Paper and Scissors is your second artist's book. Your first book, My Rainy Day Book, is a homage to a children’s book that your great-grandmother, Anna Warburg, wrote and published in her native Sweden. Her books did very well at the time and were translated into German, Danish, English, and other languages. You work with the family legacy in your installations and in the current book. This time, dealing with family traditions is even more in material terms than before. Can you tell us a bit about how the book was realized?

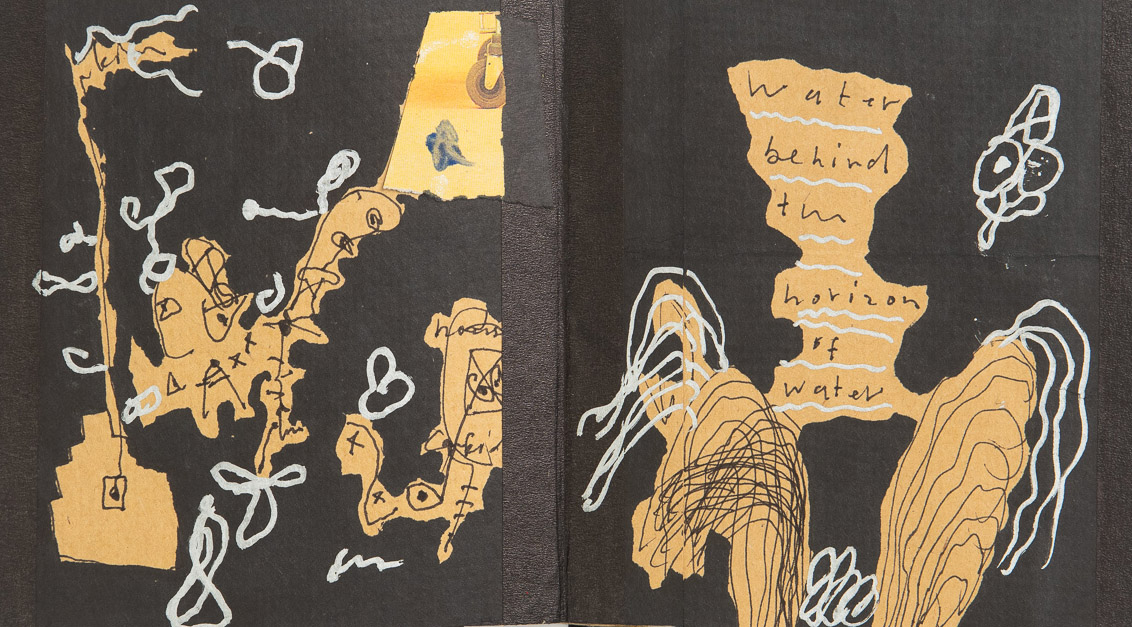

During Covid-19, I wanted to do something practical, something that’s not “art” per se. All of a sudden, I had a mania for handmade things, at a time when everyone had to reinvent what to do at home and to find educational tasks to keep the kids busy. I wanted to translate My Rainy Day Book into Hebrew. In the original Swedish, it’s called: “Vad Ska Vi Göra?” which literally means “What are we going to do today?” In the English translation, it was called My Rainy Day Book. I realized that translating directly from the original Swedish was impractical and that working with the English version was a better option. I used Google Translate to help compare the different versions and saw that I was interested in the gaps between the translations and how they reflected cultural differences. That’s also where the translation started getting messy.

I remembered that as a child, I would use parchment paper to copy illustrations and text from books or notebooks. I still do this when I need to relax. The action of copying someone’s handwriting generates a process of assimilation and identification; it’s like an actor reciting lines from a play. A performative, immersive act. Nowadays, copying is treated as a problem, but so many professions require copying as part of their learning processes; it’s part of the way you form a partnership with a craft, and with a work of art. So, the book was born out of the collision between these two actions, the translation and the copying.

The additional texts you chose to work with in Paper and Scissors were taken from family albums and Anna Warburg’s personal diaries. They exist in three “forms”: her German manuscript and the English and Hebrew translations. The texts become like a cipher, a secret code, or pieces of cloth sewn together.

In our family, stories always came in two languages, at least. Inside each album, or book, we would use Scotch tape to attach the other language’s translation beneath the original text or right over it. It became our custom, perhaps because Anna emigrated from Sweden to Germany, and after that, the entire family fled to Sweden and my late Grandmother Noni, who passed away a few months ago, immigrated to Israel after WWII and picked up Hebrew at a relatively advanced age.

My grandmother spoke German, Swedish, and English, but it was a bit too late for her to assimilate Hebrew as well. The books she had at home were in languages I could not read, so I needed her there to translate them for me out loud, or we would take on a translation project together. My grandmother would also write books for us on our birthdays; at first, she tried to do this in broken Hebrew, and after a while, she switched to English. The other grandchildren or I would sit with her and write the Hebrew translation down as she spoke. It was a translation project that had a sense of passing things on, of encapsulating family history and memories, but most important was how it was all told, the storytelling.

Apropos tradition, the curatorial texts in My Rainy Day Book tell us how Anna Warburg’s objective was to teach children how to do things, make gifts, do things on their own. It was an educational project directly related to the democratization of skills that would enable children from the lower classes to access artifacts of significant aesthetic value and experience independence. In your book the educational part is flipped, you ask your readers, most of whom are adults, to do a childlike act.

I realized that I’m continuing, as a grown woman and artist, to do what Anna taught kids to do in the book, and what my grandmother taught me, and I just got really good at it with the years.

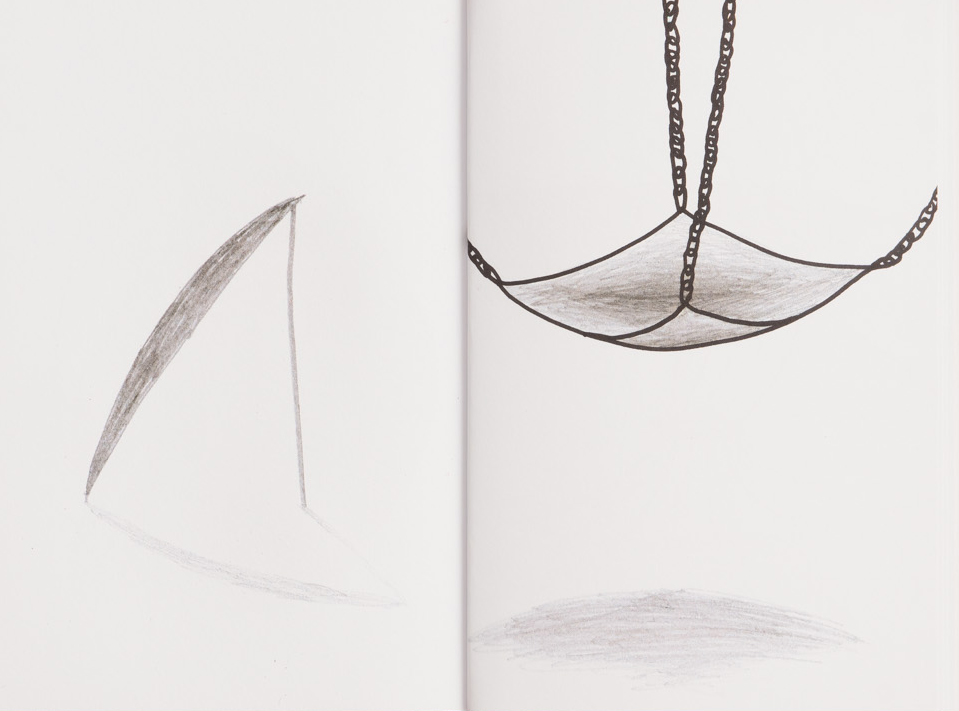

As an artist, I do Origami and paper cutting, and you could say that I’m trapped in this world. It’s like sacred texts for me in the sense that I can go back to them and copy from them, go back and cut, and every time discover something new about myself, both as a woman and an artist. This is also an action that alleviates longing. Artists have certain characteristics that are sometimes not very useful but are quite dominant. For example, the ability to imagine, to identify with something, and feel empathy. My grandmother kept very particular objects around her, objects that dated back to the family home in Hamburg, and she would talk about them as if they were connected to the people who used them. When she would tell something about Murmur Ellen, her Swedish grandmother, she would extend her hand and gesture towards the Swedish rocking chair. History lived with her. She would also cut actual books in ways that I do not dare to do myself. I Xerox the original and cut the Xerox.

One could say I am continuing the family educational project; the difference is that it has become “something” inside the sphere of art. I wonder if this is a betrayal of the tradition or a continuation of it.

I find the connection between analog film editing, splicing, and taping of celluloid to the editing you do through cutting visual and textual elements fascinating.

Yes, but why would anyone outside of the family take an interest in these texts? That’s a question I keep asking myself. For Paper and Scissors, I wanted at first to translate one chapter at a time, but instead, I found myself cutting and pasting, making collages. So to be productive, I took a chapter and cut it up with scissors. Now is a good time to reveal that the original My Rainy Day Book (Anna’s version, my great-grandmother) is an instruction manual for papercrafts. While re-reading it as a mature artist, I decided to go through all the tasks that kids were asked to perform. I found that my body automatically remembered all those instructions from my childhood. My grandmother had taught us to do all those things. The book is written in the first person; Anna speaking to the boys and girls. Suddenly I felt the text as a communication channel between us; she speaks and I listen, and I can also respond.

You’re showing me family albums straight out of the mid-18th century; the truth is I don’t really know what to do with myself here...

Yes, yes, there is a handwritten diary here, from the 18th century, belonging to Noni’s German grandmother, Charlotte Warburg, her father’s mother. And these are travel journals that Anna wrote to Noni when she was a child. Later on, I realized that part of the travel journal will become part of my book. For me to be able to read it, it went through its own journey: the journal was handwritten by Anna in German. A wonderful friend, the late Miryam (Thea) Paulene Kreutzbard, who knew my family from Hamburg, deciphered the manuscript for me. Another amazing family member, Maria Cristina Mills, translated it into English for me. I’ll read you an excerpt:

My upcoming exhibition at the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod is called “Forgetting Beautiful Things.”

Forgetfulness and memory are also present in how you “twist” the table of contents for the readers of your book. Leafing through it, it’s not entirely clear where each section can be found; one has to go page by page and decipher the writing to restore order while reading.

If you read the opposite text in Hebrew, it sounds like my Grandmother used to speak—Hebrew words with German grammar. I miss the way she used to talk. The way male pronouns became female when she named objects and people. It was also important to me that the book had a preface; like a house has an entrance hall. But I ended up being rude in the end because the preface comes after the first chapter, immediately followed by an epilogue. It’s a very universal preface that could have opened any book, in my opinion.

There is another sentence that I just have to quote, which I will translate freely from the German: “If you wish to travel, keep very quiet. Go at a steady pace, Don’t carry much. Get up early in the morning, And leave your worries at home.”

Anna is quoting a sentence that opened each and every “Beadeker,” a German brand of popular European travel guidebooks, written by Carl Beadeker, and still sold today, with practical advice on where to sleep, how to travel, and how to pack.

I’m just organizing things for my own sake here: this is Anna, your grandmother’s mother, who quoted the passage in her travel journal, for Noni, your grandmother. How did you find out that this is a quote?

Noni would tell me that this is something that her parents would say, but she didn't remember the context, like much of the advice she passed down to me. Every once in a while, there would be inconsistencies, sort of “holes” in the stories. I’m crazy about those. I only figured out the origin of the “familial” advice when I meticulously translated the travel journal. Apropos travel, according to our family lore, Noni’s father, Fritz Warburg, would travel everywhere with a suitcase full of books, even though he never actually read them. He just wanted them by his side. But they left their worries at home.

I do this too, not a suitcase, but much more than necessary.

Me too! I think I’m actually trying to protect myself from the journey. We get handed down such weird habits.

You also cut up photographs, which is another family habit. The act of cutting up Anna Warburg’s family album appears in the video work (“Paper and Scissors,” 2018), that was shown at the Warburg Haus in Hamburg, the historical seat of Aby Warburg, today the interdisciplinary forum for political iconography. One cannot miss the connection in how the photographs are arranged in her album and his monumental project.

The “Mnemosyme Atlas,”or in its full name: “Mnemosyme, a series of photos for the research of expressive pre-subjective values in the ancient world for the demonstration of a significant life in the European Renaissance,” is an immense intellectual work, most of which did not survive and was reconstructed only in the 1990s from photographs. Nowadays, Warburg is considered the person who laid the foundations for the multidisciplinary field of research known today as “visual culture.” I’ve noticed that you almost never mention this family connection in interviews. I can guess, but I’ll just go ahead and ask... why?

When I was a child, no one around me knew who Aby Warburg was. It took me time to realize that people know things about my family, things I had perceived as esoteric until a relatively advanced age. When I was a teenager, I hung a poster of Aby above my bed, hoping that his wisdom would seep down to me. I saw him as sort of a progenitor. But I always felt that I needed to create my own space, which would “justify” this connection to his work. What’s more, his story is very complicated, like that of the entire family and I always focused on the female side.

The Warburg family was actually matriarchal, but in the first half of the 20th century, it had five dominant brothers and two sisters who were almost shunned from memory. My grandmother did everything she could to hide the connection and was happy to change the family name. The album, Sommerhaus-Cutout, I worked with for the exhibition in Hamburg was organized by subject, similar to Aby’s Mnemosyne—the landscape, the sandbox, the walkways, the grass, etcetera. They both had similar sorting disruptions, and I have no doubt Anna was influenced by it.

When I began working, I looked at the album and asked what it wanted from me. My grandmother cut up half of the family albums she had in her possession. Perhaps this was a therapeutic act; she refused to hand them over in an orderly way and used their fragments to create new, crooked stories.

At some point, I asked her to find me the remnants of the festive album that Anna had made and promised that I would not judge her even if she had actually eaten parts of it. The fact that she was a princess in Hamburg did not turn out to be very useful in Israel’s Negev desert, where she eventually lived more than half of her life.

And talking about her German past was probably out of the question.

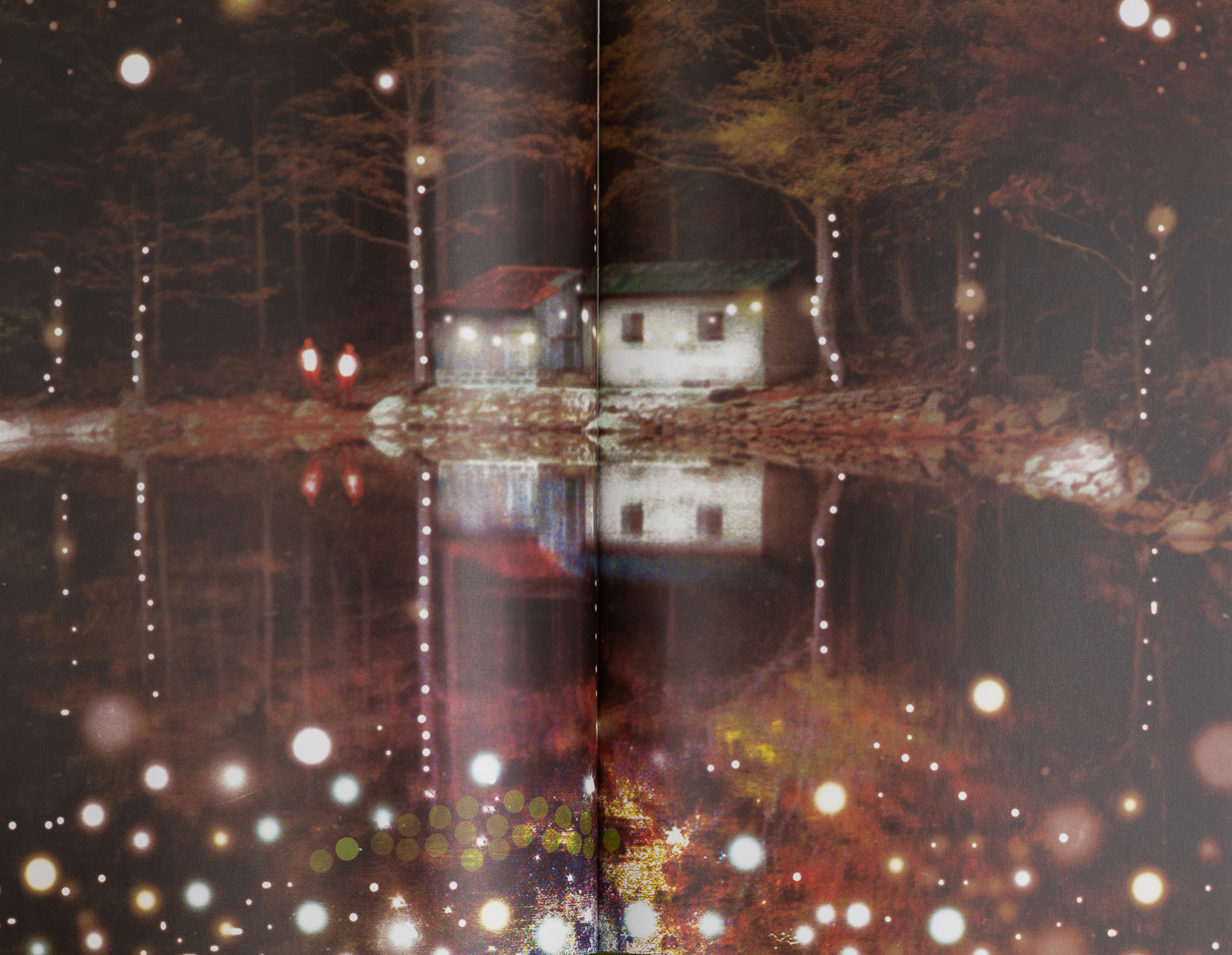

We talked a lot about the past in a certain, indirect way. She imparted to me a longing for places I had never visited. My grandmother never said “I miss Hamburg,” because in Israel in the 1950s it forbidden to say that you missed Germany That holds true for an entire generation that came from a world torn to pieces. The homeland she experienced doesn’t exist anymore. The house she remembered is gone. In her old age, the childhood memories sharpened and others blurred. In the last years, I half-jokingly suggested that we travel together to Hamburg, and she would not agree to it. She said she “just closes her eyes in order to be there.” My grandmother lived to be 99 and I was fortunate to be with her as an adult, and be cognizant of her legacy.

Being essentialist for a moment here, it’s interesting to see how the female and the male parts of the family complete one another. The women were engaged in progressive education through crafts, translation and writing the family history, and photography also. Warburg, representing the male side, busied himself with mythical aspects, historical and psychological, embodied in the political power of imagery. This even enabled him to predict the future, right?

Apropos women and men, in my grandmother’s stories, most men were awful. Regarding Aby, family mythology has him in possession of a real sixth sense and able to predict the future more than once. During work on the Mnemosyne Atlas, he would collect photos on a specific subject, place them on a blackboard, take photographs of them and using the photograph, see if the board works or not.

The board is a tool. If it doesn’t work, one can try again. After WWI, he decided to collect all of the photographs that appeared in several wartime publications. As far as we know, he predicted what would happen in Europe during the Second World War just by studying them. He was furious at the media for having exacerbated the state of political affairs and would send angry letters to the editorial boards of newspapers. He was already a well-established researcher. Following these insights, he went mad and wanted to kill his family himself, was committed to a psychiatric ward and luckily made it out of the crisis. He died at an advanced age before the beginning of WWII.

After he was released from the hospital, he planned the building where the Warburg Institute is housed today. A futuristic, elliptical library with a room for his boards, dumbwaiters and a pneumatic tube system for the books. The method of cataloguing and displaying he suggested was radical and poetic. It’s called “the good neighbor.” His idea was that the information I’m looking for isn’t found in the book I’m looking for, but in the book next to it, like in the song, “You can’t always get what you want, you get what you need.” He arranged the books by subject rather than alphabetically by author.

They were able to smuggle the entirety of his library to London before WWII, including the shelves and furniture and reestablish the institute there. Warburg Haus in Hamburg remained an empty shell. Apropos cutting, as part of his attempt to understand the war, he made his wife and kids cut up the newsprint photos of the war together with him. This is his only project that was totally lost. It’s interesting that the researchers at the Warburg Institute, who used images in their research before the computer age, would cut and paste as part of their day-to-day work. This brings me back to your question about the educational interest in my book, asking older people to cut and paste.

Yes, you ask people to take part in the research. You are issuing a second edition of the book and launching it in a new exhibition. What has been the reception so far? Has anyone actually dared to cut the book?

For the time being, there have been a few who said they have, but the truth is the sales are not done through me directly, but through the Sipur Pashut and HaMigdalor bookstores. So, I don’t really know. I wish they would!

Which book should we add to our library next?

Fichte, by Dana Yoeli. An artist book that is both beautiful and a travel journal connected to memories handed down from her grandfather. It’s perfect.

Hila Laviv (b. 1975), lives and works in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. She holds a BFA from the Beit Berl College, Faculty of the Arts, and an MFA from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem. Using archival materials and materials that characterize handicrafts, Laviv’s works deal with family mythologies and questions of reconstruction and rebuilding of disappearing worlds. She works in a number of mediums including video, collage and large-scale installations. In 2021, Laviv presented a solo exhibition at the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod.

"I remembered that as a child, I would use parchment paper to copy illustrations and text from books or notebooks. I still do this when I need to relax. The action of copying someone’s handwriting generates a process of assimilation and identification. It is a performative, immersive act. The book was born out of the collision between two actions, the translation, and the copying."

"The original My Rainy Day Book is an instruction manual for papercrafts. While re-reading it as a mature artist, I decided to go through all the tasks that kids were asked to perform. I found that my body automatically remembered all those instructions from my childhood."

"It was also important to me that the book had a preface; like a house has an entryway. But I ended up being rude in the end because the preface comes after the first chapter, immediately followed by an epilogue. It’s a very universal preface that could have opened any book, in my opinion."