You have already made three artist’s books and one concertina booklet. We thought this conversation was an opportunity to talk about all of them in the context of the themes that occupy you as an artist. So let’s start at the beginning if there is one. When was your love of books born?

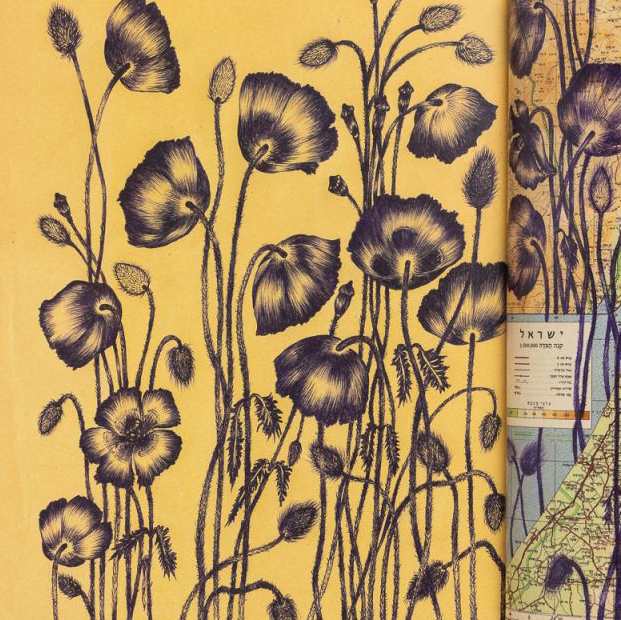

The love affair started already during my studies, during my first year at Bezalel, but the first artist’s book I presented was at the Petah Tikva Museum of Art (Agro-art, curator: Tali Tamir, 2015). I made a work about Palestinian and Jewish agriculture south of Mount Hebron in the West Bank. This is an area where the way agriculture is used for “creeping occupation”—that is, to expropriate land from Palestinians—is very present and aggressive. What’s more, each side has completely different agricultural technologies, and access to water is unequal, as is also the case with access to the land itself.

I worked with the report by Kerem Navot, an Israeli civil society organization, and in collaboration with Dror Etkes who is an expert on Israeli land policy in the West Bank, and tried to check the visibility of these processes using photography. Very quickly, I switched to working with images from Google Images, aerial photographs, which on the one hand have something threatening about them (as an Israeli you see an area from above and you immediately think of a bomb that’s about to fall there), and on the other have something wonderfully pastoral, a lost paradise of beautiful vineyards and vine terraces. Some of the photos look like they were from wine regions in Europe.

I was very troubled by the gap that was created between what I know about what is happening in this area, and how it looks in the photographs—the anomaly that is rooted in the visual field of this place (Israel/Palestine). Generally, I have an aversion to photography, precisely because of the regime aspect of it. In this project, I tried to illuminate the policing of the gaze, and through editing to create a conversation. I created a concertina that turns the view “from above”—the rational, military view, if you will—into a “horizontal” view, a view that stretches to the horizon, out to the sides, that tries to be more descriptive; I listed several models of Jewish agriculture there: the vineyard species type, access roads, traces of modern agricultural tools, irrigation, planting for commemoration and more.

Photo by Elad Sarig.

How did viewers react?

It was interesting. Many pointed to the places where they had served in the army. They spoke about their experiences in those places. I was happy that I was able not to point a finger of blame, but to invite people to experience a place they know one way in another way. The book created a condition that I think images displayed on a screen have a hard time creating.

This is an interesting point from which to pivot to Fichte and Olympia, the two other books you made, both of which deal with the tension between national and family myths, and how feelings of attachment and empathy play a deep role in the way national ethos works on us. A tension that is very activating and fertile for your art. The two books, which grew out of exhibitions but also stand on their own, deal with a deep experience of fragmentation, between identification with and disconnection from the ethos.

I’ll start from some sort of beginning. Fichte, the exhibition and the book, began with exploring my grandfather’s memories from his hometown of Bayreuth in southern Germany. My grandfather was born Günter Aptekmann in 1920. As a child, he managed to be in the German youth movement, where he studied navigation and orientation, which served him very well in his later years, and I’ll soon expand on this. In 1934, when he was 14, he left. He left behind his mother and his brother, and immigrated to Israel with nothing.

He recorded the full story with my cousin, Uri Yoeli, and later we found out that the family had been a social welfare case. His father, Julius, had abandoned him, his brother and mother. When he (my grandfather) arrived here, he joined the Haganah, and with his background in topography, he was made responsible for the “village files” (the process of mapping Palestinian villages, initiated by the Haganah in the 1930s), and mapped the Negev—through photography and mapping. He had an incredible analytical ability that led him to become one of Israel’s pioneers in computerized mapping.

My last name, Yoeli, is actually his father’s Hebrew first name—Yoel. When the State was founded, he changed the German surname “Aptekmann” to “Yoeli.” He actually carried the wound of his father’s abandonment with him in the family name.

So Fichte grew out of these conversations?

I couldn’t listen to that recorded conversation with Uri Yoeli; it was too painful for me. But I read the transcripts, and I realized that my grandfather was drawing a map with words, his stories were a kind of mental map of his youth. Every place he mentioned is connected to the story. I found 14 points he talks about, 14 stories related to his childhood in Bayreuth. For example, he said that there was a spot behind the synagogue, on the riverbank, where he used to carve boats from pieces of driftwood. There was a story about the barbershop where they made him a beard for a role he played in a school play, or one about the factory that produced buttons out of Polynesian mother-of-pearl that bankrupted the family. I found clues within his story that helped me locate the specific places he talked about.

The conversations made you want to travel. What did you want to have happen there?

I realized that I could only go there with my family, with my partner Yuval and my son, who was a year old at the time. We found a hotel, whose location I realized later was itself one of the points my grandfather spoke about. The hotel was called The Leaping Deer. A genius name for a small place full of taxidermy animals. My contact was a genealogist who knows the area really well. He asked me what I wanted to see, and I replied that I wanted to see the views that my grandfather saw. He helped me find all the spots.

And what did you do when you found them?

The first thing I did was collect fresh flowers from the spot itself, whatever I found, and run to the studio I had built in the little hotel, and photograph them with really good window lighting. When I got back to my studio in Israel, I printed them, cut everything out, and started putting together artificial wreaths—basically, wreaths made from the photographs of the fresh flowers. For every spot my grandfather told me about, there is a memorial wreath that is constructed like a victory wreath. The tradition of making wreaths, to mark a military victory or the loss of soldiers in battle, is originally from Prussia, which is actually an evolution of the tradition of Germanic ceremonies marking spring. There is something so paradoxical that the tradition that is supposed to represent renewal and youth, has become a cultural symbol of bereavement. How this tradition took root in Israel is also fascinating: there was a “yekit” (Hebrew slang for someone of German origin) kibbutz member in Kibbutz Gan Shmuel who decided that to celebrate Shavuot, she would make wreaths from stalks of grain, which later turned into the flower wreaths that are now used in military ceremonies in Israel. I felt that I had to do something with this tradition, which actually evolved through the German tradition into the Jewish-Israeli military ethos in Israel.

The second thing I did was to hang the camera at the level of my heart—and click, without seeing what was being photographed. I was thinking about how there are usually two types of traditional “photographic heights”—eye level and waist level. Both rely on sight. I wanted to create a new height—heart height, which is also mid-way between the two. This was my way of “putting myself into the map,” of acting in a way that does not try to act on the place as an outside observer or from a distance, but as an act that undermines the tradition of mapping a place with a camera.

This heart-level is great, and how you phrased this action is poignant. Apropos the middle, the book is divided into two parts: the first part is the wreaths next to the coordinates of the places where the flowers were gathered, and the second part is the photographs from heart-level, which are not explained; they look like frames from a movie without a plot. In the middle of the book there is an abstract drawing. What actually is at the heart of the book?

It’s an “erased” map of the city, a kind of image of a failed map. I took the map of the city from the 1920s and cleared it, cut out all the houses and institutions and statues and left only a network of passageways. By the way, the coordinates that appear are real, so if you happen to be strolling around Bayreuth, you’ll find that each of these points exists. In one of my grandfather’s stories he told that as a child, he guided a blind man (named Reinhart), who lost his sight in the First World War. In the winter they’d skate on the ice, and one day Reinhart’s skates cut my grandfather’s hand. Only then did I understand how he got the huge scar on his forearm that I knew so well.

When did you realize that his stories wouldn’t make it into the book? What motivated that decision?

I wanted the book to be “displaced,” like my grandfather was. If I had included the stories, a specific context would have already entered the displaced experience of the foreigners and the images. I wanted the effect of the “embalming” of memory, which happens to the souls of people who are forced to leave a place quickly. It is impossible to put all the pieces of the story together. What’s more, my grandfather, even after 70 years, longed to return to his hometown. His birthday was in July, and every year his wife (my grandmother), who thoroughly hated Germans, men and women, would make him special dumplings “from back home.” And look, artists do a lot of unnecessary things. What's more, as much as it seems to me that I distance myself from the stories through art, or distance art from the specificity of the story, the stories come back to haunt me.

What do you mean by “haunt”?

I’ll give you an example. When I signed up for a student exchange, it was obvious to me that I’d be going to Germany, and I wanted to find the place farthest from my grandfather’s hometown. So I went to Hamburg. As it turns out, that place was my grandmother’s hell. In 1944, she was brought from Auschwitz to a labor camp near Hamburg. With the liberation, she and her friends followed what was left of the railroad tracks until they reached the town of Ludwigslust. When they arrived from hell to the pastoral town that bloomed in the amazing spring of May 1945, they decided to “take revenge”: They told the townspeople to go to their gardens, cut the beautiful and well-kept flowers, and throw them into the river.

I wasn’t aware of this story when I made the work in Bayreuth—now, what are the chances that I would cut flowers, in a city by a river, and make memorial wreaths out of them, when I didn’t even know this story beforehand? By the way, in October of this year I went to Ludwigslust for the first time. I did a traditional papier-mâché baroque sculpture workshop there and a small tour. I even cut flowers there and here they are in my studio.

It sounds like there will be a book from this journey as well.

I’m certain. But look, in that regard it’s important for me to say that the fantasy of getting lost is a very privileged fantasy. A fantasy of people, like me, who can afford to go on study trips. But the second option for me is to constantly be in control, and this is also a kind of collaboration with the power system that assigns us roles ahead of time.

Apropos educational trips and dealing with Germany, so in the series of works The Last Robinson you corresponded with the German tradition of coming-of-age journeys, and in Olympia with the ceremonial aesthetics of Leni Riefenstahl.

Yes, the series of drawings The Last Robinson was based on 19th-century German books for boys—coming-of-age books, like Hasamba (a popular series of children's adventure novels written by Yigal Mossinson [1917–1994]). The story is always about a group of boys, who find themselves out in nature, where it’s difficult for them and they overcome it, and mature. I took a book from the series, removed all the elements from the illustrations, deleted all but one of the characters from each page of the book. These are drawings that rely on erasure and disappearance.

I put the drawings in a notebook that the artist Hila Laviv sewed for me. Each page spread was sewn and framed. An intimate dimension was created with the book, which became a kind of drawer hanging on a wall, a movement from the horizontal to the vertical in terms of looking. The work was presented in an exhibition curated by Dalit Matityahu in 2016 at the Tel Aviv Museum and was called Rootless.

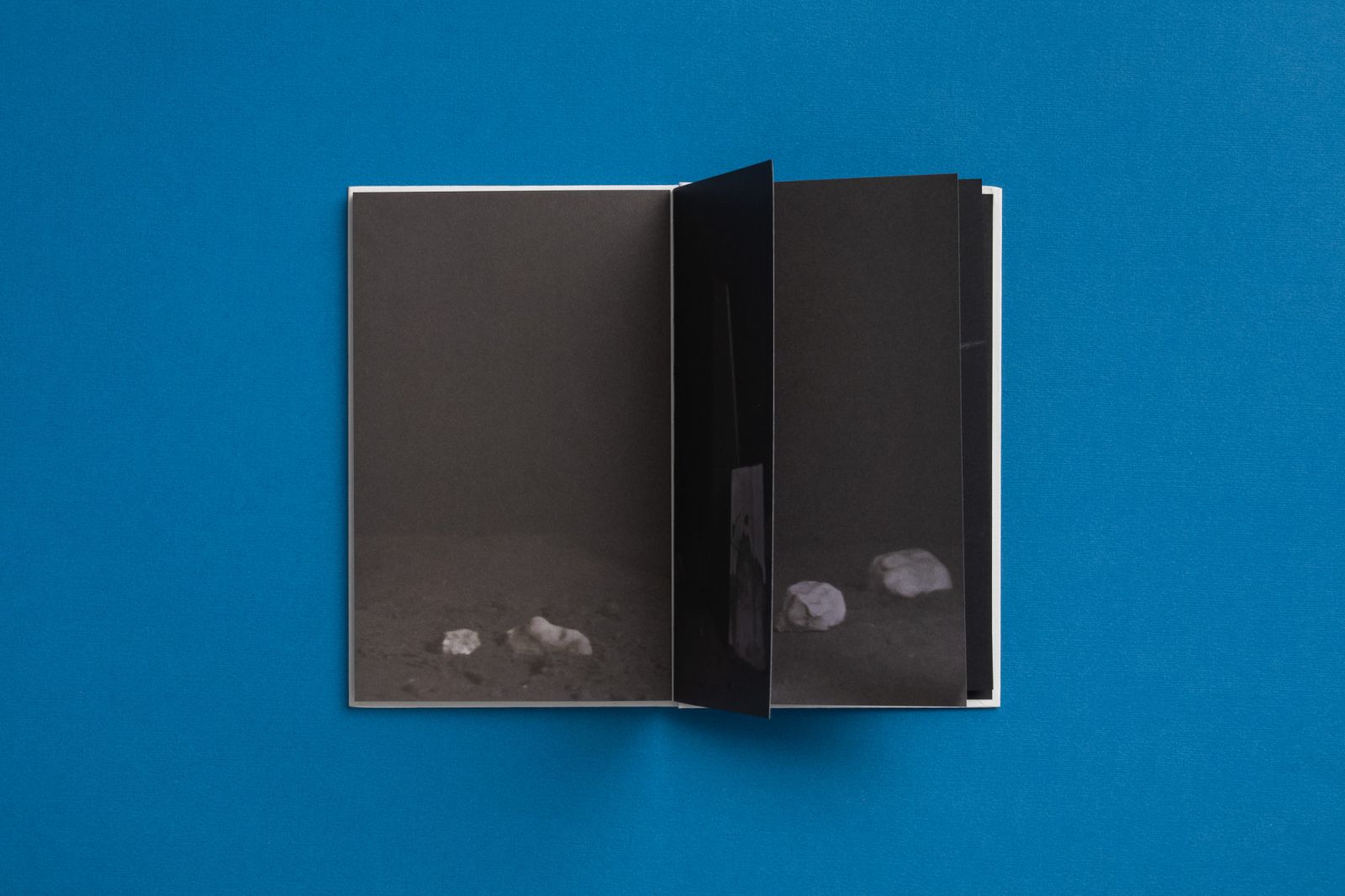

Now, Olympia is actually a catalogue of an exhibition curated by Aya Lurie, but we wanted it to stand as a book on its own. The exhibition was presented in 2017 at the Herzliya Museum, which has a wall that adjoins the Yad Lebanim house. I was interested in this tension between the white cube and the memorial space. “Only in Israel,” as the saying goes, would these two spaces be linked. The exhibition space was very dark, a corridor led to the first room, where you would have encountered a large black screen, on it was a video with the sound of a metronome and wind, and inside it a miniature model that I photographed in the studio of “artificial” ruins, all drawn and fake. Like a memorial site that blew up, or a military exercise at a security facility gone awry. The film was a loop, and was shot in the studio on four-meter-long plates.

The title Olympia, I of course took from Leni Riefentsahl’s film. As we know, she was a groundbreaking Nazi film director, partly because she filmed on a moving cart, the so-called Dolly, when she documented the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany. Her film opens with a German runner climbing to Olympus, toward the Olympic flame, a shot that connects the Greek and German people and illustrates how architecture and film editing alter consciousness. I situated the climb to Olympus in the Israeli desert, in a scaled-down model in the studio.

On the other side of the large wall in the exhibition, there was another film, filmed inside a miniature theater in my studio, in which there was a series of invented ceremonies in 7 different acts. Everything was filmed, without effects, in the tradition of European theaters of the 19th century, a continuous film with the sound added during editing. In the first act, I arrange Roman ruins; in the second, there is a sunset against the background of the ruins; in the third, a cave with a mosaic from Zippori and a horse from the Parthenon, which is in the British Museum collection (all in miniature); in the fourth, a bunker; in the fifth act, a commemorative site with a burning fire I put out using litter from my cat’s litterbox.

For the sixth act, I asked my aunt, Naomi Yoeli, who is a theater person and puppeteer, to breathe life into a marionette skeleton I created in the tradition of the artist James Ensor or the New Orleans carnival. In the last act, everything was actually buried in real sand that I poured on the set, and as in archaeology, things are always “revealed” in layers, actually “buried” in layers. It was important for me to produce a ceremony that is entirely “fake.” For me, part of being “wired” into “Israeliness” is the way commemorative ceremonies affect us without words. This is “the Israeli abstraction.” You are standing in front of a display of “the worst thing of all,” and the smallest nuances activate the whole mechanism: a knock on the door, fire, a flower wreath.

You made a nice adaptation of the video in the book, by inserting the time codes into the frames for the double spreads. This emphasizes the specificity of the transition between the chronological time of the film as a video work, and the mythical time in which the film actually takes place. These are like coordinates that point to a time we don’t have access to.

Noa Schwartz, who designed the book, is a genius, intuitive and brilliant. We wanted the book to correspond with the tradition of a written play, as if the film is made in acts. To produce a kind of liminality of the object, in practice—a play made entirely of “images.” Noa designed the logo of the book and the project by studying Greek script and fonts.

The book works from both sides, which is to say, you can also experience it from the end to the beginning.

Yes, I also like that we insisted on a small size, which created a situation where the book can be held and read like a Greek play; it is a kind of miniature in itself in relation to the monuments it refers to. All my works are “a model of a model.” There is a world within a world and the principles of the model have taken over reality. In The Reawakening (1963), Primo Levi describes his return home to Turin at the end of the war and his experience of the return to reality as a dream. The horrifying power and scale of the lager (the camp), the disrupted relationship between the model and reality, and he finds himself feeling when he returns home as if he were dreaming for a moment and will suddenly wake up back in the reality of Auschwitz. I think that art is a way to deal with the fact that we are a step away from the post-traumatic “flashback,” in other words, we are constantly “inside a model,” dealing with it. Even the respite from it is contained within it. It’s an insight that terrifies me but also makes me constantly want to undermine the structure.

So, if we may end with the topic of intergenerational transmission, during the coronavirus you made a coloring book for children called Aleph-Bet [Home Press, 2020]. It’s a book with wonderful illustrations according to the alphabet. A “simple” book?

Yes, I was looking for something to do with the kids at home, and it took me back to my love of dictionaries, and travel guides, which are similar insofar as they attempt to bring order to the world, and therefore are (also) immersed in colonial language and imperialist motivations. I tried to take the issue of language to an open and non-didactic place, and I asked the children for ideas. So, yes, you could say simple.

Making a book is like...

Making a gift.

What book should we add next to our library?

The Order of Things by Nana Ariel, published by “Home Press,” a publishing house established by Uri Yoeli and Nana Ariel.

Where can we find your books?

On my website, or by direct messaging me on Instagram.

Dana Yoeli was born in the United States in 1979 and lives and creates in Tel Aviv-Yafo. She received her BFA and MFA from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. A multidisciplinary artist, Yoeli creates large installations, video works, photographs, paintings and sculptures, which mainly focus on the tension between the personal narrative and the collective ethos, and the role of nostalgia, memory and commemorative ceremonies.

"The tradition of making wreaths, to mark a military victory or the loss of soldiers in battle, is originally from Prussia, which is actually an evolution of the tradition of Germanic ceremonies to mark spring. There is something so paradoxical that the tradition that is supposed to represent renewal and youth, has become a cultural symbol of bereavement. How this tradition took root in Israel is fascinating."

"I wanted the book to be “displaced,” like my grandfather was. If I had included the stories, a specific context would have already entered the displaced experience of the foreigners and the images. I wanted the effect of the “embalming” of memory, which happens to the souls of people who are forced to leave a place quickly."

"It was important to me to produce a ceremony that is entirely “fake.” For me, part of being “wired” into “Israeliness” is the way commemorative ceremonies affect us without words. This is “the Israeli abstraction.” You are standing in front of a display of “the worst thing of all,” and the smallest nuances activate the whole mechanism: a knock on the door, fire, a flower wreath."

"Yes, I also like that we insisted on a small size, which created a situation where the book can be held and read like a Greek play; it is a kind of miniature in itself in relation to the monuments it refers to. All my works are “a model of a model.” There is a world within a world and the principles of the model have taken over reality."