How did your book come into the world?

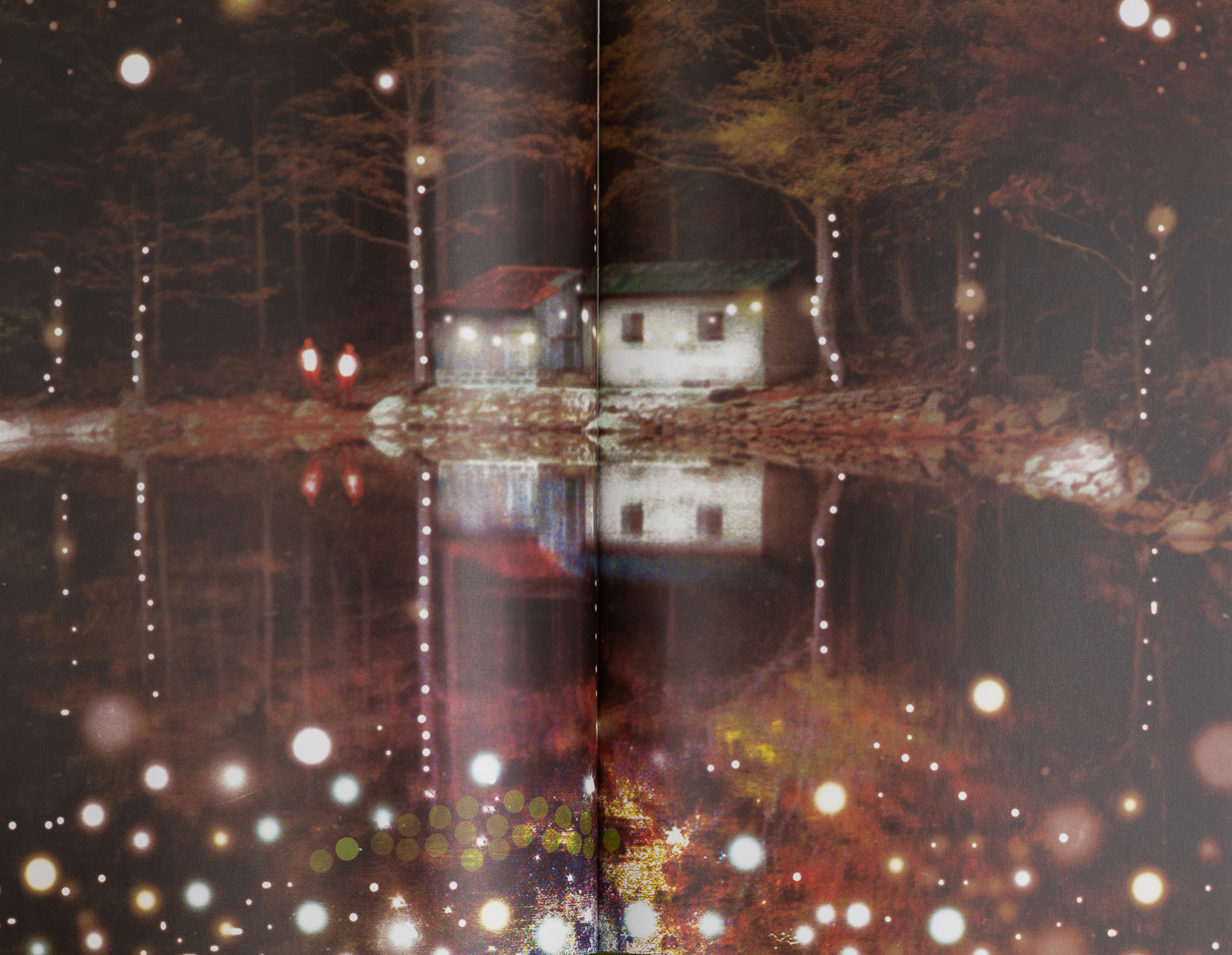

The starting point for my book was the documentation of the exhibition “Natural Worker,” which I presented in 2017 at HaKibbutz Gallery, that was beautifully and sensitively curated by Yael Keini. The exhibition dealt with the story of the Yemenite Jews of the Kinneret Farm, a group of Jewish immigrants who joined the Kinneret agricultural training farm on the shores of the Sea of Galilee in 1912. In 1930, they were forced to leave the farm and relocate elsewhere. In the exhibition, I was aiming for an installation that would invite the viewer to have a physical experience that would require them to move inside the space. The whole exhibition grappled with the relations between the text and the body, the history we carry in our bodies. I embarked on the creation of the book thinking I would create an object charged with the weight of a story and a visual experience.

What is a “natural worker”? Where did this name come from?

“Natural Worker” is actually a word pairing I took from an article from 1909 about Yemenite Jews that was published in HaZvi, a Hebrew-language newspaper published in Jerusalem from 1884 to 1914. It was written there that, “of the new Yemenites who have recently arrived, some 20 of them went to work the fields in the Rehovot colony. There is no doubt that at their core, these workers are more efficient… even more than our ideal and fresh workers, who are given the respect they are due. The Yemenite worker is the simple worker, the natural worker, who is capable of working in everything, without shame, without philosophy, and without poetry.”

You deal a lot with Mizrahi identity and history and with the colonial mindset of European Jews toward Mizrahi Jews who immigrated to Israel from Arab lands. One of your practices is working with the Hebrew language. You take words and make them into patterns, they become like tactile images. You manifest the idea of the interconnectedness of words and their context and meanings.

I use embroidery, which is a “traditional” handcraft. Sewing words means you give each word the time and space it deserves. This is heightened when I write out a sentence culled from letters written by the Yemenite community that lived in Kinneret Farm. They were people who were excluded from the history books, their story and their language are not preserved. The Yemenite Jews didn’t need Eliezer Ben Yehuda to rediscover the Hebrew language. They brought poetry with them to this place.

That’s one of the things that mattered most to me in working on my exhibition “Natural Worker,” and in working on the book. I wanted to underscore their connection to the language and this place. One of the ways I did that was by pointing at Rachel, the poet who immigrated to Palestine from Poland. She, too, did not get to have her story properly told. Those who will read the text in the book will understand more about the connection I see between them.

Speaking of the complex relation to language: The book is in three languages, Hebrew, Arabic and English. In today's political climate in Israel, this is a radical decision not to mention a significant financial addition to the cost of making the book. How did you decide to do a trilingual book and what did you learn in the process?

This was my direct response to the Nation-State Law, defining Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people and giving precedence to Hebrew over other languages spoken in the country, which was passed by the government in 2018, while I was working on the book. I was very angered and bothered by it. Despite the expense, I knew I had to do it. Creating a trilingual book is very complicated; all the meanings become so much more layered.

While I was working on the book, I had to make sure that the Arabic translation was working. So sometimes, when I would be on the train and would hear passengers nearby speaking Arabic, I would pull out my computer and show it to them. It was a way to determine how the texts would be accepted in spaces I’m not familiar with. Initially, people would read the title and not really get it, but after they got past the first paragraph, things would click for them. To me, that is the essence of a work of art. It’s not about offering someone a direct experience.

Nonetheless, my works are pretty straightforward, I don’t use sophisticated techniques, I create boats from paper or do simple embroidery. The repetition is what gives my work its power. My work process led me to decide not to include the names of the works in the book but rather to activate in readers this viewing experience that feels like a single sequence. This decision was also due to the fact that a lot of my works already contain texts, so it came about that each edited sequence of images begins with text works.

You make linen embroidered with text in gold, or fabrics that are stained with gold. Can you explain more about your use of these materials?

I chose linen because I’m attracted to the raw, physical, and earthy qualities of this fabric. I’m not a painter who paints on canvas. Painters who have been to my exhibition told me that they were unsettled by my use of linen. It’s a fabric that requires a lot of prep work, and it’s much more expensive than canvas. I treat it as a raw material, and place the colors directly on it, which is an untraditional approach. I use tons of fabric.

My choice of gold has to do in the simplest way with the image of royalty; gold is something sublime, although when used in popular culture it takes on a cheap appearance. This also takes me back to Jewish aesthetics, which are actually quite generic. If you take the Queen of England for example, you see that her clothes are embroidered with gold and velvet. If you read the Bible, particularly the descriptions of the construction of the Temple, you will find plenty of descriptions of gold, not to mention the story of the golden calf. These materials have a connection to something organic and primordial. As Jewish Israelis, we tend to think of our own local references, but these materials share universal origins and meanings.

You went for a similar effect with the cover of the book.

The cover image was clear to me long before I started the process of working on the book. We did many trials on fabrics of different densities, of different amounts of gold, until we settled on the right material for the binding process and the embossing of the text. I do have a dream to create a book that would be an object in and of itself, an empty book dipped in gold.

How did the process of turning the exhibition into a book evolve?

It took me three years. While working, I thought about adding earlier images I had created and older works, on the assumption that those would broaden the reading experience and provide more context for readers. For example, I added images from my final project at The School of Visual Theater in Jerusalem, which was titled: “28B Bezalel Street, #9.” That was an installation I had created inside an apartment I was living in at the time. In the image in the book, you can see a pile of all of the contents of the house heaped together: books, dishes, and clothing inside, next to, and on top of a closet.

In the other rooms, I had installed sculptural elements such as an origami boat, which I still have. I wanted to absolve readers from feeling that they have to figure out what I meant, in a way that was closer to the experience of looking at an exhibition. The book contains something of the genealogy of my preoccupation with the topics of home and environment, identity, family, and the body.

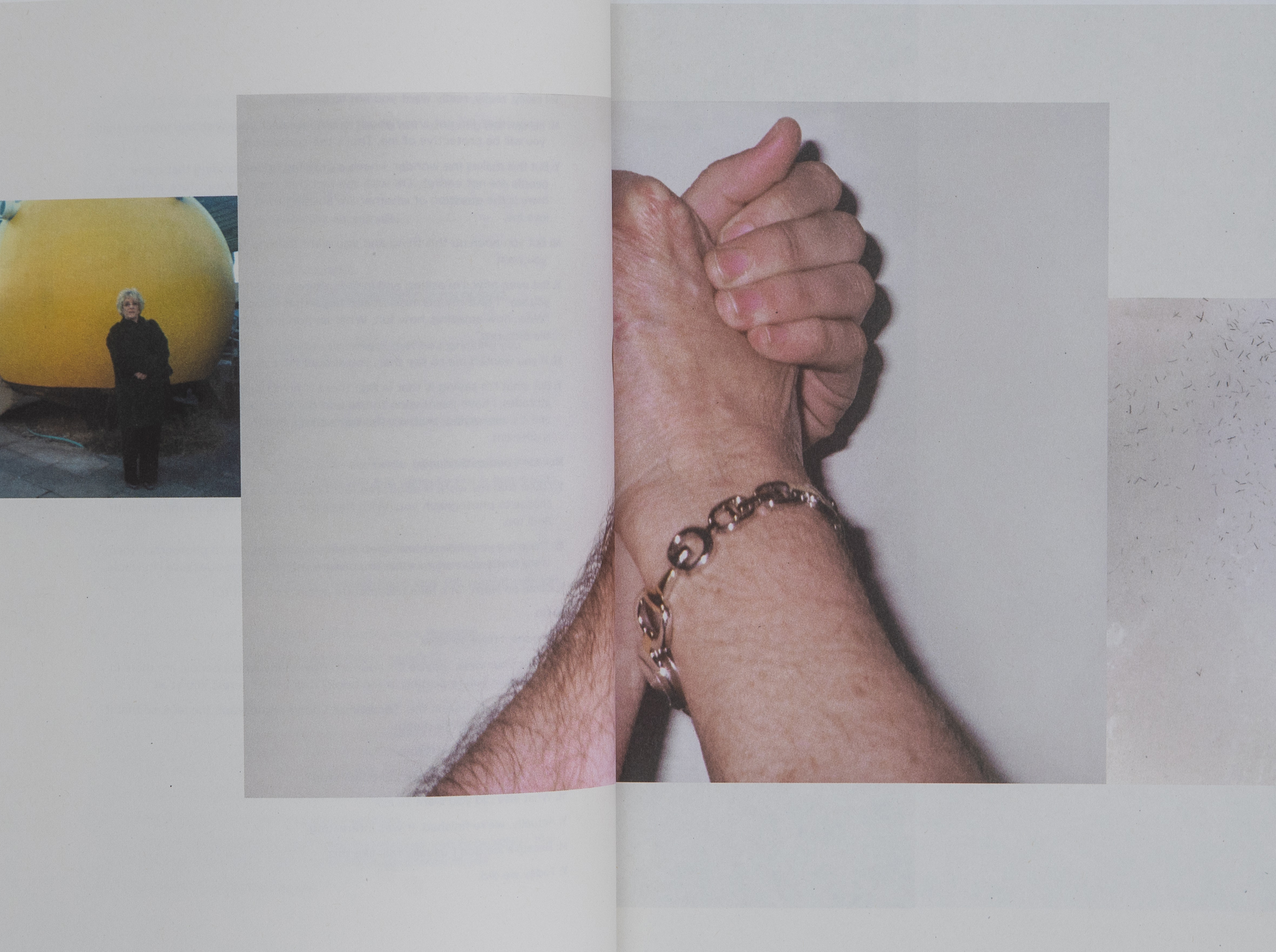

To this genealogy, you added to the book images from video works you made over the years that deal with the moving body. The different series seem to merge your parents, dancers, and portraits into a single flow of movement. I want to focus on one of these works—a video diptych you created about the Israeli singers Ofra Haza, known as "Israel's Madonna," and the Israeli cultural and transgender icon Dana International. It is a stunning piece. Can you tell us more about it?

When I lived in New York, I had time to write several columns for the Israeli news website Ynet, mostly about pop and culture. During the 2011 Eurovision Song Contest, I wrote a short column about Ofra Haza and Dana International, which I ended with the sentence: “Dana would have killed to become Ofra. And if Ofra had lived like Dana, she would be alive today.” This made me want to compare the two icons.

In Israel, Haza, of Yemenite descent, was an influential cultural figure who helped popularize Mizrahi music. She died in 2000, at 42, of AIDS-related pneumonia. Sharon Cohen, whose stage name is Dana International, is an Israeli pop singer, also with Yemenite roots. She won the 1998 Eurovision Song Contest, in which she represented Israel, with her hit “Diva.”

I started downloading videos from YouTube and juxtaposing them. I looked at them side by side. This raised many questions about visibility. Who taught these women to move their bodies like that? And what do we call “culture”? All of my video works contain a certain element of silencing. I created a video in which Israeli musician Yehuda Keisar can be seen playing the music of Israel’s national anthem, Hatikvah (“The Hope”) without singing the words.

In another video, dancers can be seen dancing to musical accompaniment that was edited, so that the liturgical rhythm they had originally danced to was removed and all that remained was the beat of a drum. In the case of Haza and International, when their voices were silenced, I could shift the focus to their bodies. Images from all of those videos found their way into the book.

What are your inspirations?

Joseph Dadoune, Anisa Ashkar, Elham Rokni, and James Baldwin.

If you’re bringing up Baldwin, I can’t help but refer to your installations of bookshelves. You have turned bookshelves into an artistic medium of their own.

On one hand, this very much fits my method of work. There is something about bookshelves that distills the essence of an idea, the poetics of the quotidian, something familiar but with a twist. Bookshelves are seemingly an innocent and practical way of organizing things, but every specific assortment of books is charged with a specific meaning—sometimes through a category determined by the titles of books, or by the names of the authors.

For example, I have a bookshelf titled: “Untitled – Mizrahi,” and it features names of authors of Mizrahi origin. What they all share in common is that they are all named either Yossi or Sami. Above them, I placed the Bible, kind of like a weight. Baldwin’s novellas are emotionally unsettling, and they reflect reality and awareness in a rare way. It’s very hard to make art that is both poetic and political at the same time. On my Baldwin shelf are six books by him that have accompanied me for a long time. I love Baldwin; he’s a king.

What a beautiful final note with which to cap off our talk.

Agreed. A book is an object that accompanies us. Throughout the period we read it, the book carries the index of the palm of our hand; the oils of our body are absorbed in the paper. Books deteriorate as we read them, as we go through our subjective experiences.

Who would you like to leaf through your book?

Anyone who is curious about it.

To whom did you dedicate the book?

My parents. Speaking of dedications, I still have the guest book from my graduation show. People wrote fascinating things there. For instance, my mother wrote: “When I stepped inside I saw the empty walls and felt fear over your maturity, the trajectory of your life, coupled with a joy that you were able to express it all in such an honest and real way.” Maybe it’s worthwhile to bring back this habit of including guest books in exhibitions.

Yes to that! What are we going to discover in your next book?

The process left me wanting more. It led me to direct my gaze backward, to examine a series of works I created in the past, and to try and bind them together in a way that gives them new meanings in the present. Right now I’m working with my father on reconstructing a memory from the house he grew up in.

What book should we add next to our library?

The artist book Toda Vida by Galia Gur Zeev.

Where can readers buy a copy of your book?

On Sternthal Books’ website, and soon, also on my website.

Leor Grady was born in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan in 1966; he lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel. Grady studied at Jerusalem’s School of Visual Theater and obtained a BFA at the SUNY Empire State College, New York, USA. Grady creates in various mediums, including sculpture, video art, and painting. In his craft, he uses everyday images and objects alongside traditional materials such as olive oil, gold and embroidery, with which he highlights his minimalistic research into national, cultural, queer, Mizrahi, Yemenite and traditional visual representations.

The Yemenite Jews didn’t need Eliezer Ben Yehuda to rediscover the Hebrew language. They brought poetry to this place with them. That’s one of the things that mattered most to me in working on my exhibition “Natural Worker,” and in working on the book. I wanted to underscore their connection to the language and this place.

'Natural Worker' is a word pairing I took out of an article about Yemenite Jews which was published in HaZvi, a Hebrew-language newspaper published in Jerusalem from 1884 to 1914, in which it said: “The Yemenite worker is the simple worker, the natural worker, who is capable of working in everything, without shame, without philosophy and without poetry.”