How did your book come into the world?

I think that at a certain point in the work process, every artist thinks about making an artist's book. During Corona, I was cleaning up the basement and found a piece of paper from 1994 on which I had written things I wanted to achieve by 2004. There were some things I still have not done, but I also wrote there that I want to do an artist's book and produce an object that contained something that an exhibition couldn’t show. And this book has even deeper roots. It sums up 28 years of work. Work on the book began out of an amorphous passion, and at the same time, I had an inner sense of the steps required to make it. It reminds me that when I was 17, I wrote and illustrated a book of poetry. I brought it to the publishing house that published it as a finished product. I just knew how it was supposed to look.

What can a book do that an exhibition cannot?

I can pinpoint the exact moment when the desire to make a book began and first took shape. A curator asked me to send her texts that had been written about my works and when I told her that I didn’t actually have any she was surprised, and it was like an awakening. I had had 13 solo exhibitions and I realized it was time to put out a comprehensive book including significant essays.

I looked at my CV and remembered that in 2004 Galia Yahav curated an exhibition of my work at Avni Gallery. She called the exhibition “Hacombina,” a colloquialism that means a shady business deal, but also comes from the word "combine," and presented a “destructive” act of dismantling and reassembling complete series of works. I thought to myself that my book needed a similar editorial strategy. I wrote to Galia and asked if she would like to be the editor and she said yes. I think the texts in the book were the last things she wrote. Galia Yahav passed away in October 2016. I worked with her for about a year. Our collaborative thinking helped me understand and summarize the themes I had dealt with until its publication.

Can you elaborate?

Galia was very familiar with my works until the 2000s. She connected with them as a whole, and talked with me about creating seven chapters for the book; sections that would be keys for reading the works. She mapped out three main themes that became three chapters: Little Women, Landscape on a Platter, and Losing Your Mind. After those, she said she thought she was done. For me, it was important that the book also address aspects related to nature and biography. I asked the historian of photography Roi Boshi to write about Utopia Park, the last exhibition I had at Indie Gallery in Tel Aviv. The text “Touching Landscape” became the fourth chapter. I wrote the fifth chapter, “Photographed Evidence,” which responds to photos from my family album.

At that time, were you already talking about the object itself?

When Galia suggested seven chapters, we realized it would affect the book’s visibility. We talked about a product that was ripe and full of transitions and seepages. After she chose the corpus and after the written materials were edited, we arranged a meeting with the designer Avigail Reiner. But Galia didn’t show up, she was already very ill. I wanted to reach the finish with her, and it took me a while to realize that I was alone, that the decisions from now on were mine. There was a long period when we would have conversations in my head.

So the work actually continued with Avigail?

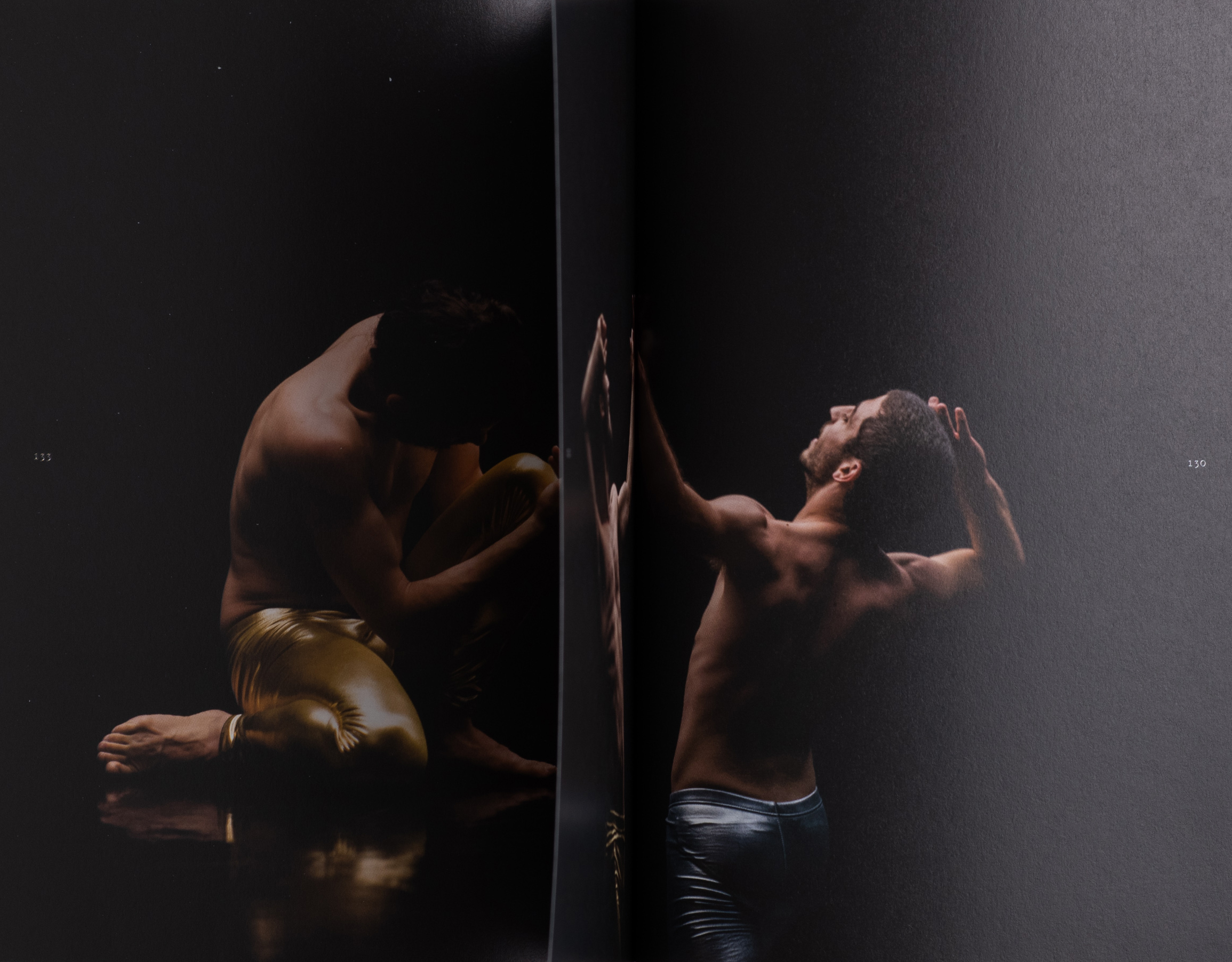

Yes. We realized that the book was constructed through two colors, which embody the realms of my wanderings as a photographer. The black, dark, deep places and the glittering; high places. My works exist on the scale between these two colors—black and gold. Offset printing is based on four primary colors: blue, magenta, yellow, and black. We put gold into the book as a fifth color.

Gold, which is a pure element in nature, is related in the book to solar energy. In terms of photography, light, and knowledge—it’s embodied in it in several ways. The thought of being able to give gold material aspects in the printing was very inspiring for me. On chrome paper, it has a glossy expression, and on synthetic paper, it’s dull and sinks on the page. My photography moves between times dealing with recollection, magic, and “witchcraft.” I feel we were able to use gold in a way that gives visual concretization to these themes.

And of course on the cover…

I dreamed of a hard cloth cover book with gold embossing. And it happened. Working with the designer was intensive. She knew how to embody my ideas in the material. At that time, my friend Ronit Shani, who is an artist, teacher, and photographer, moved to a new apartment and gave away part of her library. She said many of the books she gave away had narrow spines It’s funny, but maybe that was what influenced me to make a book with a thick spine as if that will ensure it a long shelf life.

The book also comes with an index of works. What’s the dialogue between them?

Until 2015, every action in my art was a reflection of processes in my life, so the chronological aspect is significant. The book attempts to produce a timeless and intertextual account at the same time. The index completes this by the fact that it contains a series from my student days at Midrasha Art College (1987) up to 2015. It also has a separate name, which completes my biographical story. I called it “Switzerland (maybe Canada).”

That’s a very poetic name for an index.

It is a poetic name with a dry factual kernel and a bit of shattering of a dream. I grew up in Nazareth Ilit and could see Mount Hermon from my bedroom window. Every year my parents would go to Switzerland and leave us girls at home. When I was little, I thought Mount Hermon was Switzerland. I really wanted to go there and they never took me. But we traveled a lot and my dad would photograph us against the background landscape. The other side of the coin is my mother, who, unlike my father who just wanted to travel, withdrew inside the house and using her amazing talents, turned it into a park of artificial landscapes.

My view of the landscape speaks to this complexity—as a background for a family photo, as a kind of second-hand experience, and as an artificial object. For me, the photo contains all these aspects. I don’t know if you remember, but there used to be photo albums with sticky paper and nylon dividers, and the cover photo would be of someplace. All of our vacation photos were kept in albums like these. I scanned the cover of one of the albums for the cover of the index. I was always so sure that the image on the cover of this album was of Switzerland—that sublime realm of childhood memory. But scanning the album revealed otherwise. I found the caption “Image Bank Canada” printed on it.

An index that also contains what eludes being pointed out?

It was important for me to show how technique gains momentum. Everything related to the presentation of landscape and straight photography is significant to me, in parallel with the practice of manipulated photography. Sometimes it’s difficult for me to distinguish between what was photographed and what was treated, so it was important for me to divulge the technique of each series.

And family photographs, which embody the fifth chapter of the book, aren’t in it.

Yes, I chose to write about photos from the family album I didn’t remember were taken. Through looking at them, I tried to recall my experience as a photographer and as the subject of the photograph. I hope that through reading these short texts, more images emerge that aren’t present in the book.

Many of your techniques are a type of re-framing of family-related themes, the relationship with the body; dealing with self and family healing.

According to my worldview, the photographic image has a life of its own. It can transform through sight and matter through time, place, and consciousness. Treating a family photo or a body photo is like touching the thing itself. Not in the therapeutic or ornamental sense, but as a kind of alchemy that occurs when a photograph meets action and material and reveals a secret. I feel that because of photography, I’m bringing knowledge from somewhere else. And yes, this practice can point to a wound and can also be healing.

How is this expressed in the book?

I live life and sometimes I don’t understand it. Then I do a photographic act, and miraculously the photograph precedes me and tells me where I am. All the photographic acts I did until 2015 have therapeutic aspects and that is in the book. I feel that it manages to embody the connection between the wounded place and the artistic tool. A kind of tikkun, repair, which Galia helped me understand and frame in historical-internal-artistic terms.

How does the image of the tree on the cover relate to this?

People asked me why I chose the image of the tree on the cover. I was told it looked military and reminiscent of the Golani brigade logo. The image of the tree has been with me for years. When my daughter was born 24 years ago, I received a bonsai tree as a gift, and after two months, it dried up. Later, I grew more bonsai trees and through caring for them, I understood the degree of synergy between therapist and patient.

They entered into my works as treated and photographed objects. A bonsai tree gets a lot of attention and minimal conditions so that it will remain small. It will forever embody the potential of the big tree that could have been. Among other things, I used it to talk about mother-daughter relationships. Designers say to leave the cover until the end, but I was preoccupied throughout the process with the question of “what will happen” outside the book.

The title of a book is like a secret. Will you let us in on it?

My father would take pictures of me facing the sun. Facing the light is an action that produces a seemingly damaged photo. It is also associated with nature, the supernatural, worship, temporary blindness, and empowerment. After the book came out I experienced a crisis, and friends said to me, “What did you think? You call the book that and think you won’t get burned?” And “facing the sun” is the exact opposite of how I lived as a child.

The house I grew up in was shrouded in secrets. In order to orient myself, I was constantly having to decode the messages. I wasn’t sure what was real and what I was imagining. For me the act of art puts things out in the open, enabling exposure, showing, and bringing into the light. Standing facing the sun is like standing in front of the truth and in front of the generative force that for me is akin to creation.

And what is it like after a book comes out?

It seems to me that anyone who publishes a book feels the gap between the process and the product. I stared at the printed book for days and days and couldn’t connect. I had become attached to the digital file viewed through a bright screen, and overnight it became an object in the world, and I need to make friends with it. In offset printing, each page is difficult to control in terms of color and darkness, and to my eyes, the end product seemed askew. The work in the printing house is noisy, fast, and almost violent. You are hurried, shouted at, joked with, and you have to flow.

A book that you worked on for two years is born out of this. Then comes the sensory experience, the smell, the leafing through it, and the touch of the paper. That’s how I experienced it. In the end, I fell in love. I’m already planning the next book and the one after that.

As I leafed through the book, I thought about the fact that a book is also a kind of home.

The image that comes to my mind is a box. I arrange objects and family photos in boxes. When I open them, they remind me of things I tend to forget and then transport them back into the present. The book closes a circle. I put a capsule of almost 30 years into it. When the book came out, I said goodbye to the work of the past. It took two years until I felt the move was complete, and I was embarking on a new path.

Is there a specific spread you would like to talk about?

The book has a spread depicting an image of a tree that is basically a self-portrait, in which my hands become two bonsai trees. Without planning, this spread is located right in the middle of the book. The seam is in it, like a kind of inverted spine. This is a photo I created especially for the cover of a catalog for a solo exhibition at the Museum of Israeli Art in Ramat Gan.

Another spread depicts an image I’m very attached to, and I also printed it on a canvas bag I put the book in. It’s called milim pninim, meaning every word is a pearl. It’s a treated photo of Esther Marcus, the wife of S.Y. Agnon, who would edit his writings. I wanted to give this humble woman a place and for her to envelop my book. I work with language editors and am amazed all the time at their ability to turn a written idea into a shining text.

Who would you want to leaf through your book?

I would invite a group of people from different fields, for observation and mutual discourse. I am interested in the encounter around issues of memory and vision.

Who did you dedicate the book to?

I dedicated the book to my teachers who empowered me: Simcha Shirman, Ronit Shani, Yigal Shem Tov and Avi Sabag. Each of them taught me about photography and vision and strengthened me as a person who wants and can influence the world. I also dedicated the book to my family and to my students who became artists in their own right.

What book should we add next to our library?

Frances Lebée-Nadav’s book General Allenby’s Showcase which was published in 2018. This is a charming, classic, and modest photography book about the shop windows of Allenby Street in Tel Aviv. And also News from the Underworld by Buki Greenberg, who defined himself as “an artist who came from nowhere,” published in 2007.

Where can readers buy a copy of your book?

Mainly through me, and you can find some copies in the Tel Aviv Museum store, at Tola’at Sfarim and at HaMigdalor bookstore, both in Tel Aviv.

Ayelet Hashar Cohen (born in Nazareth Elite, 1965), lives and creates in Tel Aviv-Yafo. A multidisciplinary artist who also teaches, writes, curates and accompanies artists. Studied at art seminary in Ramat Hasharon. For 15 years she ran the photography department at Mosrara school. Today, the director of the Mosrara school galleries Hashar Cohen examines in her works the seam between direct and manipulated photography, and between two and three dimensions. deals with landscape images and connections between internal and external space, personal and public, natural and artificial.