How does a book come into the world?

I knew that I wanted to make an experiential book, in which time is a key element. I wanted to control the rhythm of how it is viewed and unfolds, like sculpting with pages. I treated the book like a box, a chest—which one begins to discover what’s going on inside it by flipping through it. It began with the structure, then I made the pages, and then the technicalities of binding and sewing had to be resolved. I usually start with sketches and drawings, so the book is also a rendering of the processes of the work and the thinking about its very construction.

You created a completely sculptural, one-off object in the sense that each copy is assembled by hand.

I realized that I was giving expression to the sculptural ideas that preoccupied me, and that it was the physicality of the raw material that guided me. The image I had in mind was of a “pit.” Not a metaphorical one but more like a “site” into which visual content is poured. I started thinking about how to carry out this action, and I realized that I was creating a book that is actually a shaft that could serve as a negative space of the block that is at its base. Technically, I began realizing that I needed to stick with the idea, but break the creative process down into stages. At first, I thought of casting actual concrete into the book, but it was too complicated technically. I resolved this by casting a block, which is embedded inside the binding itself. Each cast is done separately and the entire structure rests on it.

The casting is hidden from view when one opens the book—as you said, the book is kind of like its own negative. How does this relate to your perception of sculptural space?

I gave expression to the inherent possibilities of the pit, of what could be inside it. The pit also creates the illusion of a pyramidal structure when one looks at it. When I started sculpting, I found that I was engrossed by building materials, they spoke to me. They’re discarded and I collect them. I sometimes also buy materials at contractors’ locations, depending on the scope of the project. Wandering around construction sites, you experience pits that in no time are going to be towers or parking lots. Tracing these constructions fascinates me.

The scaffolding work, exhibited at the Herzliya Museum and currently on permanent display on the entrance wall of the Minshar School of Art, emerged from a photographic process. Photography defines the environment from one point of view, as does painting for the most part. The artist is responsible for the perspective and the angles. That was missing for me in sculpture. Sculpture is perceived as something freestanding, and you revolve around it. You situate it and the viewer decides from what perspective and angle to look at it, how to relate to it. There’s openness in all directions.

I started feeling as if I wanted to make sculptures that were restricted to my point of view as the one observing the object, and also as the one recreating what I see. I complete the knowledge behind “how something is built,” by way of the construction itself, and it becomes another potential point of view within the work. I create a kind of illusion through sculptural means, and thereby try to liberate the perspective in a way that will surprise me as well. To see the behind-the-scenes of the object. Sometimes things find their more suitable place like that.

What preceded what? The drawings or the three-dimensional element?

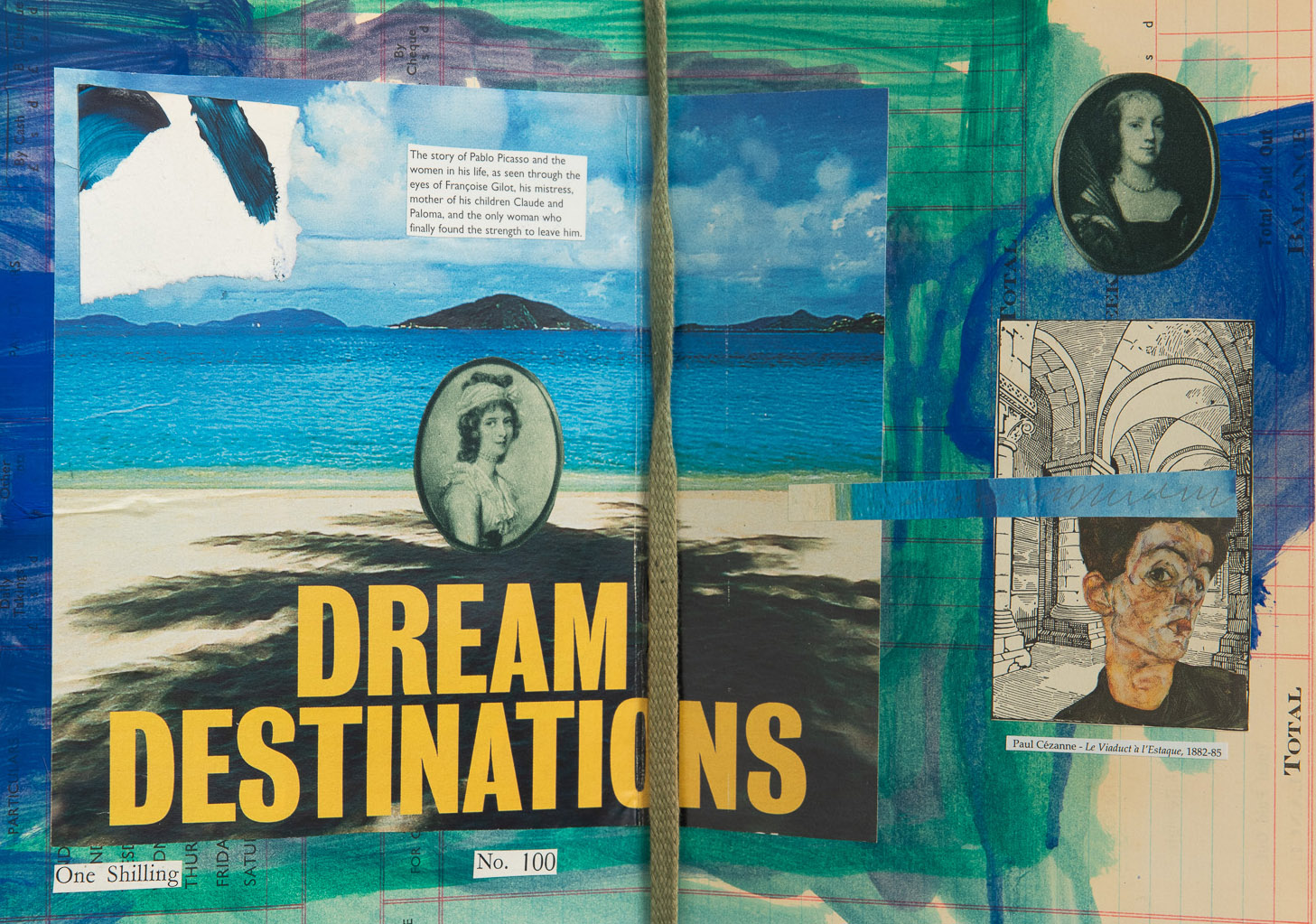

The stage when I decided to incorporate the drawings within the book was when I realized I didn’t want the book to just be an “idea”; that as soon as you open it you get it. I wanted to prolong the discovery, and illustrate an environment and a process. The book became a game between the pit and the page, a language of occurrences around the shaft.

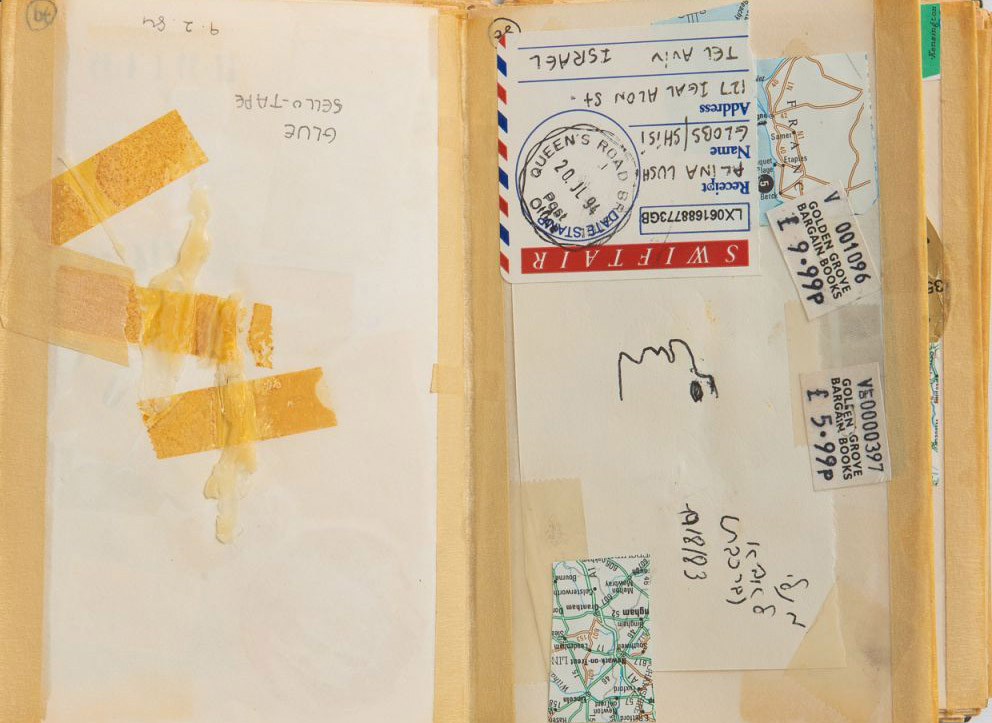

Most of the drawings were actually series I had done as part of a structural analysis. I took white sheets of paper and made holes in them, and I started to draw on these, every time with something else in mind; sometimes it’s a drawing of my studio, the yard, the floor. There are also drawings of Jerusalem, for example, in the cemetery in Givat Shaul. These were different visual materials from the period, sometimes integral to the book, sometimes less so. After that, I scanned the drawings one to one, so that the thickness of the pencil remained the same.

How did you assemble the book?

I created a silicone mold into which I poured concrete, and took it out 24 hours later. The trick for the complicated binding was to create a sleeve in between every two pages and to glue each sleeve to the cover. Then I thread the drawing papers with the drawings inside each of the sleeves separately. The bookbinder created cardboard cover that holds this structure together.

This is a Sisyphean task of sculptures.

Yes. A book is made only because of some madness. You have no idea what it is. The second time around, you already understand that it’s nuts. Also the printing house, the bookbinder, and the printer all told me “Take this, and don’t come back.” All this was made possible thanks to one of the binder’s employees. She took on this challenge as a project and thought of all the possibilities.

How many copies did you make?

240 copies were printed, and so far, 130 books have been “constructed.” Now I’ve run out of copies, and I have to sit down and recreate the workshop here on the table at home. Compiling pages takes a good few hours.

You don’t feel like changing the order of the pages?

I was just now thinking of doing that. Because I have all kinds of drawings that weren’t included previously in the book. I like editing the prototype that’s created, the “this” versus the “that.” I treat the book as spreads, as pairs. Maybe I’ll change the current order in the next round. We’ll see.

You also staged an exhibition of the same name, Vertical. What’s the difference between the book and the exhibition?

The exhibition touched on sculptural situations at construction sites. For example, I sculpted a table that construction workers build, or a builder's chair. It included all kinds of furniture and constructions that are built on construction sites, which are the expression of the builders’ abilities, and not necessarily things related to the building itself. Props that they live with on a construction site. Drawings from the book weren’t presented at the exhibition. The book was presented in its own right at the exhibition.

You grew up in Jerusalem, and you’ve lived in Tel Aviv for many years. Have both cities had an impact on your preoccupation with construction sites?

I grew up in Jerusalem, our family goes back seven generations, and I always thought of it as a cosmopolitan city. Something about the place itself is the winner of all the wars waged over it. For example, I learned that you can’t build on Mount Scopus because there’s no rock inside it. Jerusalem is built like this: they dig and dig, reach the rock and then build the foundations of a house on it. The city and the mountain decide what gets built where. There's a reason why the cemetery on the Mount of Olives is where it is. It wasn’t possible to build anything else there, because buildings would have sunk.

My memories of construction sites in Jerusalem are of explosions. To break boulders apart, one has detonate them. I remember one day as a child, playing on a tennis court when the Palestinian workers shouted in the distance, “Barud, barud!” which means explosion in Arabic. Then there was a huge noise, and in the sky, we saw a dot approaching us. A rock about the size of our living room at home fell onto the court. That was some piece of rock.

To me the connection to the book is very clear…

Yes, probably. I participated in the Across From exhibition as part of the Jerusalem Manofim Festival in 2017, curated by Rinat Edelstein, Lee He Shulov and Tamar Manor Friedman, at the Mormon University Gallery on the Mount of Olives. I did a work there called Raising Holes. I built a sculpture that was on a ramp along with wooden beams, which created an illusion similar to the one in the book. A pit that is also a pyramid, which was reflected in the view of the Old City opposite it.

As a child, I had no idea that the neighborhood of Kiryat Hayovel, on the way to Ein Kerem, was also full of Palestinian ruins. I didn’t understand that these were once villages whose residents had been expelled. Everything seemed to me to be “Jerusalem.” I remember later, visiting friends in Malha, and them telling me that they had moved from the transit camps to houses that had stood empty since 1948. One day a family came from the Dheisheh refugee camp. They went into the yard and told my friend’s family that it was their house. His parents invited them in and there was a lot of crying. This is the Jerusalem I am discovering now, with eyes more wide open. Things are intertwined in my work, but indirectly.

What did you learn about book-making that everyone should know?

I remember that during the production stages of the book, I spoke in terms of the page order, and suddenly the book disintegrated into technical terms, into the language of printers and bookbinders. I had to contend with very technical questions all the time. It took a while for the book to become “mine” again, to be the original idea. I felt like I was constantly resolving problems and constraints that I never would have thought of. The process takes you to places you cannot imagine.

Making a book is like …

It’s like making a living sculpture. It’s like what paratroopers say about parachuting: the first time—you jump, the second time you’re scared. The first time you parachute, you’re not afraid because you don’t know what it’s like; the second time you’re more cautious. This book encapsulates the adventure of the first time.

What book should we add next to our library?

Every one of Uri Gershuni's books.

Where can readers get a copy of your book?

By personal order, via email: grharlap@gmail.com.

Ra’anan Harlap, born in Jerusalem in 1957, lives and works in Tel Aviv-Yafo. He holds a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. Harlap creates sculptures that explore the relationship between the second and third dimensions and the act of construction, topics he addresses also through drawing and painting.

״The image I had in mind was of a “pit.” Not a metaphorical one but more like a “site” into which visual content is poured. I started thinking about how to carry out this action, and I realized that I was creating a book that is actually a shaft that could serve as a negative space of the block that is at its base.״

״I grew up in Jerusalem, and I always thought of it as a cosmopolitan city. Something about the place itself is the winner of all the wars waged over it. Jerusalem is built like this: they dig and dig, reach the rock and then build the foundations of a house on it. The city and the mountain decide what gets built where. It’s not for naught that the cemetery [on the Mount of Olives] is where it is. It wasn’t possible to build anything else there, because buildings would have sunk.״