Sometimes it’s good to start from the present. You’ve been doing a lot of things with the book since it came out in 2018. How do you feel about it now? How has it affected you?

I love the book for the most part, which is strange. With most of the booklets I published, after they came out, there came a moment when I hated them, when I felt kind of angry at the project for being over. Because with the book, there was a different process, I’m still discovering things in it and my experience with it is still ongoing. It’s very rich, in terms of the period it describes, as well as the number of images and texts it contains. Lately, I had the chance to dive back into the materials in the context of the solo exhibition I’m presenting at the Haifa Museum as part of the “Women Make History” exhibition cluster.

After I received a lot of input about it, I looked at the materials again and tried to do something new with them. The book deals with the “I” and “versus” and relates to the discourse of power relations in photography. The things I’m working on in my studio today are different. Now, I’ve taken the people out of my work, and am mainly looking at spaces and objects. There are fewer snapshots, but I’m still very much collecting.

It’s time that we disclose that I edited the book with you. What did we actually do in the process in your perspective?

We started with an archive of about nine years of photographs that were taken in a variety of contexts and situations. It was challenging to organize all the materials we wanted to put in because it wasn’t a “project,” but rather images that were created out of impulse. There was no analytical process in terms of how most of the works were photographed.

And in you opinion, editing the book was analytical?

Yes. We were looking for a center that would gather the works, would create a structure or shape for them. I imagine it as a funnel. We tried to find the point of gravity things would flow into. That was difficult.

Were there any inspirations that helped you think about how you wanted the book to be?

At the time, I was very much influenced by Wolfgang Tillmans’s book Conor Donlon. The book consists of photographs in which Donlon appears in all sorts of situations. It helped me say okay, you can anchor parts of a book through characters. Organizing the chapters of our book according to key characters in my life was somewhat inspired by Tillmans.

When we sat down for the first editing session, I asked you what you wanted the book to accomplish out in the world.

That’s the most difficult question. Do you remember how I responded then?

We spoke about inducing discomfort in the viewer, challenging readers in terms of their homogeneous experience with the body. It seems to me that we were thinking about how a book can contain fragments without itself breaking apart.

What you just said is worded beautifully. I remember we spoke about the discomfort that surfaces around some of the photographs, and strangely it seems like that isn’t the experience that emerges from the book at all. In fact, something rather pleasant emerges from it. Even though it has flawed edits and design moves that may be considered radical. People give in to these contradictions. Something about the intimacy created in them feels somehow complete. I’m not sure what to say, I just noticed it now.

In my opinion, the book looks directly into some of the ways in which we sin against each other. It almost lists them. These aren’t big sins, but by-products of the journey of life. Many of the photographs seek to see things in a non-hierarchical way, to produce equality of the gaze: objects, landscape, (wo)men/people; to reflect on our place as (wo)men/people in the face of whatever appears before us.

How did you finally come up with the title?

Miranda July is a great inspiration for how to name things. The titles of her projects are like little poems. I try to create a similar feeling in my projects. That they’ll contain a broad emotional dimension, but also a personal one. An almost obtuse text that addresses the specific; that is each one of us. It’s fun that I can reference a well-known artist and not just any anonymous young creator.

Because you’re mainly influenced by young creators?

Because my references are usually contemporary ones, someone I have an artistic crush on, and also, because I don’t really remember the history. I think it’s called ADD. But, I can also say some things about the title of the book itself. Beyond the laughs. Should I?

Definitely.

As you know, there were many considerations. When we initially thought of “Dis/comfort,” it wasn’t just right for me. As we progressed through the process and the direction of the conversations with the people photographed (my mother, Nitza, Andy) began to take shape, the preoccupation with the power relations between us became clear. At the same time, our team realized that the preoccupation is with the subject-object relationship.

Around this time, the name “Doing Right By You” came up, which unfortunately can’t be translated into Hebrew in a way that isn’t fussy or that doesn’t simplify the idea of doing you justice or acting fairly with you. Of course, translating it into Hebrew would genderize the reference in the text, and impair the personal appeal generated by the title. Would you like to add anything?

Yes. We also had “Authentication Points,” as a working title, and we were excited by the fact that it was a term taken from army navigation drills that allow for situating yourself in space. Because of your preoccupation with the relationship between body and territory, it felt spot-on.

And it emphasized the connection between photography and identification, and the way in which your photographs seek to showcase, and at the same time complicate the identification process, and also underscore the confrontational aspect of the authentication process. So, the ethical spectrum of the book basically went from discomfort, through identification, and arrived at Doing Right By You. What do you think about the texts in the book in regard to this process?

It’s a question of whether people actually read the interviews when they first leafed through it. It seems to me that the texts are not as significant in the viewing experience. Perhaps above all, they helped us think about the editing, as they lent legitimacy to the photographs and the appearance of the archive. From my perspective, it was impossible to work without them because they actualize the voices of those photographed in the book.

Is there anything you would do differently today?

Maybe the interview with me could have been a little different. It’s a challenge for me to talk about things as I’m articulating them and before there is time for things to sink in. The making process was difficult for me. I’d love to feel relaxed and enjoy it more.

What is the book’s greatest achievement?

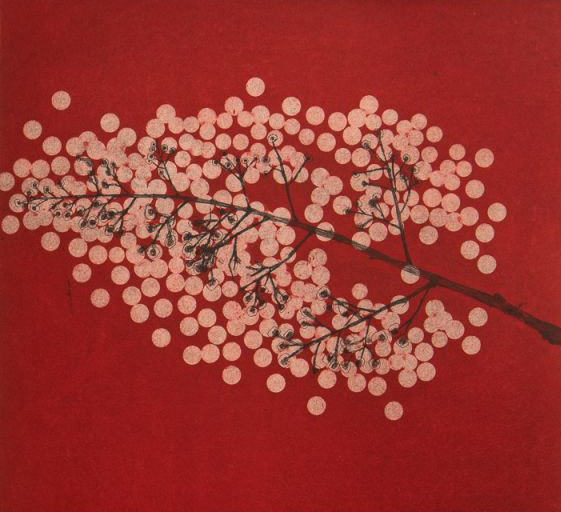

Perhaps the shade of pink on the cover that was created by mixing the shades during the printing. It makes me happy that the book participated in several book fairs like In Print in Jerusalem, the Chicago Art Book Fair, and the Istanbul Photo Book Fair, and also was one of 20 books on display at the MOPLA Photo Book Exhibition in Los Angeles. In addition, on a personal level, the book manages to complete a chapter in my practice, which is very exciting for me.

How long did it take to make?

Two-and-a-half, three years. The process revolved around the submission to the Israel Lottery for Culture and the Arts. At the same time, Sivan Rajuan Shtang gave me a real push with the text she wrote for the submission. Later on, I worked with Studio Gimel2, who have known me and my work for years. When you joined the team, things really started to get moving.

I’d be happy if you could elaborate some more about Sivan’s article (“The Lonely Torso: Queer Bodies, Territories and Nationalism in the Photographs of Yael Meiry”)?

The queer and local framing that Sivan made is very significant to me. She managed to connect my preoccupation with localism to Zionist history in a way that wasn’t clear to me before. It pushed me to keep working. To be more precise about my position. I really hope people read the article.

What did you learn about bookmaking that everyone should know?

That it was very expensive. I had no idea that producing a book is such a costly process. I also learned a lot about printing and offset printing in particular, working with Dana Gez at the printing house was very instructive.

Who would you like to have leaf through the book?

Wow. The question is basically who I would like to meet and speak with about art. Somehow, the first name that comes to mind is Tillmans. Do you know Collier Shore? She does studio photography. I’d be happy to meet her for a beer. Who would you like to have seen the book?

Jess T. Dugan, I guess.

Yes for sure. Also David Adika comes to my mind.

Who did you actually dedicate (or would you dedicate) the book to?

It’s a long list. I dedicated it to my parents, to Nitza, my partner, to Andy, to everyone who, or parts of them, appear in the book, to you, to Sivan. I also dedicated it to everyone who was involved in my life and in the making of the book.

Making a book is like…

It is like having an orgy, or wait maybe better, it's like getting married. It’s basically an opportunity to go wild with a ton of substances but then wake up with them every morning for the rest of your life.

What book should we add next to our library?

Michal Baror with The Book of Plunder, and Liat Elbling. I would love for Ronit Porat to make a book. Tell her. And besides, for more women to make books.

Where can readers get a copy?

On my website, and at HaMigdalor bookstore.

Yael Meiry (b. 1982) lives and creates between Tel Aviv-Yafo and Kiryat Tivon. They studied at Camera Obscura in Tel Aviv, Minshar School of Art, and Hamidrasha School of Art at Beit Berl College. Reflecting through photography and installations on landscape and body as territories, they deal with the queer body as a presence that signifies social, political, and cultural consequence. They received the 2018/2019 ARTiq Proud Art Award. In 2020, they staged a solo exhibition at the Haifa Museum.