michal BarOr, born in 1984, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. She received a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem and an MFA from the Royal College of Art, London. BarOr explores the power inherent in turning objects into a historically and politically structured body of knowledge. In her works, she uses fragments of existing photographs, merging them with three-dimensional objects and texts to create an archival photographic installation. In 2015, she won the Israel Ministry of Culture Young Artist Award. As of 2020, she heads the “40-Something” program at the Photography Department of the Musrara School of Art in Jerusalem.

"I think of this book as a collection of meditations about the intricate relationship between the concept of “plunder” and the artistic artifact. With the Looters exhibition, I tried to remap my work, and I noticed that in hindsight one can identify a return, as if [I had been] possessed by the question of plunder—the question of the ownership of objects expropriated from a person, place or foreign body, and integrated into the fabric of the looter’s identity."

"I’m well aware of the political conditions that afford me—as a white woman and a Jew in a racist country—access to spaces that are more difficult for others to enter. The institution’s gatekeepers are more open to accepting me; they’re less suspicious of me."

"There are secrets in the book. It embraces more personal changes than it would seem, and perhaps even tells one or more biographical stories."