Unwrapping a hand-made, hand-sewn book is an exciting moment. How did it all start?

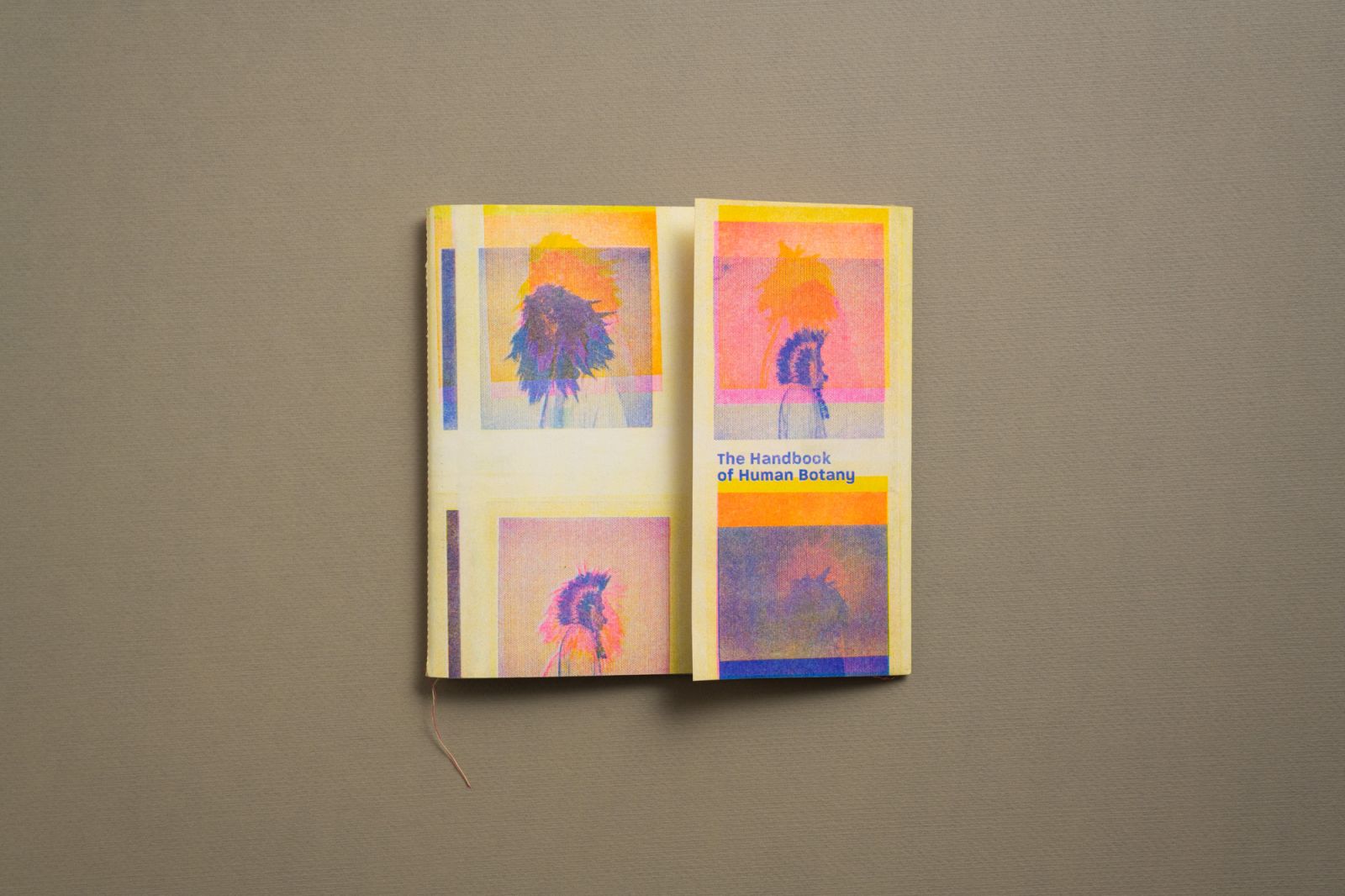

The book was made using Risograph printing, with a Zine machine at a two-and-a-half month residency at HaMehoga, TAtarbut in Tel Aviv, during which you learn how to self-publish a magazine and, among other things, work with a Riso. But I jumped in over my head and created this artist’s book.

What do you think is the difference between a fanzine and an artist’s book?

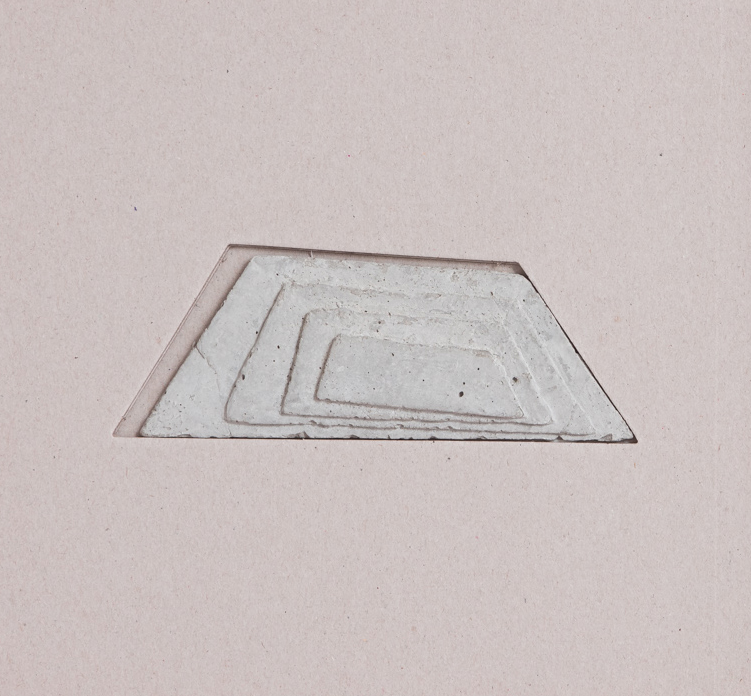

There is something immediate about a fanzine. It’s made on a low budget, with less effort. In my book, the materiality is important. I use thick paper instead of regular fanzine. And while fanzine can come in any form and material, I still think that there is a different gravity with a book. Maybe this is what it wants – to be something more complete, to last for longer.

You made fifty copies of the book. That’s a very small print run.

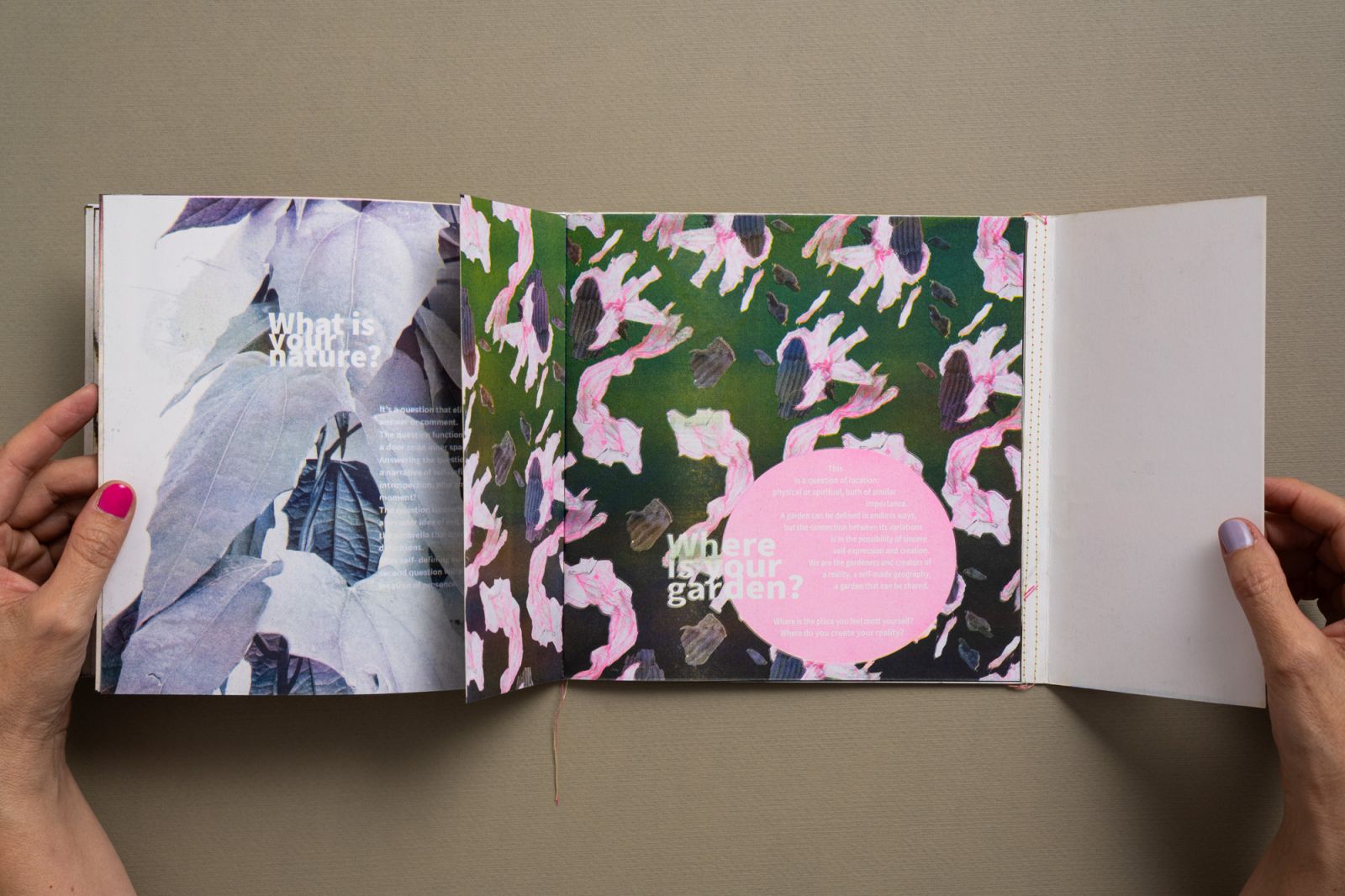

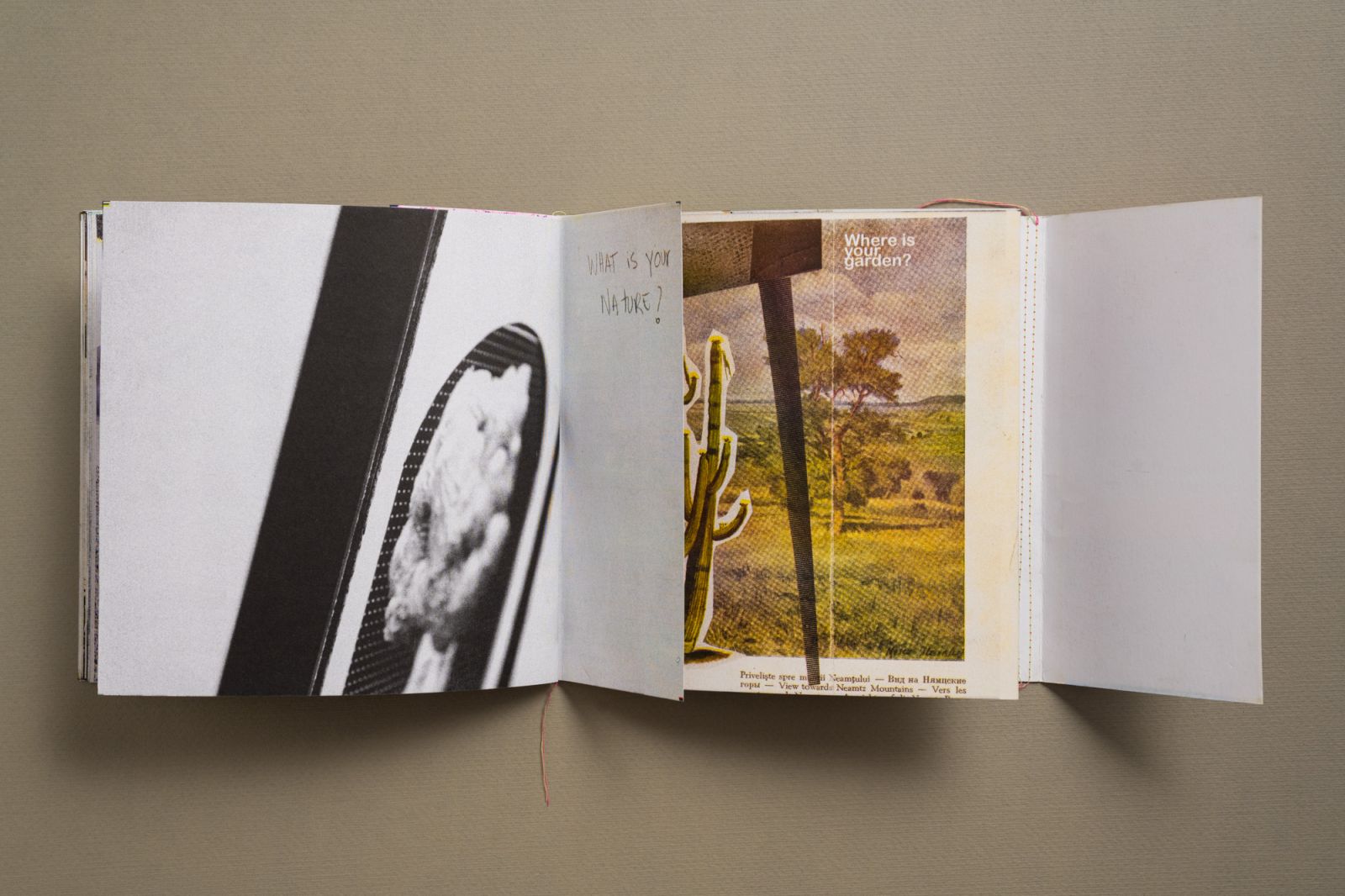

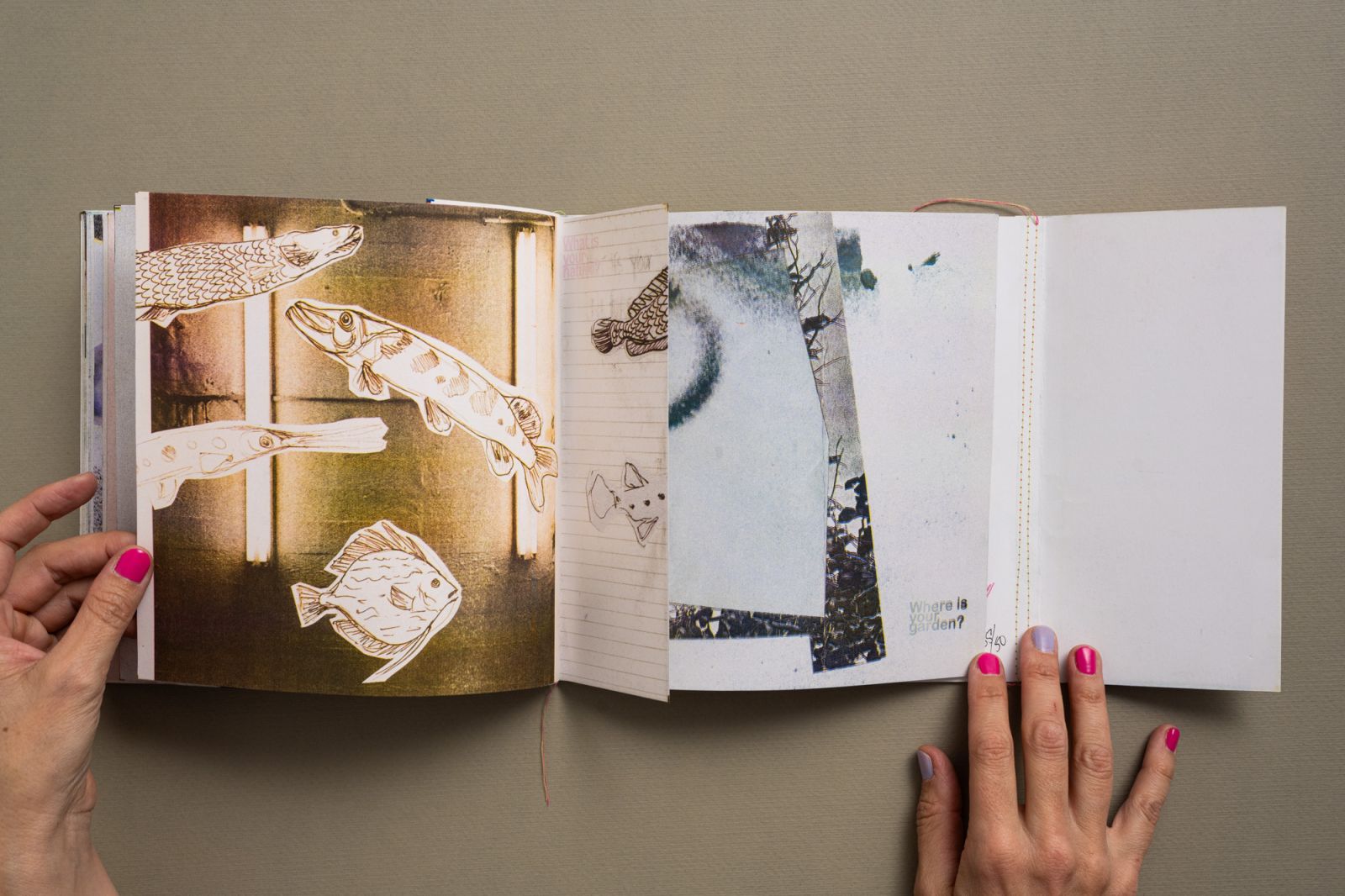

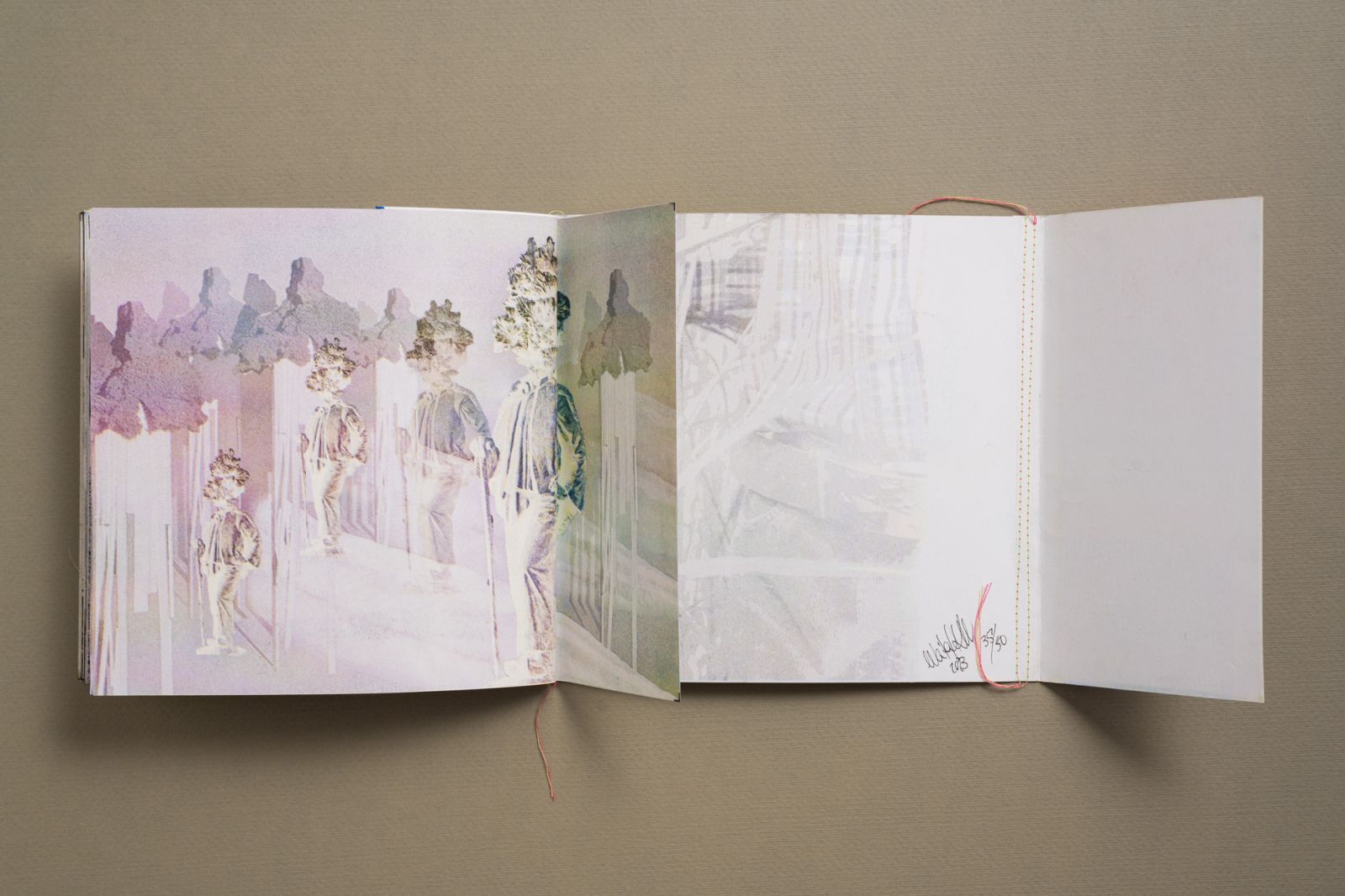

Yes, but it’s a lot of work. In Riso printing each page is run through four times on both sides. You actually print each color separately. You have the image that you’re dividing into layers of color, and you choose which colors to use and which combinations to do in each layer. Each color and layer brings in other details, and you only see the complete image when you have printed all four layers.

Often in Riso printing, and in your book as well, you see the lack of precision, the printing happens almost next to the image, so that it creates duplication. Is that on purpose?

Those who know Riso know that this is something that happens and then you can actually either try to control it or accept it as part of the technique. It’s annoying when it happens on letters, but interesting things happen when it’s on images. Sort of like ghost images.

Riso has been gaining in popularity lately Do you have any idea why?

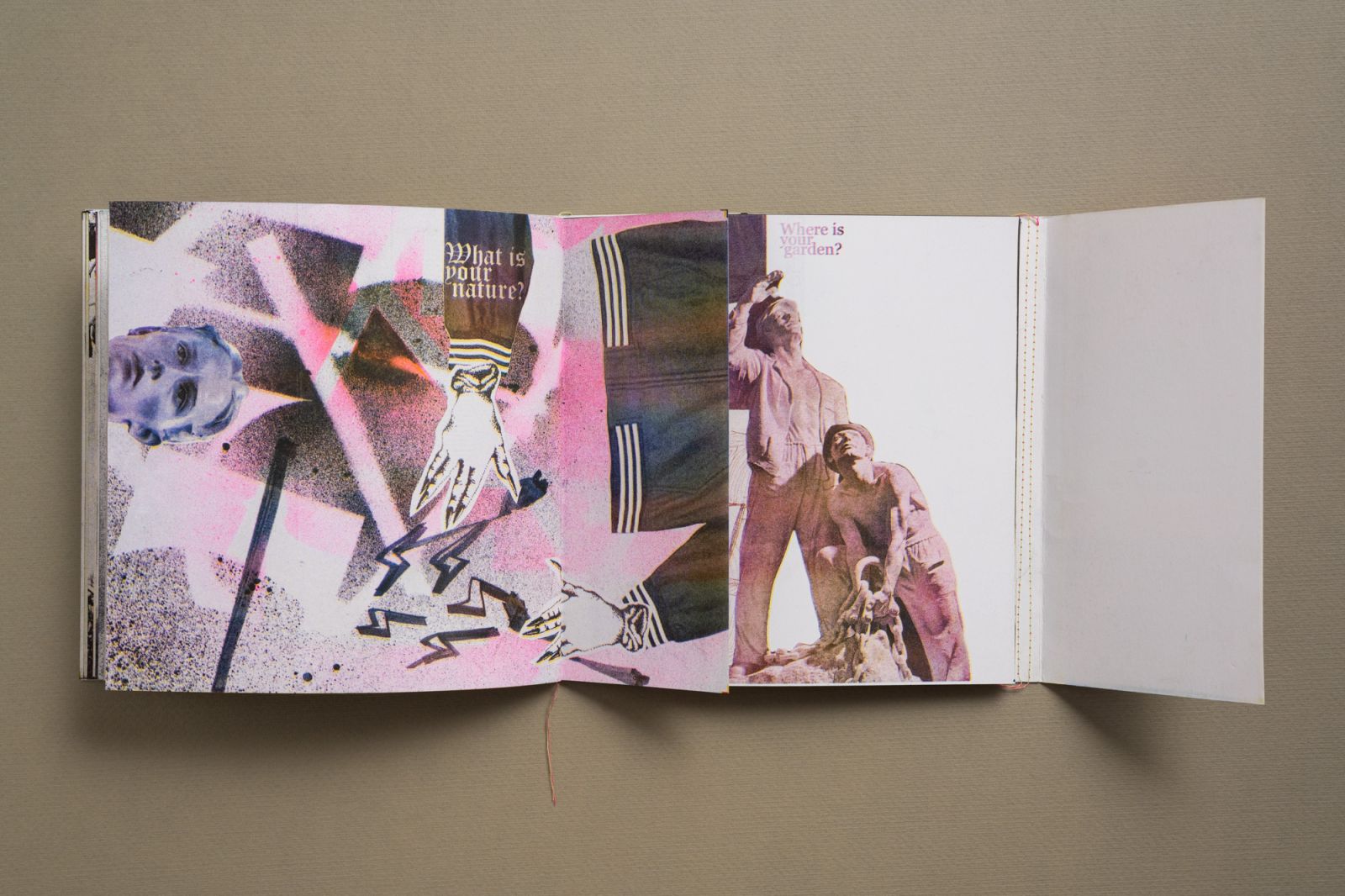

I see it as part of the return of punk subculture, and I think it has to do with sustainability awareness. They go together. With Riso, the ink is made from rice (hence the name Riso). It’s an organic ink, a living substance, so it’s always changing. And there is a strong return to old practices of many types of craft, and this is a type of urban craft. In my opinion, the concept of returning to things that are touched by the human hand is part of what has come back. Today, it’s considered almost radical – Riso, weaving, working with textiles. Things that are not computerized. I am very connected to the craft school.

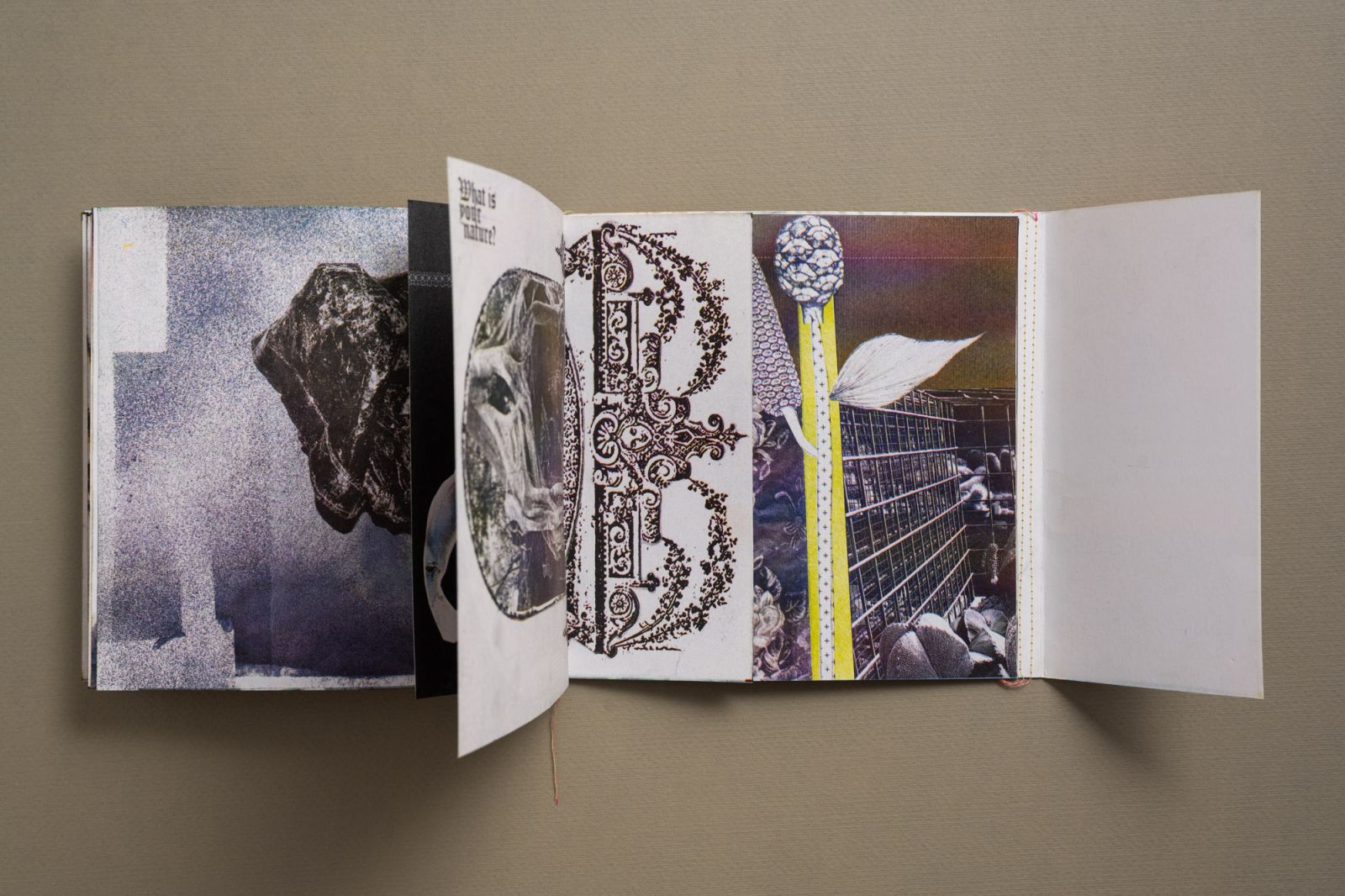

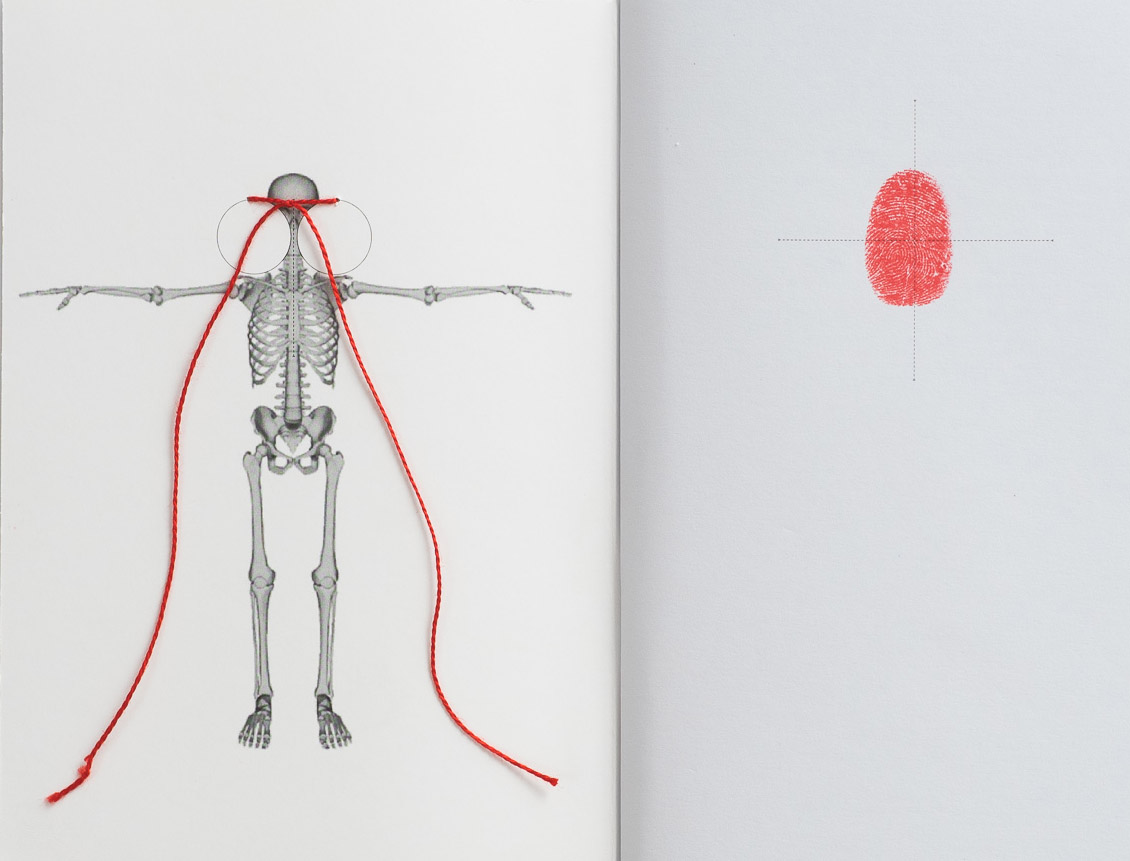

The book is full of images, some of which look like they were taken from your previous works.

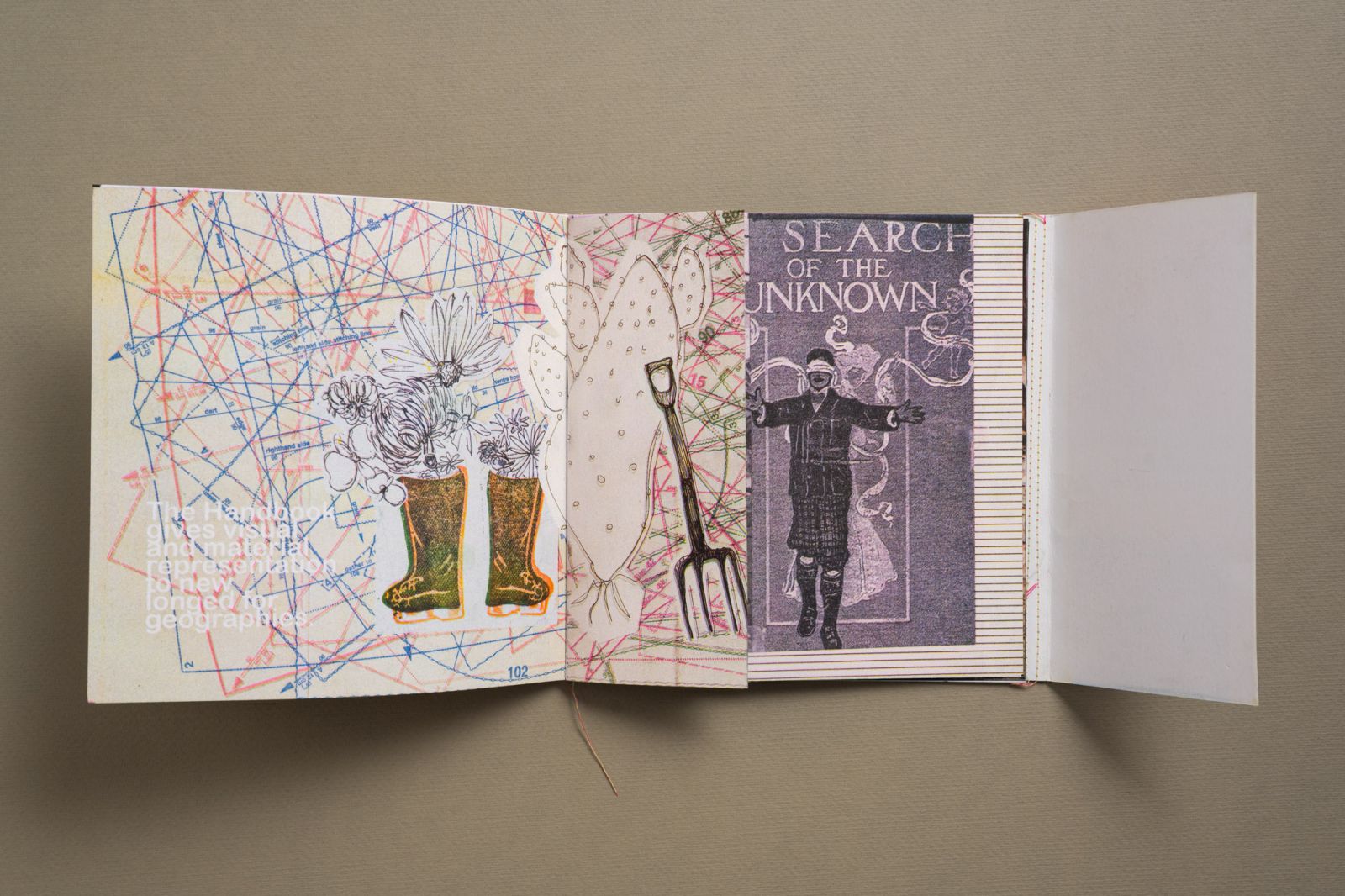

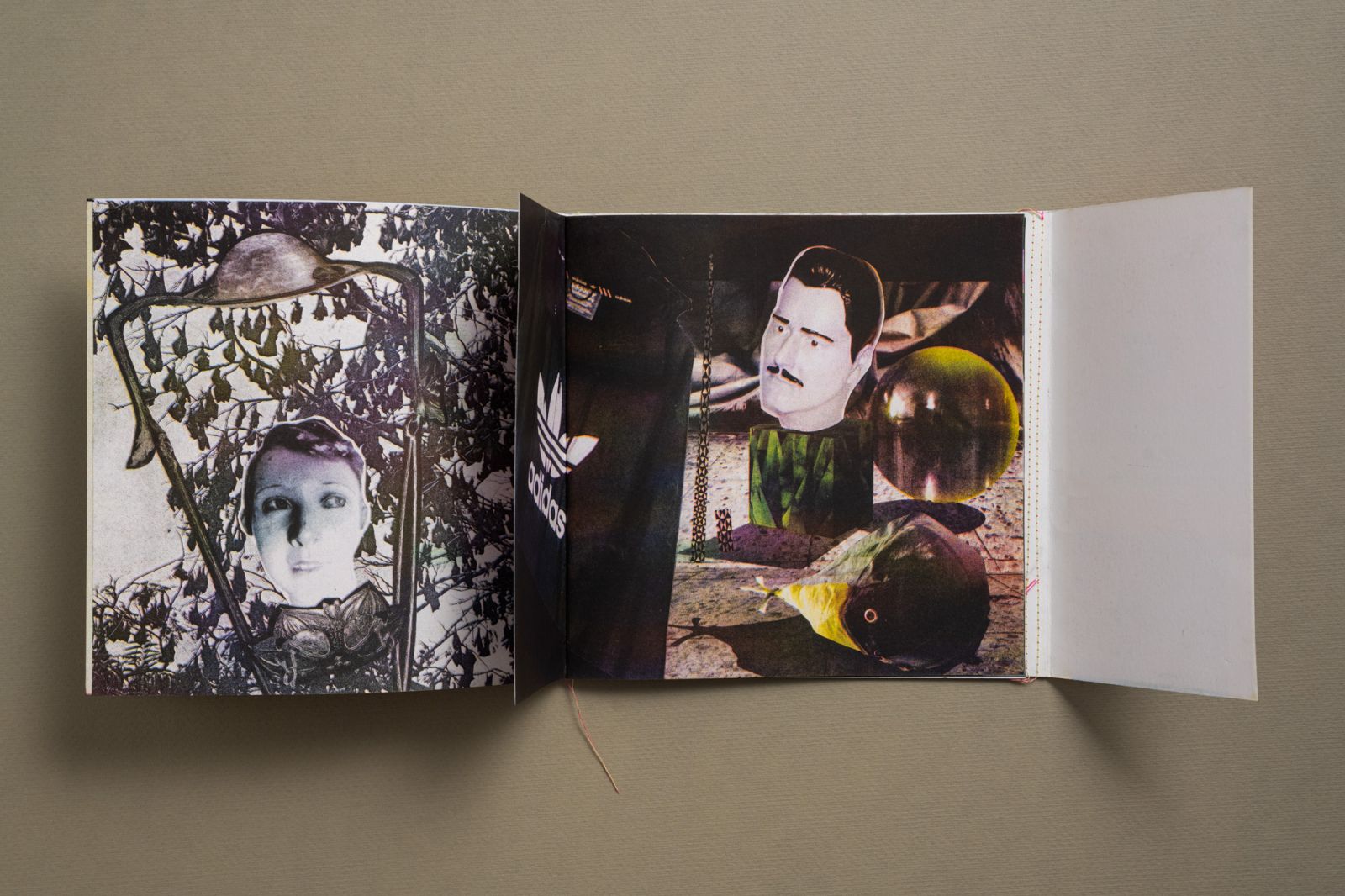

I used a lot of collages in the book, and sketches for previous works, some of them from my research. A lot of things were pulled from drawers – with me, everything is divided into physical folders – and they were given a new life. Lots of old Xeroxes and erasures and combinations. The cactuses for example are research for a project I did. Photographs from places I visited, for example greenhouses that grow cactuses in terrariums, and a place that grows ancient cactuses. Then I worked on the design of the text inside the image and the narrative.

Can you say something about the questions you inserted?

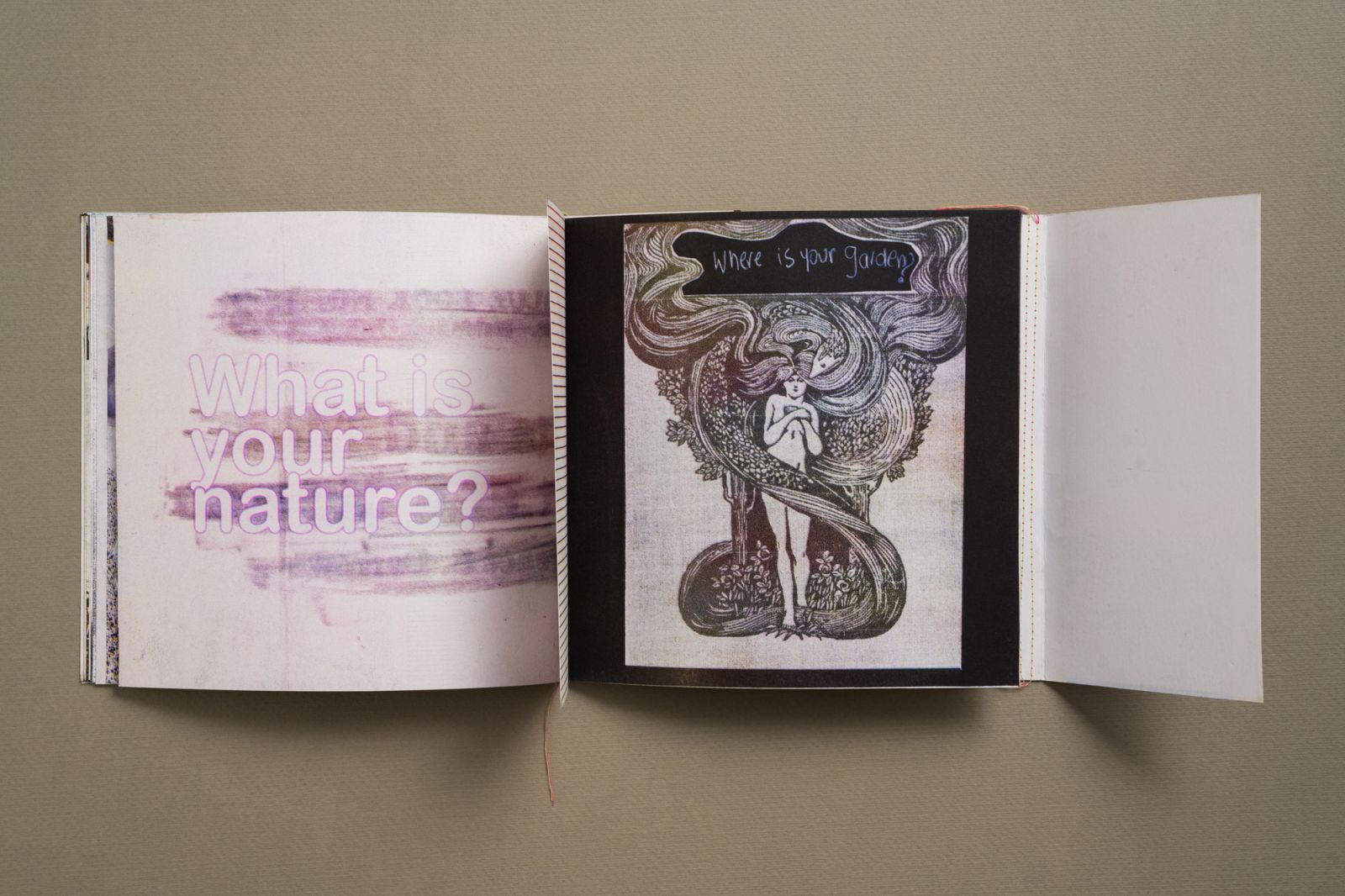

The book invites a moment to stop and think. In many ways it talks about this period, which I didn’t realize when I made the book, but actually over time has become even more relevant. The book talks about society’s demand to take a very specific side. There is a requirement to separate into groups, and I say in the book that there is something very basic that connects us and to find out what it is through two questions that appear in the book and are an invitation for observation: what is your nature and where is your garden. It’s an invitation for introspection. What am I and what is my essence, my nature.

People usually say about someone that they have a certain nature, but I’m interested in the question of how you talk about yourself, how you understand your own essence. The question of where is your garden is actually a question of territory – where do you situate yourself at this given moment. This is a question about my garden, the place where I am the chief, the organizer, the planter. It’s an attitude that empowers my nature within a specific place.

Beyond the metaphorical garden, do you also have a real garden?

Yes. I always have a yard. I had one in Venezuela, and when I arrived in Israel in 1995 I moved to Kibbutz Bar’am and grew kiwis and apples in the orchards. And after that I grew my own garden.

The book invites the reader to answer these questions. Do you think people will really answer? I feel that in a lot of the books and notebooks that you can write in, I don’t dare do it. I don’t want to ruin the book with my scribbling.

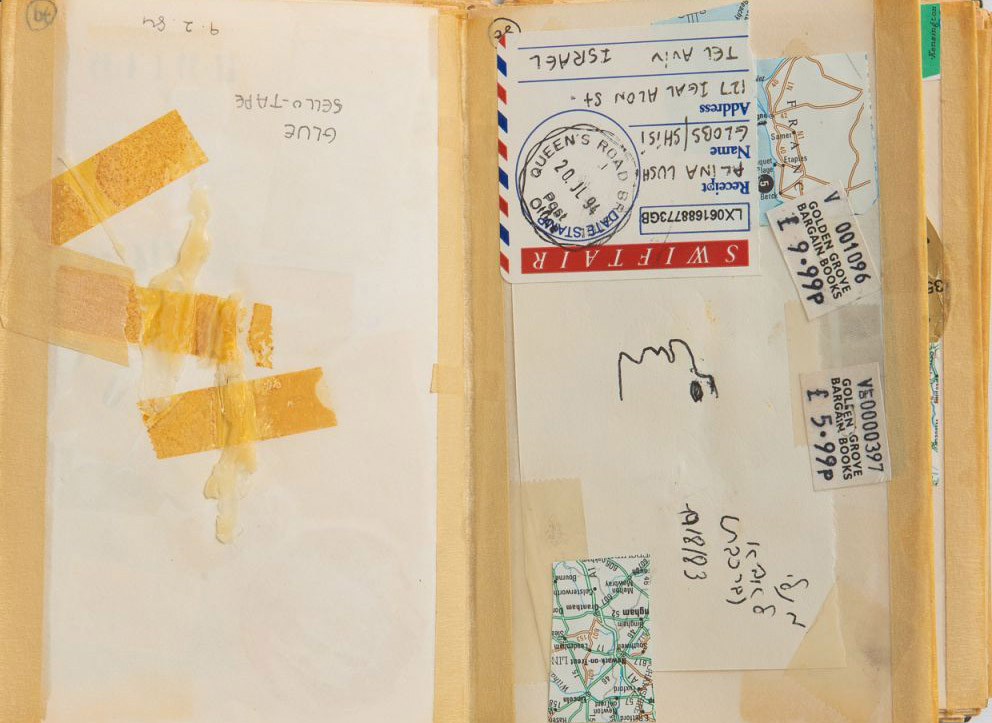

In the middle of the book there is a letter to the reader inviting them to fill in all the remaining pages. I hope people do. I hope they write, draw, make a collage. I understand the fear of writing inside the book, but I say – let’s turn it into some even more “precious” and meaningful than it was originally. We’ll turn it into a personal testimonial at some point.

The answers people give are very interesting to me and have been guiding my artistic research for several years. I think that between the two questions lies some truth through which we can understand the world better. But the questions are so big, open, and yet also specific, they allow for a moment of internal dialogue and dialogue with the surroundings. I am very interested in trying to create a database of answers to these questions.

You mean, ask people to share with you the things they wrote in your book?

Yes this is my dream. To ask people to upload the answers to a site from which we can extract statistics and play with the data in a way that will reveal things about the world.

It’s interesting that you talk about data, because I would have thought that the answers to these questions would be very poetic.

You can play with it. See how many answer the question with a physical place. And of those who answer questions and talk about gardens, how many of them have gardens? And how many people talk about a fictitious place. I want to turn it into material that can be played with.

I think the book has a therapeutic dimension. It comes to fix something, to bring something to our consciousness, to ignite dialogue, to gently and delicately bring up thoughts that we didn’t dare think about. It very much connects to what we need right now, in my experience. Like giving yourself a hug when you feel anxious. Something unmediated, you are alone with the book, you can take it anywhere you want, draw in it, answer it, read it a million times. I happen to like pragmatic things that are born from subjective places. Maybe this is the way to deal with difficult issues.

Is the place where people will write also the reason for the different sizes of the pages in the book? It ranges full pages to smaller pages, and both sides of each page seem to adapt to the pages that come before and after it.

I decided to produce a different type of leafing, a short page and a long page, to allow double leafing and other options for a page, such as a notebook inside a book, a piece of paper where you can write things down if you don’t want to go overboard. Every page works on both sides and reacts to the page before it – sometimes generally, such as to the color, sometimes to the text, and sometimes to the image itself. I planned a lot of it, but there were also combinations that happened by chance.

It is important to say that, to me, the book feels complete even without writing things in it.

I hope it’s because it came from a complete thought.

Who would you like to dedicate it to?

I would like to dedicate the book to my children. I feel it can be a kind of life guide. A book that is possible to return to it at different points over time and to be more precise about moves and choices and above all to maintain one’s identity in moments of confusion.

Making a book is like…?

It’s like building a house (I just finished mine). Making a book keeps you clearheaded. It’s a process that asks to see the big picture and at the same time also the tiniest of details. And like a house, a book also opens a space where you can wander and linger.

And finally who should we invite next to Madaf to share their artist’s book with us?

The two artists who were with me in the residency made very beautiful books – Flora Debra made a book of drawings and her poetry, and worked with transparent rice paper. And Dori Ben Alon made a fanzine that is like a municipal archive folder and researched Atarim Square. It really looks like an archival document but everything in it is a bit real and a bit made up.

The book was supported by Alvit R. Sharvit - Alvit Contemporary Creatives.