When they knock on the door, then we are three –

You and I and the next war.

And when it is all over, we are again three –

The next war, you and the picture.

You and I and the very next war,

And the next war coming to us for a blessing.

You and I and the next war

The one that will bring proper rest.1

***

The book Nikhsey HaShulhan HaAvudim (The Table of the Lost Assets) opens with a portrait of a man. We cannot see his face which is blurred by the flash of a camera. It is as if someone photographed the photographic paper itself. On the next page is a photograph of a person standing in a photo booth. The curtain is pulled to one side leaving the booth wide open. The person inside it, his hands folded, looks relaxed. The bright flash of light on his face signals that this is the moment the photograph is being snapped. A photograph documenting a moment of photography. And maybe, the moment is a complete fabrication. Maybe there is no photograph being taken. There is a chair inside the booth; the person should be sitting when the photo happens. The light aimed at his face is too high. Looking at the image, the writer of these words begins to think that this photo is staged.

***

The title of the book Nikhsey HaShulhan HaAvudim (The Table of the Lost Assets), alludes to the Knights of the Round Table, although in this case, the knights are lost assets. Unlike King Arthur’s knights, these lost assets are the soldiers killed defending the homeland—the national asset—the central theme in Erez Harodi and Nir Nader’s artist’s book.

The book was published in 1993 during the duo’s exhibition The Act of Photography in the Confession Box at Bograshov Gallery. In the exhibition, which functioned as a commemorative site for the very act of commemoration, were small and large monuments displayed inside heavy, antique wooden cabinets, military shoes painted gold, chairs arranged on a stage facing an empty wall with signs that read “Reserved for the families of the fallen heroes,” a JNF donation box inside a glass display case, and replicas of medals with decorative lights above them.2

A month before the book’s publication, the two, who began working together in 1989, were invited to appear on a popular late-night television talk show hosted by Gabi Gazit. Also on the show that night were decorated IDF war veteran Avigdor Kahalani (who lost his brother in the Yom Kippur War, and went on to serve as a member of the Knesset on behalf of the Labor Party) and Nira Cohen, then chair of the IDF Widows’ Organization. Both Harodi and Nader had refused to serve in the Occupied Territories during their reserve service military service, and Nader also refused to serve in Gaza during the first Intifada (1987).

During the program, Harodi and Nader presented “Making a Living from My Father’s Death,” a work that was presented in the exhibition and in the book and which, as expected, made considerable waves. Harodi, whose father was killed in the Six-Day War when he was 6 years old, was the first to use the phrase. The words were pasted on plastic lace wallpaper, with a business card, apparently from a photography store, that read: “Transparent corners for 'Ta‘anug' albums are the best. Ta‘anug corners are thin so the album won’t bulge.”3

Other works from the exhibition shown on the program were the chairs, framed military shoes painted gold alongside the soles of soldier’s shoes, and a portrait of a woman’s neck. It would be an understatement to say that the audience's reaction was lively. “His mind is screwed up,” Kahalani said of Harodi, “all I can do is pity him. He grew up without a father.”

The phrase “making a living from my father’s death” distills the artist’s preoccupation with bereavement and memory, and expresses Harodi and Nader’s relationship with the Ministry of Defense and the IDF also reflected in the book. After his father’s death, besides financial support, Harodi and his mother would receive birthday cards from the Ministry of Defense and cards marking the Independence Day celebrations (also presented in the book). Harodi’s personal “earnings” become the raw material for asserting a national claim about the country’s real and spiritual livelihood from the industry of war and the deaths of soldiers, which serve to strengthen the logic justifying warfare. The elevation of the value of death and war over life.

Image and Confession

The book is fragmented. It has no beginning or end. Images are presented as a cacophonous stream of consciousness of state–army–sacrifice–photography. The works are a combination of images from the family albums of the two, which have been disrupted or treated, texts and photographs created by the artists, letters that Harodi and his mother received over the years as a bereaved family, flyers from photo labs, a target practice sheet from a shooting range, a photo taken by Harodi’s father, IDF information sheets like “Tzalashon” (which teaches standard Hebrew), and an ad for stationary—paper, envelopes and notebooks (“American work at an Arab price”). Harodi and Nader also asked five writers—Ray Robinhalt, Chaim Luski, Yaron Ezrahi, Ariella Azoulay (who also curated “The Act of Photography”) and Henry Unger—to contribute texts to the book.

The duo’s preoccupation with the non-photograph-photographic-act is evident in their decision to use existing images. A black and white photo shows a woman flipping through a photo album. She holds the open album while looking at the camera. She could be any woman, in any country. Above the photo is a sentence typed on a typewriter: “The act of photography.” Below it:

A man photographing his lover. She resists, she is interested, and she is captive in a world of images. She resists out of a different game, the man/woman struggle involving the mutual activity of conquest and sex. She is interested because the man took “it,” the part of her that is found on top of unused silver halides. She wants to know how the man sees her. The man argues back that she should be interested in the way she sees herself in relation to him. She points to “fumbling,” “obfuscation,” “invasiveness,” and “curiosity”; a kind of investigation with unclear results. The man stops taking pictures of her, now she is captive in a world of photographed images. There’s no need to take any more photographs.

From 'The Table of the Lost Assets'.

The uniqueness of Harodi and Nader’s actions lies, among other things, in their ability to perform a photographic act without pressing the shutter, or as written on another page of the book: “I want to show an attractive man in a photograph.” Like a child tugging at his mother’s dress, Harodi and Nader tug again and again, as if waiting for a mother’s attention, to see how she will react. It seems that the two chose deliberately to point out the aggressiveness in photography, as Susan Sontag wrote: “There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera.”4 Well aware of the power relations inherent in photography, and in the very act of disrupting or adding text, or ridiculing the image, they point to the way in which the State of Israel uses bereavement and mourning to legitimize its militant nature.

The sentence “There is no need to take any more photographs,” teaches to the power of photography as object, the transformation that occurs at the moment of photography, taking ownership—the woman’s image is no longer her own. The attention here is mainly on the relationship between the photographer and the photographed, as the two refer to it in the text under the heading “Eternal Confession.” A faded white frame appears below, indicating that there used to be an image there that is now lost:

“What the photographer holding a camera sees, takes place naturally inside the emulsion cells. He exists–he existed . . . the emulsion saw images. The emulsion saw another confessor and kept his secret to itself. The eternal act of confession is preserved in the emulsion. Temporality that sustains the act of confession forever.”

According to Harodi and Nader, not only is the intended moment between a person and the camera a moment of confession, and not only is the image taken and the photographed (person) possessed but also the inner desires, passions, inner core, the spirit, are taken too.

Private Memory As Asset

On one of the pages of the book is a letter that Harodi’s family received to mark Israel’s twenty-fifth Independence Day:

Dear family,

The people of Israel celebrate twenty-five years of independence and freedom. On this occasion, we remember and praise our loved ones who sacrificed their lives for the establishment of the State of Israel serving in the Israel Defense Forces. With sorrow and pride, Israel Defense Forces soldiers remember our loved ones who sadly are not with us on this day. We know that only thanks to their sacrifice, of which there is none higher, are we able to celebrate this holiday. We mourn for our fallen heroes and in their memory, we lower our flag. In their light we will educate our soldiers and their names will accompany us through the generations.

Reading the book today - after more than 200 days since October 7th - makes it clear how much greater the value of death is than life in the State of Israel. One hundred and thirty-three Israelis who were abducted by Hamas and remain in captivity, some no longer alive; over 1,400 Israelis dead; over 30,000 Palestinians dead; hundreds of thousands of Israeli and Palestinian families that have lost loved ones, are displaced from their homes, living in constant fear, in financial difficulties, in hunger, and without proper medical care. The current government normalizes mourning, pain, and loss as an inherent part of the lives of residents of this place. Life is trivial, death is ubiquitous. The preoccupation of Harodi and Nader with these issues back in the ’90s teaches something even more painful; the dimensions of the normalization that sacrifice of life for the homeland has undergone over the three decades that have passed since then.

On another page we see the backs of two photographs on which are written by hand: “A view of the Temple Mount from the Intercontinental,” and “A view of Mount Zion from the Jaffa Gate.” We do not see the images themselves, but the text triggers the imagination to conjure the image. The Temple Mount and Mount Zion are visually etched in Israeli memory. Immediately following is a photograph of two children, their backs to the camera, with the words “Unified Jerusalem,’73” on the back of the picture. Here, too, the children, whose faces we cannot see, could be any child, from any family, making pilgrimage to the capital. The word “unified” next to the date ’73, (the year of the Yom Kippur War), adds an essential element to the picture, manifesting Harodi and Nader’s criticism of the war industry and the semantics of the occupation. Whether it was taken before or after the war, it echoes the message of the paratroopers in the Six Day War: “The Temple Mount is in our hands.” One doesn’t need a photo of Jerusalem to evoke the image, one doesn’t need to see the photo of the paratroopers next to the Western Wall to recall it.

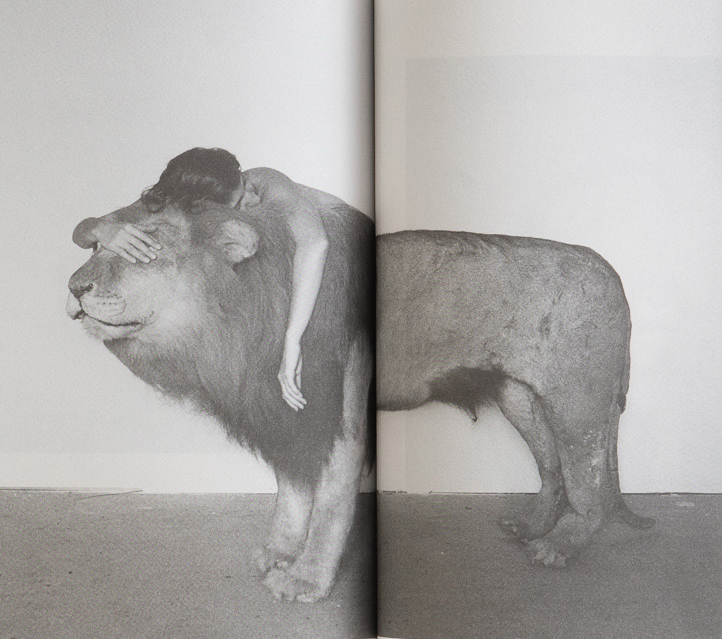

Harodi and Nader combine truth and fiction, as for example in the text “Places Absent of Commemoration,” in which the artists tell of an encounter with an old man who is deaf and blind. The man is sitting in a shop full of photo albums and frames, “Everywhere the man is surrounded by the intoxicating drug, the drug of memory.” The unknown person walking around the store full of coins and medals (the medal also appears throughout the book, and on its cover, as a symbol of heroism and commemoration) wants to find his coin in it, that is, his memory, his private grief. In The Table of the Lost Assets, Harodi and Nader, by playing with ready-made, existing images, and text, place a mirror before the reader. In a defining moment like the current war, when art is put to the test, when the moment of creation from nothing seems impossible, Harodi and Nader’s book allows us to look critically at the images currently surrounding us.

***

The book The Table of the Lost Assets ends with a photograph of two men in a photo booth. They sit opposite each other. The curtain is closed. We cannot see their faces. They are sitting comfortably, or so it seems, their arms resting on their laps. It is not clear if they are having their picture taken or just sitting in the booth. Maybe they are waiting. A photo of a photo? It doesn’t matter. The writer looking at the photo knows the photo is staged. She is captive in a world of images. Images of soldiers, war, and killing. Images of the sanctification of death for the homeland.

***

Footnotes

- Hanoch Levin, “You and Me and the Next War,” in Sketches and Songs 1: What Does the Bird Care, ed. Yehuda Melzer, Muli Melzer, Menachem Peri (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1987). [Hebrew] ↑

- After the exhibition “The Act of Photography in the Confession Box,” the two taught photography in a high school (Ironi 7) in Tel Aviv, opened up a wedding photography studio, and exhibited their iconic work “Preparatory Assembly for the Supreme Court,” through which they criticized the appointment of Ronnie Dissentshik as director of La National Insurance Company, and the local art industry. ↑

- 'Ta‘anug' means pleasure in Hebrew. ↑

- Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), Kindle edition. ↑

Gal Houbara Bergman (born 1996) is an Art journalist, writer, researcher and freelance curator. She holds a bachelor's degree in Art History and in The Multidisciplinary Program In The Arts from Tel-Aviv University. Her writings have been published in Portfolio Art & Design Magazine, Galleria (Haaretz newspaper Art & Culture section), Time Out Tel Aviv, and more. She is the founder of a non-profit collaboration with ArtGirlRising devoted to the work of local female artists (Mekomit محلية מקומית), and a co-founder of a non-profit organization raising awareness on gender inequity & sexual abuse (This Is Us).