Vasarely Material Archives was published following your stay at Fondation Vasarely, a museum designed and built by the artist Victor Vasarely in Aix-en-Provence, France. In the book, which you initially did not present during your exhibition there, includes a single sentence: “Photographic interventions realized between 2017 and 2018 using materials kept in the Fondation Vasarely archives.” It sounds like there’s something of an untold story here.

Yes, it is quite a story. Where to start? First, let me just say that I don’t feel like it’s an artist’s book pur sang, even though I might have made certain decisions along the way that suggest otherwise. But we’ll get to that later. To explain, I think I first need to elaborate on my experience in France.

Let’s hear it!

I was invited to spend some time in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France, where Paul Cézanne lived and worked. I was allowed to work in his studio and make use of it as if it was mine, and this was really special. I am very influenced by Cézanne, his scrupulous manner of working, the way he looked at objects, and the subjects he chose to study repeatedly, like the Montagne Saint-Victoire, and of course “proto-Cubism” that developed in obvious relation to his work. Also located in this little town, which is a kind of “petit” Paris, is the Vasarely museum—Vasarely was the father of Op Art—which opened in 1975. Victor Vasarely objected to the flattening in painting, just when contemporary abstract art celebrated it. He argued that two dimensional, flat surfaces are non-existent in nature, and therefore for a work of art to include “mimesis,” namely the imitation of nature, it needed to encompass a dimension of illusion. In other words; the painting was urged and “invited back into nature” on the condition that it contained the illusion of depth.

When I arrived at the museum, I met Pierre, Vasarely’s grandson, whose father Yvaral was a significant artist in his own right. The museum looks a bit like a spaceship, and is located in the peripheral landscape of the St. Victoire, the mountain ridge Cézanne had painted repeatedly. By the way, a new museum with about 1,500 works by Picasso is planned to open in Aix-en-Provence. But that’s yet another story. Obviously, Vasarely didn’t just happen to choose this specific location.

You wandered through the history of modernism in Western art, and more specifically in France.

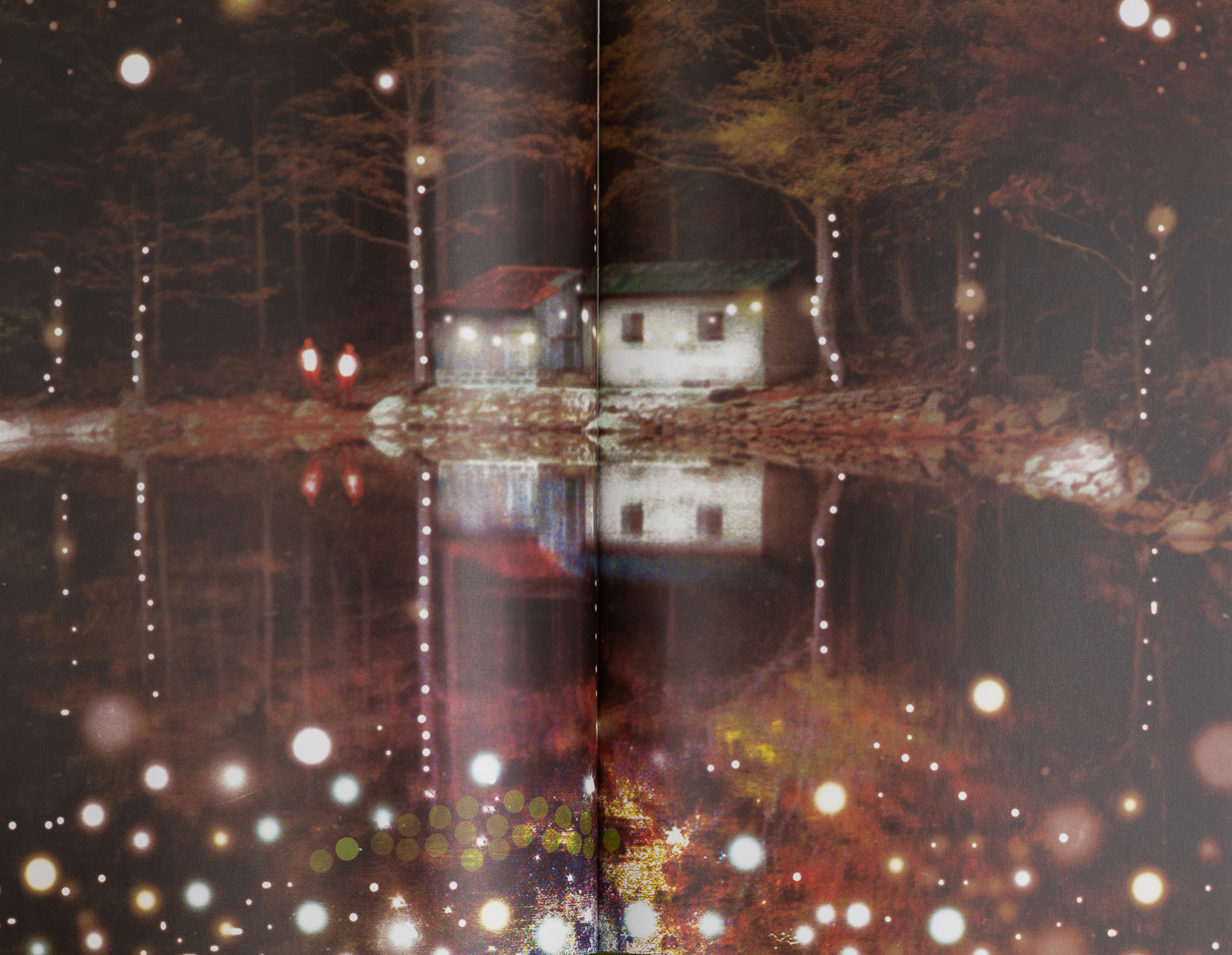

Yes, I explore Western visual culture as an artist who photographs. It was quite amusing because when I met Pierre Vasarely, I showed him my work, and he thought I was an architect. Thanks to this little misunderstanding, I received a full two-day tour of the entire museum and its spaces. This included the apartments that Vasarely had designed for himself and his wife, which is where I eventually ended up living for the duration of the project. About two hundred meters all around the museum, there’s nothing but barren land. Inside it is very dark, a bit like Stanley Kubrick’s haunted hotel. It was like a “night at the museum,” a night that did not end. The windows are made of darkened glass that makes it impossible to look in during the day, and out when it’s dark outside. The whole museum is built in the shape of a huge hive, which makes you lose your sense of direction—a true modernist maze.

The manager of the collection, Pascale, who is an art restorer by training, told me about the major renovation of both the building and the collection that was being planned. And indeed, during the tour that I was given, it seemed that some of the works were in dire condition, and desperately in need of restoration. I asked how they were going accomplish that, and she explained that there was a storage room with materials that Vasarely had left. I asked to see it and the moment the door to this room opened was the moment the project was born.

What did you find there?

A room filled with boxes. Vasarely had produced works in various dimensions and from different materials: glass mosaics, aluminum, painted cardboard, clay tiles and colored papers among other things. He would make huge enlargements and prints from his paintings. You could say he was “Pop” before the invention of “Pop art.” He also altered the materiality of a chosen design so that for instance a work on paper would become a huge tapestry. In the room, there were lots of boxes containing colorful tiles and papers. I proposed to work with this collection of materials, and to my astonishment, I was invited to stay at the apartment in the museum, was given the keys, and wished “bon courage,” good luck.

How stressful.

Definitely. I started by studying what was there, which works the materials belonged to. It was important for me to understand which of the materials were “spares”—those that were exempted from being used—and which were “original materials”—meaning those that could be used in the restoration of the existing works. I realized that I was busy building an archive that eventually might disappear.

A temporary archive.

Yes. I laid out all the materials and arranged them according to color. I gave each one its own definition, and photographed 900 separate pieces. Initially, I racked my brain on how to even start to photograph all those different elements. For instance, there are 200 rhombus shaped tiles. Vasarely had used those to cover his outdoor sculptures; they’re very heavy. First, I needed to clean them, and move them from the storage room to the apartment that also functioned as my work studio. You need to use special materials to clean them, and then they take on a beautiful brilliance that then needs to be neutralized with lighting for the photograph. Then there were silkscreens in almost 200 shades; several hundred colored papers from which he had made his collages. I began with the idea of creating an index of each material, but as the photographic action, or photographic intervention progressed, I realized that what I was actually trying to discover was the inner intention or will within the material.

What does the “material’s will” mean?

This is a situation of “critique” for me. Vasarely had shaped his sculptures out of elements made from all sorts of materials. What I was doing was connecting them and building something different from those same parts. I believe, perhaps like the painter or sculptor, that color can invite a certain choice to be made, and the material conditions the type of object. I tried to create organic shapes with the geometric parts available to me, and by that to refer to the source from which they evolved into their abstract form. I discovered something in-between, an intermediate state, a thin thread that allowed me to move between states of correspondence, influence and critique.

This is not the first time you’ve corresponded with “ancestors” of modern art history (see also the text about the exhibition Objektiv, curated by Dalit Matityahu).

As an artist, I believe there is no real need to reinvent things, rather understand more in-depth what has been done previously. A bit like what they say in philosophy, “everything is a footnote to Plato.” There have always been artistic movements, and some are “returned to.” For me, what is important is to allow for a profound dissemination of the reading of the artistic motives of those who preceded me. With Vasarely, it was indeed a particularly intimate encounter; I literally lived in his apartment. Some who had seen the body of work I had produced with Josef Albers made another interesting point, telling me that already a couple of works seemed a response to Vasarely. So apparently, the connecting thread is common between the works themselves as well.

So what happened to all the photographs? What did you show in the exhibition and in the book?

It’s not so simple to explain the relationship between the book and the exhibition, or why I eventually chose not to present those photographs in the exhibition, while I had worked towards that for a whole year. Those who’ve seen the book and know about the exhibition take it for granted that I must have exhibited the photographs. The thing was that when the time came for me to exhibit, I was given the possibility to make use of Vasarely’s original materials and to create my own work from them. The very same materials that I had only been able to look at and photograph.

It made me think again of the “will within the material,” as almost a determinant. So, instead of using the photographs, I built structures for what would become a sort of sculptural garden. A garden is a site obviously consisting of nature, but which is “cultivated.” I used the tiles to build the sculptures, and the paper to make foldings that created the illusion of depth within the flat paper surface. Technically, it was very difficult to build the high-rising structures the way I had envisioned. You can say that the substances opposed a “return to nature.”

Could one say that the exhibition “failed” while the book “succeeded”?

Interesting. You might say that. The success of the book for me is the fact that it reveals an archive that would not have existed otherwise, and eventually will disperse. There are pieces in the book that I photographed that already today do not “exist” anymore, having disappeared into one of his works on display, becoming part of them just like a piece of a puzzle. At the end of my stay, I printed and bound the hundreds of photographs into a single edition and gave the entire archive to Pierre Vasarely and Fondation Vasarely.

Why didn’t you put all of the photographs into the book? How did you choose?

The book only has 61 “pieces,” made up of the missing fragment of a puzzle, a sort of missing puzzle, just like those works on view in the museum. When I returned to Tel Aviv, I met with Michal Sahar, an amazing designer with whom I had worked before. She was the one who made me see that it would perhaps be impossible to make a selection from this body of work. There were “good” or “bad” choices to be made when combining them. We therefore built an “editing machine,” using InDesign, which allowed us to randomly merge images together to become a spread. We ran the photos several times through this and were left with some wonderful spreads and obviously some strange mismatching ones as well. Combinations I couldn’t have imagined making.

Amazing, I would never think of working that way.

There was something liberating in introducing a completely mechanistic element into the process. Especially as I find it very interesting to treat my own work as raw material. As we progressed with the publishers, I told them about the way I had come up with and produced the mockup. They were astonished. Eventually, I had to persuade them to keep some of the more “out there” spreads, as they thought it was important for the edit to emphasize the organizational approach of the whole project, and to allow the book to communicate that better.

Essentially, you didn’t work closely with a designer.

That’s right. The book is in a way “non-designed.” I made certain decisions regarding the size, paper, and binding based on budget constraints. Though it was clear to me from the start that I wanted a cardboard cover that would allow for its association as a sort of archive folder. There was a stage where I really wanted the book to be pocket-sized, a format that would allow the whole archive to fit in your pocket and you would be able to “carry the archive with you,” but I abandoned the idea when I understood it wouldn’t be possible to include everything.

The current size actually very much encourages the page-turning experience. It turns it into a kind of industrial catalog, a color fan.

Yes, that’s true. The page-turning experience really accommodates that, and becomes significant and is exemplified because of the page size. The dramatic diagonals of the photographs are accentuated as you experience each photograph separately, yet you’re able to see the next while you leaf from one page to the next. At first, I really wanted the possibility and ability for the pages to be torn, for the photographs to be taken out; to emphasize the idea of how the tiles were “extracted” from the crates and would later disappear again, returning into the works. I wanted the pages to be able to exist on their own even when not in the book. Unfortunately, that was very expensive to do. When the first batch of books arrived from the printer in Belgium, several copies were damaged during shipping, and all of a sudden, for a moment, I had the book with the pages removed. That was a lovely moment and since then I have taken apart several copies and have once again been working with the photographs.

The book was published by a boutique publisher in Paris. This must be a pleasure to make a book, knowing that it will travel the world.

Yes, I do feel very fortunate about that. Thanks to the wonderful work of the publisher, the book is distributed to every museum in Europe, including Centre Pompidou, where it was on display during the Vasarely retrospective exhibition. It is also distributed to the other side of the ocean and available at Printed Matter and was presented at several book fairs. The book launch took place at Yvon Lambert bookshop, in Paris, a really wonderful and important bookshop for artist's books in all genres, photography, sculpture, architecture, etc.

Making a book is like…

It is a bit like, nothing else I ever knew. I mean, you are supposed to know so many things in advance, things that are almost impossible to know how they will turn out. The mistakes you make along the way leads to adjustments in the experience of the final object, even though the content itself doesn’t change. The thought that people will eventually take your book home is very special. I image that making a book is perhaps a little like building a house, but building it from the roof down. In my case, once the construction was completed, instead of moving in and living in it, I wanted to make another one.

Do you have an idea for the next book?

Maybe a second edition. There are still hundreds of photographs that I took of the archive that no one has seen yet. In the meantime, I have been taking all of the works I have ever made out of their respective context. I have taken the series apart and chose a single photograph of each, to represent the totality. What I am trying to do is to rethink my entire practice. I call this project Schnitt, German for cut. I already made a mockup for a book as well as for an exhibition, which I hope to be able to do. Also, I am currently in the midst of a project related to the origin of trompe-l'œil, where I am examining questions that relate to the principles of phenomenology. And of course, I hope to be able to exhibit the Vasarely materials in a local institution, along with a real exhibition catalogue.

Where can readers get a copy?

On my website, the publisher’s website, the Centre Pompidou bookstore, Idea Books, Printed Matter, Sternthal Books, and Antenna Books.

Oran Hoffman (b. 1981), lives and works between Tel Aviv-Yafo and Amsterdam. Hoffman holds a BFA from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy of Art in Amsterdam, as well as an MFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. His works range from photography and painting to sculpture and installation. In 2020, he presented a solo exhibition at the Lobby Art Space in Tel Aviv.

"Victor Vasarely objected to the flattening in painting, just when contemporary abstract art celebrated this. He argued that two-dimensional, flat surfaces are non-existent in Nature, and therefore for a work of art to include “mimesis,” namely the imitation of Nature, it needed to encompass a dimension of illusion. In other words; the painting was urged and “invited back into Nature” on the condition that it contained the illusion of depth."

"There was a storage room with materials that Vasarely had left. I asked to see it and the moment the door to this room opened was the moment the project was born."

"The success of the book for me is the fact that it reveals an archive that would not have existed otherwise, and eventually will disperse. At the end of my stay, I printed and bound the hundreds of photographs into a single edition and gave the entire archive to Pierre Vasarely and Fondation Vasarely."