How does a book come into the world?

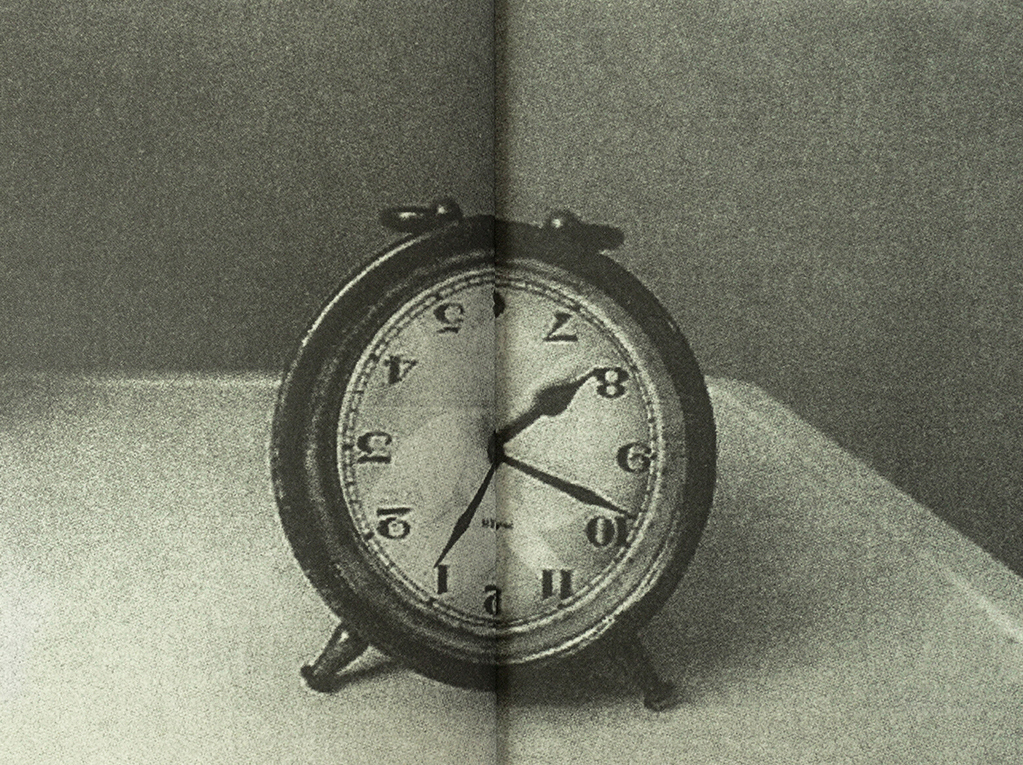

I’ll start with “what it is”—this project. It’s a body of work called Light, Time, which I’ve been engaged in for four years already. At its core is a very simple act: I shoot long exposures of the sun, from one hour to a whole day, with medium format film cameras and a very dark ND filter. The camera is mounted on a tripod throughout the entire shot. Meanwhile, the earth moves a bit, so what you see in the final result is the relative movement of the sun, which leaves behind a bright streak in the sky. The length of the streak is determined by the length of the exposure. In the final shot, the sun is seen in motion, and all of the other elements are static. I insert urban hints of specific places.

For example, I returned to Beersheba, the city where I was born, and photographed the edge of Danny Karavan’s monument to the Negev Brigade, as well as other places that have symbolic meaning, and that encapsulate time for me. I remember them from the age of two or three. They are static and only the sun keeps moving. My motivation in photography is really to capture time. Not a hundredth of a second, not half a second. An entire hour. A whole day. Trying to hold it, without letting go. The project contains all of the morbidity of a preoccupation with time, anxiety of death. That’s what it is.

Why did the project turn into the book In These Times? Why now?

The first lockdown of Covid-19 was a trigger to turn the project into something accessible. You want to be doing something, but the quarantine confines you to the end of your street or your rooftop. And I really was on the roof on most of the days of the lockdown from sunrise to sunset, photographing nonstop. You have to understand that out of each day like that you end up with only two or three photographs. Let’s say I travel from Tel Aviv to Beersheba, stand out in the sun all day, and sometimes the photos I come back with aren’t good enough. That’s part of the deal.

And during the coronavirus, on the one hand I created a lot of new images, and on the other hand, the usual art spaces were closed and a lot of exhibitions were canceled. I wanted to present my work, and I wanted something I could do myself, something completely DIY. I wanted to be able to give people my art in a physical manner, not mediated by phone or computer screen, or a gallery space. So one could say that without the coronavirus, this book wouldn’t exist at the moment, and I’m happy that despite the difficulties of these times, the book came out.

This calls for a connection between all this darkness that’s in the book and the plague.

There’s a quote by the Israeli writer Hanoch Levin that says all of it for me in a few lines:

“In the meantime, the days will pass, the sun

will rise and set, and we won’t feel it.

And in another year we will say:

‘What, a year already?’

And other such nonsense.

And we’ll laugh merrily as if

The days go by, not us.”

And yes, I wanted a book that would be an object in its own right, something gripping and daunting. I wanted to hold a black hole in my hand, the kind you could accidentally be sucked into, that could burn and cut you. One that’s a little too big, has too many frames. There was a previous mockup that was more polite, a sort of catalogue of works that didn’t contain the intensity from which I started the project. The paper I chose is reminiscent of newspaper, and I decided not to varnish it, so that each copy would turn yellow differently, so that its black ink would smear on the fingers, so that it would engender a physical experience of time for each reader. For me, a book that’s an object is a sequence that activates you, that’s irresistible.

The book actually has two sequences because one can leaf through it from both sides. It produces a sense of disorientation at first, and then one begins to try to understand the narrative—is there one actually?

Yair Barak relates to this in his text "Chariots of Black Horses" that appears on both sides of the cover. He writes: “A minor photograph between a moment and forever.” In traditional photography, there’s a decision, but this is the sun, how can you decide on it? It’s time, and what can I do in the face of time? But yes, there’s an evolving narrative here, and I prefer to keep it hidden. Mostly, I can say that the book starts with elements that are relatively recognizable, and slowly slides into the implied, to the edges, and then the frames begin to fall apart. The heating up of the camera while shooting sometimes cooks the film, which results in color distortions, insane losses, which I can’t anticipate. But yes, there’s some kind of beginning, journey, end.

In other words, the act of decomposition is constantly present; the dissolution of space and the stretching of time, and the breakdown of the medium.

I think about it in terms of abstract and figurative photography. This book is the most figurative work I can produce. Everything else in my portfolio up until now, fell under the definition of “stains,” pretty much. When I suddenly photograph something that can be identified, I pay for it in blood. The deeper I dive, the more my photography falls apart.

I’m listening to you and thinking of the photographs of Dalia Amotz and the title of the catalogue that Sarah Breitberg Semel edited for her after her death, Knowing the Black Land, On the Road to the Fields of Light. Dalia turned her gaze toward the earth; you turn yours to the sky, and both of you to the sun.

Look, it’s amazing you say that because a few years ago I was looking for who my “parents” are, artistically speaking, and after sitting in the library and leafing through a lot of books, I decided I was the illegitimate son of Dalia Amotz and the sculptor Ezra Orion. Anyone who knows Dalia, needs no further explanation. These are precisely the things that interest me. This place. This sun. Dalia created a photograph that does not try to “show something,” or convey information, but rather talks about feelings. Knowing and not knowing at the same time. Meeting her instantly changed the way I understood photography. The way she rearranged elements. Not to show, but to move the earth. I understood from Dalia that it’s possible to think that way.

Apropos of “moving” the earth, Ezra “moved” mountains.

Yes, Ezra was an officer in the IDF's commando; he was discharged with the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Golani Brigade after serving in the Six Day War, the War of Attrition, and the Yom Kippur War. Later in his art, he’d move mountains in the desert from place to place, or travel to the Himalayas, to the Annapurna ridge, where he built stairs that ascend to heaven. One of the most megalomaniacal projects he planned is called Cathedrals of Light. He wanted to launch laser beams into space—and from the moment they launch, they begin to sail in space. This was a completely conceptual project because it can’t be seen. In hindsight, I realized that if his project could be seen, it would look a bit like Light, Time, streaks of light moving in a dark space, and that my frames would look like the simulations he made for his project.

Talking about preoccupation with the time imprinted in the photo, it’s impossible not to talk about Hiroshi Sugimoto. In general, you seem to have a thing for Japan, because the copy we’re looking at now, number 53 of 365 copies, is signed by you in Hebrew and Japanese.

Yes. The 365 copies are an equivocation, and the signature is an homage to my love for Japan. In my opinion, everyone in the world must go there at least once. In one of my exhibitions, someone told me about a Japanese photographer, Yamazaki Hiroshi, who used a technique similar to mine. I researched him in Tokyo, and you see a whole different aesthetics in the photographs. He’s Japanese and the sun there is different. He’s looking for Zen, there’s always a river, sea, or some cherry blossom in the frame. I have dust, heat, urban scenery, and intensity.

Being a native of the southern city of Beersheba—it’s specific light that stays with you all your life. In Beersheba, for me, it’s enough to photograph the sky. It’s the practice that gave birth to this book. Can I do something here that Sugimoto will appreciate? I hope so. I'm trying to maintain a tension between wonder and violence that is unfortunately inherent in the place I work in. A place in which there is also much less respect for and engagement with nature, and that reflects deeply in images and art. You’re nodding like a psychologist, it’s a bit stressful.

Ha ha ha. Yes. It’s exciting how the biographical, the conceptual, the material, and the local-historical merge together in your book. What’s it like to edit, design, choose paper—that is, to basically do everything yourself?

I started by taking a huge folder and playing with possible arrangements. Most of my uncertainties related to the format, rather than the sequence. I knew what I didn’t want, but it was hard for me to understand what I did. In the end, what helped me was actually the budgetary constraints. I didn’t receive funding for the book and spending NIS 40,000 on printing was out of the question. But I decided I’d publish it anyway and preserve the essence by more modest means. I sent the project to Yair Barak, and he sent me back such a generous text with a deep understanding of the project. I translated it into English, and then I tried to figure out how I could combine Hebrew and English in a way that is true to the content, in a way that doesn’t interfere with the work of the photograph. Then the idea came up of designing it on both sides like the front page of a newspaper.

This connects to the book’s title, The Times, which of course references Time Magazine, one of the first magazines to feature photo essays, and also the work of the Yes Men who made their own edition of The New York Times in which they wrote the news they wanted to read.

It also references music, and all the millions of songs that deal with the passage of time. And music, which exists in time. The second title I thought of was Strings, which relates to string theory, the physical theory about particles being in a sequence, meaning simultaneously in all the places where they could potentially be. Like wires in space. But as soon as the title The Times came, I realized that it’s also a title that relates to the content itself, and also solves the dilemma regarding format: I publish a newspaper that reports what happened yesterday, the sun shone, and the sun also shone the day before yesterday.

It’s like the joke about yesterday’s newspapers that you can use to wrap fish. And what’s beautiful about the paper is that it has a design grid, it has a characteristic form. At that moment it was clear to me that the whole text will be on the outside, on the outer spread, and not be a single word inside. That way, the book functions like a kind of a trap.

Is it also a sad reflection on the relevance of art nowadays?

Yes, that’s there too. When you stay with a project for so long, it takes on a multiplicity of motivations and possible reading forms; it’s all here, including the wear and tear of the thin paper. It is intentionally meant for one-time consumption. I wanted a sense of a photocopied fanzine, of making a statement. The insistence on the type of paper caused a delay of several months in the printing, because the shipment of the paper I wanted, “Dalum,” got stuck due to the coronavirus, so I waited. It’s a thin matte paper, which holds shades of black beautifully. I offset printed the book, and the printing house went nuts when I asked them not to varnish. This was scandalous as far as they were concerned. But A.R Printing Ltd. prints lots of artist’s books, and they’re already accustomed to all these strange requests—nothing surprises them.

How did you decide on the size?

When I show this project in a gallery space, the prints can reach 2x2 meters. Size matters. I want the viewer to be swallowed up inside this black cube. So here too, I wanted it to be a bit too big to hold, like old-fashioned newspapers. By the way, for the book’s distribution, I initially thought I’d roll a copy with a rubber band for whoever ordered it and throw the book into their stairwell in the early morning.

Incidentally, I saw a video of a burning camera on your website. Is it considered part of the project?

Right. I made the video for the Master’s graduation exhibition at Hamidrasha, which was held at Hamidrasha Gallery at Hayarkon 19. I wanted to show the photographer’s temporality and nothingness, the surrender of the camera, to offer it as a sacrifice to the sun god. So I set a lot of cameras on fire, some on the roof, some in the Negev, some I set fire to, some burned on their own. That’s what I presented at the end, and it’s part of this body of work.

What did you learn about bookmaking?

The most important thing is to make physical mockups and hold the book in your hand. Make as many mockups as possible; there’s no substitute. That’s the only way to assess whether the design works, whether it conveys the desired feeling.

What book should we add next to our library?

Gustavo Sgorsky. He has a few books printed in conventional offset, but also handmade booklets that he occasionally releases on a specific topic, and I really like them.

Where can readers get a copy of your book?

Bezalel Ben-Chaim was born in Be’er Sheva, and lives and works in Tel Aviv-Jaffa. He holds a BDes from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, and an MFA from Hamidrasha School of Art, at Beit Berl College. By way of still photography, video works and printmaking, Ben-Chaim explores time and the disintegration and stretching of borders of the medium and reality. In 2021, he staged a solo exhibition at Binyamin Gallery in Tel Aviv.

" I wanted a book that would be an object in its own right, something gripping and daunting. I wanted to hold a black hole in my hand, the kind you could accidentally be sucked into, that could burn and cut you."

"The name also solves the dilemma regarding format: I publish a newspaper that reports what happened yesterday, the sun shone, and the sun also shone the day before yesterday. It’s like the joke about yesterday’s newspapers, that you can use them to wrap fish."