Before we begin, I must hear from you how you see the book. In the articles and reviews about it, it is called a graphic novel. But because you are a video artist and the storyboard format, which is similar to the format of a graphic novel, is part of your artistic work, is it an artist’s book or a graphic novel? Is there a difference in your case?

As a result of everyone calling it a graphic novel, I sometimes also call it a graphic novel, but I see it first and foremost as an artist’s book. In the graphic novel, there is a law of narrative and fiction, which I didn’t take into account as much. I looked at it more as storytelling of the kind I am used to in video works. When I made it I wasn’t thinking about the category of book it belonged to but about a book that stands on its own.

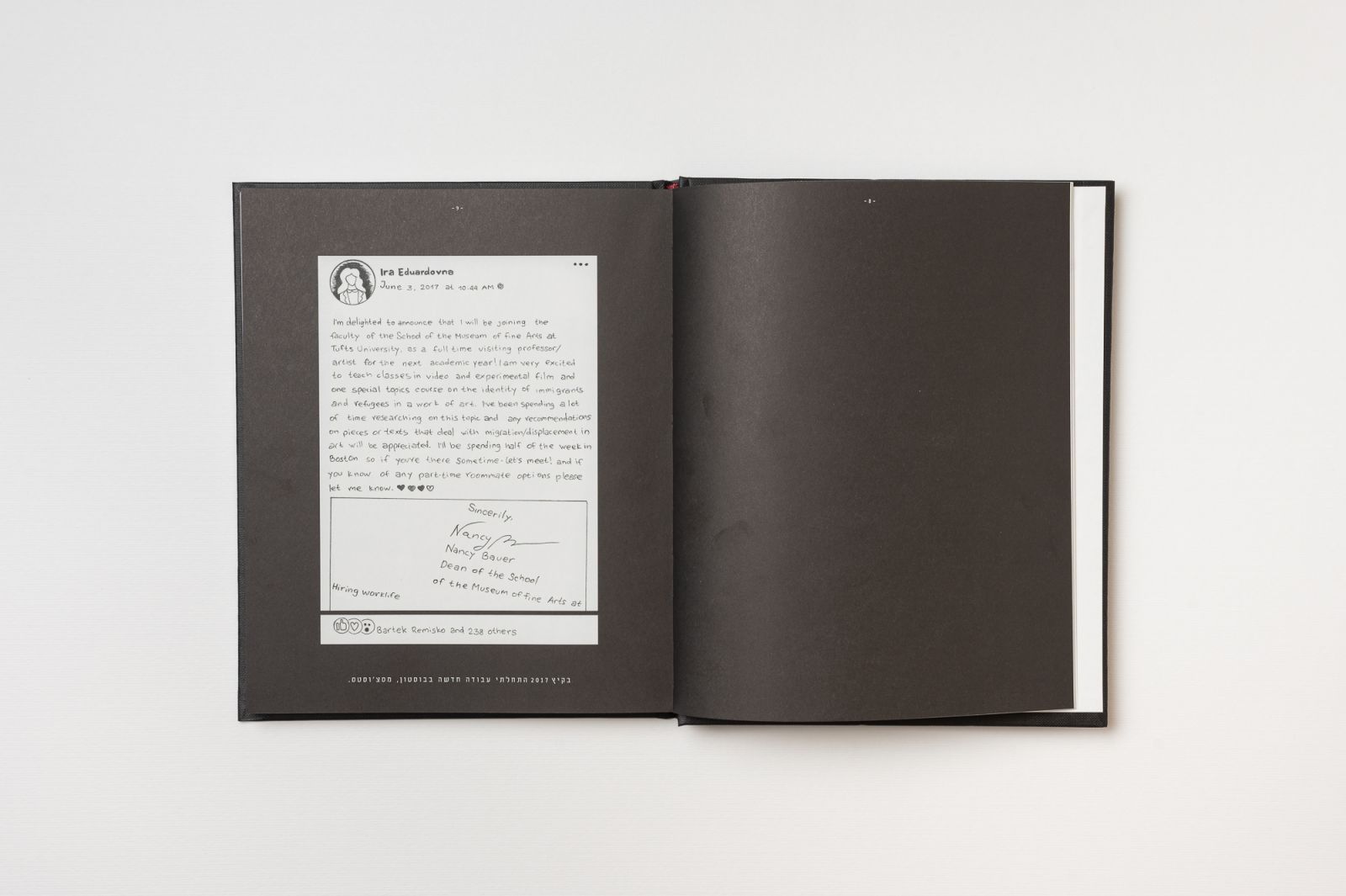

This is your first artist’s book, then. Unlike your video works, it tells a longer and more complete story. Readers get a broad understanding of your personal immigration story. I have to say that this is a surprising move, in the video works you allow us a momentary glimpse that is also time-sensitive, and here you have shown all your cards. You tell the reader directly how the book came about; the first sentence in the book is “This project was born under strange circumstances” and immediately following is the account of an accident in which you slipped in the snow. We are placed behind the scenes and find out that the book happened by accident; that without the fall there would be no book. You gave away all the secrets. What is it like to tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end?

It’s weird, it’s very revealing. I think in the process I felt comfortable because I don’t really think about it until it comes to fruition, when there is an exhibition or in this case a book. When it meets up with people’s reactions and I am asked if the story really happened to me, I want to respond: “It’s a book, it’s characters.” I do want a bit of distance, even if everything is woven from my personal experiences.

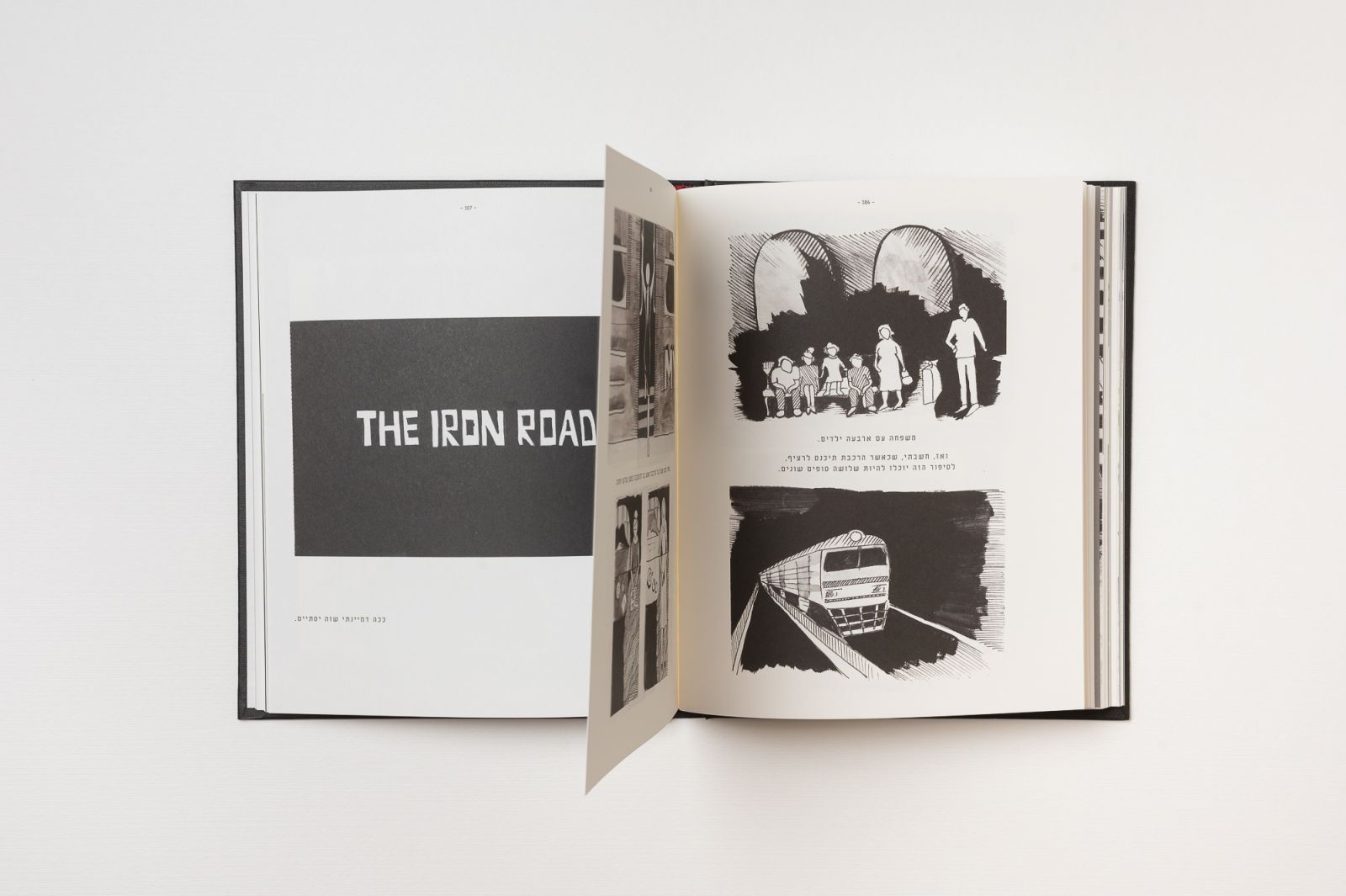

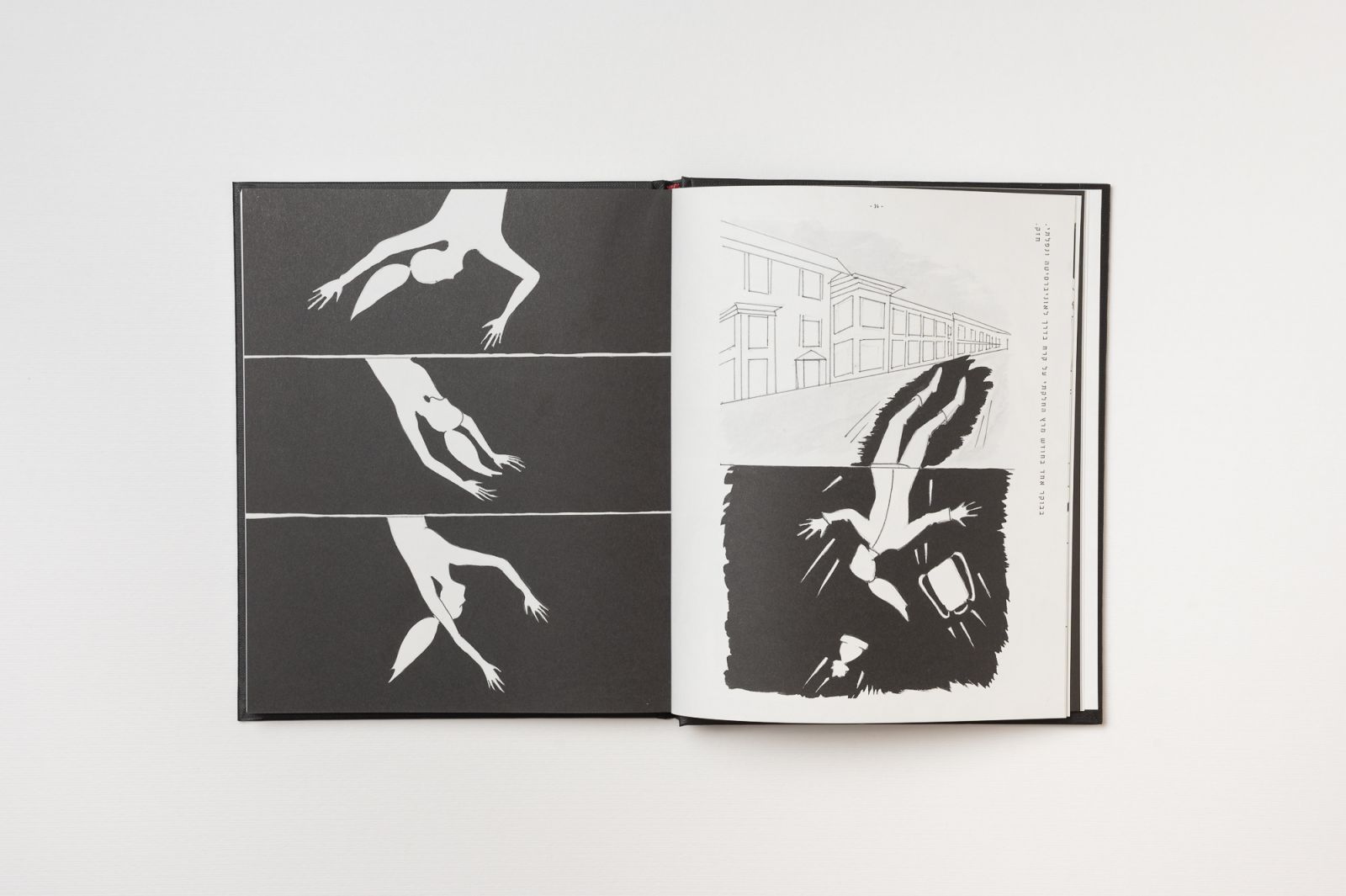

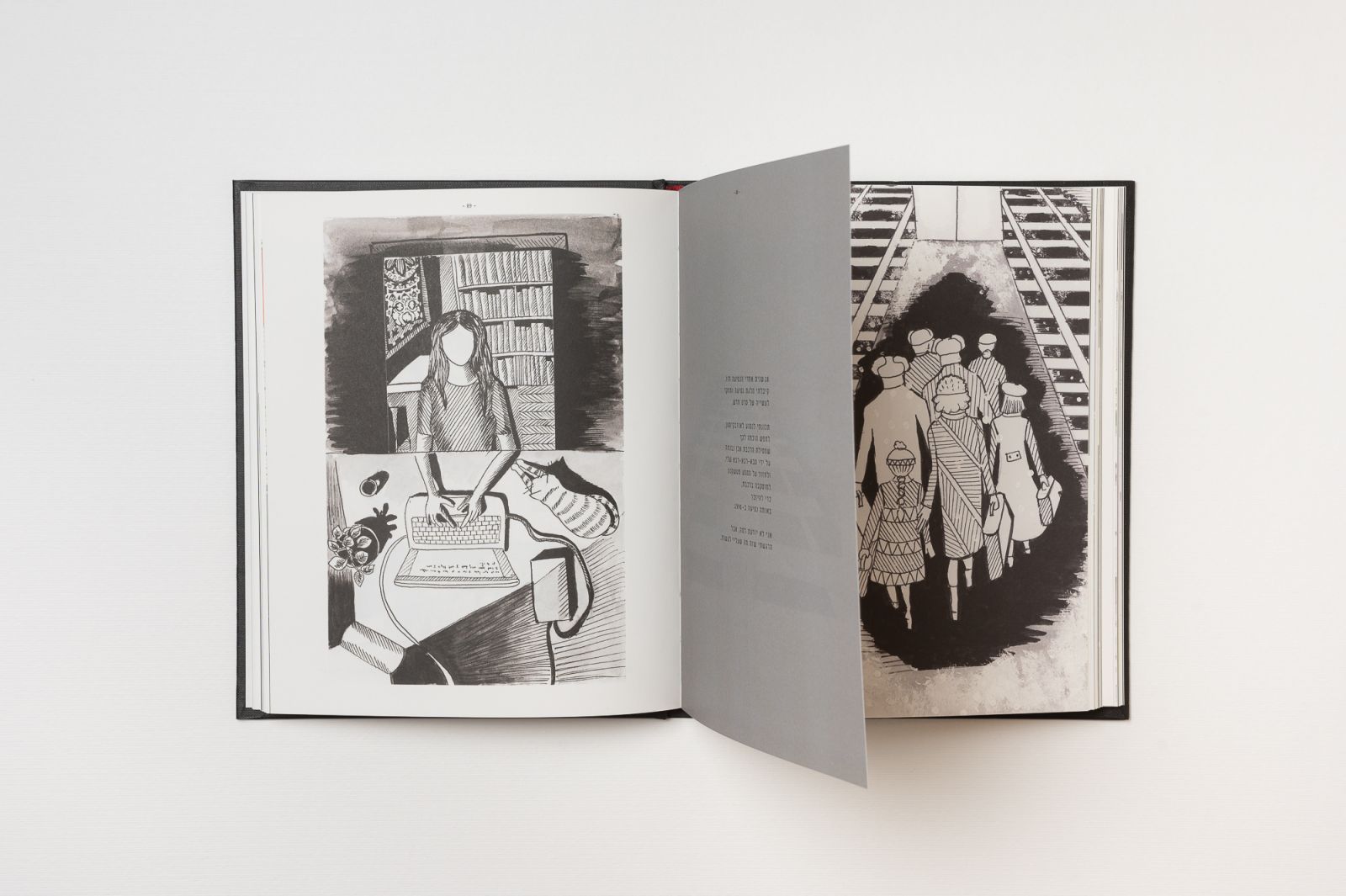

The book contains drawings and not photographs, so yes, there is some distance, an artistic move of the hand. That’s why I felt more comfortable bringing in the broader story, taking ownership of it. But I should also mention that the book actually started from only one scene, which appears here in the book exactly the same way as in the video; from the storyboard of the work The Iron Road [video, 2023] which is now on view at the Tel Aviv Museum. It started from a small glimpse, the fall and the free time that was created for me as a result, and the realization that it does me good to draw. I let the story unfold. It’s strange for me that people know a lot about me now, even the matter of the fall and the injury. Suddenly, when they talk about it in relation to the book, I understand the magnitude of the exposure.

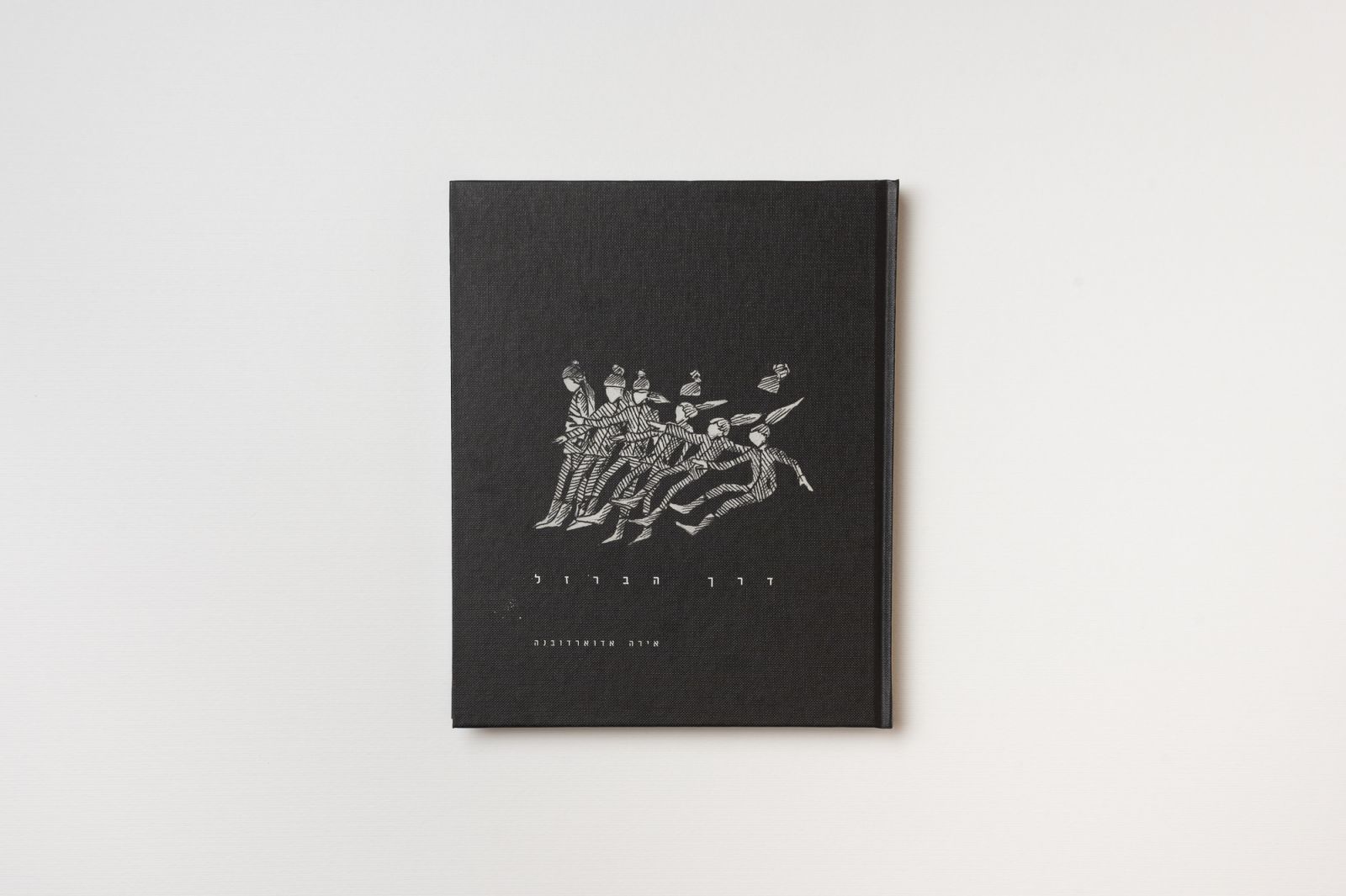

In a brave move, you chose to put the image of your fall on the cover of the book. Why?

It was the suggestion of Ayala Linav, the graphic designer. I didn’t want the fall on the cover. It’s a difficult moment in my life. It’s the most beautiful image in my eyes and from among the original drawings, I like it the most. My sister was the one who said to me, “This is not your fall, this is your getting up.” It’s the reverse. She changed the framing for me, and then I decided it would be on the cover. After the cover, it appears again as the first image in the book, which adds a poetic dimension to it.

Why did you choose to call the book The Iron Road?

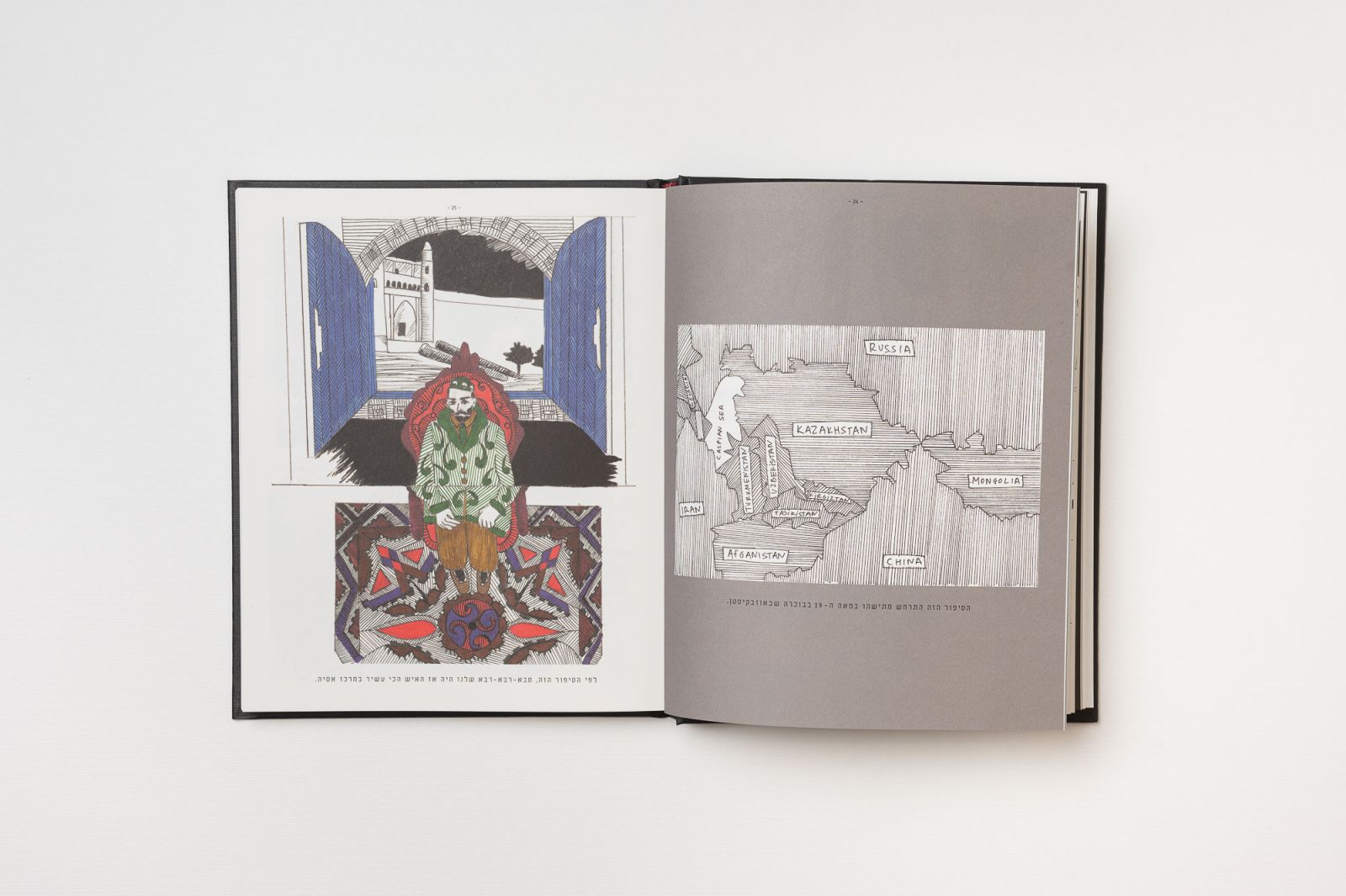

The beginning of the book was related to the video work of the same name. It’s a literal translation from Russian of railroad tracks. The translation sounds symbolic to me, because Uzbekistan lies on the route of the Silk Road along which the railway tracks also pass. Iron road corresponds with the concept of iron curtain, which produces an inversion: silk is soft and pleasant and iron is hard. I debated whether to give the book the same name as the video work, but I let it go because the book starts from the same scene as the video.

In the book, I found references to three of your video works: On Foreign Made Soles, The Library Room, and The Iron Road.

Yes, there are references to these three works. Recently, the rifle and the drawings were also added, which I didn’t anticipate would be a work, and in retrospect became the work 32,000 Rubles, which was presented in the exhibition NonFinito [the final exhibition of Artport’s artists-in-residence], last September.

This is your first work of art that is an object and not a video that is projected. Is the experience different?

A book has a different presence in the world. My biggest fear is what will happen if there is no electricity in the world? In that case, I won’t have a career. So it’s nice to know that there is a physical object that contains my work, and stands on its own. But it also causes anxiety: my concern for the original drawings. This is the first time that I have to think about how to preserve works so that they will not be damaged. And also, people can return to the book. People experience a video work in one moment, and it remains in their memory as a one-time thing, here they can return to it, look at it from close-up, and be with it.

Photo by: Tal Nissim.

What was the process of working on the book?

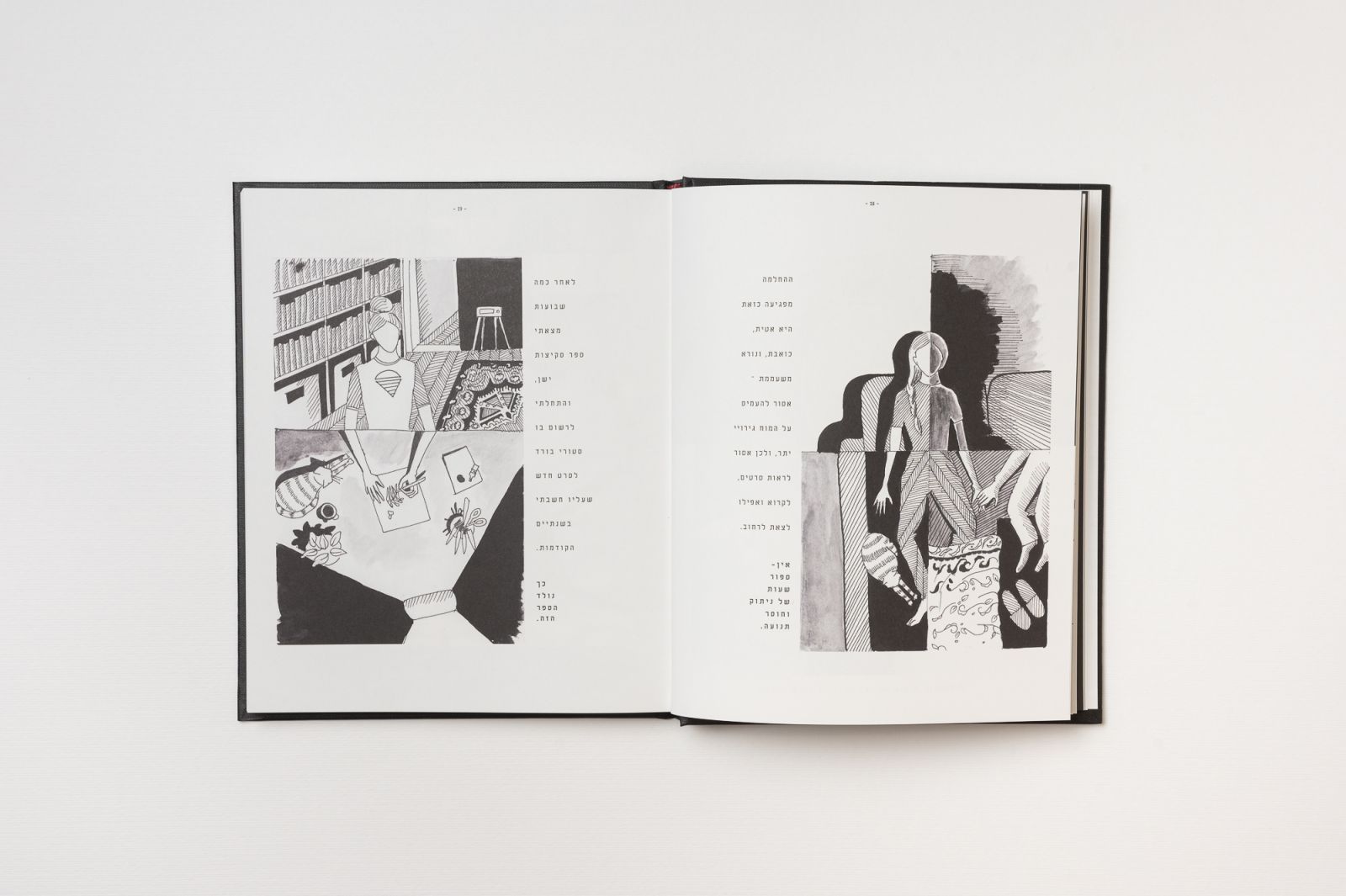

I never treated my drawings as an art object. For me, it was a sketchbook for the video work in the museum; it was always a tool to get to the video work. Because of the accident, I couldn’t work in front of screens, so I would go to the studio to draw. After I had a large amount of drawings, my partner Robi was the first to notice and tell me that I have a book here. Then I got the same feedback from other people I appreciate, curators and colleagues. It motivated me, even though I was not totally OK with it. I have never shown drawings. Drawing was always a technical thing.

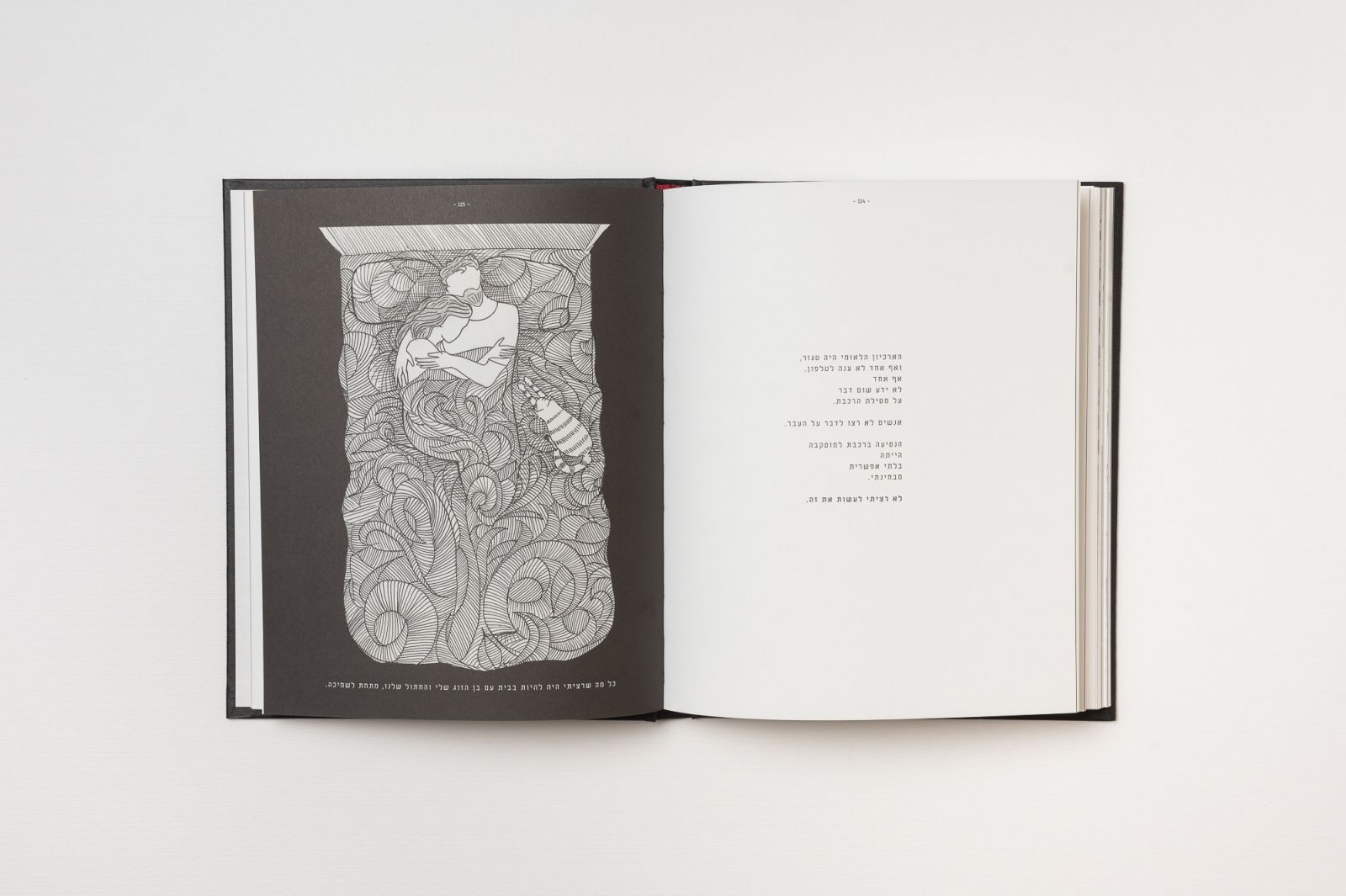

Because of the starting point and the initial intention, which was a storyboard, the process was very similar to the way I work on a video work. I think about a format and the story, write it, and start creating, drawing and delving into each scene. The creative time was also recovery time, my pace was slow, I had all the time in the world, I would make one sketch a day and go home. I always fantasized about being a painter, the kind of artist who goes to the studio every day, and works slowly. My usual way of working includes hours in front of a computer in production, three days of intensive filming, and then again hours in front of a computer editing. In retrospect, I had not intended to fulfill that dream under these circumstances, but I enjoyed it, it was meditative and relaxing.

After meetings with several publishers, I decided to publish the book independently, I wanted full control over the process. I worked with the designer Ayala Linav and the language editor Avri Harling and many other good people who helped and advised me about things I had no idea about. I wanted to keep the format relatively small and intimate, a sketchbook that can fit in any bag.

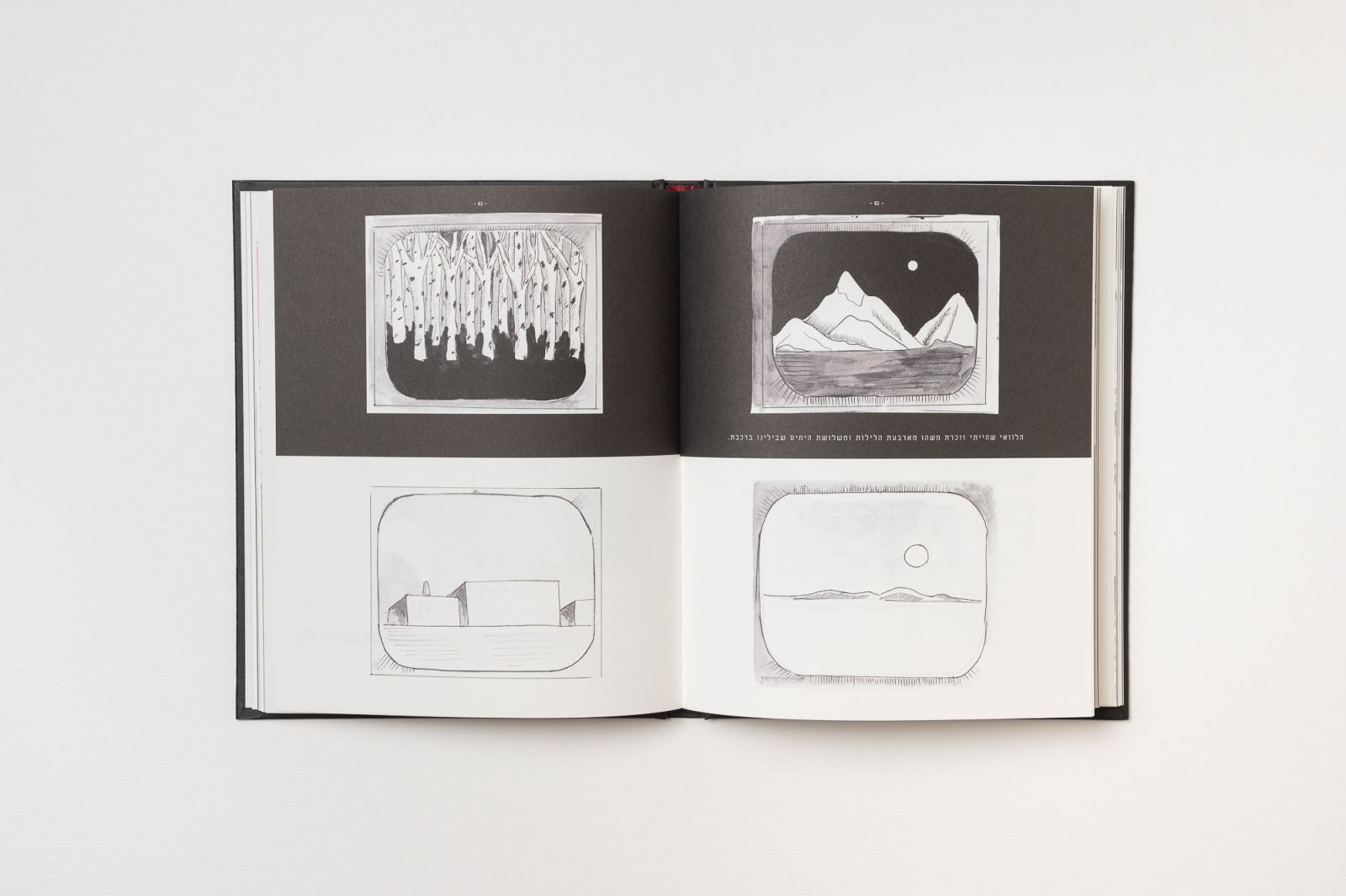

The graphic design was very significant, I am very happy about the joint work with Ayala. She understood how I drew and chose to correspond with it. She divided the book into a black part and a white part; the gray color marks the beginning of each chapter which is an entry into another time: Boston time, Uzbekistan time, a new moment.

The stories in the book, as in your works, challenge historical truth and memory. Although you go deeper and perform repetitive actions that make viewers experience and process the story with you over and over again, you also challenge the ingrained narrative and the degree of its authenticity. Why is this action so important to you?

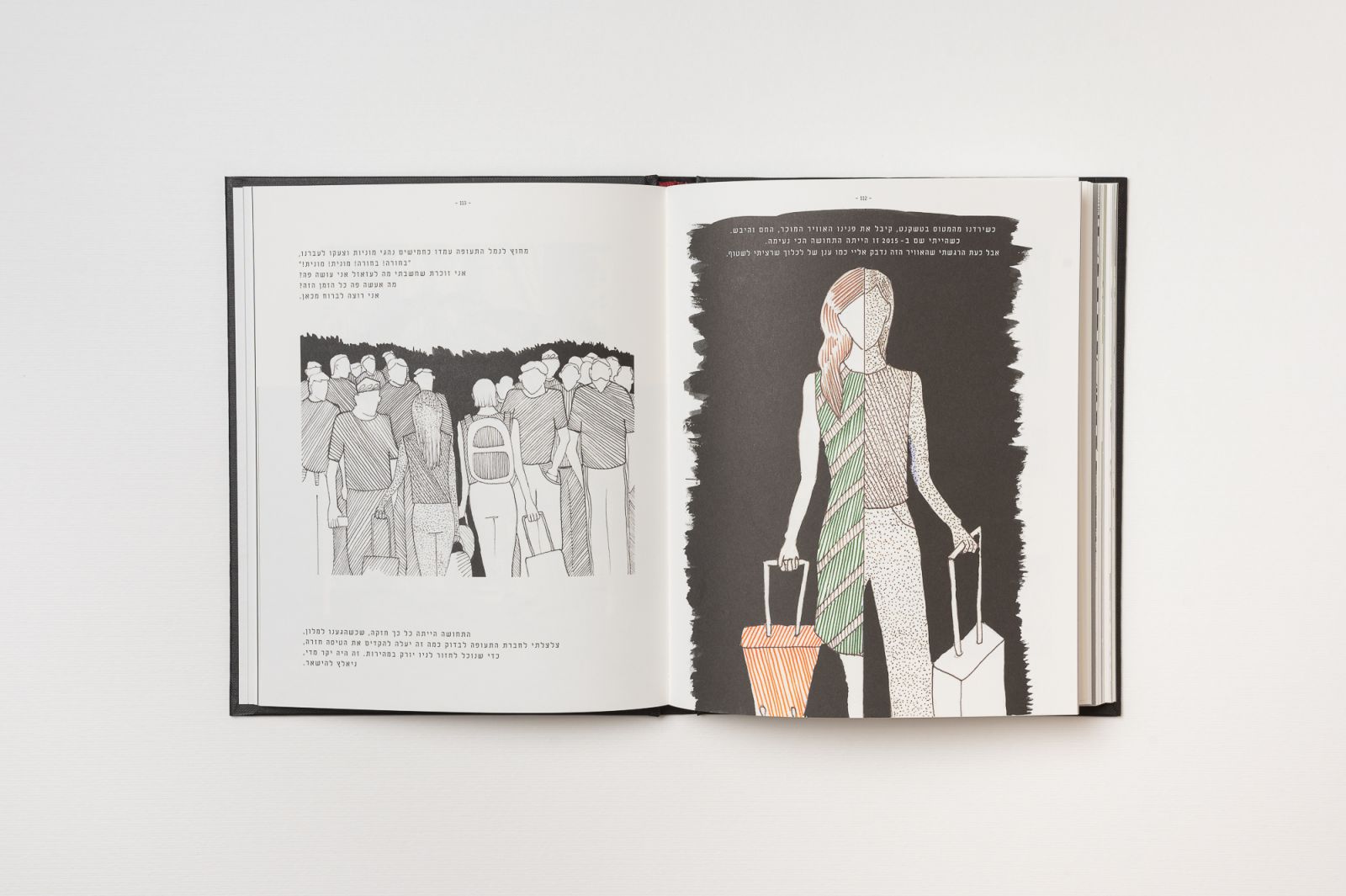

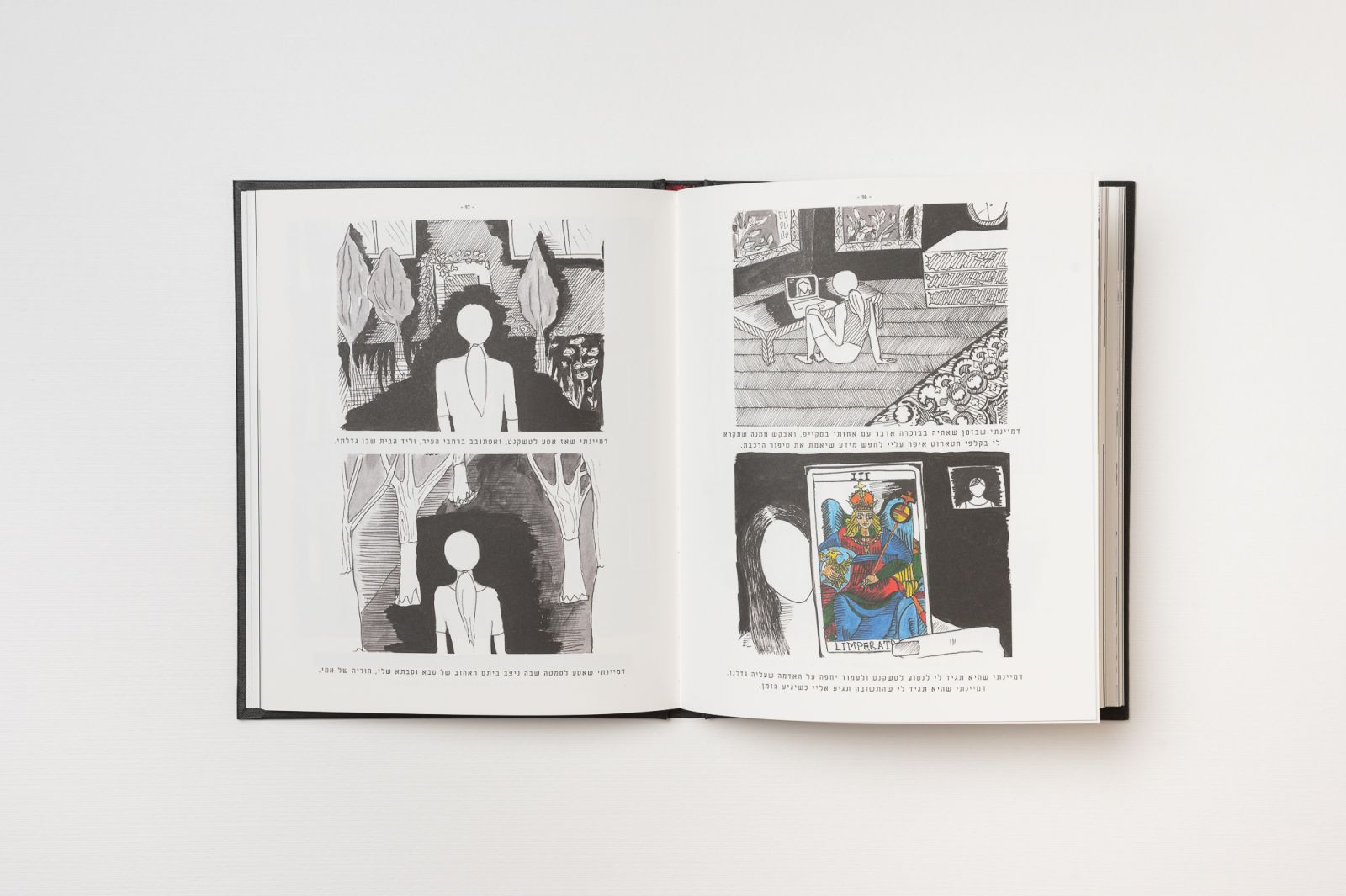

I raise a question not only about personal memory, but also about collective memory which, in the end, is written as the history of a country or a people, and is tested through my own personal and collective memory. In the book and in the video work there is the story about the grandmother who says goodbye to us at a train station and reaches out her arms. I remembered the moment like this, and she was left behind. Before filming, I recounted the memory to my mother, and she said that there was no grandmother there. It was important for me to include this discovery in the book. I and all of us experience memory this way, we don’t really know if what we remember is real, or if an alternative was created, due to a trauma for example. I dig around in this in order to reach a certain kind of truth and without success, perhaps in order to reach the understanding that the memory is the truth. There was a woman standing there who reached out, I don’t know who she was, but I thought she was my grandmother and I experienced separation from her, even though she wasn’t there.

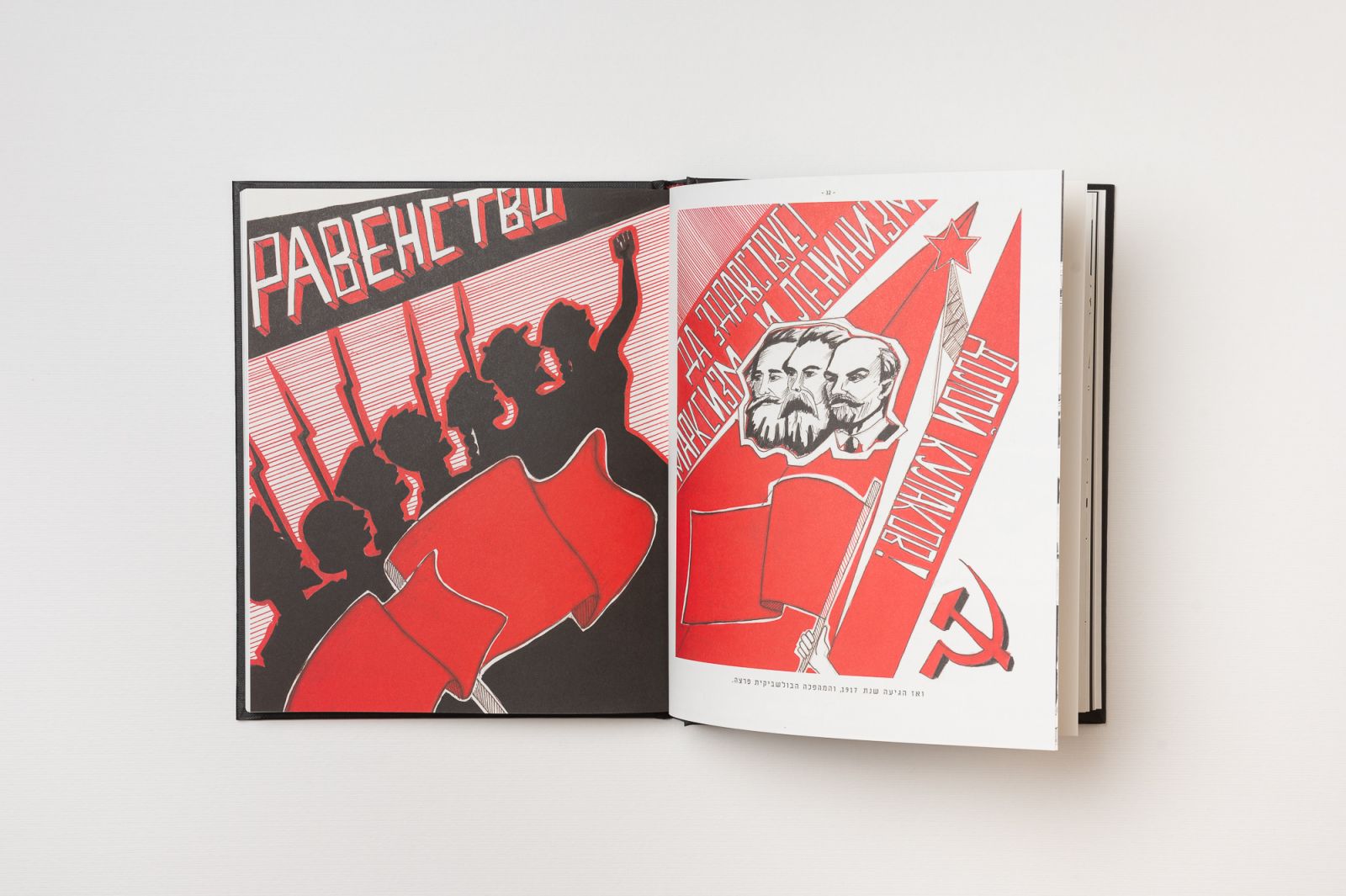

I grew up in the Soviet Union which was communist. The West I had learned about was different from what I found in Israel. In the Soviet Union they taught that they had defeated the Nazis on their own. When I came to Israel I argued with people who claimed that the Americans had won. It drove me crazy. It made me ask how history is taught, who teaches and writes it. The documentation of memory is a way to open this dialogue, even our most painful memories are not necessarily what happened. Our own experience is the reality.

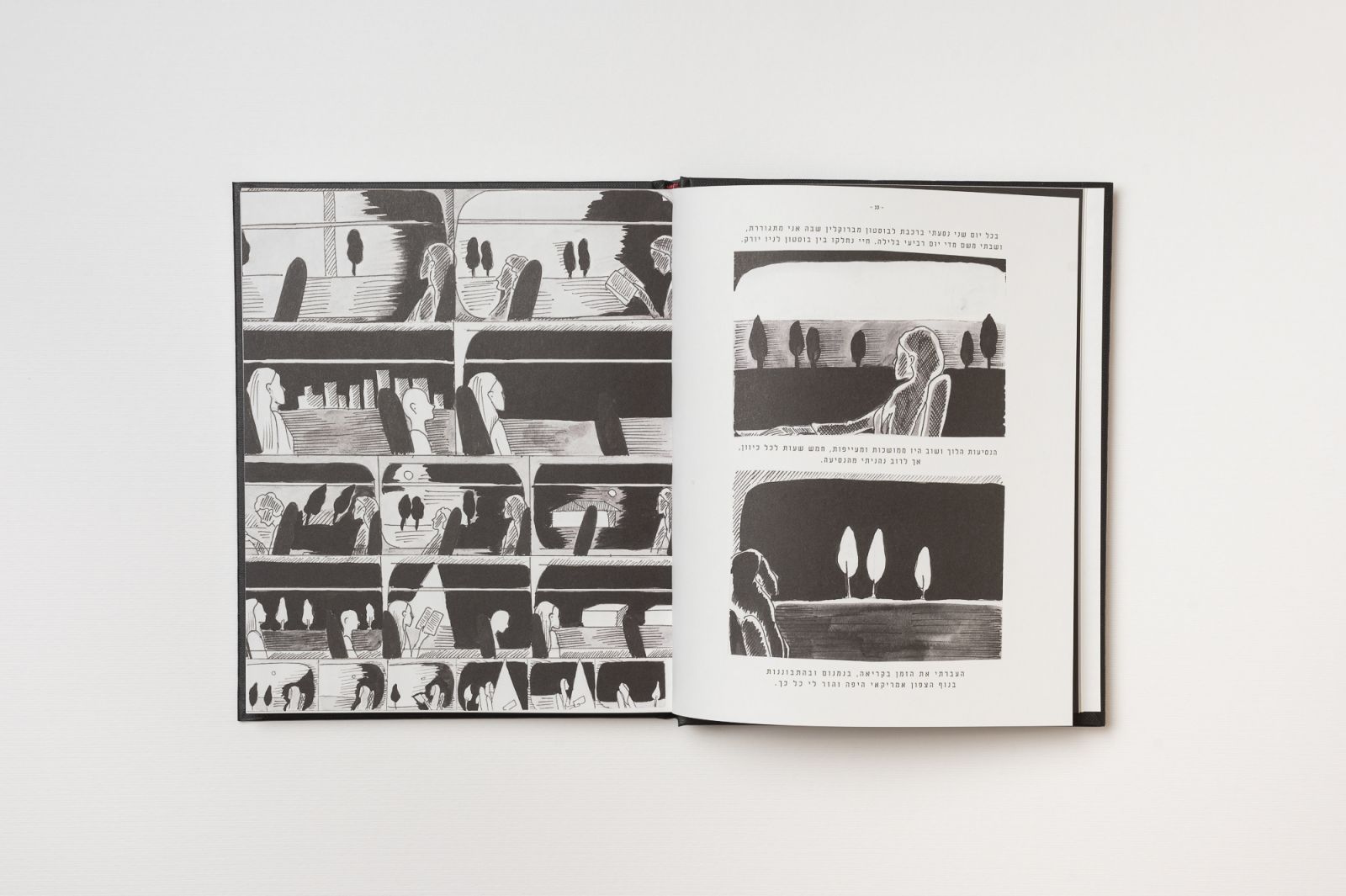

It appears that the train is your transitional object. It is the means of transportation that reverberates in your stories. The train helps you to move and divide your life between places, between Uzbekistan and Moscow, between Boston and New York. It tells about the family history that is passed down from generation to generation, about your grandfather who built the railroad. It also tells about an imagined future for a new job that did not materialize. It seems impossible to ignore the preoccupation with identity and place, displacement and migration that accompanies and is performed by the train. The view from the train window is a motif that repeats, it fits the frames of the video, the frame in a comic book, but it is also a way of sitting and watching the movie that passes before your eyes. It’s like you are not part of it.

The story about the railroad tracks that my great-great grandfather built is a defining moment, etched in the small collective memory of the family. He was the trigger for the video work The Iron Road from which, as mentioned, the book was also born. When I photographed this work, my sister said: This is the hardest night of our lives. On the one hand, it’s really something difficult that’s burned into my memory.

On the other hand, there is all the poetics of the train. The journey that lasts several days, the compartments and the restaurant car, sleeping with strangers, everyone brings their own food, a connection forms from sitting together and playing the guitar. In Soviet cinema there is a genre of train scenes. There is all this cultural romance, compared to what really happens on the train. For me, it was a space of terror. My father bought the whole car because there were stories about pogroms against the Jews, shooting into cars in order to steal their property. With us in the car were three cousins who came as guards, the whole car was empty, complete anxiety. It was a very intense moment, after which came adapting to Israel, where life became very intense, and that moment was erased. When I heard that maybe the great-great grandfather built the railroad, it was so cinematic that I couldn’t ignore it. Immediately there are two stories of the train here, the legend and our story.

Later, the story of the fall on the train in Boston came out of an awareness of this train corresponding with that train, foreshadowing that a more significant train is yet to come. As you suggested, it is a doubly transitional object: it is a transitional space, a temporary home, a room that is supposed to provide you with a sense of comfort for a time. In me, it evokes attraction and anxiety at the same time.

Two things stand out in the book, the fact that the characters have no facial features and what they feel is only expressed in writing, and the fact that the book is mostly in black and white with rare flashes of color in one of the drawings. Can you tell me about these choices?

There is something vague about facial features in memory. I always feel that we don’t remember faces of people from the past who were important to us. This corresponds with the sense of the question about memory. The only faces that appear in the book are of people I didn’t know, that I don’t need to remember. They are almost mythological figures, like my great-great-grandfather, or Engel, Marx and Lenin.

I was afraid of over illustration of internal emotion because the book is very emotional for me. When I read reviews of the book later that wrote that it was difficult to find emotion in it, I was surprised. For me, I feel that it is very charged, and I wanted to distance it, not turn it into a melodrama. Because it started as a storyboard, in which I work without color, it was important for me to keep the format that corresponds with cinema.

Do you think you will do another artist’s book?

In preparation for the Artport artist’s book fair, I made another book that is a one-off and was displayed in the White Gloves room. This is a research book of this book, it has lots of photographs, sketches for thought, visual attempts for a book and video work. I love these materials, and I decided to combine them into another book. It contains many of the photographs from the trip to Tashkent and the train, and some small sketches of scenes that did not make it into the book. This is a book that is behind the scenes of this book, which is behind the scenes of the video work. I have thoughts of making the book into an animated film, in the field of narrative cinema. There were several production companies who approached me and I’m thinking about it.

Who did you dedicate the book to and why?

To my son, Alexander. I finished the book a week before I gave birth, it was the peak of the corona virus and I was in New York. I was cut off from family who couldn’t come for the birth. The feeling of corona in New York was apocalyptic, the streets were empty and it was a scary time. I wanted to dedicate it to him, so that he would have a have a document about that time.

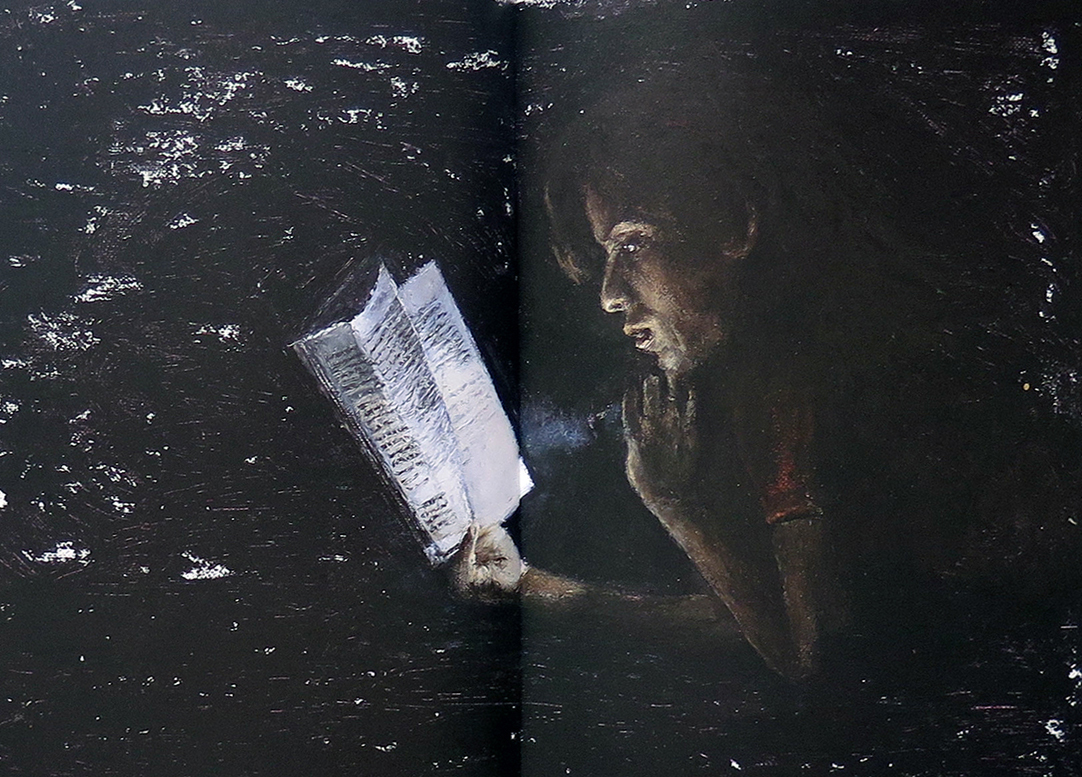

Is there an artist’s book that guides you or that you particularly like?

I have an amazing library of artist’s books back in New York. There is an artist named Constance DeJong who was a teacher of mine at Hunter, who is a spoken word performance artist. Her book Speakchamber is actually a text, but also an artist’s book. It’s an amazing experience of reading images that she brings in the form of writing. It’s like seeing a performance in a book.

What book should we add next to our library?

Sahar by Haitham Haddad and Anat Martkovitz.

"It started from a small glimpse, the fall and the free time that was created for me as a result, and the realization that it does me good to draw. I let the story unfold. It’s strange for me that people know a lot about me now, even the matter of the fall and the injury. Suddenly, when they talk about it in relation to the book, I understand the magnitude of the exposure."

"When I heard that maybe the great-great grandfather built the railroad, it was so cinematic that I couldn’t ignore it. Immediately there are two stories of the train here, the legend and our story."